Archive for April, 2019

April 21st, 2019 by dave dorsey

I was pleased and surprised when I got the notice that the Butler Institute of American Art wanted my painting of taffy for its Midyear exhibition, since other work had been rejected this year by our local museum and another regional gallery. After a decade of selling my work and showing it in juried exhibitions, it was still a game of percentages, entering these events. This year it might be only the two small museums that showed my work—Arnot and Butler—mostly because I haven’t had the time to finish enough work to enter other shows. Last year, I’d vowed not to enter anything larger than 24” in at least one dimension, and if possible enter nothing larger than that in any dimension. The difference in cost, and the amount of hassle that goes into the whole physical process of getting a painting to and from a show, is dramatic, when you exceed a certain size. But I had nothing else to enter, having submitted smaller paintings to other shows. So in the week I was home in Pittsford, I had to build a new crate, the largest yet, and figure out how to get it to Youngstown, Ohio and back.

I was pleased and surprised when I got the notice that the Butler Institute of American Art wanted my painting of taffy for its Midyear exhibition, since other work had been rejected this year by our local museum and another regional gallery. After a decade of selling my work and showing it in juried exhibitions, it was still a game of percentages, entering these events. This year it might be only the two small museums that showed my work—Arnot and Butler—mostly because I haven’t had the time to finish enough work to enter other shows. Last year, I’d vowed not to enter anything larger than 24” in at least one dimension, and if possible enter nothing larger than that in any dimension. The difference in cost, and the amount of hassle that goes into the whole physical process of getting a painting to and from a show, is dramatic, when you exceed a certain size. But I had nothing else to enter, having submitted smaller paintings to other shows. So in the week I was home in Pittsford, I had to build a new crate, the largest yet, and figure out how to get it to Youngstown, Ohio and back.

The only reliable way to do this was either to drive it there myself—about ten hours of a round trip on the road to deliver it and another ten to pick it up after the show, which I had done for the last show I was in at Butler—or ship it through the UPS Store. I had tried both Fed Ex and UPS before, signing up for accounts, but in every case I got lost in the obstacle course of being transferred to other people, or put on hold, or told to do things that weren’t available to me in the online forms. This time was no exception. The shipping companies aren’t terribly interested in a non-commercial shipper who wants to do things—like print out a return label—that only retail companies usually need to do. Getting that return label pre-paid and printed and inserted into the crate was the stumbling block. I called and the UPS help desk and they told me I had to actually create a permanent account with them, and so I did. They supplied me with my own account number, but it changed nothing in the form. Still no option to print a return label. Which is when they put me on hold for a transfer—and no one picked up. So I surrendered to defeat again and decided I would have to lug the four-feet by four-feet crate to the UPS Store, all sixty pounds of it, rather than have them pick it up.

Before 8 a.m. I drove to Home Depot and got a 4′ x 8′ sheet of quarter-inch plywood sheathing— thin and flexible and lightweight. It’s more delicate than typical plywood and pretty easily punctured if you were to drop the crate onto something like a giant paper spike, which UPS once apparently tried to do with a previous shipment, luckily without damaging the painting inside. I had a friendly, helpful worker cut this sheathing into two identical squares and then slice the six-inch boards I would use for the sides of the crate into a pair of four-feet long planks and another pair of slightly shorter ones. I’d create the box out of them and then screw the sheathing to each side, using drywall screws. I’d done this many times, so I was finished by noon. Inside the crate, I attached a convoluted foam mattress top to the sheaths as cushion for the painting, and constructed an inner “lid” out of foam core to slip over the front of the canvas, so the lining wouldn’t press against the canvas inside the crate. Continue reading ‘A long goodbye’

April 18th, 2019 by dave dorsey

When I was a boy, I used to take a toy, whether or not it was meant to represent something aeronautically sound, and I would hold it out in front of me and “fly” it above the sofa mountains of our living room or, outside, over the terrain in our East St. Louis yard: a stone wall, peonies and day lilies, an actual manual pump (like the ones in Westerns) drawing air from an unproductive well, apple trees and woods. The scale of everything would be altered by whatever I was holding in my hand, an airplane, a Superman, or a scuba diver. I wanted to be a scuba diver more than anything in grade school. (Or a sardonic gambler with a six-shooter on my hip in a frontier Nebraska saloon.) A little molded plastic figure of a diver, lime green or blue, would swim over vast underwater canyons carpeted with bluegrass. I was the invisible giant holding him up: a giant or a god. The world was my diorama. Everything became more interesting.

I get the same feeling looking at a close-up detail I shot a few months ago at The Getty of a masterful Chardin still life I’d never seen before. Up close, the objects on Chardin’s mantle look massive, like magical alien minarets and a flat-topped stadium, a terrain out of Gulliver’s Travels. It’s a strange city built with things from his kitchen. Bachelard would have been nudged by this scene into a reverie, another unique poetic measure of space, if he imagined everything in the picture a thousand times larger than its actual size. (I suppose you have to leave out the fish.) It becomes like one of those clockwork models of cities rising up out of the earth during the title sequence of Game of Thrones. This effect is partly what draws me to enlarged images of ordinary objects—making them massively larger on canvas than they are in my daily, disenchanted world—to bring out their formal resonance with so many other things with similar shapes and tones. In a way, I think this is related to what Braque meant in his notebooks about the centrality of transformation in painting, the alchemy that takes an ordinary interior space, full of utterly familiar things, and turns it into a painting’s dream. His transformations were more radical, obviously, but Chardin is just as concerned with the feel of the paint itself and the tactile quality of what’s seen–making you aware of the medium that invites you into its world, the same as yours, but cooler, fresher, more alive.

I get the same feeling looking at a close-up detail I shot a few months ago at The Getty of a masterful Chardin still life I’d never seen before. Up close, the objects on Chardin’s mantle look massive, like magical alien minarets and a flat-topped stadium, a terrain out of Gulliver’s Travels. It’s a strange city built with things from his kitchen. Bachelard would have been nudged by this scene into a reverie, another unique poetic measure of space, if he imagined everything in the picture a thousand times larger than its actual size. (I suppose you have to leave out the fish.) It becomes like one of those clockwork models of cities rising up out of the earth during the title sequence of Game of Thrones. This effect is partly what draws me to enlarged images of ordinary objects—making them massively larger on canvas than they are in my daily, disenchanted world—to bring out their formal resonance with so many other things with similar shapes and tones. In a way, I think this is related to what Braque meant in his notebooks about the centrality of transformation in painting, the alchemy that takes an ordinary interior space, full of utterly familiar things, and turns it into a painting’s dream. His transformations were more radical, obviously, but Chardin is just as concerned with the feel of the paint itself and the tactile quality of what’s seen–making you aware of the medium that invites you into its world, the same as yours, but cooler, fresher, more alive.

I was familiar with many of the objects in this picture from his other paintings, because he kept returning to these old inanimate friends again and again, as still life painters like to do: shallots, garlic, a couple gougeres (they look like cream puffs), several ceramic bowls with covers secured by lengths of twine, and a silver dish designed to hold two glass-and-silver cruets for oil and vinegar. Freshly-caught mackerel in the background are the wild card. Chardin did this at least a couple times—showing you fish and game ready for cooking. But he indicates the shining white underside of the fish with impasto streaks of paint uncharacteristic of his usually subtle handling. In a photograph, it looks right. In front of the actual painting, it distracted me and felt like the part of an overexposed photograph where highlights wash out into too much white. In the end, though, the problematic fish and the way he painted them make the painting even more interesting.

Continue reading ‘Chardin’s dreaming’

April 8th, 2019 by dave dorsey

Face Painting, Jonas Wood (2014). Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Bill Santelli sent me this interview, which is a good read. Jonas Wood makes Hockney-esque paintings that look like graphic art, colorful in unpredictable and interesting ways, and dense with detail. They feel immediate and carefully observed but executed with almost childlike simplicity. I love the embrace of flatness because it forces him to put so much of his feeling into the color and his color can be extremely good (but sometimes not all that interesting.) What you see is what you get and that has to be part of his appeal, the ordinary quality of the experience he conveys. It’s funny to hear Wood talking about his staff and his office. Who does he think is going to hire a staff after reading this? The only staff I could imagine wanting or needing is Gmail with a good spam filter and auto-reply as my receptionist. Which he would applaud, if it worked to manage the tsunami of demand I anticipate any day now. It’s sort of his point: detach yourself from all pressures other than the work and get it done, but that’s easier to say when you are selling work for $2 million in an auction. There’s a no-nonsense fearless voice here, but it’s speaking back towards us in a foreign tongue he picked up in this other dimension of big art world success where nothing is commensurate with the way all but one percent of one percent of artists live. All of this reminds me of France before the storming of the Bastille. Where did Fragonard go after the revolution? I think he just dematerialized. Or maybe he finally hired a staff. But it doesn’t seem we are at that point, income inequality notwithstanding. We’re facing something different. Economically, Wood is among the elite of the elite. This world the rest of us live in, the world nearly everyone else lives in, can’t imagine hiring a staff. But who doesn’t envy Wood’s ability to just do what he loves doing and, voila, the money and attention flows? Reading his comments feels like watching the Kardashians have breakfast while they talk about how you need to become an Instagram star as practice for your reality TV show. Working hard isn’t what gets these results. Most of the factors that make Wood’s work so lucrative are beyond anyone’s control–and if art schools teach anything about the market it should be that you aren’t going to face his choices. It happens to an infinitesimally small number of people who get beamed up to this rarified world, and then have to find a way to shelter in place from the abundance of their new planet, the way Wood does, in order to keep working. Hard work is a given, but it isn’t enough. Van Gogh ramped up to a painting a day, more or less, near the end. Nobody has ever worked harder. It got him something far preferable to sales.

Some good advice here, with the intro from art.net:

Jonas Wood is not shy. He won’t hold back, takes aim when he fires, and doesn’t seem concerned about ruffling anyone’s feathers. He’s also busy—very, very busy—and seems to have a lot on his mind.

When artnet News spoke with the artist earlier this month, he was preparing for the first institutional survey of his work at the Dallas Museum of Art, which opened last week. The show is a real boon; although Wood has earned a solid reputation for his lush interiors, tender portraits, and vibrant still lifes, which he has shown in dozens of commercial gallery exhibitions, museum support has largely eluded him until now. Not that he has much time to bask in his success. In April, Gagosian will present new works by the artist in New York, which means he has to quickly shift gears and look ahead.

From Wood’s answers to artnet’s questions:

I think it happens to be that I have a broad audience right now. Maybe that’s not always the case, but the reason I paint is not for those people. I think it’s for my own mental health and for my own sort of goals as a painter, but I’m aware of the viewer.

I worked with Laura Owens. And I got this really good advice—and from other people too—which was just, if you want to separate yourself from the noise, you’ve got to create some distance. Another thing was just saving my own work and not being so greedy, and being aware that, okay, $5,000 now is $5,000 now. If I sell three more paintings, yes, I’ll get a little bit more money, but it’s not like life-changing money. Maybe I should start holding onto things for myself and not selling everything. I mean, the dealers are going to hate hearing this, but maybe they won’t. Maybe it’s good because they want an empowered artist. But they would offer to give me money to buy stretchers and buy stuff for my studio, and I didn’t really want them to buy stuff for me because I didn’t want them to know how many paintings I was making.

I was painting for me, and I knew that I didn’t want to paint for the collector audience. I wanted to paint for me.

So establishing that was really important for me because I was able to keep my practice open. I didn’t want to be pigeonholed right away. I showed a lot of different kinds of work, and I didn’t really cut myself off and be like, “He’s the tennis court painter.” Or, “He’s the sports portrait painter,” or, “He’s the guy who makes the still life.” I guess I’m kind of all of those things, which is better than just being one of those things.

Well, when I was at school in 2002 at the University of Washington, my goal was to teach at a liberal arts school, have a studio on campus, have the summers off. That was probably my ideal.

Man, it’s fucking tough because people say crazy shit about your work. You have to be super thick-skinned, and it’s hard. That’s a big part of it. I would say that you just have to take all that energy back to your studio and try to be critical in your own way and just take that criticism. Just say, “Okay, yeah, I’m going to keep looking because maybe these people have a point.”

But that type of shit is tough. Dealers saying crazy shit, your friends saying crazy shit, collectors saying crazy shit, having a show where you don’t sell a bunch of stuff. That shit is tough.

April 5th, 2019 by dave dorsey

Iris Murdoch

I’ve just reread Iris Murdoch’s The Sovereignty of the Good, in reaction to my rereading of Dave Hickey’s The Invisible Dragon, in an effort to see the contrast between their ideas about beauty. Hickey speaks about beauty and desire. Murdoch about beauty and love. One might think they are speaking the same language, Hickey at a very high rate of speed, full of rebellious spunk, and Murdoch deliberately, cautiously and in the dry language of a professional philosopher. They were both pushing back against a tide of thinking and theorizing, in their time, about what it means to be a responsible social human being. There is some commonality. It would seem Hickey would have been very uncomfortable with Murdoch’s wisdom. They arrive at what sound like very different conclusions, yet I’m wondering if Hickey might have appreciated Murdoch’s embrace of Greek philosophy a little more than he lets on in his own book. On the evidence, his view of beauty seems entirely utilitarian compared to hers, but his assertion that artists need to do beautiful work in familiarity with a tradition of past beauty that has some kinship with Murdoch’s concept of attention.

She starts off in the weeds of shop talk, fending off one academic philosopher after another, trying to somehow save the idea of individual subjective consciousness against all the 20th century efforts to render human beings merely an agglomeration of genetic/cellular activity–or an isolated will, an abstract freedom of choice, completely detached from any governing reality external to the individual will. (The latter, existentialist view, has certainly receded since she wrote her book.) In rereading the book, at first, I was annoyed and puzzled by how dense her thinking gets, right out of the gate, as she fends off the other thinkers–analytic and existentialist both–who want to dismiss the idea of what used to be called the human soul, a consciousness that isn’t simply the epiphenomenon of bodily activity. She tentatively asserts subjective consciousness as the only way to describe the actual experience of being alive and human–an inner life apart from actual behavior that proves to others it exists–in order to build her philosophy of Goodness. Everything good in human behavior for her depends on a lone individual’s effortful attention to other people and things external to the self and she needs that inner life, that inner struggle of attention, which goes on invisibly from moment to moment (essentially a sort of continuous, daily discipline of contemplation) for her view of moral goodness to make sense. (Though she probably would have been disheartened by the current ubiquity of mindfulness meditation, complete with helpful apps on your phone, her thinking isn’t all that far from the moral dimension of mindfulness.)

For now, here’s a long series of excerpts from throughout her book. Any painter, including abstract painters, will recognize how much this describes the act of painting, how little depends on personal choice and how much relies on obedience to the requirements of a given picture, even though her focus is on moral behavior. She sees very little space between moral attention and creative attention:

But if we consider what the work of attention is like, how continuously it goes on, and how imperceptibly it builds up structures of value around about us, we shall not be surprised that at crucial moments of choice most of the business of choosing is already over. This does not imply that we are not free, certainly not. But it implies that the exercise of our freedom is a small piecemeal business which goes on all the time and not a grandiose leaping about unimpeded at important moments. The moral life, on this view, is something that goes on continually, not something that is switched off in between the occurrence of explicit moral choices. What happens in between such choices is indeed what is crucial.

If I attend properly I will have no choices, and this is the ultimate condition to be aimed at. The ideal situation . . . is . . . to be represented as a kind of ‘necessity’. This is something of which saints speak and which any artist will readily understand. The idea of a patient, loving regard, directed upon a person, a thing, a situation, presents the will not as unimpeded movement but as something much more like ‘obedience.’

This is what Simone Weil means when she said ‘will is obedience not resolution.’ As moral agents we have to try to see justly, to overcome prejudice, to avoid temptation, to control and curb imagination, to direct reflection.

One of the great merits of moral psychology which I am proposing is that it does not contrast art and morals, but shows them to be two aspects of a single struggle.

In one of those important movements of return from philosophical theory to simple things we know about great art and about the moral insight which it contains and the moral achievement which it represents. Goodness and beauty are not to be contrasted, but are largely a part of the same structure. Plato, who tells us that beauty is the only spiritual thing which we love immediately by nature, treats the beautiful as an introductory section of the good. So that aesthetic situations are not so much analogies of morals as cases of morals. Virtue is au fond the same in the artist as in the good man in that it is a selfless attention to nature: something which is easy to name but very hard to achieve. Artists who have reflected have frequently given expression to this idea. (For instance Rilke praising Cezanne speaks of a ‘consuming love in anonymous work.’) Continue reading ‘Magnetic and inexhaustible reality’

April 2nd, 2019 by dave dorsey

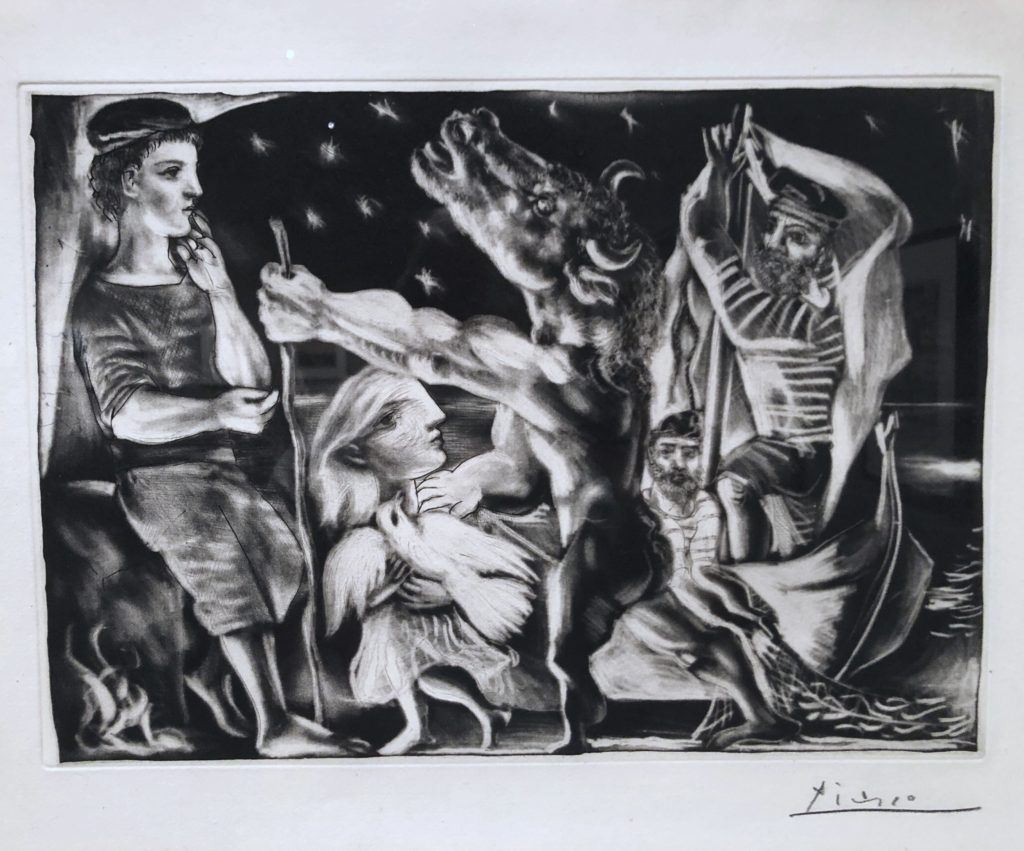

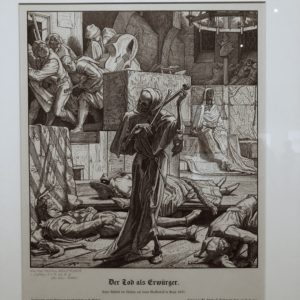

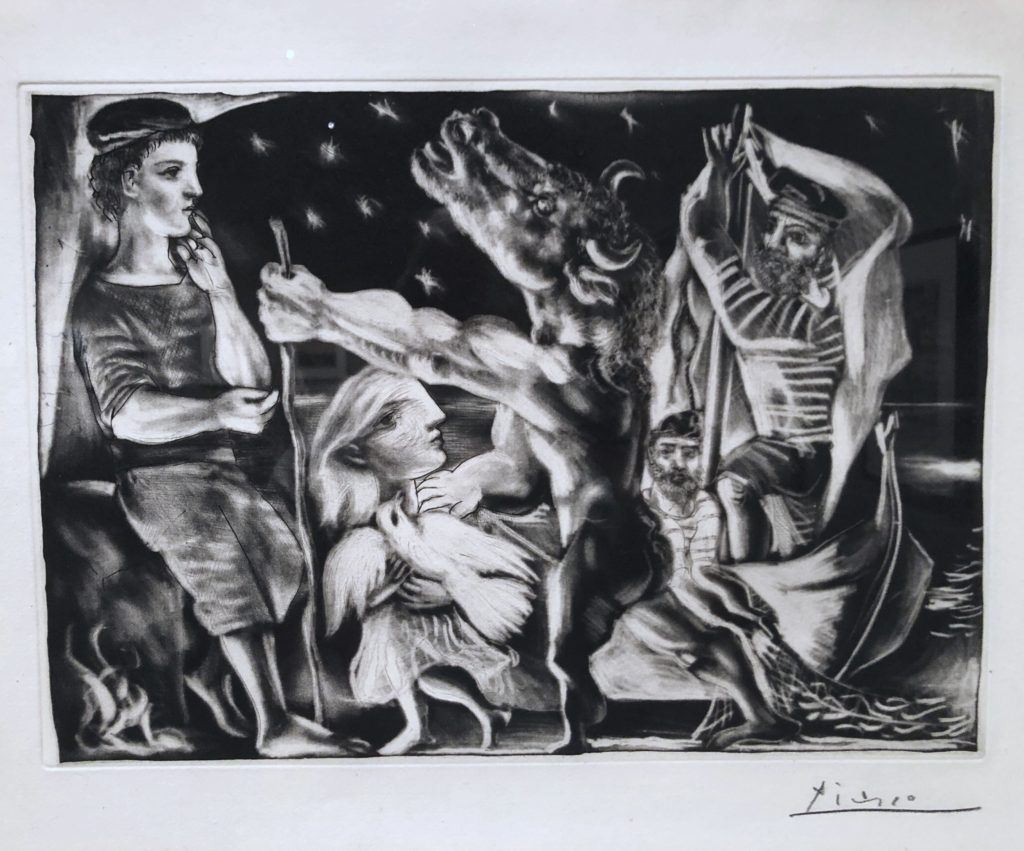

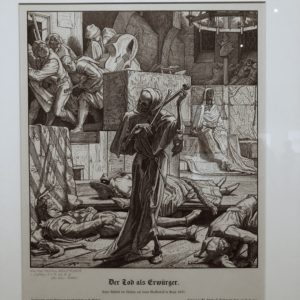

Pablo Picasso, Blind Minotaur Guided by a Girl at Night, burnished aquatint

I’ve been surprised that the exhibit that has occupied my attention the most since my last visit to LACMA was Fantasies and Fairy Tales. It was a small, quirky collection of prints from around the year 1900. The aim of the exhibit was to show how, within this tight, curatorial window of qualifications (prints mostly within a narrow, fin-de-siecle range of dates), a selection of work could suggest  incorporeal states of mind or spirit, as well as hint at transcendence. The show was beautiful and eerie, dreamlike and occasionally chilling. There was a slightly morbid strain in the imagery on view, but it was tempered with stylistic wit in the work itself and the playfulness of the curation. Charles Addams might have brought an Edwardian folding chair to this one, the better to take it all in. David Hockney etched a simple rear view of the prince nudging his horse up to Rapunzel’s dangling locks. In Death the Strangler, Alfred Rethel engraved an image of a skeleton in a hooded monk’s habit pretending to play a fiddle with a pair of leg bones as people cowered around him. Max Klinger’s aquatint, Pursued Centaur, depicted three seemingly naked hunters chasing a centaur through long grass—right after the centaur has loosed an arrow backward into the leading horse’s neck. It shows you the moment when the hunters became the hunted. It’s all slightly magical, in an altered states sort of way.

incorporeal states of mind or spirit, as well as hint at transcendence. The show was beautiful and eerie, dreamlike and occasionally chilling. There was a slightly morbid strain in the imagery on view, but it was tempered with stylistic wit in the work itself and the playfulness of the curation. Charles Addams might have brought an Edwardian folding chair to this one, the better to take it all in. David Hockney etched a simple rear view of the prince nudging his horse up to Rapunzel’s dangling locks. In Death the Strangler, Alfred Rethel engraved an image of a skeleton in a hooded monk’s habit pretending to play a fiddle with a pair of leg bones as people cowered around him. Max Klinger’s aquatint, Pursued Centaur, depicted three seemingly naked hunters chasing a centaur through long grass—right after the centaur has loosed an arrow backward into the leading horse’s neck. It shows you the moment when the hunters became the hunted. It’s all slightly magical, in an altered states sort of way.

But the revelation for me was a print from Picasso, the one of the blind Minotaur commonly considered the final image from The Vollard Suite—if you discount the concluding three portraits of Vollard required by the art dealer in his commission. I’d seen many prints from that suite before, but seeing it in person, for some reason, stopped me in my tracks. It was an entrancing exhibit, and this one print sent me briefly down a rabbit hole of study off and on during the past two months since my visit in January. Eventually, I’m going to post a long essay on The Vollard Suite—if I can sit still long enough to write it—because it has changed the way I think of Picasso and his career. I’m finding it hard to see anything else he did as equal to this suite of prints, especially if you consider Guernica the offspring of his years laboring on them.

The Vollard Suite is giving me a deeper respect for the sort of art—the kind of art that critics love because it can generate so much discussion—that doesn’t fit into my essentially modernist advocacy for visual art’s fundamental kinship with music, in the way it acts directly on the pysche, in contrast to language and narrative. Visual art and music are equipped to do something different from the meaning-making role of language, opening up an immediate sense of the world, but in a direct way that bypasses the intellect, and I consider this their most valuable role among all the arts. When this work gets tied to the notion of “meaning,” then visual art heads in a direction that usually seems less compelling to me. Yet the Vollard Suite is making me see the other side of this argument. It’s catnip for the thinking mind, but in such a way that it leads you toward the impenetrable paradox of Picasso’s own personal daemon. The Vollard Suite is a maze of implied, mysterious narrative, but it becomes, as Picasso is drawn toward greater and greater honestly about himself and his art, a work of tormented self-questioning and self-criticism. I’m not sure there’s anything else like it in his work, or in anyone else’s. It’s art that calls art itself into question. Out of this self-defeating struggle, one of the most worldly and pagan of 20th century artists created, in this image of the blind minotaur, a dead-end reverie of blind enchantment. It’s a depiction of himself as both baffled and instinctively creative with no way to see where he was going, yet obedient to the beauty that offered to lead him through his darkness. In a way, it’s an image of soon-to-be rejected grace. I think Picasso understood his own spiritual blindness. It’s his brief discovery of enchantment, as a consequence of his being honest about his inability to comprehend himself or his life, that takes him and the viewer by surprise. He had his secular equivalent to Beatrice in his teenage lover, Marie-Therese Walter, yet he parted ways with her. Yet while he created this print and its companions, she offered to light a path for him that he ultimately abandoned.

I was pleased and surprised when I got the notice that the Butler Institute of American Art wanted my painting of taffy for its Midyear exhibition, since other work had been rejected this year by our local museum and another regional gallery. After a decade of selling my work and showing it in juried exhibitions, it was still a game of percentages, entering these events. This year it might be only the two small museums that showed my work—Arnot and Butler—mostly because I haven’t had the time to finish enough work to enter other shows. Last year, I’d vowed not to enter anything larger than 24” in at least one dimension, and if possible enter nothing larger than that in any dimension. The difference in cost, and the amount of hassle that goes into the whole physical process of getting a painting to and from a show, is dramatic, when you exceed a certain size. But I had nothing else to enter, having submitted smaller paintings to other shows. So in the week I was home in Pittsford, I had to build a new crate, the largest yet, and figure out how to get it to Youngstown, Ohio and back.

I was pleased and surprised when I got the notice that the Butler Institute of American Art wanted my painting of taffy for its Midyear exhibition, since other work had been rejected this year by our local museum and another regional gallery. After a decade of selling my work and showing it in juried exhibitions, it was still a game of percentages, entering these events. This year it might be only the two small museums that showed my work—Arnot and Butler—mostly because I haven’t had the time to finish enough work to enter other shows. Last year, I’d vowed not to enter anything larger than 24” in at least one dimension, and if possible enter nothing larger than that in any dimension. The difference in cost, and the amount of hassle that goes into the whole physical process of getting a painting to and from a show, is dramatic, when you exceed a certain size. But I had nothing else to enter, having submitted smaller paintings to other shows. So in the week I was home in Pittsford, I had to build a new crate, the largest yet, and figure out how to get it to Youngstown, Ohio and back.

I get the same feeling looking at a close-up detail I shot a few months ago at

I get the same feeling looking at a close-up detail I shot a few months ago at

incorporeal states of mind or spirit, as well as hint at transcendence. The show was beautiful and eerie, dreamlike and occasionally chilling. There was a slightly morbid strain in the imagery on view, but it was tempered with stylistic wit in the work itself and the playfulness of the curation. Charles Addams might have brought an Edwardian folding chair to this one, the better to take it all in. David Hockney etched a simple rear view of the prince nudging his horse up to Rapunzel’s dangling locks. In

incorporeal states of mind or spirit, as well as hint at transcendence. The show was beautiful and eerie, dreamlike and occasionally chilling. There was a slightly morbid strain in the imagery on view, but it was tempered with stylistic wit in the work itself and the playfulness of the curation. Charles Addams might have brought an Edwardian folding chair to this one, the better to take it all in. David Hockney etched a simple rear view of the prince nudging his horse up to Rapunzel’s dangling locks. In