More of Henry and me

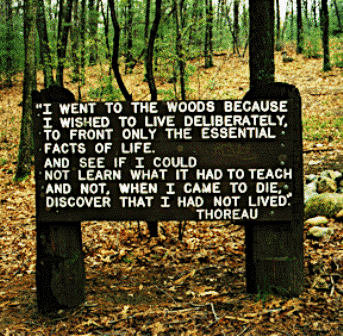

After a couple years in the working world, when I decided to return to college and enter graduate school to study literature in the 70s, I read Walden. It has always struck me as an essential book for anyone attempting to leave behind commonplace assumptions—the sort of wisdom that advises you to focus on earning money, gaining power, being well-known, contributing to society, and so on—and simply spend a couple years doing nothing but being aware of life. (Of course, if you get married and have children, all the commonplace wisdom kicks into gear, which is what happened to me.) Granted, Thoreau found a more direct way to “be aware of life” than by studying what people had written about life, yet Walden is full of quotes, so I imagine his two years spent doing what most people would consider nothing was occupied with a fair amount of reading. Hence, Walden is a reasonable book to read before driving to Illinois to study Melville, instead. (I was still thinking fondly of you, though, Henry.)

After a couple years in the working world, when I decided to return to college and enter graduate school to study literature in the 70s, I read Walden. It has always struck me as an essential book for anyone attempting to leave behind commonplace assumptions—the sort of wisdom that advises you to focus on earning money, gaining power, being well-known, contributing to society, and so on—and simply spend a couple years doing nothing but being aware of life. (Of course, if you get married and have children, all the commonplace wisdom kicks into gear, which is what happened to me.) Granted, Thoreau found a more direct way to “be aware of life” than by studying what people had written about life, yet Walden is full of quotes, so I imagine his two years spent doing what most people would consider nothing was occupied with a fair amount of reading. Hence, Walden is a reasonable book to read before driving to Illinois to study Melville, instead. (I was still thinking fondly of you, though, Henry.)

I’ve always been pleased by the fact that, early on, Thoreau shared his budget with his reader. It wasn’t really a budget, but closer to the equivalent of a receipt from Home Depot, detailing how much he spent on the little house (a room more than a house) he built for himself at the edge of the pond. I don’t know how much, in current terms, a dollar was worth in 1850, back before the Civil War began, but inflation aside, his investment sounds pretty reasonable:

Boards, ………………………… $8.03½, mostly shanty boards.

Refuse shingles for roof and sides, 4.00

Laths, ………………………….. 1.25

Two second-hand windows with glass, … 2.43

One thousand old bricks, …………… 4.00

Two casks of lime, ……………….. 2.40 That was high.

Hair, …………………………… 0.31 More than I needed.

Mantle-tree iron, ………………… 0.15

Nails, ………………………….. 3.90

Hinges and screws, ……………….. 0.14

Latch, ………………………….. 0.10

Chalk, ………………………….. 0.01

Transportation, ………………….. 1.40 I carried a good part on my back.

In all, …………………… $28.12½

These are all the materials, excepting the timber, stones, and sand, which I claimed by squatter’s right. I have also a small woodshed adjoining, made chiefly of the stuff which was left after building the house.

I intend to build me a house which will surpass any on the main street in Concord in grandeur and luxury, as soon as it pleases me as much and will cost me no more than my present one.

A house for $28. I think you might have gotten a foreclosed underwater house at auction in Detroit for that in 2009, but I don’t think I could build even a Lego version of Henry David’s home on that budget now. I’m not sure it would pay for a movie for two, if you require popcorn.I love the asides. He bought more hair than he needed (for a shirt maybe?), and he kept his transportation costs low by carrying much of his future house to the pond himself turtle style. The final assertion that, as soon as it pleases him, he will build the equivalent of a McMansion from bustling downtown Concord, and it won’t cost him a penny more than his current shanty—this is typical Thoreau, where you can’t tell if he’s actually figured out a source for free stolen rafters or that he’ll simply see his humble abode for what it is, as effective as a mansion for confronting the best life can offer, directly, which he proceeds to do and recount in his book. “The best life can offer” meaning simply learning how to see what’s always been there around him in the smallest aspects of the natural world, and the way in which his sustained attention to it was a form of alchemy, revealing something like spiritual gold in what he might have thought was just a stagnant little backwoods body of water. I suspect this better house he promised he would be able to build, as if he were turning water into wine, was the book he published. The citizens of Concord, and the world for that matter, were free to come and go inside that new house whenever they liked, and still are.

For me, this remains a model for how and why art gets made. As an act of paying sustained attention to what’s there and building some sort of home out of that attention: a picture, a poem, a script, a song. And with his budget, Thoreau was attempting to show that, even if you adjust the numbers to allow for inflation, his house was affordable to almost anyone who had saved a bit. In other words, to devote your life to the act of simply paying attention was something nearly anyone could afford to do. And that’s the question: is it affordable to devote yourself to making art? This past weekend, while staying with friends in New Jersey on my latest drive into New York City, a friend said, “What would you do if you didn’t have to worry about money?” My immediate response was, “Well that won’t be happening. And I’m already doing what I would do if I didn’t have to worry about money, but I’m not doing it as much or as well as I would if I were rich. I’s impossible to leave money out of it. Money counts.” I don’t make all that much, but so far I make enough to let me make art for at least a few hours every day. The trick is to get to that “enough” and then use what freedom remains to do what you’re best at doing. I’ve come a long way from graduate school, when I had what I considered a “free ride” in exchange for working as a teaching assistant. I work a lot harder for a living now and I spend more money than when I was a student. Even so, I make less than the median personal income for someone with a master’s degree—according to Wikipedia—but so far iwe’ll probably be able to pay off our home equity line of credit this year, and my wife and I both own our cars. In other words, no debt, including credit card debt.

I write this blog in the spirit of Thoreau: there’s no money in it and no need for it. I’m privileged to do other kinds of writing for core income, and sell an occasional painting to supplement it. Most of my sales come from Oxford Gallery here in Rochester, even though I have work for sale at websites where people anywhere in the world could see the paintings, including Amazon’s beta version of an art market, thanks to my dealer here, Jim Hall. (So far, no sales from that channel. I have sold work on-line occasionally thanks to another website run by a good friend.) Three years ago, I joined Viridian Artists in New York City, an artist-owned gallery that survives on membership fees, along with fees it collects for juried shows, and occasional art sales. Occasional. Let me repeat that. Very occasional. I allowed my full membership to lapse at the end of last year and won’t decide whether to resume those payments until after I’ve had my solo show in June. I’d like to renew it after that—I’ve stepped down to an affiliate status for much less expense right at the moment—but I’m still wondering if there isn’t a less costly way to show my work in New York City. Of course, there is, but it would mean being invited to show at a gallery that has to sustain itself with sales rather than fees.

There’s always the option of not showing work in New York City, but that’s a complicated decision. Manhattan may not be the center of the global art world anymore, but it’s one of the biggest portals into it. I know two extremely talented artists whose work is, to me, dramatically different, but whose career goals seem exactly the same: to get into a New York gallery that shows work in the big art fairs. I suspect this has become what many artists see as the only path toward the dream of doing nothing but making art, by selling enough of it at art fairs to make all other money-making activities pointless. The practice of selling work through a gallery, alone, seems to be in steep decline. One of these two artists who show their work here in Rochester has achieved this goal and now shows in a Manhattan gallery that can afford to sell work at the fairs. (I haven’t had the chance to ask him how that’s coming along.) The other, younger artist hasn’t yet gotten into one of these galleries, but I suspect he will. Meanwhile he has a solid teaching/administrative career in a good art school and a remarkable resume.

Three years ago, rather than approach, say, a dozen galleries in New York City, to see if they would be interested in showing my work, I accepted Viridian’s invitation to join and have been extremely happy that I did. The only catch is that it’s become less and less affordable, on my income–though some members at Viridian can afford it much more easily. When I was deliberating about whether or not to join, I spoke with Matt Klos about it, interested in whether or not he’d ever considered joining a gallery like Viridian. (First Street, Prince, Bowery, Blue Mountain, and many others offer memberships to people whose work is approved by the existing membership. They all charge fees in the same ballpark.) He said, with some pride, that he’d never paid to show his work—though we all enter juried shows where a small fee is required for the consideration of work. I knew what he meant: he’d been awarded a free solo show at Prince Street Gallery, but had never had a membership at any of them. Yet he allowed that it wasn’t a senseless thing to do: “Stanley Lewis has always shown at Bowery. He’s never sold through a commercial gallery. It works for him.” This actually helped me decide in favor of my membership. Lewis isn’t a big-money superstar. His drawings and paintings are intensely idiosyncratic, physical objects that require you to see them in person. He’s hugely respected, as demonstrated last year with his inclusion in a fantastic exhibit, See It Loud, at the National Academy Gallery, along with work from Neil Welliver, Paul Resica, and Leland Bell. If Stanley Lewis stayed with Bowery for so many years, and I suspect he could easily move to his pick of bigger-name galleries, then it seemed like a reasonable choice to spend the money, show the work and see where it led. The catch is that Lewis sells his work for significant money—not the numbers I associate with the superstars or the art fairs, but far more than most artists would ever dream of making from a painting or drawing. So the lower commission taken from sales at a gallery like Viridian or Bowery makes perfect sense for a Stanley Lewis, as long as the work continues to sell for what it’s worth. So if there’s a path toward a market, a membership at a gallery like Viridian makes sense and offers a family camaraderie that other galleries probably can’t provide. But you have to get past the initial sticker shock. And it might make sense to stay with a Viridian, or Bowery, for other reasons as well, as long as the money for fees comes along.

(Next: the cost of building my solo-show house, minus the need to pay for hair other than what’s in my brushes, and a consideration of whether it’s been worth it and may be worth it again.)

Comments are currently closed.