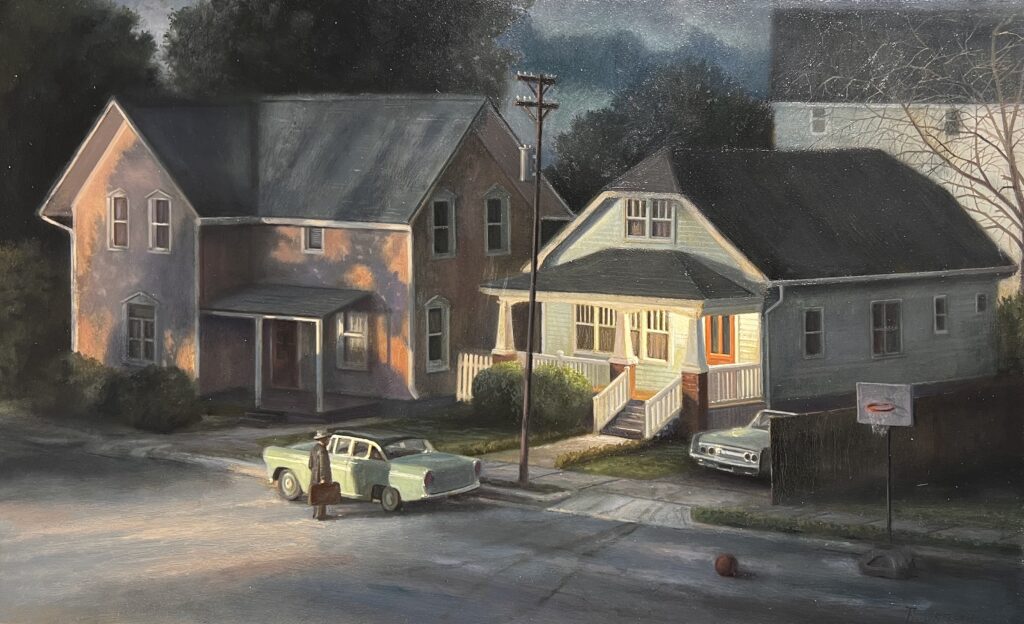

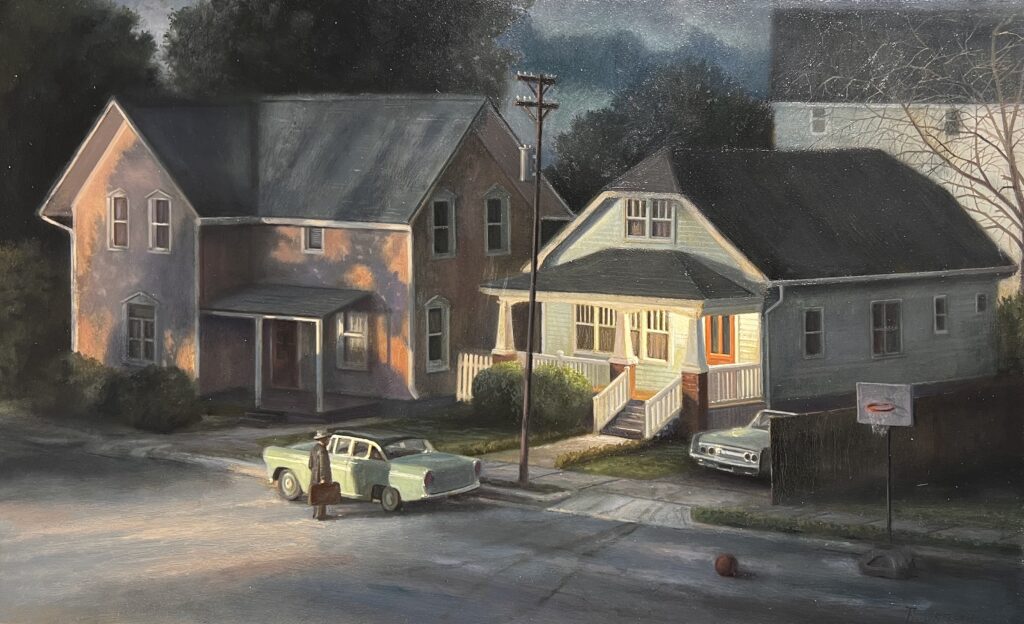

September 14th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Landlord, oil on panel, 16″ x 26″

It’s hard to believe it’s been more than a decade since James Casebere’s photography was included in the Whitney Bienniel. I remember, back in 2010, being wowed by his reproductions of the suburban dioramas he painstakingly constructed and then lit and shot. His work seems to have gotten more austere and cerebral and political since then, but his landscapes of newly-built suburban dream homes still convey the ambivalent beauty of an increasingly unaffordable American Dream. Casebere centered the simplicity of his scenes at the median point between verisimilitude and minimalist geometry of newly constructed McMansions. His houses stand on an otherwise almost naked slope with newly-planted saplings a quarter century away from offering privacy and shade. Anyone who has lived in a new suburban tract knows the mix of feelings: the exhilaration of moving in, the weird sense of emptiness and exposure in a place without foliage, the smell of new construction and the sounds of new doors clicking into place, as well as the paradoxical solitude of tract housing jammed side by side into narrow lots. Casabere’s dioramas were about American life, as it is experienced by those lucky enough to buy a home—how much more poignant now in the current real estate market these scenes must be for young people hoping to put down roots. Yet his houses jutted up in various colors, evoking geometric abstraction, like the structures in an Icelandic landscape by Louisa Mattiasdottir. It was stunning work and it stirred many conflicted feelings—yearning, hope, and the inevitable disappointments of routine.

He was one of those art stars of the moment, using dioramas to make two-dimensional images, like Gregory Crewdson, on an even larger scale, whose constructed scenes—far more realistic and detailed—have a cinematic power and a darker, but even more alluring mood. Crewdson lives on the edge of popular culture. There’s a sense of epic effort in his illusions that seem imbued with an invisible presence. Built by hand and then captured with photographs, his work would be familiar to anyone who listens to Yo La Tengo (where I discovered it on one of their album covers) or watched Six Feet Under. His art was mentioned on the show, and he was recruited to do a promotional campaign for it.

It’s been years since I’ve looked into diorama art, so it took me a while to even come up with Casebere’s name, MORE

September 12th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Le bapteme, Marc Padeu, 78″ x 110″

On Saturday, I wandered lonely like a cloud through The Armory Show, at the edge of Hudson Yards. That domineering real estate venture is the child of our precarious finance-driven economy. It’s a forbidding, crystalline, Antarctic Fortress of Solitude rising up along the river, with Dubai-like heights so reflective its towers almost disappear against the sky. Across the street, a honeycomb of gallery booths spread out in uniform ranks inside the equally glassy, tourmaline facets of the Javits Center. (By contrast with the glass towers, the Center looks more like an enormous multi-story greenhouse.) Inside, at this annual pop-up art mall, rows of booths gave birth to another seemingly endless grid of tight little alcoves as I slowly made my way through the maze, swiveling my head in all directions, trying not to miss anything, as if riding through Pirates of the Caribbean.

The beautiful people were there in abundance, trying to look as chill as the champagne in ice buckets beside their plush chairs. So much money, but how much of it was being spent? I don’t know the break-even point for a gallery—how much needed to be sold to make a profit after the fee for a booth—but few of the people staffing these booths looked light-hearted. Most had a selection of work from their roster, while quite a few staked their investment on a solo show of only one artist. The solo shows were invariably the most interesting.

The free market is a necessarily brutal place, even at this lofty level. A corner bodega probably has an easier time turning a profit than many of the souls who must spend months preparing to ship this costly work overseas and put it up for sale at a fair. Represented were 250 galleries from around the world, but after an hour of walking, it felt like far more. It was often depressing, so much of it a cavalcade of disposable and over-hyped art. But that isn’t far from the experience of walking through Chelsea and ducking into one gallery after another. New York City is changing and has been for many years now. I miss being able to wander into Danese-Corey and never being disappointed. I miss OK Harris downtown. I also miss the Half King. And Hi Fi in the East Village. And the lines outside the Upright Citizens Brigade on 26th. All gone. Fine, so one is a restaurant, and another is a little bar/music studio, and another a school of improv, but they are similar disappearances of the past decade and were small bastions of quality or history or what will probably be considered Old New York in only a few years. Manhatttan needs another Maeve Brennan or Joseph Mitchell to document this metamorphosis, this infiltration. You feel as if you’re watching from the shore as art rides the froth of a giant wave of international money sweeping aside graceful little figures who managed to stay vertical on economic swells of smaller, more human dimensions. (There are notable survivors, like Arcadia Contemporary, whose scale is in all things extremely human. It didn’t need a booth at this show, because it is killing at its SoHo location, having sold out its entire new show at the opening on Thursday.) So it can still be done, old school, if the goal is to make enduring art rather than spectacular profits.

MORE