Mindfulness

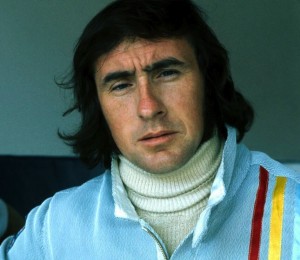

Once again, a non-painter has expressed perfectly, for me, why painting matters. This time it’s the famous Formula 1 driver, Jackie Stewart. I finished watching Martin Scorsese’s excellent documentary, George Harrison: Living in the Material World yesterday. Late in the film, he brings in Stewart because Harrison became close friends with the driver—open-wheel racing was one of Harrison’s diverse passions, and in the movie, Stewart speculates on why this was the case. Harrison had other passions as well, none of which seem to have much relationship to the world of racing: God, cocaine, Pattie Boyd, landscape design, and Monty Python. Yet the ex-Beatle’s obsession with racing seems the one interest most closely related to Harrison’s brilliance as a musician. In the film, Stewart puts it this way:

You’re going very fast. You’re going at the absolute limit of the car’s tires, suspension, and you yourself are right there on the very edge of your own limits, taking it to the finest point. When that happens, your senses are so strong. In my case, I relate it to a real experience where I came to a corner and before I got to the corner I smelled grass. My senses were so sharp, so exaggerated, that a car had gone off the road in front of me, out of my sight. My senses told me there was something wrong. That was grass. The cars should be on the tar macadam road. So I backed off. The millisecond you’re talking about is so small. That’s what, I think, George saw (in me). That is this heightening of the senses, your feeling, your touch, your feel, your gas pedal, your brake pedal, the sensitivity to the function of those. When I talked about that, George loved that. A guitarist, how he can make that guitar talk, that is another heightening of senses beyond the ken, beyond knowledge . . .

The hint of mysticism in Stewart’s description of driving at the limit of one’s ability will ring true of anyone who has gone deeply into any physical activity to the point where the conscious mind steps aside and something else takes over, a larger and more intense state of awareness. Shooting a three pointer. Hitting a perfect chip shot. That heightened state of awareness is what, fundamentally, painting is about. It’s often a function of the amount of time required—hours, days, weeks, even months—the time devoted to just looking at something in order to capture the way light falls on it. Until you can convey what you see, without thinking. Someone looking at a painting can feel the time invested in it. You can almost see time itself, when you look at a Vermeer. What you’re really seeing is a form of meditation, a rich kind of disciplined mindfulness. And that’s primarily what’s conveyed to someone looking at a painting executed in that state of awareness. This same heightened awareness can be conveyed just as effectively in an ink-brush sketch that takes no more than an hour to do, if it’s done with that kind of total mindfulness—after years of learning how to do something with that intuitive and instinctive touch. Iris Murdoch sees this mindefulness as the basis of ethics and moral choice—as well as the foundation of great art. Aldous Huxley simply talks about heightened awareness as an end in itself. Waking up to the isness of things, the nature of what’s real, seemed to be, for him, the whole point of being alive.

Comments are currently closed.