Insalaco transformation

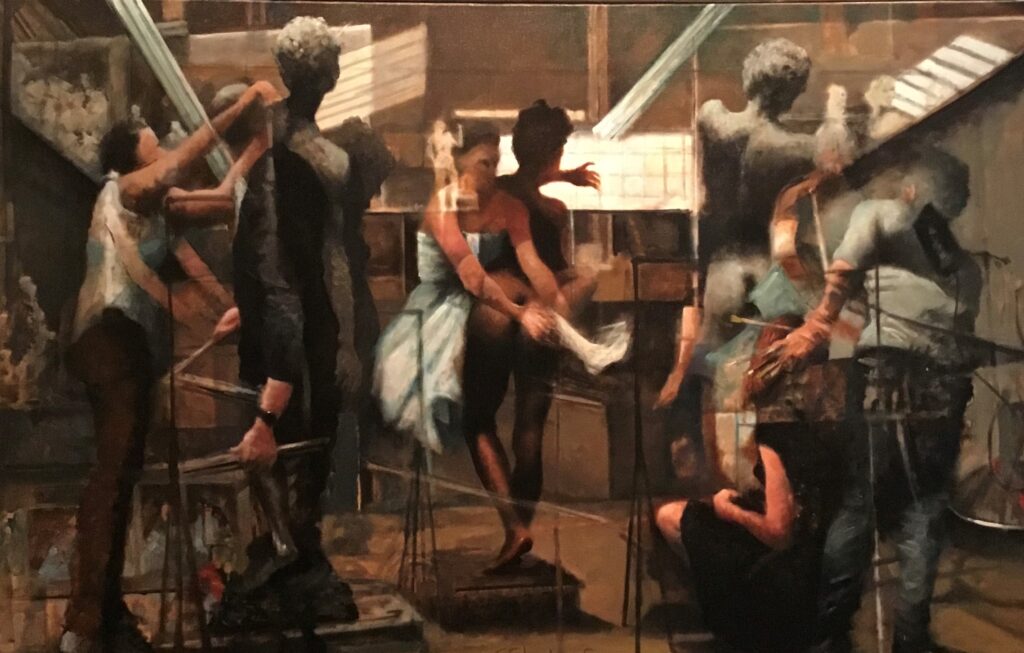

Tom Insalaco, one in his new series of studio paintings

For quite a while now, Tom Insalaco has been working on a suite of paintings that remind me of the world Braque inhabited–both pictorially and spiritually–at the culmination of his career when he was painting abstract images of his studio. Braque spoke in his notebooks about transformation as the essential thrust of painting: to take what’s seen and magnetize paint around the imagery the visible world lodges in your soul. Insalaco has immersed himself in painting after painting of artists at work in various studios, finding sources in films on the Internet and then transforming what he observes into what could be interpreted literally as double-or-triple exposures, scenes superimposed upon one another. But he’s after something outside time and space, indefinable, one’s true life, in accessible to the daily conscious mind. And focusing on the studio as the portal, a window, into this extra-temporal reality, he’s trying to get at why we paint at all. It isn’t to change the world. It’s to witness what’s actually there, everywhere, inaccessible to our chattering, busy minds. Of course, every painter I know and love is trying to do exactly the same thing, but in his or her own way.

Here what appears to be a dancer either stretches or practices in the center of the painting. Layered over this, a remote scene of a performance on stage, a singer or actor, like a remote, lonely puppet, and finally what gives the painting its structural coherence, a studio where two sculptors are working from a nude male model. What’s easy to miss is what appears to be a little quote from Velasquez, as it were: a slightly jumbled hint at Las Meninas, maybe the greatest studio painting in Western art. Insalaco didn’t consciously put that there, but he saw the unintentional reference himself, when I pointed it out. The seated woman in the foreground seems part of the scene with the dancer. Everything melds together into a unity that has its own dreamlike disengagement from familiar time and space, which is Insalaco’s true north, the disorienting transcendence of the surrealists, but closer to Chagall’s ecstatic Cubist-influenced dreams of his love for Bella, his heart’s home, where gravity knocked but never got in. Time here is Proustian, and space is both as small as the amount occupied by a mosquito arrested in amber and as large as the Milky Way.

Comments are currently closed.