Archive for November, 2022

November 30th, 2022 by dave dorsey

A painter’s impossible challenge, as well as the essence of painting, from The Little Prince.

And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: it is only with the heart that one can see rightly, what is essential is invisible to the eye.

–Antoine de Saint-Exupery

“The narrator becomes an aircraft pilot, and one day, his plane crashes in the Sahara desert, far from civilization. The narrator has an eight-day supply of water and must fix his aeroplane. Here, he is greeted unexpectedly by a young boy nicknamed “the little prince.” The prince has golden hair, a loveable laugh, and will repeat questions until they are answered.

The prince asks the narrator to draw a sheep. The narrator first shows him the picture of the elephant inside the snake, which, to the narrator’s surprise, the prince interprets correctly. After three failed attempts at drawing a sheep, the frustrated narrator draws a simple crate, claiming the sheep is inside. The prince exclaims that this was exactly the drawing he wanted.”

November 27th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Phyllis Bryce Ely, Seneca Lake, Looking South, oil on linen, 12 x 16, 2019.

Phyllis Bryce Ely has been doing en plein air paintings of the nearby Finger Lakes, one of which is on view in Spellbound: The Art of Mystery at Oxford Gallery. I keep coming back to this image she sent me, at my request, a while ago. It’s less abstracted than much of her work, and more reliant on the shape of the brush and the flow of the paint for the cool tension between the accuracy of the paint and what I’m seeing through it. What I love is how loose and yet carefully precise it is. This isn’t really bravura brushwork, it’s more personal than that: it has her touch, the ghostly, translucent gradations between tones. Much of what Ely does is less like what one would actually see standing at a scenic pull-off, more like the Group of Seven or at least Lauren Harris, but Ely’s work is even more about the paint. This one creates a very real and precise sense of a three-dimensional view and yet looks utterly free and spontaneous in the way she applies the paint.

November 24th, 2022 by dave dorsey

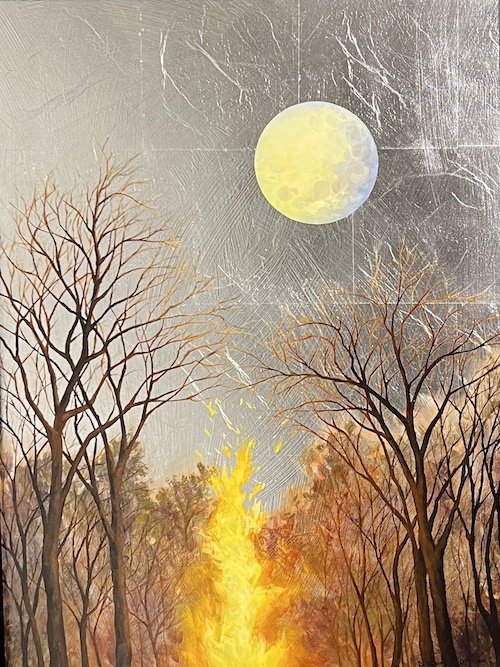

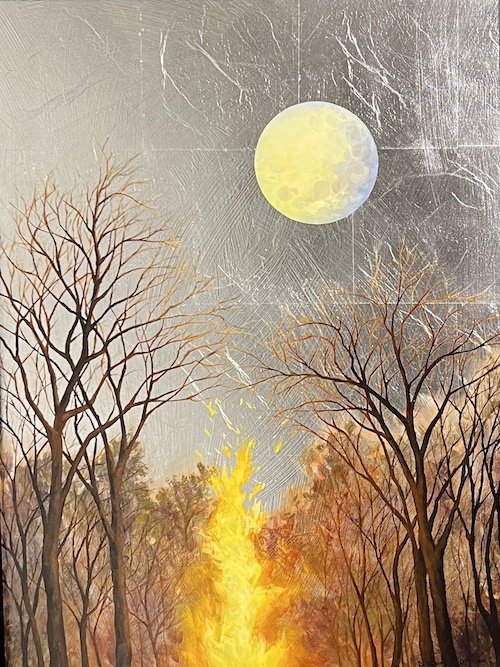

Bonfire Moon, Bridget Bossart van Otterloo, oil and silver leaf on board.

At Oxford Gallery many of the participating artists responded to the theme of the new group show—Spellbound, the Art of Mystery—with compelling work.

When I first walked through the gallery, I passed a welded steel raven from Wayne Williams with a cursory glance at the bird, but then on a second tour of the show, I paused and looked at it from various sides and began to absorb the dignity of the crusty, ruffled creature. It began to remind me just a bit of Donatello’s Lo Zuccone, a prophetic  interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible.

interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible.

Anthony Dungan’s large abstract acrylic on canvas, Saucerful of Secrets, almost side-by side with the raven, represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.

represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.

At first glance, William Keyser’s Inexplicable Lacuna appears to be a joyous pastel homage to a Matissse cut-out or one of Milton Avery’s women assembled with flat, simplified color. Yet it has a mysterious dark black line stamped MORE

November 21st, 2022 by dave dorsey

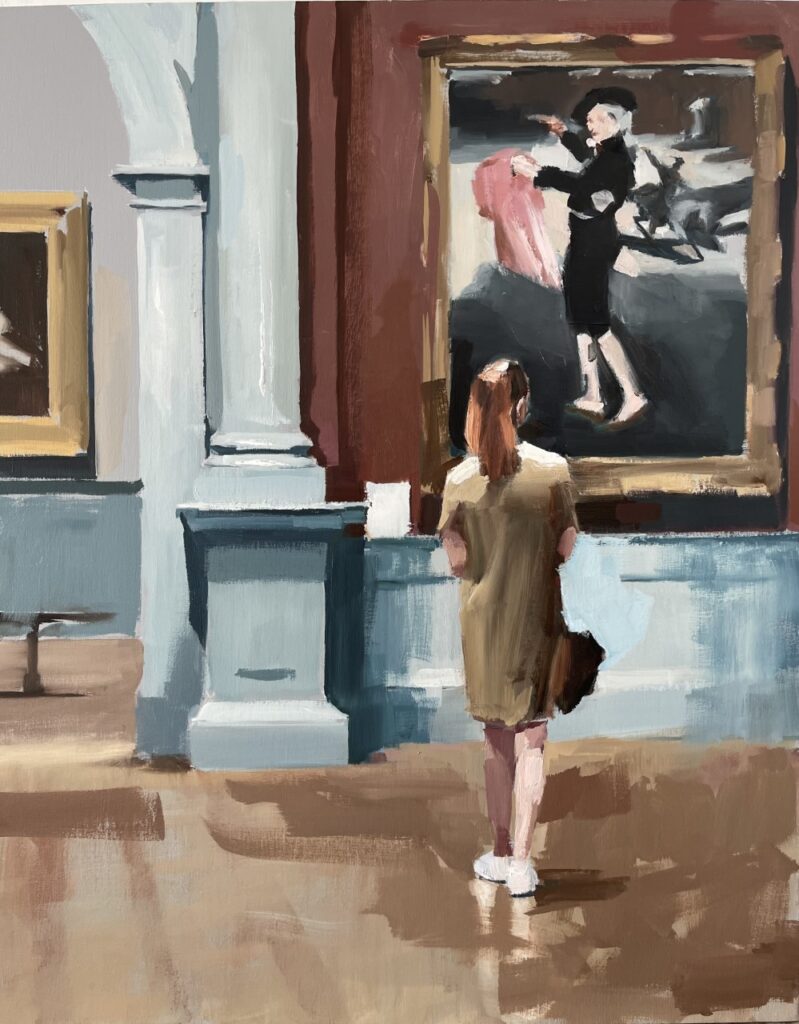

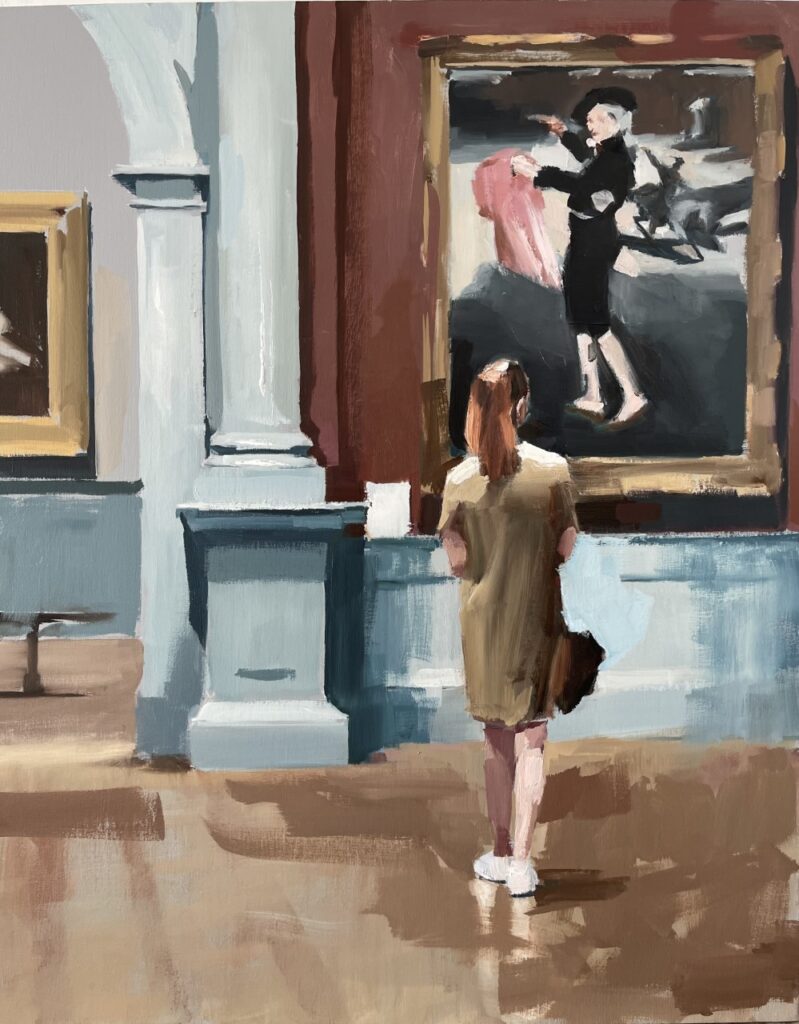

Mark Tennant

It’s a lovely candid moment, a young woman pausing to study a Manet at the Metropolitan. It’s one among a series of paintings Mark Tennant has done from what could be a field trip of female students milling through the museum. It seems to eschew his typically prurient or declasse subjects, a departure for Tennant whose metier is mostly a dour and slightly Calvinist glare that exposes the seamier precincts of human desire and behavior in depressingly raw terms. His subjects range from streetwalkers, cocktail parties that look like clueless celebrations in the eye of the social hurricane in the 1960s (or in Portland and Seattle, circa 2020), Zsa Zsa Gabor’s driver’s license pic, moments of drunkenness, public making out, many many exposed teenage legs going up and down stairs or posing in a variety of places that make them seem Spring Breakishly available for mischief, and a killer under arrest viewed in Gerhard Richter black-and-white. Most of these are photographically sourced from flash-lit freeze frames, offering him black outlines that push his figures forward. Much of it seems a dark celebration of the despised male gaze skulking at the edge of legality. What a relief to see a well-behaved girl tamed by the greatest of the Impressionists. But wait. Even here, if you try enough search engine queries, it turns out the Manet has a little transgender touch that pulls the knowledgeable viewer out of the comfort zone and into the present: Mademoiselle V in the Costume of an Espada. A young woman as matador, drag king in mid-19th century Paris. In his sly au courant way Tennant has stuck to his program: the notion of normality is a relic. It was on the wane already back then at the birth of modernity, when Manet’s nude enjoyed lunch on the grass with a couple fully dressed men. By contrast, the subject matter is what’s least interesting with Tennant, but it appears to bring him a huge following, a Pamplona stampede of fans if you check his Instagram. I suspect the seedier side of his imaginative home is a decoy. Like that pink cape, it draws you close enough for his brushwork to slay you. Those killer marks recommend him to anyone who paints.

November 18th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Drea Cofield, Mantis, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches, 2021

Drea Cofield’s more recent work has an idiosyncratic way of engaging visually with the natural world that brings to mind Burchfield and

Nick Blosser, though her work seems closer to the spirit of animation. Burchfield is one of the few non-Asian painters who have depicted cicadas, and not just the legs, wings, and thoraxes, but also their rattlesnake, high-frequency whine. Cofield does insects in an equally interesting way. There’s a charmingly Disneyesque but disquieting air to her praying mantises. Some of her natural scenes are simplified but exacting in the way they capture the light on the deformities of old trees in a drab unpicturesque acre of woods most painters wouldn’t give a second look. All of her current work departs dramatically from her earlier Day Glo caricatures of naked figures cavorting in strange ways in erotic fever dreams. In the image above, the vestigial naked figure is submerged, shimmering under sunlight filtered through the water’s rippled surface. You hardly realize you’re being mooned. Mostly, the new work looks outward at nature, from within the house of her style, to produce carefully observed images of what’s there in the world, not just in her mind, though her vision is a strong and simplifying filter. I’m sorry I missed her work in my visit to The Armory Show. Here’s her bio from Exeter Gallery, a Matt Klos joint in Baltimore celebrating its fifth year of operation (congratulations Matt) exhibiting mostly perceptual painters:

Drea Cofield has created a sensuous and saturated world in her new series of paintings for Soft Limbs. The series depicts the cycle of a day: sunrise, sunset, and night illuminated by cool lavender light. The show is on from Nov. 14th-December 31st. Come celebrate with the artist at a reception on Friday, November 18th from 5-7pm.

Drea Cofield is an artist currently working between Indianapolis, IN and Brooklyn, NY. In 2013, she received her M.F.A from Yale School of Art (New Haven, CT), and in 2008, her B.A from DePauw University (Greencastle, IN). She has exhibited in the U.S. and internationally including New York, Los Angeles, and Perugia, Italy. Most recently she exhibited in the Armory Show with 1969 Gallery in New York; solo exhibitions at the Tube Artspace in Indianapolis and DePauw University. Upcoming exhibitions include a solo exhibition at Exeter Gallery in Baltimore, MD. Her work has been featured in the Brooklyn Rail, Artnet News, Juxtapoz, Blouin Art Info, and in Suzanne Hudson’s latest issue of Contemporary Painting (World of Art). She is the recipient of an Elizabeth Greenshields Grant and the Yale University Gloucester Painting Prize. Residencies include the Guild of Adventure Painters SWAB Mobile Residency in 2019. She is the Founder and Director of Bomb Pop-Up, a pop-up Art & Music initiative that focuses on providing visibility in exciting contexts to emerging and established artists and musicians, working with over 200 artists from all over the world and collaborating with institutions such as the National Academy of Design. Cofield has been a visiting artist at Cooper Union, Pratt Institute, and a returning critic at the School of Visual Arts. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Art at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana.

November 15th, 2022 by dave dorsey

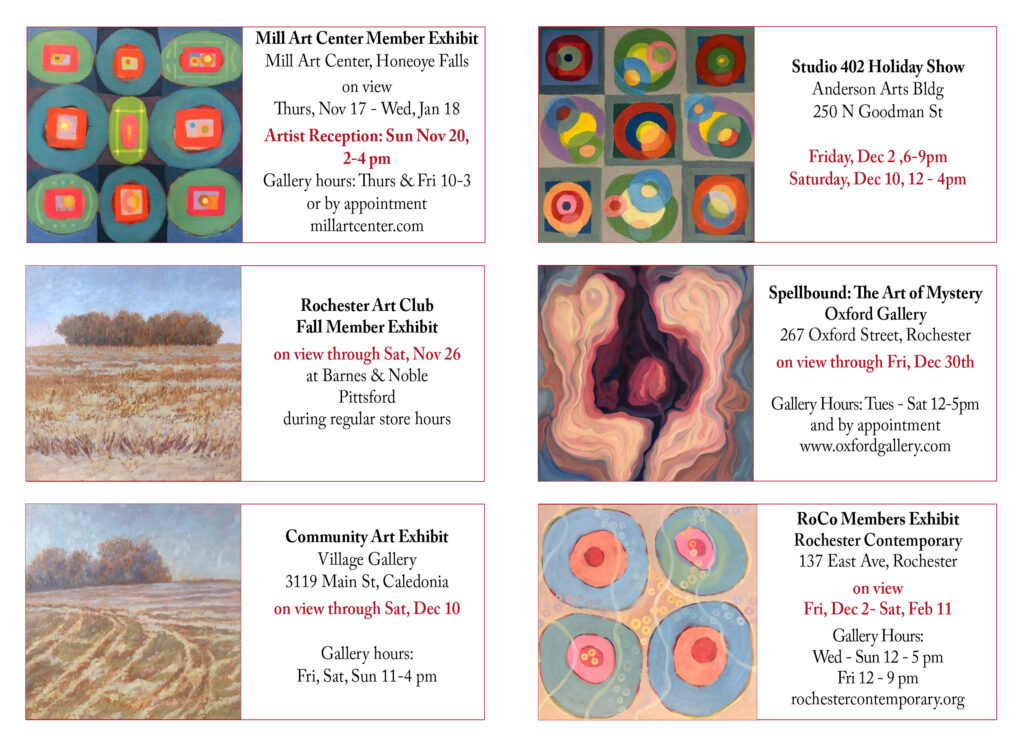

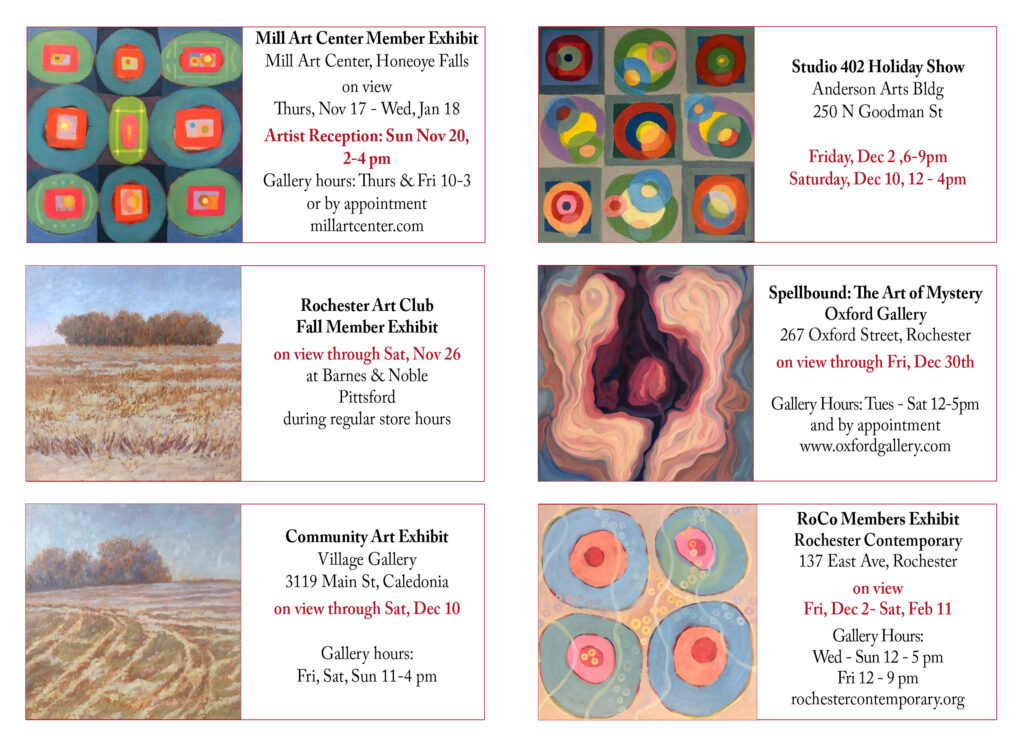

Above are multiple opportunities to see new work from Jean Stephens, including the current excellent group show at Oxford, Spellbound: The Art of Mystery. It’s well worth the effort to take a look.

November 13th, 2022 by dave dorsey

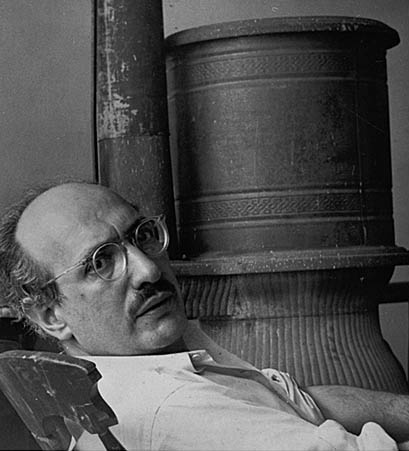

Here’s a pretty well-known quote in context. A part of the context is that it is from Selden Rodman’s book. The telling of it printed here is the most accurate that we’ve got, and perhaps this is relevant as I’m seeing it condensed or misquoted in memes often.

“You might as well get one thing straight,” he said, relaxing, “I’m not an abstractionist.”

“You’re an abstractionist to me,” I said. “You’re a master of color harmonies and relationships on a monumental scale. Do you deny that?”

“I do. I’m not interested in relationships of color or form or anything else. I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on — and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate those basic human emotions… The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point!” – Selden Rodman, Conversations with Artists.

November 8th, 2022 by dave dorsey

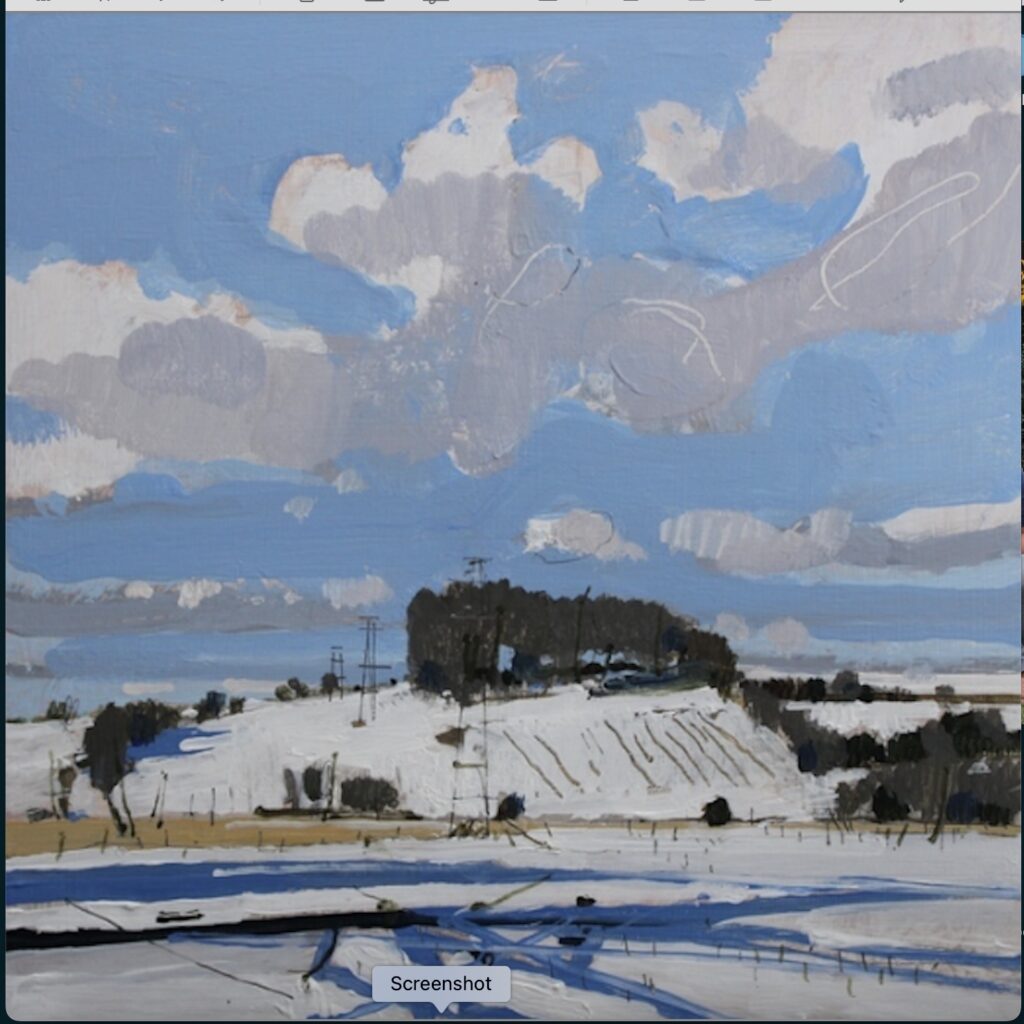

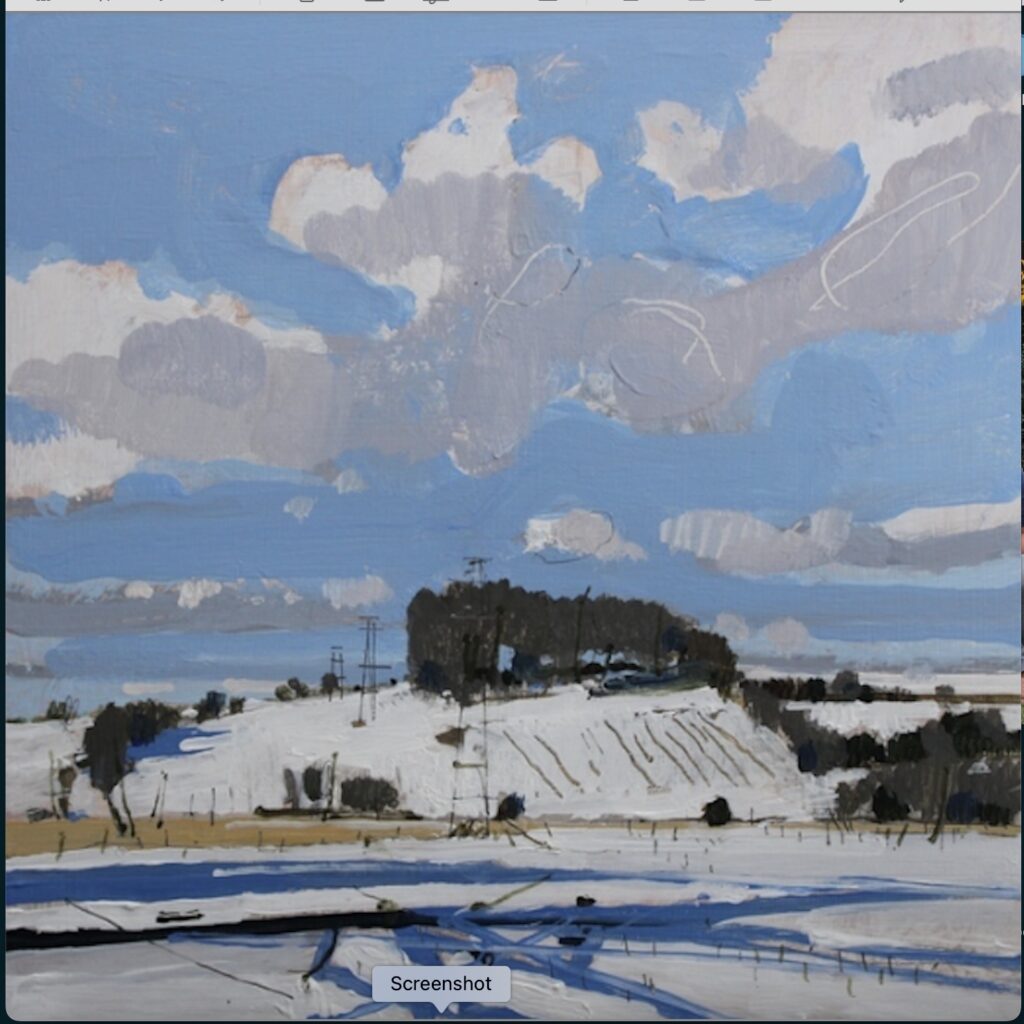

Harry Stooshinoff, 10 Saved Acres, February 20, Acrylic on birch panel

I hope Harry doesn’t mind if I repost most of his latest newsletter. Note his use of the word rubbish. So much of good art depends on chucking that particular quality out, especially prohibitions based on consideration of anything that diminishes the intensity of energy one applies to a painting. His letter is so full of wisdom and expresses so well what it’s like to try and maintain this creative energy in painting. My mom died in April and I’ve spent the past six months, in which I’ve had to pull away from painting quite a bit, thinking about what I want to do as a painter from here on, and I’ve been drawn toward several different paths, without actually getting back to daily work yet. Soon. But I’ve been wanting to work in several modes concurrently and this newsletter offers a lot of encouragement.

Harry talks about this kind of juncture directly. He advises that you do what energizes you, what you most want to see when you are done, not what you think you should be doing based on any other consideration–market, past work, reputation, what other people think, “branding”, whatever. What I admire in Stooshinoff’s painting is how it reflects two kinds of work I’ve deeply loved in the past: Asian art, especially Japanese sumiye painting and Fairfield Porter’s paintings in the 50s and 60s. I’m not sure he considers either of these major influences for his work, but it’s what I recognize through his work. In the background lurks Matisse of course, casting his enormous light-filled shadow, but you don’t get to him from Stooshinoff’s work except through Porter. Mitchell Johnson is another artist doing something very connected to this kind of painting, with Porter and Matisse as a backstory, but without the Asian element for me.

Harry works quickly, very quickly, premier coup, as Dickinson expressed it, and yet his use of value and color convey how light and form in landscape actually looks. That’s the marvel. He’s a loose painter, and you can often see pretty clearly how he makes his marks. There’s no attempt to refine the evidence of his hand. The application of acrylic flows off his brush in what appear to be spontaneous gestures, but if you drill down into the details you see some very straight lines, hatch marks almost as regular as Durer’s, and exacting precision everywhere, even if some of his hills are stylized, more like karst mounds in China. I don’t think you see this terrain in Canada, but maybe the humpy kames and eskers we have down here south of Lake Ontario are common directly to the north of us on the other side of the lake. That paradox, the marriage of generalized forms and gestural marks with visual exactitude where one area of value ends and another begins reminds me of the paintings Fairfield Porter did when he was clearly using photographs as sources. Stooshinoff works from sketches done immediately in response to a scene that strikes him as arresting. His work looks abstracted from the actual vision of a landscape, but it’s more a kind of involuntary shorthand without any pretensions: just a man working under the pressure of his passion to convey what he sees, with an urgency to move on to the next moment of looking. It isn’t some sort of transformation of what’s seen into something more interesting or valuable than an original glimpse of an actual hill with a clouded sky overhead. He just wants to be a conduit of what’s already out there, in his own quiet, quick way. Here’s his newsletter:

There really are 1000s of ways to make paintings. And I’m not just talking about the history of art and other people. There are 1000s of ways for YOU and ME to make paintings. Perhaps we think we paint the way we do because we evolved naturally onto this path, this style, and so this is our signature ‘style’ that is somehow essential to our artistic quality and integrity. That may or may not be true, and mostly I think it’s untrue. Artists have been fed lots of rubbish through the decades that, for the most part, they have internalized. Whatever artistic path we stay on is a choice, and it’s a choice we make every day. You can wake up tomorrow and make a different kind of picture. Keep in mind that for years artists feared that their dealers might say something to this effect, “….you look like you’re all over the place and jumping around too much…keep within this style that you’ve made popular and that you’re now known for”. Hmmm…branding, and all that. Again, there is some good sense in this sentiment. Sometimes it’s obvious when an artist is not committed enough and is simply flailing in multiple directions. But, the inverse is so evident as well. Artists should not harness themselves in too tightly, for market reasons, or any other reasons.….if the need is felt, there is always room to explore more, in style, method, direction, or subject.

MORE

November 1st, 2022 by dave dorsey

Reverie #5, Bill Santelli, arcylic on paper.

One of Bill Santelli’s recent pieces on paper: he’s doing what I’ve been hoping for years he would do, building a composition without his typical geometric partitioning. Small work, on paper no less, but it offers the sense of a cosmic view, though it also gives me the impression of looking skyward at night or gazing up through water toward the surface in a colorful reef. And, on top of that, the image seems to map inner states in a 60s way. Marvelous.

interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible.

interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible. represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.

represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.