Henry Coupe at Viridian

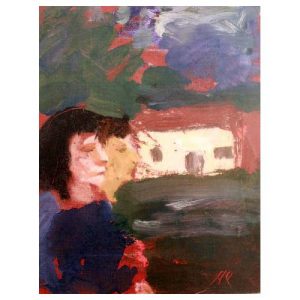

Child at Sunset, Henry Coupe, oil on linen, 10″ x 10″

I’m driving into the city on Thursday to attend the opening of Henry Coupe’s posthumous solo exhibition at Viridian Artists. His wife, Ann, will be there in his stead, since Coupe died in December at a Utica nursing home. I visited with Ann in 2014 at their home and was able to see all or most of the work in this show. She was a gracious host, talking about her husband and his work with great affection and respect. She had arranged all his paintings on the floor of their living room, standing them upright in their floater frames, as if they were our audience rather than the other way around. I sat cross-legged and spent time studying them as she sat on the couch, talking about her life with Henry.

I was a member at Viridian when, shortly after Couple joined the gallery, I first spotted The Letter, one of his small paintings on the shelf behind the greeter’s desk. I immediately asked who’d painted it and learned what little was available about him: that he had studied at the Munson Williams Proctor Institute under Oscar Weissbuch, a student of Hans Hoffman, at the end of WWII, and he had gone on to exhibit his work in New York City during the 60s, while teaching in Utica. He retired from teaching in that city’s public school system in 1976 and continued to paint until he was no longer able to do it.

Viridian offers a lovely description of his work on its website:

Henry Coupe spent his life creating small paintings, most under 24”, executed in strong, simple strokes, of people in landscapes. His people are shown both alone and in small groups. Tiny in scale, his delicate oils are filled with feeling and speak of love, portraying life’s simplest and most important moments, shared with others or experienced in solitude. With simple and direct titles like Girl Wearing Orange Sash or Man Reading, the people in his works are known by nothing more than what they are wearing or what they are doing. We don’t know them, but then we realize perhaps we do, for we’ve experienced that moment of “Listening to Father” or read “The Letter,” while lying on the grass.

It’s difficult to capture why these paintings, which at first glance you’re tempted to think of as roughly executed examples of art brut, are so haunting and arresting. Partly it’s because his sense of color is both bold and yet delicate, with blocks of reds and greens juxtaposed in skillful ways that might jar the viewer, but in Coupe’s work, the colors are so subdued that red conveys a subtle mix of nameless wistful emotions. His use of color and his dramatic simplification of form reminded me immediately of Louisa Matthiasdottir, who studied directly with Hoffman. Matthiasdottir is far more polished and her range and color sense are much more encompassing, but the intense restraint and confined scale of Coupe’s work makes it more personal, more suggestive of a narrative: there are stories here that you will never learn, a letter you can’t read, a bride with a future neither you nor she can discern. Yet many of these paintings are simply miniature portraits, the figures and faces almost unrecognizable, the circumstances irrelevant, because in all the pictures, Coupe evokes a sense of polarity, a tension between human isolation and the comfort of family and friends, with the world of nature offering both beauty and in some ways an intensification of the figure’s solitude.

Ann said that once Coupe discovered German Expressionism, he continued to think of himself a belated member of that group, but his paintings don’t convey the sort of agitation and inner conflict common to that movement. He did begin painting during WWII, yet his work doesn’t seem to sublimate the sort of violent, wartime emotions suggested by the distortions of that earlier work. His paintings are much quieter and in many ways more balanced and carefully constructed. I think Coupe, at one remove, learned more from Hoffman than he gave himself credit for; if you enlarged his tiny paintings to a more heroic scale—in other words to the sort of dimensions a mid-century American abstract painter would have employed—the images seem more at home alongside the work of Milton Avery, or even Rothko. The scale is what distracts you from the abstract expressionist sensibility at  work here. Two People in the Country is composed as a stack of three distinct rectangles, two of equal size at top and bottom with one narrow one bisecting them. The two faces of the figures at the left extend the facade of the house—three faces in a row, as it were—together forming one bright trailer-shaped block of white, Naples yellow and pink. Even the house seems to have eyes and an open mouth—but the feeling here couldn’t be further from an architectural homage to The Scream. The darkest area, on the left, is distinctly defined and curls around that bright middle rectangle to form one head of hair for the two figures. The color is extremely subdued, but in the way he juxtaposes the Indian red, which seems to have been the ground color for the whole painting, against the dull green and purple of the sky and trees, everything comes alive in an unstable and yet tranquil way.

work here. Two People in the Country is composed as a stack of three distinct rectangles, two of equal size at top and bottom with one narrow one bisecting them. The two faces of the figures at the left extend the facade of the house—three faces in a row, as it were—together forming one bright trailer-shaped block of white, Naples yellow and pink. Even the house seems to have eyes and an open mouth—but the feeling here couldn’t be further from an architectural homage to The Scream. The darkest area, on the left, is distinctly defined and curls around that bright middle rectangle to form one head of hair for the two figures. The color is extremely subdued, but in the way he juxtaposes the Indian red, which seems to have been the ground color for the whole painting, against the dull green and purple of the sky and trees, everything comes alive in an unstable and yet tranquil way.

My two favorite paintings in the show, The Letter, and Girl at Sunset, are perfectly done, instances where he found just the right balance between the human figure and its environment. In both, his arrangement of color becomes just as gratifying and expressive as the way he renders the figure. In Girl at Sunset, everything works in perfect harmony, the color, the composition, the brushwork, and even the tiny slivers of pale yellow, at the top of the girl’s head and behind her at the crest of the forest, suggesting the last ray of the setting sun giving her hair a backlit glow before it disappears. There are many paintings here that aren’t as satisfying as his best, but once you’ve seen all the work, you recognize in every painting a passion to honor how paint can make you see and, at the same time, awaken you to so much more than is visible.

This may be the only place you hear about this show, but it’s one worth visiting if you’re in Chelsea before it ends on Sept. 24.

Comments are currently closed.