A half-century continuum

Jean and Bill Stephens, courtesy RIT

There are a few days left to see Continuum, the current exhibit of new work by Bill and Jean Stephens. They are both long-time art educators who met and fell in love at Rochester Institute of Technology fifty years ago in the printmaking studio on a floor above the one where their work now hangs.

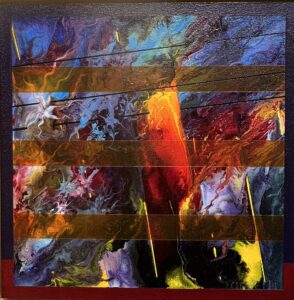

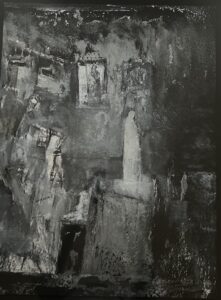

The work is arranged almost symmetrically, in an alcove open to the main exhibition space filled with politically motivated fiber art. (Some of the adjacent fiber work is quite good, extremely well crafted and almost childishly subversive given the soft, amiable quality of the medium.) It’s an apt curation, each exhibition contributing to the spirit of the other. Jean’s subtle and spiritually suggestive collages alternate on the walls with Bill’s abstract paintings in acrylic ink and gel pen. Husband and wife, this creative team has been improvising new work for decades, responding to first marks and finding a way forward toward a sense of completion in whatever medium they choose. In his dark paintings, the imagery comes forward from a black ground of permanent ink he lays down over the entire support. He removes the ink with an alcohol solution and then makes marks with fine-point white gel pens. Bill’s soul resides in the drawing, the almost microscopic-looking marks—thousands of them—that move in waves across the surface of each painting. In others he erodes the blackness into egg-shaped modules, like jostling cells, that form designs he doesn’t anticipate but discovers as he works.

Jean creates gelli prints building new textures of color with a brayer, and then she assembles portions these prints as a collage, along with found objects such as postage stamps or newsprint or columns of text or shreds of maps. In many of the pieces on view, she improvises her own imagined ancient script, which looks Middle Eastern. It’s quite persuasive, and on these faux Arabian lines she creates a sense of flow and assurance, like a master calligrapher’s brushwork. Jean told me she isn’t saying anything in particular in this automatic writing, simply channeling script in a tongue not yet defined. The work is playful and associative and brightly affirmative, dreamlike—the words sweet and spot serve as bookends for one images. It’s all essentially as improvised as her husband’s paintings. Her collages often look like disassembled and rearranged modernist mandalas, with north south east and west wings.

As a whole the entire show is introverted—in the sense, say, that Paul Klee’s paintings were introverted—and very understated. It’s quiet the way someone who would like to be heard speaks so softly you pay closer attention.

Flash Instant, acrylic Bill Santelli

I gathered with some other artist friends to talk about the show and our life as artists: Bill Stephens, Bill Santelli, Barron Naegel, and William Keyser. Stephens talked about how he works, but his process is instinctive and meditative; he doesn’t indulge in the kind of art-statement doubletalk that so many artists use to inject a bit of fuel into a career. We sat in a circle at one of the tables in the School of Art and Design in Booth Hall.

Stephens: I work with permanent acrylic ink, Caran D’ache crayon and white gel pen. I put down the black background and then remove it with alcohol wipes.The whole painting is done in black acrylic ink and I go in with 70 percent alcohol wipes and remove the ink to create shapes. The ovals are made using my finger. I pick up the texture of the canvas underneath. Then go back in with a fine point pen. White marker on top of the black. I had a young woman recently ask me, Mr. Stephens, when do you know when a painting is done? When I die, I’ll let you know that it’s done.

Santelli: How do you feel about where you are in your work?

Stephens: Good. I’m always experimenting. That’s all I’ve ever done. It’s coming together.

He keeps laughing after he says this, suggesting that his work is always coming together until he decides to keep working on it. We joked at one point that he should arrange with Jean to police his studio and remove everything that’s actually done, so he can’t keep finishing it. He told us that’s exactly how it works.

Stephens was explaining that he’s had a burst of creativity over the past year after a fallow period where he felt stuck, largely from physical ordeals. William Keyser arrived and joined the conversation, followed shortly by Barron Naegel from SUNY/FLCC.

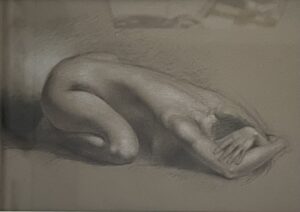

Figure drawing, Barron Naegel

Stephens: I finally came out of that fog I was in for a year. I think it was Covid. I had two bouts of it. And poison ivy. I had all the prednisone, two times. I was weed whacking and wiping my face with my hands. I was in the hospital for three days. I love this space. Not everybody does.

Keyser: I have a lot of colleagues here. I taught here 35 years. I have some associates who left and never set foot in the school again.

The discussion reflects on how school wasn’t an entirely pleasant experience for some artists. Santelli talks about brilliant young artists in school who just left art behind in their 20s. We discuss how art requires something more than talent and even brilliance, but a doggedness, a non-rational craving to see something finished a certain way. When I look at early Piero paintings, it’s hard to see any comparison to the astonishing work he did later in life where talent and skill were achievements hard-won over decades.

Santelli: Tom Insalaco had to fend for himself. He was a realist studying with abstractionists back in the 60s and 70s. Fred Lipp worked with Tom.

Keyser quotes, to a lot of laughter, what he thinks was Chuck Close about daily work: “If you are in your studio and something happens and it looks like art, it’s probably somebody else’s.”

Stephens: It’s very meditative because it’s early in the morning. It’s both connected (with the source of the work) and disconnected (from the rest of the day). I start with crayon, with a gesture and then go in with wash. I spend a lot of time sitting just working it out. It’s hard to put in words.

Dorsey: Don’t you see something emerge eventually, a figure in the foreground or something that appears?

Stephens: Yes. But it’s abstract. But as you’re going, you recognize something that gives you a structure. I’m always thinking of design. That’s what abstract painting is, it has to be a design. One step leads to another. It’s progressive. I never know until I get into it. One morning I discovered what I’ve been doing on many of these, wiping away the ink.

Santelli: I think Dave was referencing where you have another body of work where it can be really abstract but you look into it and a scene emerges.

Departure, Coming Home, acrylic,

Dorsey: The one of yours that I own. There are figures. (at right)

Stephens: It’s a ghost shape and then accentuated. It isn’t planned.

Dorsey: But as you are working those appear and then you build around them.

Stephens: Yes. Black acrylic ink on surface wiped away with alcohol wipes and then go in with fine-point gel pen and start to draw the lines.

Santelli: in this work you are taking away, excavating.

Stephens: Like etching.

Barron: I liked etching because it’s very process oriented. I would lay down an aquatint or whatever and get a pull from it and get nice results but if I would go to the next print it would disappear. When I was doing intaglio I loved it but the frustration was too much. I’d get a result that I wanted to keep. I couldn’t get it to last. It was this constant back and forth.

(The discussion really has more to do with Jean’s work on the walls, though nobody makes this point, the monoprints she makes and then assembles as a collage.)

Stephens: I don’t know what I’m doing until I do it. I don’t plan.

Dorsey: It’s completely open in the beginning and then the options narrow. You start to see what you are doing.

Santelli: I don’t think of my work as planned, just established by setting up the boundaries of what I will do. I was asking Tom when he was doing that big triptych we were talking about what he was doing. It had an abstract quality. He said, representational or abstract, it’s all about having a balanced composition in the end. I see this in your work as well.

Dorsey: But it’s more than balanced. Isn’t that just the base or foundation? With yours it’s more complicated than just a sense of balance with the colors. Maybe balancing warm against cool. It’s different from what you’re feeling when you put the colors down. It’s a melody, a sequence.

Santelli: Somebody might look at my work and think it doesn’t look balanced.

I ask Bill Keyser: Do you have a clear idea what you want to do at the start?

Keyser: I do have a clear idea. I long for the day when I don’t have to start with a pre-conceived idea but it hasn’t happened yet. Maybe it’s the result of working with materials that have a lot of resistance. Doing furniture for years I had an obligation to be faithful to the design I presented to the client. I always had a pretty firm idea before I started.

Dorsey: You had to. That’s function. Design and function are paired together there.

Keyser: I think I just OD’d on sawdust, making furniture. I took a painting class one semester after I stopped teaching and it was 360 degrees from where I had been before. It opened my eyes. You mentioned Fred Lipp. I thought he was a fantastic teacher. I ended up taking classes from him just before he passed away. About two years before he passed away. He had a fantastic eye. I don’t know if Insalaco ever admitted getting anything from Lipp or not. But from the time I was working with him I felt he could look at any genre of art and make a valid comment. He had little scraps of gray paper and he would come around the room and stop at your table and if you started talking he’d say just let me look and he’d take a scrap of paper and after a while he’d tear the right size and put it over an element of the painting and it was, wow, that’s where the problem is. I found that very helpful. After taking classes with him for a year and a half, I began to realize I was reliant on him. In the back of my mind I would think “I wonder what Fred would say.” I think that’s dangerous.

Bill Santelli pulled up, on his phone, a show of Keyser’s work from several years ago at the Burchfield Penney Art Center. It was stylistically coherent and of a piece, even though much of it was constructed around diverse found objects: but they orginated as detritus in the equivalent of a studio.

Bill Keyser, Fetch

Keyser: I had some combination glass and wood for the Burchfield Penney exhibition. A lot were found objects left over from other pieces.

Santelli: Was there less thought put in beforehand?

Keyser: I was more intuitive in that I was looking at what was laying on the floor in the studio and thinking “oh that’s interesting.”

My thought was that Keyser was essentially creating new work by building on what, in essence, was three-dimensional negative space left over from other work.

Keyser to Naegel: How long have you been at FLCC?

Naegel: 21 years.

Stephens, to laughter: God bless you.

Barron: It’s a mixed thing. We’ve had changes in the past five years under SUNY. Teaching to a mixed cohort of those who are present in class and those who are there remotely via streaming and those who just review the recordings and videos after the class. A number are coming back because they realize they have been missing out. But the administration wants to maintain the same model. The technology is there so that’s what we’re doing. We’ll have this extremely expensive high-end technology which may be grant funded, I don’t even know. Maybe it will just collect a lot of dust, if students keep insisting on coming back.

Keyser: I’m glad I was out before the pandemic. I can’t imagine trying to teach now.

Dorsey: They are trying to hang onto the cost savings the pandemic made possible.

Barron: It’s cost saving. This school, RIT, does not embrace that. If you attend and pay the tuition you want to be in a class with other people.

Keyser goes back to his thread of thought: the glass he used for the pieces in the Burchfield show was found. The rest was designed around it, so it was part serendipity and part planned.

Keyser: There was this company in Rochester that fabricates glass. High quality glass. They have a room with shelving where they stored left-over parts and rejects. I made an appointment and would go down and walk through this shelving. I found this detritus attractive. I designed wood elements around the things I selected. They were spontaneous but I looked at these elements doing a lot of cardboard mockups with a glue gun. Then I worked in wood.

Barron: I’m trying to work with the college on a bronze piece, working with students, which is challenging.

Bill: Jean and I are collaborating now. She’s taking some of my paintings and taking this cold wax and creating triptychs (by applying this

Jean Stephens from the show

layer of cold wax). It’s interesting to create something and to hand it over and say “whatever you do with this is fine.” She’s applying the wax over the entire painting. She’s using it for texture.

Keyser: I look at what you’re doing here as kind of a series. I’m envious. I can’t do that. I’m interested in how you can maintain a dynamic and spread it out over this number of pieces and have a cohesive series. You say there’s even more of these.

Stephens: I was going to say that what I’ve found out is that step by step doing the drawings first I have no intention of doing these paintings but it just morphed into that because I was at a standstill. I didn’t want to do any more drawings. I wanted to do paintings. So I figured out a way of painting some of the elements in what would have been drawings.

Keyser: In most of my work, though, in sculpture, there are individual ideas I get and then I do a sculpture and go on to something else. I’m kind of a fart in a windstorm. I’m all over the place.

Dorsey: You’re quoting Picasso right? (Scattered laughter.) I disagree. In the Burchfield Penney things there’s a stylistic uniformity from one to the next. That’s a series. You’re not even aware of your boundaries. You’re creating within a fixed set of esthetic rules, and they all look different to you but to us they look cohesive. You aren’t even aware of the boundaries you work within. It’s innate.

Santelli: Dave and I have talked about that a lot. In the beginning it helps to have these rules, but you don’t think of them as rules. You break them eventually. Like Churchill, if you find yourself in hell, you just keep going.

As we were talking, a young man came into the large main exhibition space, pulling a noisy rollerboard behind him as if he were coming in from the airport. He walked up to us and said to Stephens.

“I’m John, I don’t know if you remembrer me, I used to be your student I didn’t mean to interrupt. I’m just here for something. Good to see you.”

Stephens: Good to see you too!

The former student dragged his noisy rollerboard off into the Vignelli Center for Design Studies. It wasn’t clear what was in the suitcase.

Continuum continues through Dec. 14.

Comments are currently closed.