Life vs. painting

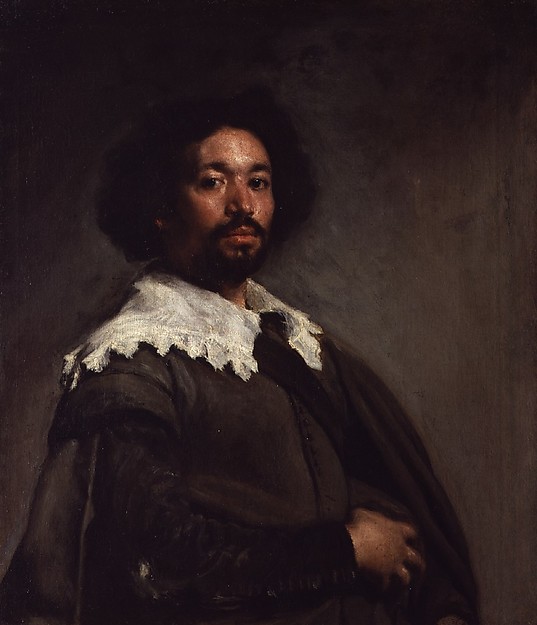

I spent Monday last week mostly wandering around the Metropolitan, re-visiting paintings I’d seen before and seeing a few things I hadn’t, including the murals of Thomas Hart Benton and an exhibit about Native American art, yet the work that made the deepest impression on me was this portrait. I’d seen it on visits before but I really spent some time with it. The quality of his paint is incomparable, and every time I see one of his paintings I understand why he had such a powerful influence over painters as diverse as Manet, Bacon and Fairfield Porter. Yet in this one, it isn’t just beautifully painted; the quality of life is uncanny. From the Metropolitan website:

An Appreciation of the Portrait THEODORE ROUSSEAU Vice-Director, Curator in Chief

The Metropolitan Museum paid an enormous sum to acquire the portrait of Juan de Pareja by Velazquez. The decision to buy the picture was made because it is one of the finest works of art to come on the market in our time. It is among the most beautiful, most living portraits ever painted. Velazquez, whose works are extremely rare, ranks with the greatest painters. This is precisely the kind of object which the Museum has a historic duty to acquire. An unusual thing about this picture is that we know what people thought about it when it was painted. The information comes to us from a Flemish artist, Andreas Schmidt, who was in Rome in 1650 when Velazquez painted it. Schmidt later went to Madrid, where he told the story to Antonio Palomino y Velasco, the historian of Spanish art, who published it some sixty five years later. Palomino tells us that when Velazquez was in Rome, where he had been sent to buy pictures for his master, the king of Spain, he painted the portrait of the pope, Innocent X. In order to practice before beginning his sittings with this supremely important personage, he did a portrait from life of his assistant, the young mulatto painter Juan de Pareja. This was so startling a likeness that when he sent Pareja to show it to some of his friends, it had a sensational effect upon them. They were literally astounded by it, and reacted with a mixture of “admiration and amazement” (the Spanish word asombro implies fright, mixed with surprise and admiration) “not knowing as they looked at the portrait and its model whom to address or where the answer would come from.” The portrait was then shown in an exhibition of outstanding pictures both old and new in the Pantheon, “where it was generally applauded by all the painters from different countries who said about this portrait everything else looked like painting, this alone like reality”.

Comments are currently closed.