I love New York. Again.

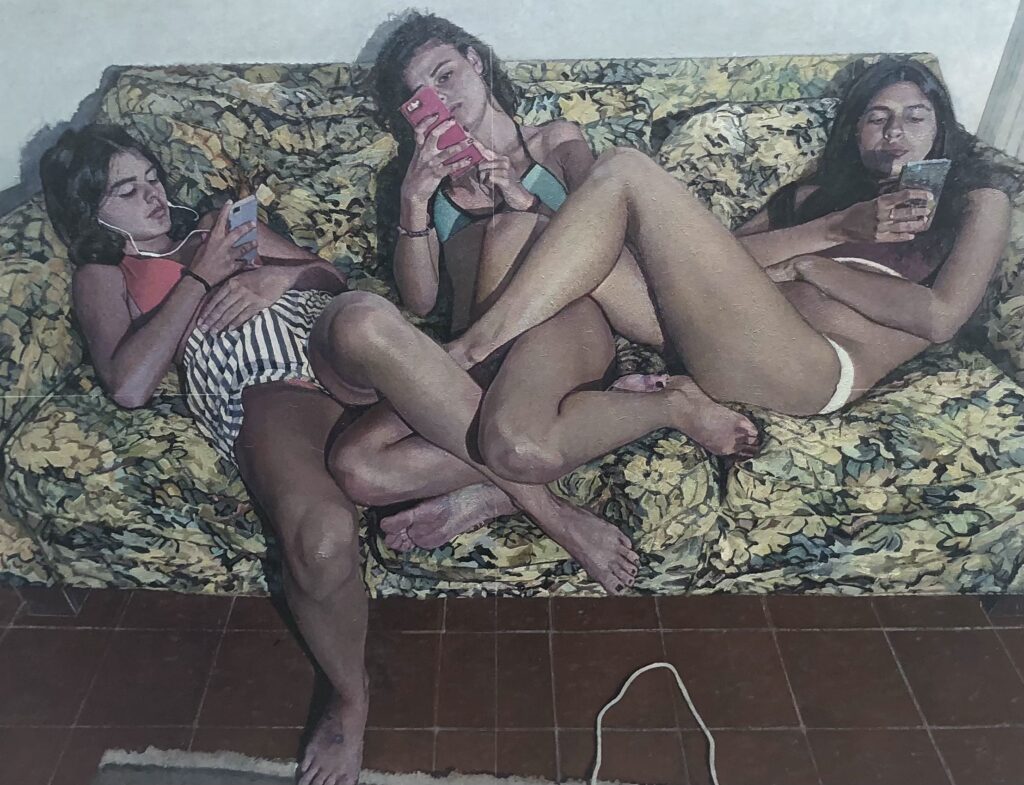

Social Network, Bernard Siciliano, oil on canvas, 2019, 76″ x 100″

I had an exhilarating visit to Manhattan three weeks ago. It’s been a year and a half since I went into the city to see the Salinger relics, as it were, at the New York Public Library. (I have yet to finish a post about that, though it’s nearly done.) The pandemic started a few weeks later and the world seemed to come to a halt. Time stopped. It has restarted. On my weekend in the city, things were hopping, much more alive and back up to speed than I’d thought the place would be. Saturday foot traffic was actually pretty heavy throughout Chelsea and SoHo. Midtown, where I stayed a couple nights, was sketchy and a little weird, as if the idleness of the pandemic drew people into stagnant eddies in alcoves, on corners, everyone just idling in public, harmlessly enough, people discarded by that more purposeful river of humanity to the north and south. Trash everywhere was overflowing nearly every visible container. That New York scene of urine was detectable at regular intervals. A mile uptown, in Central Park and along Fifth Avenue, as well as on the West Side, things seem quietly jubilant and populous.

The galleries were open but not packing anyone in—in other words, back to normal, but with masks. Zwirner had plenty of visitors, but I didn’t want to stick around. Ray Johnson’s solo exhibition was amusing. The motto on the wall as you walked in: “If you take the cha-cha out of Duchamp you get what a dump.” On display in a glass case were some rubber stamps he’d created that made me laugh. With them you could ink some labels onto an envelope or sheet of paper: Collage By A Major Artist, Toilet Paper, Odilon Redon Fan Club. Somebody could make some extra money with an extensive line of rubber stamps in that vein, if people only used paper to communicate now. I spent most of my time at Arcadia, Meisel, Hauser and Wirth, Paul Kasmin and wherever I could find representational painting of one sort or another. Much of what I saw in the galleries I visited was rewarding and, in the galleries I didn’t check out, much of what I could see through the windows seemed clearly avoidable. I caught the last day of the curated group show of figurative painting at Sugarlift, which was the highlight of my weekend. If Sugarlift can make a go of it in Manhattan, after holding its own in Brooklyn, good things remain possible in the world of painting. I rode the elevator up at Pace (what next, an escalator like the ones at Target a few blocks away?) to see the Agnes Martin show, a selection of nearly all-white stripes with only one or two bearing the faintest colors. I felt as I’d felt seeing her retrospective at the Guggenheim. She’s such an enigmatic figure, her abstraction seems intensely personal, cherishing her Platform Sutra, periodically living in isolation, creating one horizontally striped canvas after another, paintings that seem to belong at Dia Beacon next to Robert Ryman. Somehow, though, they are more poetic and wistful, albeit almost as minimal. Why her painting works this way for me, I have no idea, other than the general mystery of painting and what undetectably goes into it and then comes back out. Yet again I was struck by how idiosyncratic her paintings felt, the lines she seemed to have drawn free-hand in graphite to define the stripes, so that the pencil meandered like a lady bug leaving a trail around the little irregularities in the surface, a tiny trickle of graphite (it would appear) that looked serpentine from a few inches away but straight from six feet. Seeing a small collection of her work on view together, the repetitiveness, the sense of slight variations within the confines of a voluntarily apophatic format, gave me courage to keep painting my repetitive images of taffy, seeing where it will lead. (But the work proceeds so slowly, like Issa’s snail. I told Tom Insalaco when I went to see him in his studio last Friday that doing this series takes so much time, it feels like trying to sprint through a swamp.)

My visit to the Metropolitan on Sunday, more than at any previous time, made me feel as if I hadn’t ever understood paintings I’ve looked at many times before, either there or in reproductions. Again and again I thought, I’ve never really seen what was going on in this painting as clearly as I do now. It’s a great state of awareness, to look with that kind of fertile attention, especially in that museum. I spent a lot of my time in the gallery spaces devoted to the evolution of Degas, an artist I’ve begun to admire more and more, though I hardly gave him any attention when I was younger. It was humbling and awe-inspiring to see him grow from a conservative realist to a man who succeeded in getting pastel to do things it hadn’t done before through candid and intimate images of women rendered in long parallel single-hatch marks. But these long lines of color, furrows almost, with the gauzy effect of pastel rather than the crisp marks in a Durer, say, using the tools of drawing or print-making. Those parallel lines that surfaced and receded across the image gave it a vibrating energy, a pulse, that worked in counterpoint to the soft, diffuse light pastel typically gives off. Seeing his transformation from earlier and brilliant academic work to these late, radiant studies drenched in rich color, as I moved from one work to the next, was like watching a caterpillar shape-shift into a butterfly in a time-lapse film.

I had dozens of surprises like that: a Lee Krasner that was reminiscent of Matisse, painted a decade or so before she died; a de Kooning that, up close, revealed that he’d pressed newspaper pages into his gesso, or whatever ground he was using, to leave a ghostly image of the words and pictures pulled from the newsprint, reversed, the way kids once did and maybe still do with Silly Putty; a pair of worn shoes from Van Gogh that reminded me of Heidegger’s famous quote; a vertiginous overhead view of a long table and floor from Sheeler that was part of my inspiration for the series of large tabletop still lifes; one of Braque’s great paintings from his middle period, along with the gueridons, a pool table also seen from directly above, but shaped like an hour-glass; one of the Ocean Parks from Diebenkorn; and maybe my favorite paining from Cezanne, View of Domaine Saint-Joseph, a painting closer to the work of the Impressionists than most of what he did, but with an utterly unique sense of color. He knew how to create a network of marks across a canvas, where every spot of color lives in its own subtle purity, no going-over, no pentimento, once and done, each mark unique—creating maybe the most complex and lovely greens of any landscape ever painted—and yet despite all that energy and perfection in the mark-making, considered on its own, it also serves to convey the humming, brilliant energy of a summer day in the hills. The Metropolitan was full of people. The line for the Alice Neel show was half an hour long, according to the guard. Skipped it, but nice to see things are heating up. All that waiting-in-line patience has been honed by deprivation, probably. On the other hand, the guard told me that shows in the near past have drawn lines that snake out the front door and around the block.

I got the distinct impression that right now might be a rare opportunity for a gallery that wants to open or re-open in New York. For years now, art galleries have had to make more and more money to remain operational in Manhattan. George Billis has left, moving his space to Westport. OK Harris closed a while back, though not simply because of the cost of renting the gallery space. Danese/Corey ended its brick-and-mortar exhibitions, which felt like another Gotterdammerung blow to anyone who longed for islands of sanity and taste in the anarchic and often underwhelming sea of visual art. Five years ago, Steven Diamant packed up and left his gallery in New York to open exclusively in Los Angeles, first in Culver City and then in Pasadena. Both of those locations looked bigger and brighter than the one he’d had in SoHo. He spent five years trying to adapt to California. When I came into the gallery he was in his office, available to visitors as always. I asked about his move back to New York and he said he hated California. I went down the checklist sardonically, after he said he didn’t do yoga. Sushi? Never eats it. Pilates? As if. Charlie don’t surf, and I gather neither does Steve. I found him, as usual, on site in his office, there to answer questions and talk about the show, and his other artists. And this is where he told me some things that ought to signify a little inflection point for the art scene in Manhattan—or maybe a window of opportunity this year, at least. He said that his location is far better than he’d ever had in Manhattan and his exhibition space on W. Broadway at the edge of SoHo is now larger than any space he’s previously had and yet the rent is lower than what he paid twenty years ago.

People should be flocking back and locking in long leases. In major cities and across the country, the real estate mania is driving inflation in housing prices—even as commercial real estate looks more and more like a graveyard for burying cash. The pandemic drove people out of the cities, many of them for good, and is still driving them out, because so many city dwellers learned they can work remotely. Offices are emptying out. The pleasant surprise is that, commercial real estate is getting cheaper. It would seem to be the time to get a deal and open galleries like Sugarlift, dedicated to genuinely good new art, for those who love good art, rather than investors seeking an alternative to precious metals. To put it precisely: do all the gallerists out there realize that this represents an opportunity to move back into a prime location at a much lower rate than before? This undoubtedly won’t last, with all the money the government is pumping into the economy. But, as the city opens back up, maybe some galleries can move back in.

Comments are currently closed.