The Raft of the Painter

Tribute #2, Tom Insalaco

Tom Insalaco is a bit of a phantom. After six decades of making art, this award-winning painter continues to create new art every day, but he makes little additional effort to prove that he exists. In a world where social media has become the latest addictive drug and the new hothouse for growing a career, he shuns publicity and refuses to promote himself. A Google search turns up almost nothing about him, except for the samples of his work at Oxford Gallery’s website. He has no website of his own. He has a Gmail address, but insists that he doesn’t know how to use it. At midnight, sometimes, he steals onto the Internet but leaves everything as he found it. He watches art documentaries on YouTube or Netflix, or clicks around to discover another contemporary painter to admire or to see what’s happening at his favorite Manhattan galleries, but he signs off without leaving a public trail. Though he’s as prolific as ever, the Internet has yet to recognize his existence—which means almost no one has access to his five decades of work.[1]

At the age of 75, he rarely enters exhibitions though for decades he has been repeatedly invited into the Memorial Art Gallery’s biennial Rochester/Finger Lakes Exhibition, widely considered the most prestigious show for visual artists throughout New York State west of the Catskills. More often than not, he wins one of the exhibition’s awards. Not long ago, he contacted that museum and asked how many times he had been included in the Finger Lakes show. (He doesn’t keep count of his honors.) He was put on hold for a bit, and the woman returned with a note of surprise in her voice, telling him that he was the single most exhibited artist in the exhibition’s history. His first inclusion was back when he was in graduate school at Rochester Institute of Technology in 1969. Since that phone call, he hasn’t heard from anyone at MAG suggesting maybe it’s time to offer the public a long-overdue Insalaco retrospective. He remains mostly under the radar because he’s too busy making art to worry about whether or not anyone sees it.

His exhibitions have been few and far between, but they have been distinguished. He achieved modest regional fame throughout the state after he completed his monumental Tribute Triptych in the early 90s in reaction to the random murder of his brother. A show was initially organized around it by Finger Lakes Community College, Gallery 1100 in Buffalo and Alfred University. By entering each of these three large paintings serially into different Rochester Finger Lakes exhibitions, he won the top prize three shows in a row. In 1995, the same triptych was the centerpiece of his contribution to a three-artist show along with William Stanley Taft, Jr. and Jerome Witkin. The show featured Witkin’s suite of paintings about Buchenwald alongside Insalaco’s work. In 1996, the triptych made its way into the New York State Biennial at the New York State Museum—participating museums included Albright-Knox, Brooklyn Museum, Memorial Art Gallery, Munson-Williams-Proctor, Queens Museum of Art, and College Art Gallery at SUNY New Paltz. Insalaco’s paintings were shown with work by a small selection of artists from around the state, including Joy Taylor, Stephen Assael, George Wexler, Elizabeth Olbert, and Phil Lonergan. His paintings have also been shown at Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse and the Butler Institute of Art in Ohio, which owns his work. After he retired from a 30-year career of teaching at SUNY/Finger Lakes Community College, the school named its art gallery after him, along with his fellow professor and close friend, sculptor Wayne Williams, who founded the school’s art program along with Insalaco in 1969.

Yet these honors have been rare, partly because Insalaco shuns the art world. He views it with irascible skepticism, casting a gimlet eye on much of what passes for visual art in the 21st century. He paints like an Old Master, without any required postmodern irony to make his antiquated methods feel contemporary. Once upon a time, he worked with great skill as a photo-realist in the wake of that movement’s emergence in the 70s. It was directly after this, in his middle period, as it were, that he constructed vivid visions of his own inner life, painstakingly detailed and realistic, both surreal and Baroque, a visual truce between the 20th and the 17th century. His Tribute Triptych, 104” x 248,” marked this leap forward in his work. At the time, these paintings drew the interest of both curators and critics across the state. Insalaco was poised to become far more widely known. But since then, he withdrew and continued to work mostly out of view. He still paints daily, by artificial light—all windows shuttered or curtained—chasing the glow of Rembrandt, Rubens, and Caravaggio, for the most part, still trying to make mysteries visible, but in a less epic way than in the past.

2

Insalaco isn’t a reactionary. He loves and admires much modern and contemporary art. He regularly books a room in Manhattan and tours both the museums and the galleries, sometimes putting in a week to absorb what he needs to see. In his own idiosyncratic way, he cherry-picks his favorites from the last and current century: Olitski and Thiebaud, Dali and the Futurists, dozens of representational painters like Daniel Sprick, Adam Miller, Odd Nerdrum, Vincent Desiderio, Chuck Close, Jenny Saville, and Francis Bacon all make the cut, to name only a few. But he dismisses vast regions of contemporary art with a sneer and refuses to read most of what’s written about it. Insalaco despises most art-speak. To him, it’s just inside baseball among the initiated who have little interest in reaching anyone outside their coterie—either through the work or the theory that gives rise to it. Camille Paglia has a characteristically impertinent but credible theory that the rise of postmodernism and the French deconstructionists in the 70s was a response to the dying job market for academics: it became the secret handshake among those who ended up employing fellow members of this emerging intellectual orthodoxy. If you were a part of the club, you got one of the rare available jobs. It was an arbitrary way to thin the herd. That’s her scornful take on the origins of the intellectual movement that continues to shape how universities teach the humanities.

Whatever else postmodernism has done, for good or ill, it has shut out most people from a passionate interest in what’s produced under its influence. The problem for a practicing artist is essentially that visual art has distanced itself from ordinary people, so most of what’s written about it survives at that same lofty altitude, addressed to the niche of people who care about the subject, no matter how it’s written. As a consequence, most people don’t find much to identify with in what’s happening up in that rarefied air, where art gets the most attention and is sold for the highest prices. They have a sense that the art world intentionally excludes those who haven’t been initiated into its practices. In parallel, the art market addresses itself mostly to the richest of the rich. As a result, visual art has become less and less central in the lives of most people. Theory and practice have both tended to isolate visual art over the past six or seven decades even more than in the past.

Though it has always been an elite activity, before the advent of modernism painting was accessible to nearly anyone who wanted to enjoy it. You didn’t need a college degree to take immediate pleasure in a Chardin still life or a Franz Hals portrait. In the early days of modernism, this still held true: Impressionism was an outrage at first but quickly became easy to love and thus easy to hate by the intellectuals. Now the international art world seems to thrive as a kind of gated intellectual community, happy to live behind the walls of its moneyed compound, a world indifferent to those who aren’t entering it via the usual MFA tributaries or flying to the Venice Biennial on their own private jet. Most people are more than willing to buy a ticket to another Van Gogh or Vermeer retrospective but remain utterly baffled and annoyed by Matthew Barney.

That’s the world as Insalaco sees it. He remains happily insulated from all of this, partly by choice and partly because he hasn’t been invited into the compound. It has no bearing on what he does. He ignores most of what’s happening inside those gates, and it returns the favor. He has given up on everything but the next brushstroke. Insalaco was once turned down for a solo exhibition, and he suspected that it was because, in the application he didn’t elaborate on why his work was “socially relevant.” Koons can be made acceptable, in this vein, not because he’s an expert purveyor of amusing and beautiful Pop baubles. It’s permissible to respect him if you see his entire mini-industry as a cynical attempt to embody and lay bare the money-besotted rot of the art world itself. When postmodernism embraced a watered-down Marxist critique of Western culture, it spawned the notion that for art to remain vital it had to be rooted in an anti-establishment political and economic critique—a censorious, bitter version of the anti-establishment, consciousness-expanding politics of the Sixties. As Paglia puts it, blowing one’s mind morphed into: Capitalism bad. Identity politics good. Anything that recognizes value in traditional Western culture, now under fire from the entrenched neo-Marxists, is unacceptable.

What does this have to do with Insalaco? His work recurrently draws from Biblical myths for it’s subject matter, sometimes with irony, sometimes not. One of the simplistic offshoots of the current orthodoxy is the view that the notion of God and the myths of religion are embraced mostly by Bible-thumping, simple-minded racists with an arsenal of guns and an opposition to gay marriage. One doesn’t hear nearly as much about how the values embodied in the Torah and the Gospels track across cultures and resonate with the wisdom of the Upanishads, the Koran or the Buddhist sutras. Religion is either superstition or a tool for someone somewhere to exploit and extract obedience and wealth from the opiated masses. That’s the core postmodern critique, applied mostly to the Western canon in order to discredit “the patriarchy.”

Insalaco has no stake in that battle. He wants no part of the postmodern prison that rejects the notion of universal truths rooted in psychological or spiritual mysteries. What was true for the Greeks is true now—beauty and goodness and truth are as “relevant” now as they were then, with or without any signifiers about contemporary society. (The postmodern left has suddenly embraced the notion of objective, incontrovertible truth with a vengeance now that Washington, D.C. seems to have embraced a disregard for factual accuracy. When truth becomes inconvenient, then it will be abandoned again.) What was true for Donatello is just as true now. Painting, for Insalaco, is about the human condition, our mortal predicament, which is now as it was at the dawn of the species. Nothing essential has changed. We live and we die and it torments us that we don’t know why—though now and then we get rare hints of something true and beautiful behind this veil of confusion, an intimation of transcendence and real freedom. That’s Insalaco’s subject: our confusion, as well as those fleeting intimations of inexhaustible beauty.

It should be no surprise that one of Insalaco’s favorite words is bullshit. Not long ago, he visited the Whitney and literally shouted an obscenity or two, startling the guards, when he came across a room partly filled with mud. It was in fact almost the perfect visualization, on a massive scale, of his favorite single-word invective when talking about the art world—by shouting it aloud, he was essentially offering a pithy, alternative interpretation for the installation itself. Even a postmodernist might have admired that one-word deconstruction of the work—it was certainly visually descriptive. It was also a declaration of why he refuses to play the game.

Well into his eighth decade, he continues to paint as purposefully and tirelessly as he did in his youth, working as hard as anyone young and eager enough to climb the art status ladder with a studio in Brooklyn. He ignores the fragmentation of art into our current Heinz-like multiplicity of genres and methods and sticks to paint, working every day in his own humble-proud way, with immense energy and focus. He lives in a Depression-era two-story house in the Finger Lakes, in the town of Canandaigua, where he gets up in the morning, brews a cup of espresso, and works on a new drawing—a drawing per day is his target—in the upstairs apartment where he cooks, eats, sleeps, reads and watches an occasional movie. After a few hours, he moves downstairs and spends the rest of his day at his easel.

He shuns publicity and self-promotion, but he’s no recluse. Sometimes he shares a meal with his partner and fellow painter, Debra Stewart, who lives an hour away in Rochester—and he regularly meets with other regional artists for coffee and conversation. His upstairs living quarters have the square footage of a modest three-room flat, with the largest room divided into living area and kitchen. When he moves downstairs to his small painting studio, he makes his way through a warren of dimly-lit rooms, some turned into storage, choked with finished paintings, lumber, tools, objects of furniture buried under mounds of gear, art supplies, and all the detritus generated by the tunnel-vision intensity of his painting practice. Tucked away in these rooms are amazing, large-scale, decades-old paintings. He finishes a new painting, finds a place to store it and moves on to the next one. He has no time to organize his own past, to make sense of any of it or convince anyone else to exhibit his work. Jim Hall shows his paintings regularly at Oxford Gallery but never sells them, because Insalaco won’t price the work to appease the budget of regional collectors. He will sell a painting only for what he thinks it’s worth. In his view, it isn’t his problem that others don’t want to pay that much—though, on his side, Hall might wish for a price point slightly better suited to balance his supply of Insalaco’s paintings with the demand for them. Insalaco doesn’t keep an eye on sales. His job is to make art, not to make it acceptable.

3

He was born in Buffalo and grew up in a working-class Italian family on the city’s west side. His mother raised her seven boys while his father worked two jobs to support them all, first in construction and then for Allied Chemical, a firm that allowed him to work for 29 years before laying him off, just before the anniversary that would have entitled him to a full pension. Insalaco was raised Catholic. He continues to rely on the universality of Biblical themes for many of his paintings, but he doesn’t think highly of organized religion, or any institutions, for that matter. He’s not a joiner. It’s the depth and inexhaustible mystery of the Biblical myths that draw him back again and again—not the organizations built around them.

He began drawing at the age of six and began painting in grammar school. One of his high school teachers recognized the promise in his work and secretly emptied out a storage room at the high school in order to equip it as a studio for Insalaco. It was filled, floor to ceiling, with art supplies, thanks to this teacher. No other student was allowed to use it. There was no dubious quid pro quo required by this surreptitious act of patronage. The teacher wanted nothing but the reward of nurturing the young man’s talent. It was a bit of a confederacy—a game to get away with something worthwhile. At the same time, Insalaco was turning into a bit of a player. He told the school’s administration that he had to work every afternoon to help his father support their large family—true enough—but he didn’t tell them that his job started late in the afternoon. So he finagled permission to attend classes only until noon, which gave him multiple luxurious hours in which to paint in his private, improvised studio. He felt like a king. And from that point on, fueled by the generosity of that one teacher’s recognition and support, Insalaco committed himself to painting.

In school, he was reserved, observant, and skeptical of the various cliques that might have been open for membership. He thought about playing football, but realized after a few scrimmages that the sportsmanship of the game seemed to rest on a suppressed urge to actually kill the opposing lineman, or at least disable him. So that particular club wasn’t for him. He saw the hipsters and toughs on the street corner as just another member’s only club, with their own exclusive cool. He watched them from a distance long enough to realize they would likely end up as druggies, drop-outs and failures. Most of his fellow students were from Buffalo’s working class, but in the Sixties, many of them came from wealthier zip codes, wore blazers to class and raised their hands to ask a question. He decided he was going to learn enough to have a chance at being more like one of the blue blazers, not the guys twisting a cigarette butt into the sidewalk under a boot heel. He wanted to make more of himself than many of the kids who came from his own neighborhood. He started taking art seriously, mostly by studying the work of others and getting better on his own time. By the time he graduated from high school, still 17 years old, he locked himself into his parent’s house all summer—while the rest of the family was away in Canada—and he did nothing but paint. He ignored the telephone, never once answered the front door. He tried one thing after another, experimenting, searching for a way to balance his love for both abstraction and representation—as most great painters do, to one degree or another—discovering mostly what didn’t work, but occasionally what did.

Not sure he could afford college, he applied anyway, tentatively hoping to get at least an associate’s degree at Buffalo State Teacher’s College. His academic record was fine, but not stellar, and in order to get in, he had to undergo a portfolio review with a photography professor. The interview didn’t seem promising until the professor asked what Tom happened to be reading that summer. He said Catcher in the Rye and Leonard Feather’s History of Jazz. With a stunned look, the advisor laughed out loud and said, “I’m reading the same two books.” That little moment of synchronicity got him into the program for a degree in art education. Toward the end of the two years, he was told he had to take a class in basket weaving and another in community planning. “I told them I’m not doing that. What the hell are you talking about? That has nothing to do with art. I’m here to learn painting and drawing.” In anger, he dropped out, just short of earning his two-year degree.

For a couple years he worked as a laborer, loading lumber into boxcars and accepting whatever other work he could get to make money and save a bit, hoping to enroll at SUNY/University at Buffalo. He was admitted into the school, but because he had dropped out before finishing his degree, he was unable to carry over any of the credits he’d earned. He was demoted back to the rank of freshman. Two months later, in the middle of a class, an administrator came through the door and said, “Is Tom Insalaco here?” His heart skipped. What had he done wrong now? He timidly raised his hand. “You’re no longer a freshman. You’re a junior. Come see me later and I’ll explain.” Someone had pulled strings and ensured the transfer of his credits from the previous program. Again and again, throughout his life, other people—recognizing his remarkable promise—took it upon themselves to reach out and help him. It’s a good thing, because he’s never promoted himself, almost to a fault.

4

Insalaco is ambivalent about most of his education. What is often true now was true half a century ago: there was too much intellectualizing and not enough craftsmanship. He had little advice on how to make a painting, what mediums to use, and how much, what supports, how to mix paint properly, and all the other secrets of how to make paint do things few people can make it do. He once asked a professor how to create skin tones and the response: “How the hell should I know?” In other words, even then art school was more about ideas than execution.

Painting is a physical skill, in which truth emerges through a bodily act rooted in an evolving perception—the ability to see something mysteriously good materializing through the act of painting itself and then struggling to nurture it, like a growing plant, as the painting reaches completion. It’s a continuously frustrating wrestling match between what you see emerging on the canvas and what you want to see instead—and it’s rooted in the basics of color, composition, light, and a quality of line. All the ideas that cluster around that emerging vision come afterward, not before—even though the postmodern agenda completely reverses this order: you figure out what you want to “say” and then illustrate it. It’s interesting to compare Insalaco’s paintings to Witkin’s Holocaust paintings, which once hung on adjacent walls: Isalaco’s are impossible to scan and parse, continuously suggesting contradictory things about art and life, as elusive and full of resonance as music, while Witkin’s are unambiguous, forceful depictions of human cruelty. Insalaco was finding subconscious correspondences in completely unrelated things, cherubs and bellhops, masques and murder. Witkin’s paintings are as much about the act of painting as Insalaco’s, but Witkin makes it visible in the energy of his brushstrokes, whereas in Isalaco’s triptych it’s depicted narratively through self-portraiture, showing the artist himself at work surrounded by his influences. Witkin knew what he wanted to say. Insalaco produced work to make visible his own doubts and faith in ways that are impossible to see as a clear, definitive statement about life.

“What did I learn in school? Practically nothing,” he says. “It sounds arrogant, but I learned this and that but when it came to painting, my main teacher was an abstractionist who didn’t have a degree so we spent a lot of time talking esthetics and theory. He was very perceptive. In retrospect he was trying to make up for his lack of a degree. But he was really good. I just didn’t learn much from him. I learned mostly from my fellow students, in the studio.”

During his senior year, in September of 1967, Insalaco was drafted into the Vietnam War. He hated the fact that America was fighting a war based on the assumption that Communism would spread across the Pacific toppling free societies like dominos. Insalaco didn’t want to kill anyone in order to defend a 17th parallel thousands of miles away. He went to the draft board with his father and in the first five minutes of his interview, he told the officer that he would rather kill him than any Vietnamese citizen. This didn’t sit well with the leatherneck across the desk. Insalaco promptly got up and left, leaving his father to make amends. The next day, he climbed into his TR4 and drove across the continent to San Francisco in three days, with thirteen hours per day on the road. He found a place to crash and looked for a way to make money, intent not just on fleeing the draft, but opening a new chapter in his work. He tracked down Davis Cone and struck up a quick friendship. Cone introduced him to Robert Bechtel and would have done the same with David Park and even Diebenkorn, but two weeks later Insalaco’s father called and said he’d hired an attorney. The lawyer had straightened things out with the draft board, pointing out that his college enrollment exempted him from service. The Selective Service happily forgot about him, after that. So he came home.

By 1968, he was graduated with a B.A. and promptly went back to work as a laborer, driving trucks and loading boxcars again. And again, someone else pointed him toward his future: his younger brother, who was also majoring in art, joined him for dinner. During the meal, he told Insalaco that Rochester Institute of Technology was looking for graduate students. Interviewers were coming to Buffalo to reach out to people interested in getting an MFA. His brother had no interest in continuing with art; he wanted to go into business and make money, which he eventually did. But Tom figured he ought to give RIT a chance. By the time he interviewed, he had been substitute teaching in the Buffalo school system, even while keeping his second and third jobs as a laborer. The young advisor from RIT asked, “You’re doing all this work while you’re teaching?” Impressed, he recommended Insalaco for a fellowship, so he was able to earn his advanced degree in a year, with a stipend for expenses and a waived tuition. Again, he learned more from his colleagues in the studio than he did from his professors, as they all experimented and explored different ways to paint, sharing discoveries.

He accepted a semester internship at Finger Lakes Community College, and began teaching a class in art history, though he was only a couple weeks ahead of his students in the subject. He devoured the textbook and did supplementary reading, cramming for his lectures a few days ahead of them, the way students did for tests. In the process, he developed a complete set of lesson plans that first year and then settled comfortably into the teaching routine in succeeding years, as an adjunct. Again, someone else stepped in to show him a path forward. One of his students, a young woman who had been especially bright in class, went on to enroll at SUNY Geneseo. When she began another course in art history there, the professor called her aside and asked her how she had become so astute in the subject. She said: “I took a great course from Tom Insalaco at FLCC.” The professor was so impressed by how much she knew that he went to the trouble to write a letter to the FLCC president praising Insalaco’s skills in the classroom. Someone else was turning the key to open a door toward his future: he was hired as a full-time faculty member in 1972 and stayed at the college until his retirement three decades later.

He was a natural at teaching. Though he could come off as stern and intimidating to many of his students, he worked with them on their terms, and they felt engaged because he listened and actually learned from them. Bill Santelli, a Rochester abstractionist, says he learned how to paint from Insalaco, who had no interest himself in painting that way: “Tom has been such a huge influence on me. I might have been a failure if not for his example.” His reputation became so great within the region, more than a dozen people from Rochester, painters with some success already and who had already earned four-year degrees, sought him out at his community college and enrolled in his studio classes. Once the Memorial Art Gallery called him to ask permission to put his house on a tour of regional artist studios. The idea is almost comical considering Insalaco’s craving for privacy and isolation. Tom ended the conversation with a peremptory and curt no, which might be why he hasn’t heard much from the Memorial Art Gallery since then. The reality is that there was no way, logistically, to herd a busload of art lovers through Tom’s home studio. It’s mostly storage for decades of work that hasn’t sold.

5

If you climb the staircase up to what is essentially a two-bedroom apartment on Insalaco’s his second floor, you come to a landing and a turn into a little hall that leads both to his bedroom and his kitchen. In this little balcony two large canvases from his days as a photo-realist cover most of the walls. They’re perfectly realized with a deep appreciation for the feel of the painted mark—the quality of the surface is as lovingly crafted as the illusions they conjure up. In one, a brightly lit scene shows several tourists, from behind, gazing over a guardrail at Niagara Falls. Hanging beside it, in view as you climb the stairs, is a large interior/still life in a mode reminiscent of early James Valerio without quite Valerio’s level of nano-detail. It’s called Georgia’s Stuff, and it appears to be a loving glimpse at the jumble of clothing and gear his new girlfriend had piled onto a little table in his apartment when she arrived. Everything is rendered with just enough precision—not the current high definition of contemporary hyperrealism. On one side he shows a large potted philodendron xanadu and back near the wall, the brown plastic dust cover for an old Garrard turntable. Light from a side window casts distinct pools of shadow to the left, and the cascade of random fabric tumbles forward with tactile luxuriance. Aldous Huxley, who studied Western painting while high on mescaline, speculated that painting’s greatest power was to represent infinite variations of clothing. Fabric on fabric. He found the shapes and colors and patterns of clothing full of inexpressible meaning. Huxley would have loved this canvas.

Civilized human beings wear clothes, therefore there can be no portraiture, no mythological or historical story-telling without representation of folded textiles. But though it may account for the origins, mere tailoring can never explain the luxuriant development of drapery as a major theme of the plastic arts. When you paint or carve drapery, you are painting and carving forms, which, for all practical purposes, are non-representational . . .[2]

Huxley succinctly expressed why Isalaco’s painting is so satisfying. It’s a precise and complex evocation of a single, fleeting moment in Insalaco’s personal life—your eyes can almost feel the texture of the folded corduroys and the plaid flannel sleeves. Yet it’s also a complex, dissonant assembly of shapes and patterns that work as a flat composition, a jazz solo.

Turn the corner into his kitchen and living space, you’ll probably first see his homage to Chuck Close, two enlarged close-up portraits of his aged parents. It’s a diptych he turned into a triptych this year with a self-portrait of exactly the same scale—four feet by four feet—so that when the three paintings are exhibited his face will appear between those of his father and mother. Again, the technique is photo-realistic with every wrinkle and highlight and flaw carefully reproduced in the faces of his mother and father.

These decades-old paintings are the work of a master painter only a decade out of grad school. He could have continued on this path indefinitely, finding new visual realms to explore in this mode, while easily reaching a receptive commercial market in Manhattan at one of the galleries that trade in contemporary realists and photo-realists. But his work took a darker, more introspective and idiosyncratic turn after his brother, Robert, was murdered.

Insalaco remembers the exact moment when his life and his work changed utterly, as W.B. Yeats put it. He recalls:

I was teaching summer school with fall off, planning on at trip to Italy to study Caravaggio’s work. It was the last day of class, the last ten minutes, actually, and a couple of people came up to invite me for a drink at Lincoln Hill. A phone rings in my office, and picking it up was the last thing I did that day at school. It was my brother, Dennis, telling me Robert had died. That’s when I began to conceptualize the trilogy. Finishing it, in four years of work, was when I really became a painter. It was really quite a revelation to understand what it takes to do something of that scope.

At 2 p.m. Aug. 13, 1987, Erie County Sheriff’s Deputy Robert Insalaco showed up at the front door of a home in North Collins to arrest the man who lived there on a warrant for outstanding felony criminal mischief. Insalaco’s brother rang the bell, but as the suspect opened the door, completely naked, he shot and killed the 43-year-old deputy with a .44 caliber pistol. The tragedy was even more crushing because the killer’s own son had died not long before in the bombing of the U.S. embassy in Beirut—the father had gone mad with grief. Previously, he’d attempted to set his own garage on fire. The death plunged Insalaco into a period of desperate brooding. His had a loving, close family, and the wound of that loss refused to heal.

But after only a short interval, his despondency gave way to a defiant and sustained burst of creative energy. All of his talents seemed to mature at once along with an assurance about what he wanted to achieve. Over the next four years, he worked on the three linked paintings, the largest canvases he’d ever completed—vastly exceeding what he’d been doing up to that point in both imaginative scope. The triptych works as an elegy for his slain brother, an affirmation of the moral struggle inherent in visual art, and a suggestion that painting can serve as a spiritual life raft, an ark, for those who make it as well as those who love it.

6

If you read the Tribute Trilogy from left to right, the paintings seem to have been completed in reverse order. They are all named Dedication, and appropriately enough, each comes with its own short epigraph: To all those who have lost their lives at the hands of madmen and fools. Somewhere in the world the sun is always shining. Man’s final resting place is in the hearts and minds of other men.

The last to be completed is the most dramatic and arresting: it shows a group of men and women lifting the lifeless body of Insalaco’s up toward a pair of Baroque angels emerging from a vortex in the sky. Everything is only partly revealed by a spotlight from above, the circle of human figures like a mosh pit strenuously holding Robert’s limp figure aloft. A blood-red sunset serves as backdrop. Insalaco himself sits in the foreground gazing toward the ground, in almost the same pose and mood as Durer’s angel in Melancholy. His parents stand to one side, not able to look at the offering of their son—which seems more pagan human sacrifice than some sort of physical ascension into heaven. Insalaco’s surviving brother, Dennis, stands behind the parents, and behind him, Peter Berg, a brilliant Rochester realist painter and teacher who also died prematurely. As you look at it, though, the whole thing appears to be presented as a performance, a stage play: though the backdrop could be an actual seascape, at the edge of a calm ocean, the bloody sky almost seems to be painted on a canvas hanging behind the figures, which makes the lighting look even more theatrical. At the bottom edge of the image, a skeletal hand reaches up toward an hourglass—a very Renaissance symbolic gesture.

The painting makes a stunning impression, not only because of its content, but in the simple way the painter structured the diverse figures into one unit, building a composition in which everything in the picture pivots around the head of his brother, which is nearly hidden from view. It’s slightly reminiscent of David’s Oath of the Horatii, in which all of the raised arms unite into one purpose, soldiers in the middle and mourners off to the right. But in a counter-intuitive way, much of the power in this painting is entirely sensuous. The way he captures, once again, the folds and textures and feel of the casual clothing, the t-shirts and jeans, as well as the wonderfully rendered arms and hands, helps convey the weight and burden of the collective struggle—it makes the entire image immediate, palpable and oddly familiar. The painting also suggests Sisyphean defiance in the midst of hopelessness—raising the body up only to find that a mere angel can’t do anything but cast the orange shadow of his splayed fingers on Robert’s face. Everything is poised at that uncertain moment of truth when the dead brother will be lifted up supernaturally or else become too heavy for human arms and drop back to earth. Despite the darkness of the scene, no one here is succumbing to despair, though the immediate family is immobilized by the death.

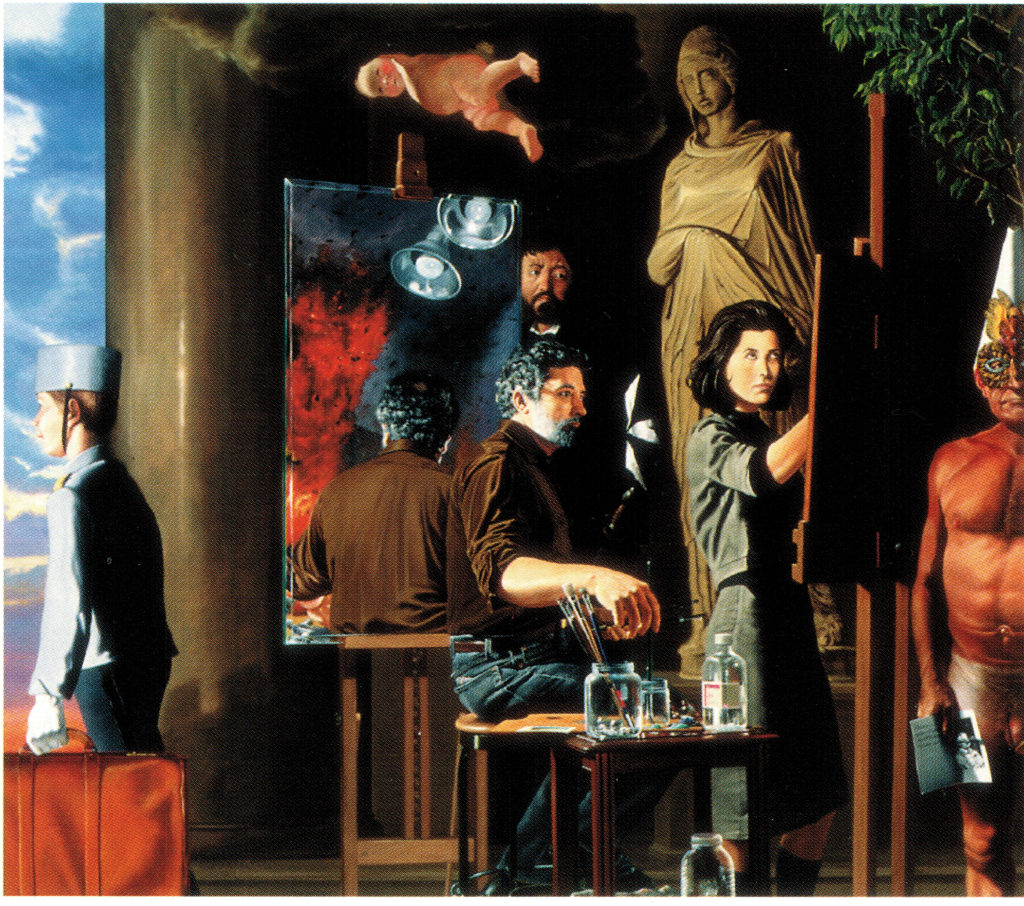

In the next, the central painting, Insalaco broke through some internal barrier and created the most fascinating and inscrutable painting of his career. It’s a menagerie of diverse, seemingly unrelated figures and objects, assembled as they might be in a lyric by a surrealist poet. He had personal reasons for putting every detail into this painting, but the painting exceeds the intentions that drove him to cobble these figures together. It has the hallucinatory intensity of a lucid dream, disorienting and disquieting, yet it’s the most satisfying painting out of everything Insalaco has done. For all its weirdness, it’s almost placid and serene, and orderly, lit by natural light flooding into the scene from a huge portico on the left that discloses a vertical strip of lovely blue sky, streaked with cirrus clouds. The painter sits as an instructor or admirer of a female painter working at her easel, while to the right of the couple stands a macabre reveler, naked, with tan lines above and below the pale stripe of flesh at his exposed crotch, presumably skin once shaded by discarded swim trunks. He wears a dunce cap that has been modified into a mask. Though it’s a portrait of Robert’s naked killer, transposed into the reverie of the picture, he looks like a dazed refugee from a debauched Venetian masquerade, a precursor some bit player in Eyes Wide Shut. Opposite, departing the canvas on the left, is a wonderfully realized bellhop, in pale blue with his own cylindrical blue hat, full of crisp energy and purpose, carrying a tan leather valise. In the background, looming over Insalaco and his student, a tall Romanesque statue gazes down on the room, her hand raised up beneath her robe. And behind the painter, on a second easel, a beveled mirror reflects a glimpse of the infernal fire that seems to light up the sky in the triptych’s flanking paintings—the killer’s burning garage, or a glimpse of hell, or both. At the top floats a perfectly rendered pink cherub, a Renaissance putto with a doll-like face. He bobs like a helium balloon in soft, enveloping billows of smoke rather than clouds.

The painting somehow makes all of this phantasmagoria look commonplace and casual as if a nudist Mardi Gras is always happening next door, and Ritz-Carlton bellhops with white gloves from the fifties are ready to hump your bags out to your parked Subaru. Off stage, there are those hellish cinders blossoming in a column of red, throbbing in view of the seated Insalaco, just outside the left edge of the painting, but you only notice them in the reflection behind him. They’re far enough away to have little impact on the art lesson in view. Behind them all, Caravaggio himself gazes down, benignly, approvingly, pleased.

It’s a perfect balance of the light and the dark, the precision of everything, down to the jars full of brushes and solvent, and it makes you want to dwell on the painting again and again, no matter how familiar it gets.

The third painting, on the right and the first one to be complete, is built around the suggestion that art can serve as a life-preserver for its practitioner and maybe its viewer. In the foreground, gazing directly at the viewer with a brush in his hand and a small palette, Insalaco stands before an easel bearing a blank canvas. Beside him is a small table, with a still life arranged around a human skull, an article about his brother’s death, a framed photograph of his brother and a crucifix. The crucifix hung on the wall of Tom’s childhood bedroom, where he and Robert slept in the same bed—small house, large family—because they were born only sixteen months apart.

Behind this ordinary studio scene looms a much larger canvas on which is painted a detail from The Raft of the Medusa, including the two figures waving articles of clothing—more fabric—to catch the attention of the ship on the horizon, which is not in view. An angel in the upper left corner reclines on a cloud cushion to get a look at the Gericault study. Finally behind that second painting you can glimpse another surviving Insalaco brother with folded arms and bowed head, next to an American flag, presumably from Robert’s funeral, and a dark, barely visible likeness of Robert himself behind that, standing at attention, wearing his campaign hat. The clouds in the distance, behind everything, are again red. Aside from the complicated themes of personal loss, mortality, spiritual torment, and the hope for salvation, the series is almost as much about Tom and the history of painting, how talent and understanding get handed down from one artist to the next, from Gericaux to Insalaco and from Insalaco to his student. The three paintings are unified by a simplified color scheme, dominated by red, blue yellow, black and various browns. The individual paintings are distinguished by smaller areas of the three complementary colors, one for each painting, from left to right, purple, green and orange.

What makes the third painting so straightforwardly significant is how it stands as an emblem of Insalaco’s place—and any lone, independent artist’s place—in the art world. It’s essentially the perfect symbol for a painter who has found no home in what’s happening now, and who chooses to use traditional methods to illuminate contemporary life.

It’s clear at first glance why Insalaco would have chosen Raft of the Medusa for the third and final painting in the series. It’s self-referentially about the perilous, dicey chances for survival of genuine human values in life and especially now in art. Castaways on a life raft are waving rags to catch the attention of their only means of survival, a tiny and distant ship on the horizon. The raft embodies their hope. In the case of Gericault, it represents the art of painting itself, as ark that preserves fundamental human values. It’s self-referential in this general sense, but a more personal one as well, as Tom tells it:

Gericault was riding into Paris on his horse, which reared and threw him off. He fractured his spine and died in his mid-30s. He once said, “If I had done only one important painting in my life I would die happy.” He’s already done Medusa. He didn’t even think it was important. But it’s hanging in the Louvre. He succeeded, but didn’t know it.

The painting created an international sensation, generating both massive praise and condemnation. As Gericault’s own metaphorical life raft, it did it’s job perfectly: it established his reputation for generations but also because it was in defiance of the economic order that surrounded him. He’d built it to free himself from commissioned work, the system itself. In the process he chose to depict people doing virtually the same thing in a more savage context.

Here is how Insalaco describes the historical event:

The French Revolution was in 1789. By the beginning of the 1800s, there was a restoration of the monarchy. The new king promoted all of his cronies to be upper echelon leaders in the armed forces and some jerk who had hardly ever been to sea was promoted to admiral and put in charge of the ship called the Medusa. Everybody knew the navigation routes to stay off the West Coast of Africa, to avoid a huge sandbar, but this arrogant jerk goes over the sandbar, and the ship gets grounded, and there are only enough lifeboats for him and his cronies. So the rest had to build a raft for themselves to survive on the water.

Raft of the Medusa is the perfect metaphor for Insalaco’s own work and the self-banishment of his career, which has given him the freedom Gericault wanted. Gericault’s symbol for the freedom he craved was a DIY raft, built by those left for dead when the first-class community on ship saved themselves in the lifeboats. Insalaco has built his own raft, and he continues to survive, both literally and artistically.

7

Tribute Triptych depicts an artist floating in the delta of art history, acknowledging predecessors and influences but more importantly finding his own means of expression. His work is an assertion of an individual artist’s ability now to adopt techniques and methods from earlier periods, not for the purpose of commenting in a political way on that work, but in a sincere adoption of those methods because they continue to illuminate the human condition in the same way that they did when they were painted. Postmodernism asserts that we’re all late-comers to art history, but this is liberation rather than a curse. Insalaco assumes correctly that history has finally freed artists to do anything they like without having to think about history at all. The end of art history isn’t the end of painting, but a freedom from the obligations of history—the need to fit in with the times. Artists no longer have to serve the idea of history as forward progress toward better or more “relevant” ways to make art. All art is contemporary now, no matter how it’s made.

No one is a latecomer to anything anymore. Arthur Danto pointed out what was hidden in plain sight, that the notion of forward progress in art history ended with Pop Art and Kuspit announced the “end of art” in recognition that the idea of an avant garde has died and taken with it an easy way to create a new buzz or open up new possibilities. Everything is already possible. All frontiers have been opened up already. Discovering what’s necessary now, individually, is the hard part. The old notion of “new” has changed in that it has receded as a way of determining what’s worthy of attention—newness is personal now, not historical, and therefore much harder to discern. Danto pointed out that advances in art became impossible after Warhol’s Brillo boxes demonstrated, once and for all, that anything could be considered art. Whether this is a good or bad thing, it’s at least a once-and-for-all declaration of independence for individuals. Danto doesn’t take this insight to the irksome conclusion that even art created exactly as it had been in the past can be just as relevant and powerful now. This last pill is the hardest to swallow, because it forces everyone involved in the enterprise of art to root down deeply enough to discover what matters most—the unpredictable reality that what’s good for each individual artist, without regard for the vagaries of history or the dictates of cultural guardians who’ve lost sight of the profound commonalities in all human values. When Danto says that all art has to come with its own built-in philosophy of art now, it’s a thinker’s way of saying what no genuine painter needs to put into words. A painter does what he can’t help doing, and the critic is free to run alongside, building a philosophy to justify it. Or not. A great painting will be just as good either way.

John Currin can paint as a belated Mannerist, though maybe with a slightly ironic smirk, but few are willing to admit the smirk isn’t required. Anyone is free to be another El Greco if he or she is equal to the task. Anyone who now could paint exactly as Vermeer did would be a very great painter indeed—and would deserve the crowds he or she would draw—for precisely the same reasons Vermeer has been beloved. This latter-day Vermeer’s subjects might be wearing Chuck Taylors and Warby Parker glasses, but otherwise, everything that holds true for a painting by the Dutch master could hold true for anyone now with the same genius. A contemporary “Vermeer” would work exactly for the same reasons the Old Master’s paintings worked. Old methods become new when they are used to enable the viewer to see through the contemporary world toward something enduring, and the old methods are automatically new when they are filtered through a unique, individual sensibility. Spend a little time studying Piero’s The Nativity every day for a few weeks, or Robert Campin’s Merode Alterpiece, and you’ll realize that if someone had painted them last year, exactly as they were painted centuries ago, the work might easily be greeted with critical praise for their idiosyncratic, technical brilliant. They worked as religious icons in their time, yet they could work just as powerfully now as ambiguous, heightened visions of the spiritual depth in everyday life—full of humor and surprise and utter deadpan weirdness. They’re uncanny and yet utterly alive, filled with both a stylized feel of daily experience and yet as numinous as a still frame from a Tarkovsky film. Painted a year ago, they could have emerged from the vision of a defiant contemporary artist bent on asserting that the values of the past, both spiritual and visual, remain as true now as they were then. And they would work, because those values still work.

The rediscovery and embrace of Piero by so many diverse 20th century artists testifies to the fact that there is no longer a right and wrong way to make art. Nevertheless, even if as a postmodernist you accept the cultural relativity of all values, the core values of the Western canon remain as pertinent as ever now. Even if those values were randomly assembled together for no other reason than to make an exploitive civilization possible, and to strengthen the power of the few, they’re still one of the most enduring and practical set of codes for improving human lives. The postmodernists ask for nothing more from any other cultural norms. But the values that undergird Western culture are more than human improvisations. What was beautiful three millennia ago is beautiful still—not because we choose to think it’s beautiful, but because in an absolute sense it just is. The core truth of human life hasn’t changed, and in reality truth isn’t simply a matter of cultural practices—truth isn’t up for grabs by whatever force claims power over it. Maybe it’s the last revolution in art to assert that nothing in art is, nor ever was, revolutionary—it was just a series of partial realizations that everything in art is permitted, on the path toward the realization that we’re free to do anything we damn well please. The footnote to that is: it’s a terrible freedom, as the existentialists recognized. Sorting the wheat from the chaff in art isn’t about art history—art history is over—but about individual idiosyncrasy, and the intricacies of personal vision, as Kuspit insists from many different angles in his writing.

Now the hard part begins. It remains true that only certain things are actually worthwhile. The ultimate challenge now is to figure out how to make something genuinely worthwhile in a world where everything is permitted. A place to start is for an artist to quit thinking of career, and money, and any other motive and simply do what he or she loves to do most, in near-total privacy, if that’s required—in the end, quality trumps every other intellectualized justification for a work of art. Love is the parent of what’s good.

Insalaco loves his life and his work. He doesn’t fret much about any of these considerations other than to put himself safely beyond the reach of the art world’s machinations. He’s happy on his raft. He knows what’s good when he sees it emerge from under his brush, and even if he couldn’t tell the good from the bad, he would still get up every day to paint. What he mentioned to me about Chuck Close applies equally well to the phantom of Canandaigua: “He said he had to keep painting or he’d die. So he kept painting.”

[1] (I created a Tumblr account and posted images of the paintings I refer to in this essay. Aside from what Oxford Gallery has on its website, I believe these are almost the only images of Insalaco’s paintings accessible by brower at this point .)

[2] Pp. 30-31, The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley, Harper & Row, 1990.

Hi I am Toms brother Gary ! I would love to see your images of my brothers paintings ! Your article is spot on ! Tom makes no effort ,except for his art ! Lol he has always been focused in that area, almost exclusively ! Thank you for your article ! It’s great to know Tom is still producing art ! I paint now in my retirement ! Love it,lots to learn !

Hi ,I am Toms brother and would love to see your photos of his work ! Great article,by the way,