A half-century continuum

Jean and Bill Stephens, courtesy RIT

There are a few days left to see Continuum, the current exhibit of new work by Bill and Jean Stephens. They are both long-time art educators who met and fell in love at Rochester Institute of Technology fifty years ago in the printmaking studio on a floor above the one where their work now hangs.

The work is arranged almost symmetrically, in an alcove open to the main exhibition space filled with politically motivated fiber art. (Some of the adjacent fiber work is quite good, extremely well crafted and almost childishly subversive given the soft, amiable quality of the medium.) It’s an apt curation, each exhibition contributing to the spirit of the other. Jean’s subtle and spiritually suggestive collages alternate on the walls with Bill’s abstract paintings in acrylic ink and gel pen. Husband and wife, this creative team has been improvising new work for decades, responding to first marks and finding a way forward toward a sense of completion in whatever medium they choose. In his dark paintings, the imagery comes forward from a black ground of permanent ink he lays down over the entire support. He removes the ink with an alcohol solution and then makes marks with fine-point white gel pens. Bill’s soul resides in the drawing, the almost microscopic-looking marks—thousands of them—that move in waves across the surface of each painting. In others he erodes the blackness into egg-shaped modules, like jostling cells, that form designs he doesn’t anticipate but discovers as he works.

Jean creates gelli prints building new textures of color with a brayer, and then she assembles portions these prints as a collage, along with found objects such as postage stamps or newsprint or columns of text or shreds of maps. In many of the pieces on view, she improvises her own imagined ancient script, which looks Middle Eastern. It’s quite persuasive, and on these faux Arabian lines she creates a sense of flow and assurance, like a master calligrapher’s brushwork. Jean told me she isn’t saying anything in particular in this automatic writing, simply channeling script in a tongue not yet defined. The work is playful and associative and brightly affirmative, dreamlike—the words sweet and spot serve as bookends for one images. It’s all essentially as improvised as her husband’s paintings. Her collages often look like disassembled and rearranged modernist mandalas, with north south east and west wings.

As a whole the entire show is introverted—in the sense, say, that Paul Klee’s paintings were introverted—and very understated. It’s quiet the way someone who would like to be heard speaks so softly you pay closer attention.

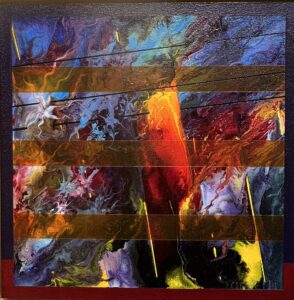

Flash Instant, acrylic Bill Santelli

I gathered with some other artist friends to talk about the show and our life as artists: Bill Stephens, Bill Santelli, Barron Naegel, and William Keyser. Stephens talked about how he works, but his process is instinctive and meditative; he doesn’t indulge in the kind of art-statement doubletalk that so many artists use to inject a bit of fuel into a career. We sat in a circle at one of the tables in the School of Art and Design in Booth Hall.

Stephens: I work with permanent acrylic ink, Caran D’ache crayon and white gel pen. I put down the black background and then remove it with alcohol wipes.The whole painting is done in black acrylic ink and I go in with 70 percent alcohol wipes and remove the ink to create shapes. The ovals are made using my finger. I pick up the texture of the canvas underneath. Then go back in with a fine point pen. White marker on top of the black. I had a young woman recently ask me, Mr. Stephens, when do you know when a painting is done? When I die, I’ll let you know that it’s done.

Santelli: How do you feel about where you are in your work?

Stephens: Good. I’m always experimenting. That’s all I’ve ever done. It’s coming together.

He keeps laughing after he says this, suggesting that his work MORE