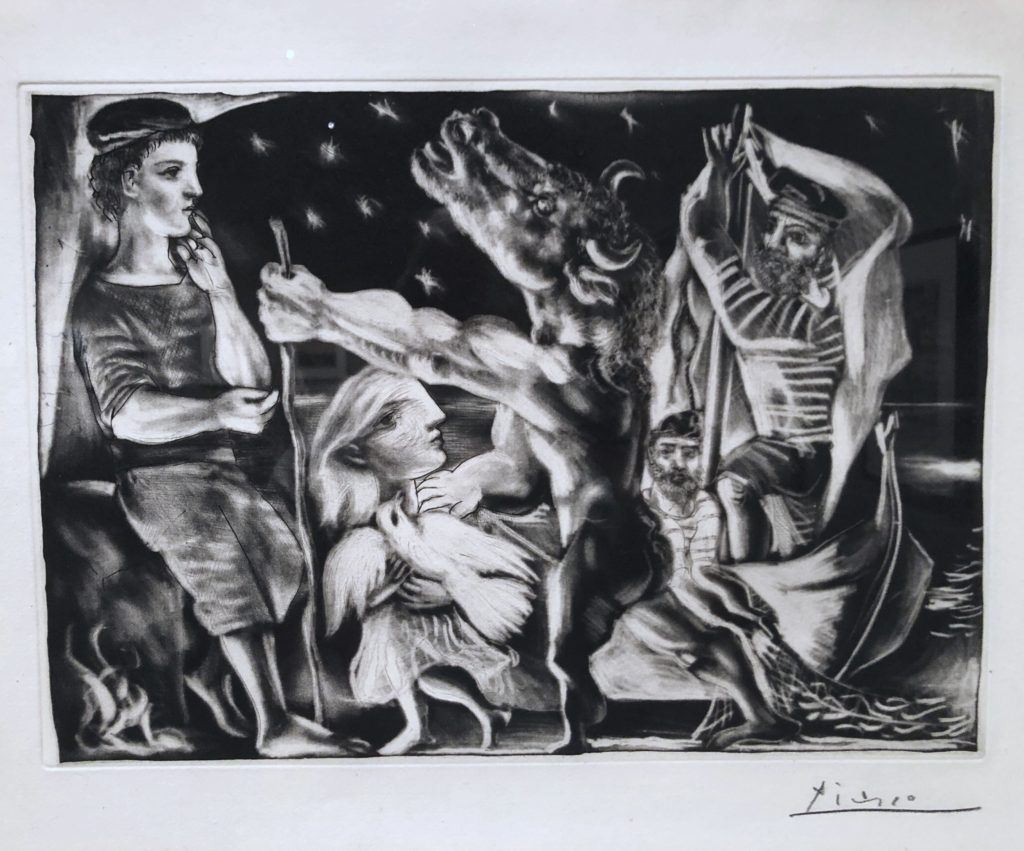

Picasso, the blind Minotaur

Pablo Picasso, Blind Minotaur Guided by a Girl at Night, burnished aquatint

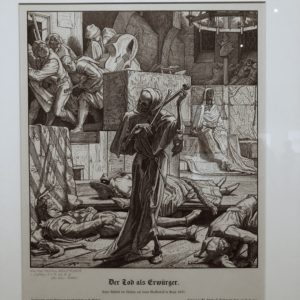

I’ve been surprised that the exhibit that has occupied my attention the most since my last visit to LACMA was Fantasies and Fairy Tales. It was a small, quirky collection of prints from around the year 1900. The aim of the exhibit was to show how, within this tight, curatorial window of qualifications (prints mostly within a narrow, fin-de-siecle range of dates), a selection of work could suggest  incorporeal states of mind or spirit, as well as hint at transcendence. The show was beautiful and eerie, dreamlike and occasionally chilling. There was a slightly morbid strain in the imagery on view, but it was tempered with stylistic wit in the work itself and the playfulness of the curation. Charles Addams might have brought an Edwardian folding chair to this one, the better to take it all in. David Hockney etched a simple rear view of the prince nudging his horse up to Rapunzel’s dangling locks. In Death the Strangler, Alfred Rethel engraved an image of a skeleton in a hooded monk’s habit pretending to play a fiddle with a pair of leg bones as people cowered around him. Max Klinger’s aquatint, Pursued Centaur, depicted three seemingly naked hunters chasing a centaur through long grass—right after the centaur has loosed an arrow backward into the leading horse’s neck. It shows you the moment when the hunters became the hunted. It’s all slightly magical, in an altered states sort of way.

incorporeal states of mind or spirit, as well as hint at transcendence. The show was beautiful and eerie, dreamlike and occasionally chilling. There was a slightly morbid strain in the imagery on view, but it was tempered with stylistic wit in the work itself and the playfulness of the curation. Charles Addams might have brought an Edwardian folding chair to this one, the better to take it all in. David Hockney etched a simple rear view of the prince nudging his horse up to Rapunzel’s dangling locks. In Death the Strangler, Alfred Rethel engraved an image of a skeleton in a hooded monk’s habit pretending to play a fiddle with a pair of leg bones as people cowered around him. Max Klinger’s aquatint, Pursued Centaur, depicted three seemingly naked hunters chasing a centaur through long grass—right after the centaur has loosed an arrow backward into the leading horse’s neck. It shows you the moment when the hunters became the hunted. It’s all slightly magical, in an altered states sort of way.

But the revelation for me was a print from Picasso, the one of the blind Minotaur commonly considered the final image from The Vollard Suite—if you discount the concluding three portraits of Vollard required by the art dealer in his commission. I’d seen many prints from that suite before, but seeing it in person, for some reason, stopped me in my tracks. It was an entrancing exhibit, and this one print sent me briefly down a rabbit hole of study off and on during the past two months since my visit in January. Eventually, I’m going to post a long essay on The Vollard Suite—if I can sit still long enough to write it—because it has changed the way I think of Picasso and his career. I’m finding it hard to see anything else he did as equal to this suite of prints, especially if you consider Guernica the offspring of his years laboring on them.

The Vollard Suite is giving me a deeper respect for the sort of art—the kind of art that critics love because it can generate so much discussion—that doesn’t fit into my essentially modernist advocacy for visual art’s fundamental kinship with music, in the way it acts directly on the pysche, in contrast to language and narrative. Visual art and music are equipped to do something different from the meaning-making role of language, opening up an immediate sense of the world, but in a direct way that bypasses the intellect, and I consider this their most valuable role among all the arts. When this work gets tied to the notion of “meaning,” then visual art heads in a direction that usually seems less compelling to me. Yet the Vollard Suite is making me see the other side of this argument. It’s catnip for the thinking mind, but in such a way that it leads you toward the impenetrable paradox of Picasso’s own personal daemon. The Vollard Suite is a maze of implied, mysterious narrative, but it becomes, as Picasso is drawn toward greater and greater honestly about himself and his art, a work of tormented self-questioning and self-criticism. I’m not sure there’s anything else like it in his work, or in anyone else’s. It’s art that calls art itself into question. Out of this self-defeating struggle, one of the most worldly and pagan of 20th century artists created, in this image of the blind minotaur, a dead-end reverie of blind enchantment. It’s a depiction of himself as both baffled and instinctively creative with no way to see where he was going, yet obedient to the beauty that offered to lead him through his darkness. In a way, it’s an image of soon-to-be rejected grace. I think Picasso understood his own spiritual blindness. It’s his brief discovery of enchantment, as a consequence of his being honest about his inability to comprehend himself or his life, that takes him and the viewer by surprise. He had his secular equivalent to Beatrice in his teenage lover, Marie-Therese Walter, yet he parted ways with her. Yet while he created this print and its companions, she offered to light a path for him that he ultimately abandoned.

Comments are currently closed.