Larkin on Betjeman

I came across this opening to one of Philip Larkin’s essays at random when I spotted the collection on a shelf. He’s admiring John Betjeman for the limpid quality of his poems, their immediacy and accessibility, like the polymath conversational style of early W.H. Auden and James Merrill in The Changing Light at Sandover, a style that conveys an eagerness to be understood and a friendly sense of accessible humanity. He contrasts this kind of simple clarity with the work of T.S. Eliot, though Eliot’s The Journey of the Magi represents exactly the sort of poem Larkin loves:

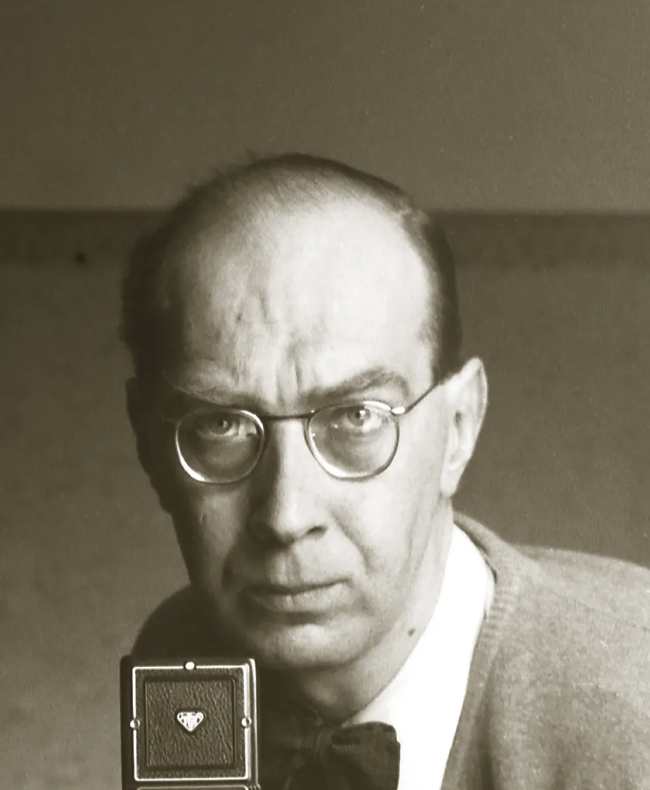

The scene is worthy of a nineteenth-century narrative painter: The Infant Betjeman Offers His Verses to the Young Eliot. For, leaving aside their respective poetic statures, it was Eliot who gave the modernist poetic movement its charter in the sentence, “Poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult.” And it was Betieman who, forty years later, was to bypass the whole light industry of exegesis that had grown up round his fatal phrase, and prove, like Kipling and Housman before him, that a direct relation with the reading public could be established by anyone prepared to be moving and memorable.

It strikes me as a passage that perfectly describes what I like in the work of most painters I love: the immediate sense of being shown something fresh and recognizable at some level, like a melody that instantly starts replaying itself in your brain. Creations that work without the need of interpretation, as Susan Sontag celebrated, because in the way they are painted, the artist conveys qualities equivalent to those conveyed by an individual’s facial expressions, body language, bearing, way of speaking . . . in other words the entirety of a single human wholeness expressed in all the little parts. But the quote also points back to a time when painting didn’t require an instruction manual or a critic to do its work. That time is still now for most painters I love.

Comments are currently closed.