Costs, rewards, deliberations

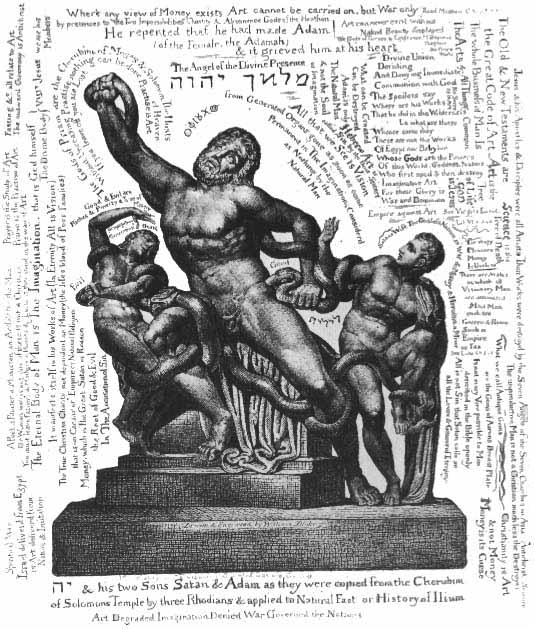

“Where any view of Money exists Art cannot be carried on . . .”

–William Blake’s annotations to the Laocoon

I grew up in a world in which what artists aspired to was to be able to go to their studio, make art, sell a work occasionally, so they can buy some Wheaties, and some records, and listen to records, and make art, and eat Wheaties. And that was their goal: stay away from the straight world, and stay away from the university, and live their lives.

When I was invited to apply for membership at Viridian Artists in 2011, I didn’t first take my samples around to regular commercial galleries in New York City to see if any would represent me for no charge other than, well, half the revenue of anything they sold. Fifty percent commissions didn’t bother me. That’s standard. A gallery has to eat too. At the time, I didn’t think I had the track record to have, say, a Hirschl & Adler take me on—wishful thinking even now, no doubt—yet I still deliberated a while before committing myself to $7,500 for two and a half years of participation and a solo show. (That $7,500 is only the beginning, as I’ll describe shortly.) Once I joined, my first task was to help the gallery move from its old space on W. 25th St. to its current spot on W. 28th because it was already in need of a less expensive venue for its members—as real estate continues to get pricier in New York City. By “help the gallery move” I mean I carried a lot of stuff down several floors and crammed it into the bed of Rush Whitacre’s pickup, at which point we drove it a few blocks north and unloaded it. Putting in the labor was part of the deal. Members agree to work at the gallery for many hours every year, which is a way of supporting it, but also, for those of us who live hundreds of miles away, another additional cost and benefit. The cost you measure in dollars: gas, lodging, parking, beer, Philly cheesesteaks, Thruway tolls, rides through the Lincoln Tunnel, subway fare, and admission to museums. (Some of that isn’t really a requirement of membership but an unavoidable consequence of coming down for a visit.) The benefits of hanging around Manhattan are less tangible, but just as real, and I will get to those down below.

Now, three years later, I face the choice of renewing my full membership (I’ve cut back to an affiliate status for a third of the full fee, in my current holding pattern) or trying to get a commercial gallery to represent me for nothing but a commission on sales. I am at least confident enough in my resume to see what some other galleries will say in response to it, but I’ve gotten a little more seasoned about a typical artist’s prospects at any gallery. OK Harris closed just a short time ago, a sad development, and stories have been coming out for a number of years about the struggles many galleries face now, in this economy. I’m not sure if that’s about the tidal shift toward big-ticket sales at art fairs, or simply the way big money rises like cream toward the safety of expensive art, as if it were a shrewd alternative to bonds and stock in Apple. It seems to me that when so large sums flood into art as it keeps doing lately, the majority of the little guys who make low-profile paintings struggle harder and harder to find sales, like Main Street shop owners when Wal-Mart moves into town. From where I sit, it seems Jeff Koons and others like him keep marching toward a sea of gold, leaving scorched earth for so many others. (Re: Koons. Lauren Purje sent me a little bulletin this past week about how Bob Cenadella, God bless him, was staging a semi-comical, solitary street protest in front of The Frick, while Koons lectured inside about sculpture. The police weren’t sure what to make of him. To keep his butt out of the clink, Bob amused them into submission by explaining to the cops that he was crusading for quality art as the malefactor Koons, presumably held forth about giant balloon poodles inside the building. The authorities smiled for the picture Lauren took of them, and everyone was happy. Bob got away with his rant. Koons escaped unharmed.)

Wouldn’t it be nice if artist-owned galleries offered an option where we could all just break even—recouping the cost of making and showing art with enough moderately-priced sales to support the whole process? Wasn’t there a time when this was possible? I think for most members at galleries like Viridian, it’s a non-profit write-off, the largest line item in a long list of expenses involved in simply getting the work out in front of as many eyes as you can while paying the bills in other ways. I have to admit the costs associated with making and showing art have given me some big itemized deductions over the past five years and lowered my taxes significantly, by eating up a large chunk of my gross income, which is cold comfort for not having money to spend on other things, but it helps. (Thanks, tax code, and that’s the only thanks you’ll ever get out of me.)

So, about that $7,500 fee. Anyone out there who contemplates joining Viridian or any other artist-supported space—First Street, Prince, Bowery, Blue Mountain, etc.—bear in mind that the actual cost of being a member and having a solo show is actually higher that the fee. This is obvious from the start but at the start of nearly anything one isn’t inclined to think sensibly about it. I touched on this earlier. First of all, if you live in the city, or anywhere gentrification is spreading, such as Brooklyn, unless you’re clinging to a rent-controlled apartment, the cost of making art must be insanely high. Purje told me Walton Ford has moved from Connecticut to New York City (old news except to me apparently), so Gotham is certainly affordable if you’re, well, Walton Ford and, I guess, accustomed to real estate prices in Connecticut. Yet most artists must be fleeing to points much further away, like Hudson, or Woodstock, or staying in even snowier regions such as Rochester—about 350 miles to the west—where life becomes far more affordable while being a member gets significantly more expensive. (It’s similar to the way artists have fled London’s East End for towns like Bristol, for the same reason, as urban real estate becomes affordable for only the richest few.)

As a member who decided to put in his hours helping out at the gallery—moving it from one location to another, taking down old shows and hanging new ones, writing about the work of fellow artists, and so on—I needed to make an average of six to eight trips to the city every year as a requirement of membership. Tipping my hat to Thoreau’s budget for his little house in Walden, here’s what each trip costs for one day’s visit:

Gas: $100

Lodging for one night: $150 (in Parsippany at a wonderful but the somehow affordable Sonesta Suites, with a half hour drive through the Lincoln Tunnel into the city.)

City Parking: $24

Tolls: the cost of simply going under or over the moat that surrounds the fortified castle, $20, to and from.

Meals: $25-$150

Admission fees: $20

Subway: $5-$10

So that’s roughly $375-$400 for a day’s visit, and I usually try to stick around for more than that, two days, or two nights and two-and-a half days. In that case, the cost of the visit goes up to $600-$700. With a minimum of six visits per year, that’s another $3,600-$4,000. The fee for membership came to $3,000 per year, so the travel costs effectively double the fee. So now we’re talking about $15,000 for a full membership lasting two and a half years. The solo show itself has additional costs, which are covered by the artist: any printed material used to promote the show, any advertising, all costs of the opening itself—cheap wine, canapes, bottled water, scruffy young man in the corner playing interpretations of Bitches Brew on acoustic guitar, what have you. The largest expense, aside from the printing, is simply the cost of transporting the paintings to the city. I’ll rent a minivan from Enterprise or Budget, swathe the paintings in bubble wrap and drive down to the city with them, and then drive it back a couple days later: $350 or so? For my solo show in June I found a way to print a thousand 16-page full-color, perfect-bound catalogs, offering images of all 18 paintings in the show, for around 50 cents each. Incredible as that sounds, this represents one of the minor economic windfalls of advancing digital technology and the Web, both of which are hollowing out our economy, but at least they’re helping the struggling artist who wants to send high-resolution images of his work out into the world. The postage to mail one catalog will add up to more than it costs me to have it printed. Amazing, and something all galleries ought to be doing. (I’ll do a post with details on what was involved and some help with the learning curve for designing a catalog. It took me twelve hours to teach myself how to use the Adobe software I leased to design the catalog.)

As painful as all this is to read, as I type it, my thirty months of membership at Viridian will have run me somewhere around $17,500. (I’m not even adding in the cost of renting a minivan three years ago and bringing half a dozen paintings down for review to get my membership approved, which involved having my rental van towed by the city police because I’d been unloading in a restricted spot. It took me two hours to get my car out of the pound, a huge cavern filled with abandoned dust-covered vehicles, which extorted more than $200 dollars in fines before it gave me back my vehicle.)

Now, none of this would be an issue if I were to sell only three large works in the show. I’d essentially break even. But this is not what typically happens at an artist-supported gallery. As I just pointed out, it does happen for emerging artists who have found a track through the network of gatekeepers—professors, critics, gallery owners, grant-bestowers, critics, and so on. In a recent interview, Dave Hickey said that he knows young artists, not long out of school, who have waiting lists of forty people ready to buy work as it’s produced. And I visited one gallery on my visit to the city a week ago where computer prints of digitally-created scenes based on old Nintendo and Atari games, mixed with Renaissance iconography, were selling for prices between $6,000 and $15,000. I was amused by the work once I figured out what was going on, but it was a lot to pay for color printouts pasted onto sheetrock to resemble worn fresco. So the likes of Mr. Koons may not be sucking all the oxygen out of the world for younger artists, though I haven’t been keeping track of whether or not the work I most deeply admire is actually selling.

The more I’ve deliberated on the money I’ve invested in my membership at Viridian, the closer I’ve begun to pay attention to the broader benefits of belonging. If you want to get the most out of being a member at an artist-funded gallery, you get to know as many of the other artists as you can and spend as much time in the city seeing whatever art is on view, as well as visiting other studios. For the past three years I’ve done a lot of the first, as much as possible of the second, and some of the third. All three dividends of my membership have been extremely valuable, both in their effect on my art and my outlook, and simply in the encouragement and support of the friendships I’ve formed. A couple days ago, I tried to list in my head all the shows I’ve seen while on a visit to help at the gallery, and it’s a long list: Piero Dell Francesca, Vermeer and Rembrandt at The Frick; Neil Welliver, Albert Kresch and Paul Resica at the National Academy Museum; Michael Borremans and Raymond Pettibone at Zwirner; Susie MacMurray at Danese; Walton Ford at Kasmin, and Henry Coupe at Viridian, as well as a couple dozen other opportunities to stand a few feet away from something wonderful. Part of the joy of making art is getting to know other artists, learning from them, being influenced by them, as well as being someone a few of them like to spend time with. My three years with Viridian have given me countless occasions to spend hours with friends I’ve made through the gallery: Lauren Purje, Vernita Nemec, Rush Whitacre, Gary Lee Cordray, Jennifer Wenker, Bob Cenedella, Bob Mielenhausen, Alan Gaynor, Arthur Dworin, Kat King, Ann Coupe, Jane Talcott, John Lloyd, and many others. Without having become a member I never would have spent an evening playing shuffleboard at Nancy’s Whiskey Pub with Bob Cenedella, Lauren Purje and Rush Whitacre. Need I say more?

Conclusion: some unaffordable things are worth it. Should I do it again, now that I know how much I would actually have to spend for another few years? It isn’t so much “should I” as “can I?”

Comments are currently closed.