One safe place

How many roads you’ve traveled/How many dreams you’ve chased/Across sand and sky and gravel/Looking for one safe place. —Marc Cohn

I spent a couple hours with Matthew Cornell shortly after his opening at Arcadia, talking with him about his work, and it was nearly as rewarding as the hour it allowed me to spend just looking at his exceptionally personal and accomplished paintings. I got there early and had already spent a quarter hour moving from painting to painting, amazed at the way he can evoke unsentimental feeling from images of ordinary, nondescript middle class streets. His work is photo-realistic, but he softens it almost imperceptibly to a dreamlike quality that, for me, hovers between day and night, waking and sleep, memory and immediate sensation. In one painting after another, you feel slightly like a child racing through the dusk from far away, late for dinner, finally catching sight of home. You look at his images and think, “This is America, and this is where I want to be, if I could only get back inside this house.” I’d seen examples of his smaller paintings before at Arcadia, and most of them are modestly scaled, but Pilgrimage, a series of scenes depicting the houses where he and his family lived over the past half century, gathers individual paintings into a larger context that offers a respectful, loving celebration of middle America, haunted by loss but full of quiet, patient vitality. It’s as if he’s nostalgic for a quality of life that has only gone into hiding, biding its time, waiting to re-emerge. Most of the work was already sold, two days after the opening, and that fact—paired with the impeccable quality of the paintings—buoyed me with a sense of hope that simple, direct, and genuine painting, full of love for its subject, without relying on cleverness or pretension, can find a market even in New York City, at prices that reflect the actual value of the work.

Matthew met me at the gallery, only hours before he was to fly back to Florida. He turned out to be tall, good-looking, with a youthful manner for someone who recently turned 50. He was layered up against historic cold temperatures here in the Northeast that must have felt especially bitter after flying to Manhattan with his wife, Rachel, from Orlando, where they live. He told me he undertook this project, in earnest, after both of his parents died a little more than a year ago. We wasted no time and started getting to know one another immediately by talking shop. We began at home plate, as it were: with an oil of the house where he lives with Rachel now, a modest Cape Cod, with a studio in a separate structure at the back of the driveway, and a chain-link fence around the front yard. As with almost all the other paintings, Cornell  captured this home at dusk, late dusk, and the twilight both deepened the color and enabled him to stint effectively on much of the detail that might have been unavoidable in full daylight. Yet the chain link fence looked perfect, as if he had woven it from spider web. The lack of light intensified the beauty of the scene—at noon, it would have faded into a dreary, hard-edged matter-of-factness so typical of photo-realism.

captured this home at dusk, late dusk, and the twilight both deepened the color and enabled him to stint effectively on much of the detail that might have been unavoidable in full daylight. Yet the chain link fence looked perfect, as if he had woven it from spider web. The lack of light intensified the beauty of the scene—at noon, it would have faded into a dreary, hard-edged matter-of-factness so typical of photo-realism.

“That’s our house. We live there. My studio is lit up slightly in the back,” he said.

“The fence is incredible.”

“A lot of it comes from experience but that fence has to be painted at the right time of day. I put clove oil in the paint so it extends the drying and so as not to have too hard of an edge. When the paint is in-between dry and very wet, you have to make these tiny, subtle kinds of lines. A fence, sometimes at night you can see it very clearly and sometimes it’s kind of invisible. It has to be very subtle . . . some of it you can almost see, but not quite.”

“It’s exactly right,” I said. ”The mesh is a perfect grid, but you step back, and it’s like a film.”

“It’s not about getting every detail.”

“You must use tiny brushes.”

“Triple zero,” he said, laughing. “It isn’t as if there are just two hairs in there.”

“So this is in Orlando, right?”

“Yes. Long story. Rachel and I had met in Ann Arbor. The next year we kind of had a date, basically. I went back home, living in Kentucky, and I decided to meet her about four months later, and we hit it off pretty well, so I decided to move to Florida. Rachel decided to come with me. We lived in a tiny apartment, no furniture, for about a year. That was thirteen years ago. It’s the longest I’ve lived in one place. I moved from that place there (he pointed to another painting of his previous home), to this one here. This was built in 1929.”

We took a few steps toward the front of the gallery, on Greene St., and stopped at a painting (one of only two in the show I didn’t think were as successful, depicting homes lit up in the middle of the day). As it turned out, this was a home where he had lived as a child, and it had been torn down, so he had to work from a tiny scrapbook photograph. It showed. As an exception to the rule, this painting demonstrated how much he depends on a methodical process for capturing and creating each of his images: spending time at the site, taking notes, doing sketches to remind him of the colors that go missing in a photograph, as well as taking multiple photographs in order to assemble all the information he needs for the painting itself. Once he starts, he continues to make changes to what he saw and what his photographs record, removing objects, modifying color, eliminating detail as well as fabricating elements in the image, as needed. The process is far from a simple replica of a photograph. (It’s a mode of working that was evident in the work of Richard Estes, as well, when I visited his retrospective uptown a day later. Both shows proved how far photorealism is from an act of simply copying a single photograph or even several photographs.) Cornell also paints quite a bit on site, even at night, which helps with the results when he continues to work in the studio.

We moved on to one of the most ambitious pieces in the show, called Lascaux, a triptych, with a portrait of  one of his childhood homes flanked by replicas of his own childhood drawings. He re-discovered them during a visit inside this home during his project, when the current owner—who bought the house in 1979—took him and Rachel down into the basement to show them that Matthew’s scrawls were still there, untouched, after decades. The three paintings together are a fantastic evocation of lost time, because for a few seconds you think his former home is flanked by reproductions of actual prehistoric paintings from the Lascaux caves. Then you realize the dinosaur could have been done in crayon—and there were no dinosaurs on the walls of Lascaux. The triptych makes palpable not only the decades of Cornell’s own life, but hints at spans of time that dwarf any individual’s few years on the planet.

one of his childhood homes flanked by replicas of his own childhood drawings. He re-discovered them during a visit inside this home during his project, when the current owner—who bought the house in 1979—took him and Rachel down into the basement to show them that Matthew’s scrawls were still there, untouched, after decades. The three paintings together are a fantastic evocation of lost time, because for a few seconds you think his former home is flanked by reproductions of actual prehistoric paintings from the Lascaux caves. Then you realize the dinosaur could have been done in crayon—and there were no dinosaurs on the walls of Lascaux. The triptych makes palpable not only the decades of Cornell’s own life, but hints at spans of time that dwarf any individual’s few years on the planet.

“We went down in the basement, like a cave, and discovered these things on the wall,” Matthew said. “He had had this house since 1979 and they never touched the drawings.”

He laughed, and I suggested it was a lucky accident that the current owner felt the urge to preserve even Matthew’s own childhood murals.

“They do look like cave paintings,” I said. “You’ve used the gesso’s texture to duplicate what the mortar would look like between the blocks. It’s as if you’d cut these things out of the wall.”

“At one point, I really did think I should just carve them out of the foundation of the house . . .”

I kept marveling at the sureness and steadiness of the tiny lines in his scenes.

“I take dental floss and tape it across the canvas and get it as straight as I can. I just follow it. I have to lean against stuff. I could use a maul stick but I try not to touch the surface. I like to have other things in my hand so it’s hard . . . I feel like a sherpa holding onto things as I paint.” Using aids like this is a recent development; previously he’d worked mostly free-hand, which was more time-consuming.

In the painting we were examining, as he does in many of them, he contrasted the alluring amber interior light, glowing in the window, with the cool tones of the falling night outside. Yet within his windowpanes you glimpse more than the warmth of some obscure private world—you can actually see into it. The sense of depth is so convincing, you feel as if you are looking through a window in the canvas or panel itself. You feel as if, by moving your eyes, you would unveil the edges of new things just out of view, painted on a recessed surface mounted slightly behind the canvas or panel.

“The depth you get in these interior rooms. It’s perfect. It’s as if you are looking through frosted glass.”

“I try not to make everything perfectly sharp,” he said. “It would take away a little of the mystery.”

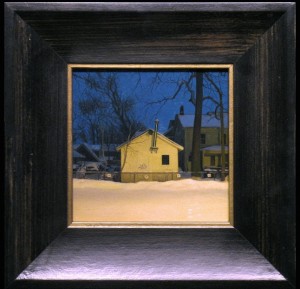

We moved on to one of the most minimal paintings in the show. It depicted a shed behind the home of a friend, lit up by a floodlight from the back of the house—with a fence on which were hung numbers for parking spaces, each one slightly askew. Behind the illuminated shed, with nothing but snow before it, was a murky backdrop of homes along the next street, the properties rendered in blues and greens and violet. It was the view through a door or window into the back yard of a friend’s place in Ann Arbor. He’d managed to capture just the right level of detail in both the brightest and darkest regions of the image, which is nearly impossible to get right with a single photograph, even using HDR. He had to do much of it from memory or imagination.

We moved on to one of the most minimal paintings in the show. It depicted a shed behind the home of a friend, lit up by a floodlight from the back of the house—with a fence on which were hung numbers for parking spaces, each one slightly askew. Behind the illuminated shed, with nothing but snow before it, was a murky backdrop of homes along the next street, the properties rendered in blues and greens and violet. It was the view through a door or window into the back yard of a friend’s place in Ann Arbor. He’d managed to capture just the right level of detail in both the brightest and darkest regions of the image, which is nearly impossible to get right with a single photograph, even using HDR. He had to do much of it from memory or imagination.

“If I were doing photography for a painting like this I would do two or three shots and use one f-stop for this and another for that,” I said. “That way the darks and lights don’t just wash out.”

“I’m not a great photographer. You have to adjust based on what you know, not what you see in the photograph,” he said. “I eliminated a fence in one painting. Here I changed the house because there was a door and it didn’t work. I had to repaint it.”

I observed that he often worked to get three sources of light, at least, into an image: the setting sun, the ambient light reflecting off the sky, an interior light from a house, or houses, and even a streetlight just coming on. We stood before another painting that looked to me as if the façade of the house were lit directly by the last few rays of peach-colored light from the sun. Yet he said the light source was a neighboring ball field. And the light from the sky wasn’t from a sunset at all, but was deflected off clouds from the glow of a nearby city.

For all his photo-realistic methods, the slightly intensified color in his scenes has roots in the work of a fantasist I recall mostly from posters in college dorms from the 70s: Maxfield Parrish. When he told me this, I thought, that’s exactly it. You can detect the heightened color of Parrish in many of his comparatively mundane scenes. Even his darkest shadows seem to have a musical resonance, never just falling off into brown or gray. His compositions are often as much about conveying a certain purity of color as they are a way of letting you see the world just as it is.

He’s constantly leaving things out of his images. Though they look at first glance like a duplication of everything on view, a warts-and-all portrait of the suburban and small-town world, he’s constantly eliminating as much detail as he can. In one painting he rendered a dozen cracks in the road by the house where his father grew up, and then he painted over them, smoothing the lane down to only a few. Sometimes, that process of elimination is unconscious.

“This is my mother’s house in Miles City, Montana. There’s something about the house that’s not right. Can you tell?” he asked.

you tell?” he asked.

I shrugged. “The window’s odd.”

“I did it accidentally. Look at the door.”

“There’s no knob.”

“I don’t know what that means. It’s intriguing,” he said.

The title of his show, Pilgrimage, refers not only to the months he spent on the road with Rachel, hunting down the houses where he’d lived, but also refers to the original hejira itself, his life, following his father from town to town, as an Air Force brat. He has lived in Kentucky, Florida, several places in California, Illinois, Kansas, Ohio, Michigan, Idaho, New York, and other places as well. His wife is from Michigan. His father was from Kentucky, his mother from Montana. He will talk your ear off about his beloved dad, who went to work as a contractor, building and repairing a retirement community, when he retired from the Air Force. He said, “That’s my father. Working late. Never had an office job. He was a working man, sun up to sun down. Nobody worked harder than my dad. If you see a painting of mine and there’s a building off to the side with a light on, that’s my dad.”

One of the best paintings in the show sums up his father’s character. It’s the show’s eponym, titled Pilgrimage, and it lets you see the low façade of his parents’ surburban ranch home with a pale blue-gray pickup truck parked in front. It’s a modest home, like all the others in the show, with a groomed yard, and that truck at the curb. The only flaw: his truck has a large, round dent in the rear fender—it looks as if someone has pushed a fingertip into something soft but firm—just at the edge of the tail-light. This was less a flaw in the vehicle than an essential, distinguishing mark of the driver’s character.

One of the best paintings in the show sums up his father’s character. It’s the show’s eponym, titled Pilgrimage, and it lets you see the low façade of his parents’ surburban ranch home with a pale blue-gray pickup truck parked in front. It’s a modest home, like all the others in the show, with a groomed yard, and that truck at the curb. The only flaw: his truck has a large, round dent in the rear fender—it looks as if someone has pushed a fingertip into something soft but firm—just at the edge of the tail-light. This was less a flaw in the vehicle than an essential, distinguishing mark of the driver’s character.

“That’s my Dad’s truck. When we moved to California they bought this house for $55,000 dollars. This was his last truck. He was so much identified by the trucks that he owned. My dad’s a good story. He hauled a lot of stuff. For some reason, they were hauling a big hot tub and it rolled off the back of the truck and wheeled around and smacked the back of it. He was always hurting himself, breaking something. Accident prone. He would always eat cereal in the morning and then he would put the empty bowl and spoon under the seat of his truck and head to work. So all day long, if you rode around with him, you would hear the rattle of the spoon in the bowl. You’re thinking, what is loose in here?”

I laughed.

“It wouldn’t bother him.”

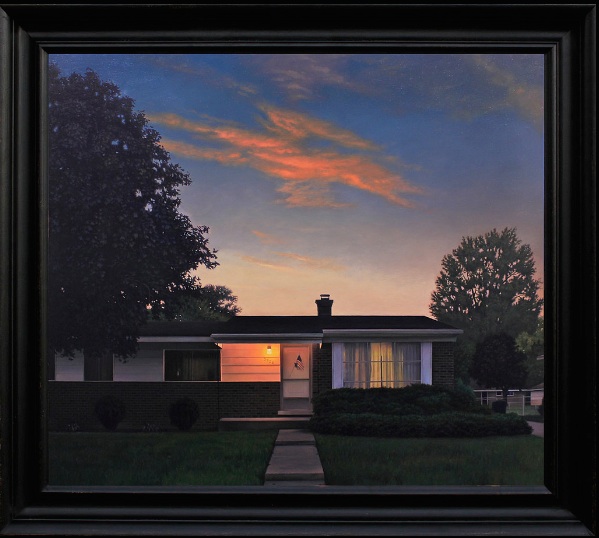

We ended up at the back wall of gallery, in front of the largest painting in the show, the home his wife’s father has inhabited for half a century. Rachel’s father lives there still, at the age of 87. It’s a small ranch just outside Detroit, in Waterford, with overgrown cedars sculpted into rolling humps of foliage. On the front door, inside the screen door, is a small tattered American flag where the door-knocker would be.

“This is the house Rachel grew up in. Her father, Chuck, still gets around. He’s Jewish, and he’s involved in his temple. He basically works full time even though he’s 87. His neighbor, a Presbyterian, has lived next door since 1959. They’re very different people, yet they have a friendship that’s lasted all these years. It’s a quintessential American house. For me, having been around the country, this is very much an American life, his life and this house and this flag on the front door. He’s had that flag there for like 15 years, and it’s a bit ragged. I said, “Chuck, why don’t you get a new flag?” he says he comes in from the side door. ‘I never go out the front door and I forget about it’.”

We spent a bit of time in front of this one, stepping away and then moving back close. Before we head out, Matthew said, of this painting, but also by implication, of the show as a whole, “It’s a testament to American life.”

I followed him out onto Green St. and around the corner to Le Pain Quotidien, where his wife had been waiting, so they could have lunch before they headed to the airport. She has a master’s in art, and was an artist when they met, but she has been working as a writer. She started a consultancy that enables her to help Ph.D. students who have become stalled with writer’s block in their dissertations. It sounded like an odd, rare niche, but when I sat down across from them at the table, she explained that it’s quite common. In other words, she’s finding a real market for the service.

“They’re all perfectionists, and they get stuck,” she said. She’s pretty, dark-haired, much shorter than Matthew, and they’re one of those couples who seem intensely aware of each another no matter what they’re doing, anticipating the other’s thoughts, identifying with each other’s lives. “My clients have been rolling the rock up the hill and they just can’t get it to the top.”

“You should call it, Saving Sisyphus,” I said.

She smiled, “Exactly.”

“Rachel, I want to point out, Dave drove five hours from Rochester to talk with me,” Matthew said, smiling. “So what I’m doing must matter after all.”

Nudge, nudge. She grinned, leaving that question up in the air, where it deserved to be— n terms of the ironic flattery it offered to both of us—as Matthew pulled out his smart phone and checked it. The screen was shattered but still functional. He was careful not to slice his fingers on the broken glass. He may be selling most of his work, but they’re still on a budget.

“This seems like a culmination, this show,” I said. “Everything has sort of come together for you.”

Rachel nodded vehemently, as if that was precisely how it felt.

“So if I were to put myself into your position, I’d be thinking what next? Where do I go from here?” I asked.

Matthew said he thinks he will probably move inside and maybe do a series of interiors that explore his present life. He’s journeyed back into the past, now maybe he will sink more deeply into the present.

“I want it to still be who I am,” he said.

“I think painting is always who the artist is if it’s an act of love,” I said. “If you love what you are painting you will be in that image. There is so much art that is just clever, or it’s commentary, or contrived, and the art becomes subservient to what the artist is ‘trying to say’, quote-unquote. There’s no heartfelt connection to what they are doing in the act of painting. I can tell you just love the process of putting that paint down. If that’s there, the person, the artist will be in it.”

Rachel nodded again and smiled.

“I don’t love all of it,” Matthew said, laughing. “But when you finally get it to work, you love it.”

“In so much of the show, you see that light inside the house and you feel as if you’re a kid again and you’re close to home.”

“When you see the light, you know you’re home,” Matthew said.

“Even when you’re just stating a fact about what you’re depicting, it sounds poetic. It’s a powerful show.”

Rachel nodded again and said, “It’s powerful because it’s the truth.”

Comments are currently closed.