The magic of the everyday, domestic, and mundane

Tangible Things, invitational group show at Main Street Arts, Clifton Springs

Main Street Arts invited me to show some of my taffy paintings in its current exhibit, Tangible Objects, along with the work of six other artists who are experimenting with form and materials, and whose work in many cases evokes commonplace, overlooked objects. In other words, Bradley and Sarah Butler recognized that someone who tries to bring forth the sense of a world in a couple pieces of salt-water taffy would be right at home with these others: all of us are exploring the formal opportunities afforded by the most humble, vulnerable objects most would consider insignificant. In other words, the spirit of still life painting hovers throughout the show: the beauty and resonance of the everyday, domestic, and mundane. I was also delighted to see my sense of being haunted by color field painting (in my candy paintings) is echoed a bit in the work of one of the other artists, Myung Urso, whose materials are fabric and paper. It’s a great show, and the work is original, surprising and often quietly poetic and stirring.

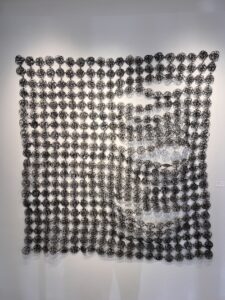

Becca Barolli, weaves stiff, annealed steel wire into shapes that suggest fabric—an old, falling-apart afghan, a long muffler—bending the wire and braiding it into these nearly immovable effigies of something far more warm and cuddly. She works long hours, rubbing CBD oil into her fingers at the end of a work day, trying to weave with steel—it’s almost a vocation the Greeks would have imagined as karmic justice for some offense against tunics. The objects suggest petrified remains of what once nurtured  comfort and life, but they aren’t morbid, nor depressing. Instead, the immense, repetitive effort, the meditative devotion required to transform the body of supple, humble things into art gives them a mysterious totemic after-life. The contrast between the delicate, original object, and the work based on it, impervious as chain mail, accentuates the gap between the medium and what it represents as well as the delight triggered by that gap in all representational art, fusing both sameness and difference into one perception. Barolli is a recent MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and has had a residency at Mass MoCA and has shown at galleries in L.A., New York City and San Francisco. Her practice favorably brings to mind Susie MacMurray’s, and it would be interesting to see them paired in a show some day.

comfort and life, but they aren’t morbid, nor depressing. Instead, the immense, repetitive effort, the meditative devotion required to transform the body of supple, humble things into art gives them a mysterious totemic after-life. The contrast between the delicate, original object, and the work based on it, impervious as chain mail, accentuates the gap between the medium and what it represents as well as the delight triggered by that gap in all representational art, fusing both sameness and difference into one perception. Barolli is a recent MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and has had a residency at Mass MoCA and has shown at galleries in L.A., New York City and San Francisco. Her practice favorably brings to mind Susie MacMurray’s, and it would be interesting to see them paired in a show some day.

At first, Sue Blumendale’s dresses look as if they could be worn to a party, but they’re made of archival copy paper that serves as a support for digital images of people from her ancestry: mother, father, aunts and a grandmother she never met. The dress becomes a sort of sculpted image of an absent human form, missing from inside the dress but commemorated with two dimensional images printed on the paper. The pictures of her family come from a family album. It’s intensely personal and felt, and the humble quality of the dresses has an almost Japanese quality of self-effacement, the everyday object surviving, transcending its wearer, coming into its own, and likewise, the artist herself withdrawing to let the dress shine, just as the subject, the missing person is absent inside the dress but present in the memorial pattern. It’s the transformation at the basis of all art: the individual human being sublimated into the creation. These are wonderfully realized three-dimensional images, where stylistic choices come together perfectly in a unique way. It’s lovely, intensely personal work. One wonders if someone could make a living doing cloth versions of these dresses to be worn, on commission, for people who wanted to clothe themselves with a memory. A new form of portraiture and a new line of clothing that exhibits the work anywhere, at any time.