My slow path to painting

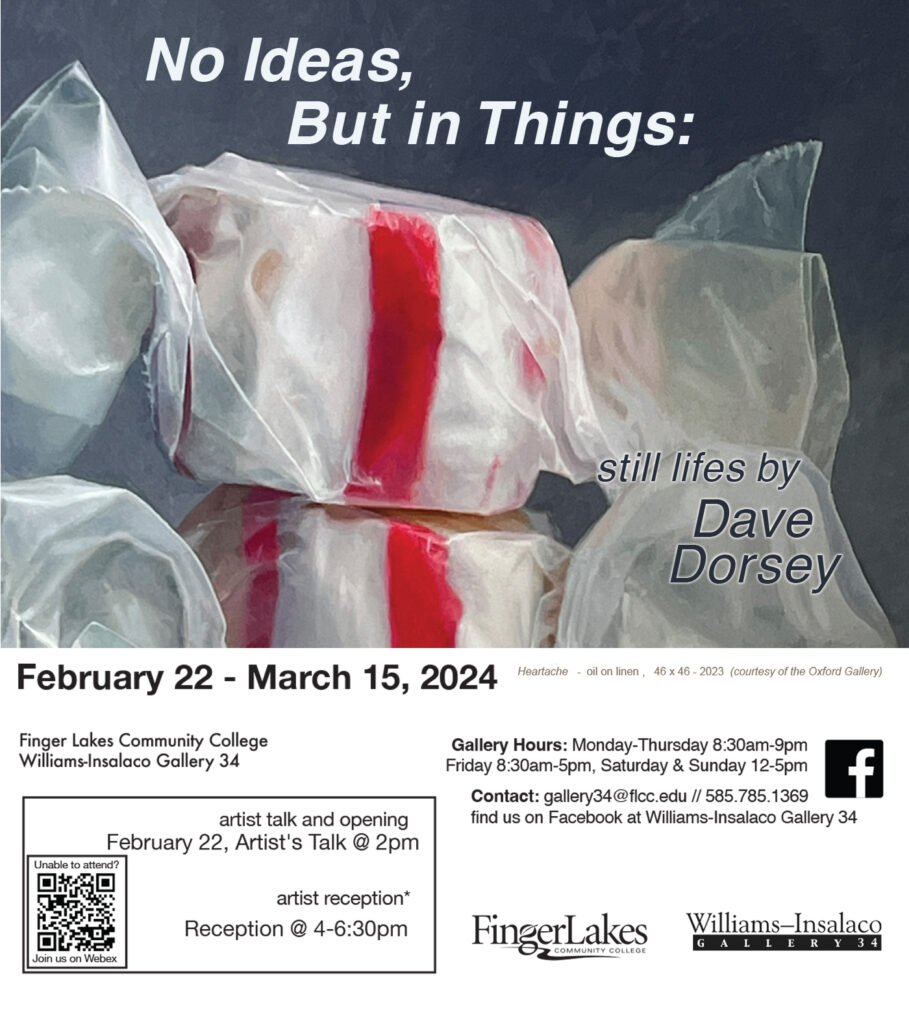

I’m going to deliver about eighteen paintings to the Williams-Insalaco Gallery today for a solo show opening next week: No Ideas But In Things. It’s the motto coined by William Carlos Williams for the Imagist poets a century ago. The exhibition is a survey of work I’ve done over the past decade. I’m giving a talk mostly for the art students at FLCC, describing my slow progress to where I am now as a painter. I’m going to open with my wisdom about being a painter, reduced down to five words: Don’t quit your day job. This was a crucial choice for me, to make money in other ways and make paintings in the time that remained. (I still have the vestige of a non-art day job, though I work full days as a painter.) This choice delayed my ability to become a professional artist, but also gave me the freedom to experiment and simply learn to absorb what I loved in the work of others and learn from it at my own pace. I think highly ambitious artists who are determined to go to Yale or Pratt and then start exhibiting in New York City and selling for high prices within a few years of having gotten an MFA are at risk of losing touch with what drives them to be an artist. Anyone who succeeds commercially in short order will, of necessity, be under pressure to adapt to the demands of collectors and critics. A painter can easily lose touch with what prompted him or her to make art in the first place.

I didn’t go to art school for a couple reasons. One, I didn’t feel at home with much of what was going on in the art world in the 1960s when I was in my teens and in love with the work of the early modernists: Van Gogh, Gauguin, Chagall, Braque, Klee, Matisse, Burchfield, and others. As art progressed into the mid-20th century it became less and less appealing to me. I felt like a late-comer. I thought that I had to somehow fit into my historical moment, so effectively this opportunity had come and gone before I was born. But I also began to wonder how the practice of painting could progress at all beyond the work of the abstract expressionists and color field painters. It seemed as if painting had run its course. A cluster of other, weirder ways of being an artist had sprung up in a desperate attempt to keep the idea of the avant garde alive. Performance art, happenings, minimalism, conceptual art, installations and so on. Everyone was struggling to do something new when the idea of newness had exhausted itself. It all seemed contrived and arbitrary. It seemed painting had nowhere else to go. This didn’t keep me from painting. But I assumed I would need to do it simply because I enjoyed it without any hope of finding a way of belonging to an art scene that had moved beyond me. So I kept painting without attempting to make a living from it. I avoided a degree in art, even though in my thirties I studied at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute and the Memorial Art Gallery.

I got a master’s degree in English, became a reporter, got jobs in newspapers and then with MORE

My work will be shown by Arcadia Contemporary at the 29th edition of The West Coast’s largest, international art fair,

My work will be shown by Arcadia Contemporary at the 29th edition of The West Coast’s largest, international art fair,