The forbidden pleasures of, uh, paint

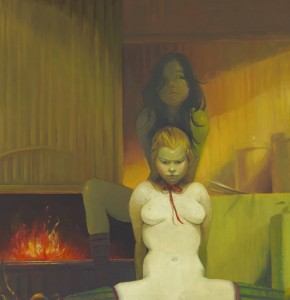

Detail from Fireplace by Lisa Yuskavage

A recent notice in The New Yorker with a title that made me laugh—Dangerous Beauty—compares a new painting by Lisa Yuskavage, Fireplace, on view now at David Swirner, to a couple paintings by Manet. It’s clearly a pastiche drawing from Olympia, and it shows what appears to be a seated sex worker naked except for her ribbon choker, backed by an attendant, or partner, with a fireplace behind her roaring with warmth. The tableau is a comfy little domesticated demimonde—exactly what Manet presented, with a smirk, in Olympia and Dejeuner sur l’herbe, a professional sort of nudity displaced into the bourgeois parlor and picnic. What was an outrage, at the time, now looks like wicked wit. In Fireplace, with the professional sangfroid of her spread legs, this temptress is more realistic than Yuskavage’s typical virtuoso performance, yet her pout is about as menacing as the work gets. Most of her paintings strike me as an adolescent fantasy which Alberto Vargas might have taught a Japanese anime artist to do on deadline for Playboy, with Russ Meyer attached for quality control. It’s caricature to mock the antiquated tropes of softcore pin-ups as a springboard to give herself license to achieve the innocently cheerful effects of light and color that actually interest her. The irony is that she needs to pretend that she’s offending you with her content in order to do, with color, something that actually just cheers you up, in a way that really does move beyond the settled boundaries of taste. The way she throws inhibition to the wind here is in her handling of color, not in the choice of subject, which is pretty tame. The danger is all in the palette. If you want something genuinely nasty, turn off SafeSearch and let Google take you by the hand and show you the way.

Critical comparisons to Vermeer are just jaw-droppingly knuckleheaded, but she isn’t too far from Fragonard’s coy eroticism. They both evoke sexual readiness as a career move, without investing much genuine emotion into anything but the execution of the work, which is impressive in her case (and was astonishing in Fragonard’s). But she seems to be satirizing—or should it be satyrizing—a harmless target. Her work feels like an amiable send-up of that old bugbear, the offending “male gaze”—but it’s the fevered stare of a 16-year-old boy circa 1967, a pimply kid who really buys into the perceptual distortions of chronic high school horniness. Everything seems unreal and weightless in Yuskavage’s world. Her girly-girls are over-ripe, vacuous fantasies. Yet they’re done in sickly-sweet colors that actually win you over, the more you see them—partly because Yuskavage has so completely surrendered to the excesses of her tongue-in-cheek kitsch. Her light and color, not her subject, have the feel of genuinely guilty pleasures. You sense that she’s giving in to the ease of her painting skills like a girl on a diet, with her bedroom door open–just try to stop me!–spooning her way through a gallon of French vanilla in a single sitting. Talk about transgressive. It’s an offense to the sophistication of coolness. The way she handles color and light is assured and energizing, and yet the outcome invariably looks more animated than alive, like the fantasies she depicts. Is this anything for her to bother herself with? I think not. The market niche she’s cornered probably overlaps a bit with John Currin’s sales region and customer base, and it’s a lucrative one. Her paintings bring six and seven figures now. The only downside to all this is that a masterfully rendered cartoon is still just a cartoon. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. But it doesn’t seem entirely out of line to wish for work where Yuskavage is as secretly invested in the subject as she is in the way she paints it.

Comments are currently closed.