Nativity

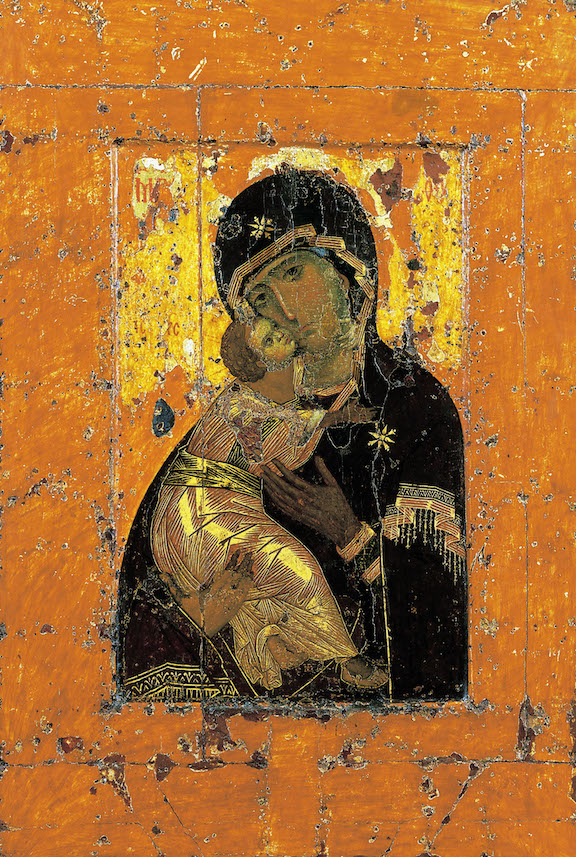

Theotokos of Vladimir, 11-12th century Constantinople, egg tempera, 27 x 41

From the Old Jordanville Prayer Book:

Rejoice, height inaccessible to human thought.

Rejoice, dawn of the mystic day.

Rejoice, rock that refreshes those thirsting for life.

Rejoice, door of solemn mystery.

Rejoice, thou who shows philosophers to be fools.

Rejoice, thou who exposes the learned as irrational.

Rejoice, ray of the noetic Sun.

Rejoice, thou through whom creation is renewed.

–Excerpts from the Akathist to the Theotokos

These lines, in an oblique way, express–in a more ecstatic mode–how I’ve responded to much visual art since my teens. It’s hard to imagine how something in this spirit could be sung as an accompaniment to paintings being made now. Where are the mysterious painters who might evoke this sort of mystical affirmation? Some modernists would have recognized something like this as the mission for painting, Klee and Chagall, even Kandinsky, and many others. Some of the modernist writers as well, Proust and Flaubert (if you look at the arc of his subject matter over his career) and Eliot and Auden.

The Old Jordanville Prayer Book is named after a Russian Orthodox monastery south of Utica, New York, a place I visited in the 80s, a period when I was studying print-making at Munson-Williams-Proctor and writing for the Utica newspapers. When we lived in Utica, I saw a retrospective of Charles Burchfield paintings at the museum that had a deep effect on me, as well as a survey of contemporary representational art that opened up my sense of the possibilities available to me as a painter. When I was assigned a feature story on the Jordanville monastery, the spiritual energy I discovered there astonished me. What most impressed me was how the monks were busy publishing literature to be smuggled into the Soviet Union, before it fell apart, when that country was most repressive, harassing and persecuting its own Orthodox practitioners. Russia maintained tight censorship over religious publications, so the role of producing and distributing books, as samizdat, that Christians wanted within Russia’s borders, fell to a little organization in upstate New York, Holy Trinity Monastery. My visit there bolstered my interest in and respect for Russian Orthodoxy which began in college when I read J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey and then The Way of the Pilgrim, probably the best-known book associated with this church. Now, years later, after having read Everyday Saints–stories about monks in the Soviet Union when the regime was actively hostile to their faith–I found Russian Orthodox services only miles from where I live, in Brighton, NY, at the Protection of the Mother of God. It’s a beautiful place to try and quietly contemplate the ultimate reality of life with people more meek and humble than I am, while being surrounded by paintings on nearly every square inch of wall and ceiling, which seems a particularly appropriate haven for a visual artist to keep an eye on his own spiritual health. One of my good friends at the church, Father Theophan, a Danish monk from Holy Trinity, lives in Brighton–more or less on assignment from Jordanville to assist the church–paints icons, and is also translating the Psalms into Danish from Greek and original versions in other languages. His path began when he read The Way of the Pilgrim around the same age as when I read it–and he likewise became both a painter and writer. At some point, I hope to do a post about him. I’m fascinated by how icon painting is an ongoing and mostly overlooked niche of the art world, continuing without any expectation of economic reward or critical recognition.

I write this post in memory of Peter Shehldahl, The New Yorker’s art critic who confessed to being a non-church-going Christian when he knew he was terminally ill, not long before he died in October. His intelligence and humanity lives on in his writing.

Comments are currently closed.