The Condition of Music

The current show at Oxford Gallery, “The Condition of Music,” grows on you. Walk a few circuits around the gallery and spend time with individual work; it will open up and begin to resonate. Some pieces, though, make their impression immediately: Chris Baker adds a poetic twist to  one of his beautifully geometric construction sites by placing a musical quartet of hard-hatted players atop one of his buildings in “Building Suite.” At first you don’t realize they’re there, but then you spot them, letting their concert rain down gently on the work below. It’s a surprisingly poetic touch and reminded me, in a good way, of some of the best New Yorker covers, a meditation on the emotional polarities of city life. Tom Insalaco’s night cityscape opens a colorful new chapter in his work. The heavy traffic on a rainy, twisting highway creates a shining, brilliant-hued study in light and dark, with car lights strung along their lanes like musical notations on a staff. A post-rain rush hour, in what’s probably an early winter dark, never looked so good. Ray Hassard’s “Song” demonstrates, once again, his seemingly easy mastery of pastel, with one lone singer bathed in soft light where you can almost hear the melody in his color. One of the most

one of his beautifully geometric construction sites by placing a musical quartet of hard-hatted players atop one of his buildings in “Building Suite.” At first you don’t realize they’re there, but then you spot them, letting their concert rain down gently on the work below. It’s a surprisingly poetic touch and reminded me, in a good way, of some of the best New Yorker covers, a meditation on the emotional polarities of city life. Tom Insalaco’s night cityscape opens a colorful new chapter in his work. The heavy traffic on a rainy, twisting highway creates a shining, brilliant-hued study in light and dark, with car lights strung along their lanes like musical notations on a staff. A post-rain rush hour, in what’s probably an early winter dark, never looked so good. Ray Hassard’s “Song” demonstrates, once again, his seemingly easy mastery of pastel, with one lone singer bathed in soft light where you can almost hear the melody in his color. One of the most accomplished paintings in the show, Bill Santelli’s abstract, “Lining Up the Centers #2,” seems to conjure worlds within worlds, with his planetary spheres that swirl their atmospheres distinctly lit by a nearby star. They’re as colorful as oil on rain water. His geometric compositions bring to mind the later Kandinsky, yet within the confines of his precise and perfect geometry, a chaos of color seems to veil unpredictable mysteries. In “Blue Rondo”, Daniel Mosner offers a humble glimpse of a lone saxophonist, standing barefoot on a carpet, lit from behind by a soothing blue light, reflecting off the ceiling,

accomplished paintings in the show, Bill Santelli’s abstract, “Lining Up the Centers #2,” seems to conjure worlds within worlds, with his planetary spheres that swirl their atmospheres distinctly lit by a nearby star. They’re as colorful as oil on rain water. His geometric compositions bring to mind the later Kandinsky, yet within the confines of his precise and perfect geometry, a chaos of color seems to veil unpredictable mysteries. In “Blue Rondo”, Daniel Mosner offers a humble glimpse of a lone saxophonist, standing barefoot on a carpet, lit from behind by a soothing blue light, reflecting off the ceiling,  glowing on the walls. The foreground is shadowed, as is the musician’s body, so that he seems to be facing into the dark in order to light up the room with his rondo. Mosner captures the light perfectly, with small touches—the way it falls on the man’s toes, even certain spots of color in the Persian carpet and gleaming highlights that give shape to his sax. It’s a lonely, soulful moment— a study in brown and blue, an image of an artist’s obligatory solitude, beautifully vital and free.

glowing on the walls. The foreground is shadowed, as is the musician’s body, so that he seems to be facing into the dark in order to light up the room with his rondo. Mosner captures the light perfectly, with small touches—the way it falls on the man’s toes, even certain spots of color in the Persian carpet and gleaming highlights that give shape to his sax. It’s a lonely, soulful moment— a study in brown and blue, an image of an artist’s obligatory solitude, beautifully vital and free.

Kate Timm’s large still life, “Banjo Bottle with Violin Vase”, with its all-over flood of color, is one of her best, a complex assembly of objects, offering a view of a lush yard in the background, with a narrow strip of sky. She simplifies the complexity of her composition with bands of green, blue and muted orange. As with all her work, part of her achievement is to create a tension between a surface busy with its mosaic of exuberant color that resolves into an image of objects at rest in a world where outside and inside, foreground and background, seem to be a single continuum in which every little detail matters as much as all the others around it.

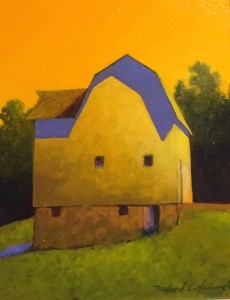

Rick Harrington, as well, offers a small barn that struck me as one of the best he’s ever done, a study in a similar set of colors—green, a Cadmium-yellowish orange, and violet. It’s both perfectly balanced, yet the barn is set on a bias and almost suggests a laborer trudging uphill, toward the right, with a load on his back. The color and the values of light and dark work in tandem, drawing the eye upward from the cool shaded grass toward the brilliant warm sky whose color seems to have crept down into the barn itself. Everything locks together like a puzzle solved with perfectly harmonized colors and shapes. Bill Stephens contributed a small calligraphic image of a tree, with a whimsical title that works as a pun in at least one or two ways (if you ask me), “Morning Timbre.” It’s likely one of the treetops viewed in the grove behind his studio. It seems to toss and sway in changing weather, with a pale yellow light showing through under the clouds. It reminded me of Burchfield’s ecstatic visions of his Ohio woods and fields. In counterpoint, Jean Stephens offers a tiny,

Rick Harrington, as well, offers a small barn that struck me as one of the best he’s ever done, a study in a similar set of colors—green, a Cadmium-yellowish orange, and violet. It’s both perfectly balanced, yet the barn is set on a bias and almost suggests a laborer trudging uphill, toward the right, with a load on his back. The color and the values of light and dark work in tandem, drawing the eye upward from the cool shaded grass toward the brilliant warm sky whose color seems to have crept down into the barn itself. Everything locks together like a puzzle solved with perfectly harmonized colors and shapes. Bill Stephens contributed a small calligraphic image of a tree, with a whimsical title that works as a pun in at least one or two ways (if you ask me), “Morning Timbre.” It’s likely one of the treetops viewed in the grove behind his studio. It seems to toss and sway in changing weather, with a pale yellow light showing through under the clouds. It reminded me of Burchfield’s ecstatic visions of his Ohio woods and fields. In counterpoint, Jean Stephens offers a tiny,

exquisite glimpse of two metal flutes sitting on sheet music, a work so small you can easily miss it, but don’t. Some of her paintings have a unique sense of intimacy, as if she’s giving you a look at something she doesn’t bring out into view for just anyone. In this work, the flutes reflect the sheet music beneath them. It’s one of the best responses to the theme of the show, capturing the immersive quality of music, it’s ability to erase boundaries between itself and the world a listener inhabits. When I listen to the music I love, the world I’m in becomes that music. Everything I experience is immersed in it rather than the other way around, just as those flutes show me everything around them, even though what they reflect is nothing more than the sounds they’re about to make. The title “As a Wind in a Forest” nods, with a wry smile, toward Bill’s storm-tossed tree, and the two paintings create a playful tension between motion and stillness, silence and sound.

exquisite glimpse of two metal flutes sitting on sheet music, a work so small you can easily miss it, but don’t. Some of her paintings have a unique sense of intimacy, as if she’s giving you a look at something she doesn’t bring out into view for just anyone. In this work, the flutes reflect the sheet music beneath them. It’s one of the best responses to the theme of the show, capturing the immersive quality of music, it’s ability to erase boundaries between itself and the world a listener inhabits. When I listen to the music I love, the world I’m in becomes that music. Everything I experience is immersed in it rather than the other way around, just as those flutes show me everything around them, even though what they reflect is nothing more than the sounds they’re about to make. The title “As a Wind in a Forest” nods, with a wry smile, toward Bill’s storm-tossed tree, and the two paintings create a playful tension between motion and stillness, silence and sound.

Anthony Dungan’s “The Metronome” is an abstract expressionist canvas that takes the triangular form of a metronome and the swaying motion of its pendulum as its subject and becomes a study of sound itself, the way it pulses and moves, near and far. Its muted color allows Dungan to work with a sense of depth as convincing as a representational painting’s depth of field. Areas of the painting recede, while others move toward the viewer, pushing and pulling in a different dimension from the back-and-forth of the pendulum. It’s a painting that finds an AbEx balance between control and spontaneity, structure and serendipity.

Anthony Dungan’s “The Metronome” is an abstract expressionist canvas that takes the triangular form of a metronome and the swaying motion of its pendulum as its subject and becomes a study of sound itself, the way it pulses and moves, near and far. Its muted color allows Dungan to work with a sense of depth as convincing as a representational painting’s depth of field. Areas of the painting recede, while others move toward the viewer, pushing and pulling in a different dimension from the back-and-forth of the pendulum. It’s a painting that finds an AbEx balance between control and spontaneity, structure and serendipity.

Probably the most idiosyncratic painting in the show, Debra Stewart’s take on the “Cantoria” of Luca Della Robbia, now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. It might never have been painted if she hadn’t happened upon an antique gold-leaf triptych frame which provided her with the stage, as it were, for her concert, populated not only with singers, following the Rennaissance sculptor, but also circus animals peeking wryly in from outside the frame, a friendly elephant and giraffe. Look down toward the bottom of the central panel and, through the cloud cover you can see, from your altitude far above the earth, a glimpse of the Duomo itself. It’s a joyful painting.

Comments are currently closed.