Get to the Morgan by Sunday

Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver, Rembrandt, oil on panel, detail

I rarely go out of my way to see a Rembrandt. He’s one of those painters you assume you know inside and out. What more is there to know? Yet, every time I spend time with one of his paintings, I walk away almost in disbelief at his genius and his flawless skill. Nothing about Rembrandt’s approach to painting appeals to me, personally: the staging and use of darkness to create cinematic effects, the way in which his chiaroscuro banishes most color from his palette, except in subtle concentrations, and even then it’s usually a world of brown and gray. I don’t live in a world that looks this way unless I’m glancing around a room lit only by the glow of a flat-screen TV. Yet when you stand before one of his great paintings, it’s jaw-dropping and almost dumbfounding. I felt that way in 2014 at The Frick, when I saw Simeon’s Song of Praise, a small canvas depicting a scene that feels enormous, and I had an even more intense reaction last week to Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver, on view until Sunday at The Morgan Library. The two paintings were completed two years apart, the latter when Rembrandt was only 23. How does a kid paint something this masterful, not only in technical skill but in its depth of understanding and empathy? When I saw this painting, it finally struck me that Rembrandt belongs in that cohort of rare, black swans who achieved effortless perfection at the earliest ages: Mozart, Rimbaud, Hendrix, Keats. In the case of both paintings I was astonished, the way I was six years ago when I saw how El Greco rendered the faces in The Coronation of the Virgin in a show at Onassis Cultural Center–overwhelming emotion and thought conveyed in faces that required, at best, a couple square inches of painted surface.

This show is built around only one painting, as the Frick show was primarily a way to offer the public a view of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s show in 2009 offered access to his Milkmaid. In all three instances, the exhibitions were devoted to work on loan from European collections, and they all gave a single painting its own stage supplemented by collateral work that helped put it into historical perspective. Of the three, the Morgan’s is the most effectively curated. More than two dozen drawings and prints line the walls around the central painting, and they are equally exhilarating. It’s one thing to know that Rembrandt was a masterful draftsman, but it’s another to see evidence of his preternatural facility repeatedly, in one drawing and print after another.

In conversation with Lawrence Weschler, for a catalog that accompanied his 2005 watercolor show at LA Louver in 2005, David Hockney rhapsodized about the irrevocable brushwork, the once-and-done, Asian quality of a single Rembrandt drawing, A Child Being Taught to Walk:

Look at the speed, the way he wields that reed pen, drawing very fast, with gestures that are masterly, virtuoso, not calling attention to themselves but rather to the very tender subject at hand, a family teaching its youngest member to walk. The face of the baby: how even though you can’t see it, you can tell he is beaming. This mountain of figures, and then to balance it all, the passing milkmaid, how you can feel the weight of the bucket she carries in the extension of the opposite arm. All of it conveyed, magically. But look at the speed, the sheer mastery. The Chinese would have recognized a fellow master.

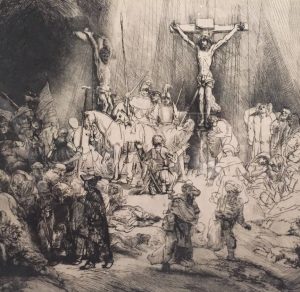

Hockney called it “the single greatest drawing ever made.” This show will evoke the same kind of superlatives over and over, as you move from one drawing and print to the next. One technique Rembrandt  used consistently was to drench a focal point in bright light by doing nothing but line drawings of the figures–outlines, almost cartoons, while rendering everything in shadow with a grisaille of light and dark. At first glance, you think, it’s unfinished, but then you realize that it simply indicates that the shaft of light is so intense that it washes away nearly all the detail in the spotlit figures. The contrast it creates makes the drawing seem even more spontaneous and alive. Ironically, Rembrandt had to fall back on only his unerring sense of line, without modeling, to show all he needed to show when it came to the most crucial individuals in the depicted event.

used consistently was to drench a focal point in bright light by doing nothing but line drawings of the figures–outlines, almost cartoons, while rendering everything in shadow with a grisaille of light and dark. At first glance, you think, it’s unfinished, but then you realize that it simply indicates that the shaft of light is so intense that it washes away nearly all the detail in the spotlit figures. The contrast it creates makes the drawing seem even more spontaneous and alive. Ironically, Rembrandt had to fall back on only his unerring sense of line, without modeling, to show all he needed to show when it came to the most crucial individuals in the depicted event.

Colin Bailey, the Morgan’s director, in an interview with Leonard Lopate, pointed out that Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver went through many revisions as Rembrandt painted. Xray studies of the painting have shown how he changed his mind about the composition even in the advanced stages of his work on it. The intense light streaming into the scene from the left, which is fundamental to the entire image–the light source is what visually unifies most representational images, after all–was a late modification, at least in the way it makes the open Bible the brightest object in the painting and highlights the coins strewn on the floor. Everything in the painting is rendered with magical skill, from the faces of the participants–somehow the likeness of Judas is so distinctly individuated that the tiny features reminded me of Ezra Pound’s profile–to the little bits of glinting chain link dangling from the bottom of the mounted shield or breastplate overhead.

In reference to the fact that this painting has rarely been available to the public, having belonged for years in a private European collection, Lopate asked: “How does someone like you respond to some pretty great paintings hidden away in warehouses? It seems to me to go against our whole idea of what art is about–if people buy it as an investment and keep it in a warehouse as a way of avoiding taxes–Van Gogh, Picasso, Leonardo, works that should be seen. That has to cause pain for someone whose life is devoted to exhibiting.”

Bailey said: “Whatever we think of these warehouses, the works are safe and are not deteriorating, but from the museum’s perspective, public access is something we’re committed to. The depth, vitality of the Morgan is interdisciplinary. It’s an encyclopedic institution in miniature.”

I’m drawn more and more to The Morgan when I come into the city, on the strength of the shows I’ve seen there: William Blake’s work in A New Heaven is Begun, in 2009, the sui generis Emmett Gowin show last year, Hidden Likeness, and now this exhibition. If you want to see the outcome of concentrated curatorial passion combined with deep insight and archival resources, The Morgan is the place to go. From these shows, I come away feeling as if I’ve connected more deeply, not simply with great art, but with myself.

Comments are currently closed.