Archive for the 'Uncategorized' Category

April 9th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Lifecycle IV, detail

This morning, the New York Times has a story on how, in the late 50s and 60s, the Ford Foundation became, essentially, a central patron of creative work for struggling artists in the U.S. The story quotes from letters James Baldwin wrote to the foundation, asking for funds to help him keep writing, and then goes on to explain that he used the money he was awarded to support work on Another Country:

It was 1959, six years before Congress created national endowments for the arts and humanities to support struggling artists and cultural institutions. For Baldwin, who was straining to finish a novel and pay personal debts, the place to turn for cash was neither the government nor any literary agent but to a relatively obscure foundation official named W. McNeil Lowry. Mr. Lowry had the last word in deciding which artists, writers and performers would receive grants from the Ford Foundation, the richest private source of cultural largess at the time. This month letters to and from Mr. Lowry . . . were opened to researchers at the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, N.Y.

There’s nothing unusual anymore about getting a grant to make art, but the focus on the personal, informal-sounding letters asking for a gift of money struck a chord, mostly because my friend Rush Whitacre, at artist in Brooklyn who plans to move home to Ohio soon, has been writing exactly the same kind of letters to unsuspecting potential patrons over the past few months. Currently, he’s writing to Jerry Bruckheimer, the movie mogul, asking Mr. Bruckheimer to please pay off Rush’s college debt in exchange for the gift of Rush’s best painting, an enormous canvas of sunflowers inspired by Van Gogh. (This letters project was also inspired by Van Gogh’s letters to his own patron, his brother Theo.) Most artists I know, like Rush, have little money to support their work, and—like Rush, who works as a security guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—have other jobs to pay the bills, leaving little time left to actually create art. Rush has never met Mr. Bruckheimer, and undoubtedly never will, but this doesn’t stop him from writing a daily letter—as well as a poem—imploring the producer to dip into his exceedingly deep pockets and become Rush’s patron.

Rush’s audacity never fails to amuse me—especially because it’s almost More

April 5th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Gary Lee Cordray

I read an extremely funny book yesterday: Bad Ass Art. It was written and self-published a couple years ago by Gary Lee Cordray, as his thesis project for a degree in art at Ohio University. It lays out essentially how to become a Bad Ass Artist, a process that begins by rolling dice in order to determine all the elements you need for your work to add up to a score of either +6, +12, +18, or +24, in the Bad Ass Art-Making system. Or if you already have an idea for a work of art, you can calculate how all the work’s elements add up, and then modify your notion so that you get a score which is a multiple of 6 points. (You don’t need to understand this. I don’t. I don’t think Lee wants you to.) There are four levels you can attain, the lowest being Badass Art. Next up, Fine Art. Then, Badass Fine Art, and finally, at the highest level, High Art. A few examples of how to score your work by identifying Bad Ass elements: Big Watery Eyes, +1; Jars, Bottles or Urns, +1; Glowing, as if Magical or Divine, +1; Bar codes, pills, or price tags, +1; Realistic-looking or lifelike, +1; Part of a coherent series or body of work, +1; Big sharp teeth/fangs, +1; Reflections, +1; Add wings, +1, and so on. The list of elements runs to 80 elements in four categories: Dark, Weird, Sexy, and Artistic. To be Bad Ass, a work needs to draw elements from at least three categories. There is no justification for any of the scoring rules, of course, but as you thumb through it, the prose lulls you into nodding and adding up numbers from your own work, thinking, huh, OK, that canvas I finished last week, hm, three, four points, no, five. No! Only five! OMG. Fail!

The opening of the book has it’s most rewarding voice:

“Welcome to Bad Ass Art; a mode of art making that has set many artists free from thinking too hard More

April 3rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

From one of the most trustworthy critics, in the NYTimes, commenting on Morley Safer’s piece about the world of art on 60 Minutes:

“Have [the super-rich and speculators] ruined art? No, they’ve just created their own little art world that has less and less to do with a more real, less moneyed one where young dealers scrape by to show artists they believe in, most of whom are also scraping by. Mr. Safer should visit that one sometime, without the cameras, and try to see for himself, beyond the dollar signs. Either that or he should just come clean: He could not care less about the new or how it makes its way, or doesn’t, into the world and into history.”

–Roberta Smith

Arthur Danto might argue against “the new” and suggest that art history is over, but Smith is absolutely right about where someone ought to be looking for the real struggle, and how the artist’s old companion, despair, is a lot more prevalent than big money wherever that effort is taking place.

March 28th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Without elaborating much, this is a conversation I had via email with my cousin, a retired Washington D.C. attorney with an encyclopedic knowledge of film, and his friend from Kenyon College, Dave Roberts, who is an expert on math. We were trying to figure out whether or not there are random elements in great art, whether they matter, and then, eventually, whether or not art is fundamentally about “newness” or about something else. I also got sidetracked onto the subject of freedom and free will. Somehow all of this seems tied together, but I have a hard time connecting the dots. When Brian veered toward his distinction between “newness” and fundamental value, in creative work, he got close to what seems to matter quite a bit in the world of visual art right now, to the detriment of quality. Over the past century, the world of visual art has idolized the New, and Brian’s unabashedly ultra-conservative position on the world of film, in particular, is that this has done almost nothing but corrode the intrinsic value of the art form. Godard is something of a villain in Brian’s world. For him, substance is all that matters, and that substance—story and character, essentially—can be as old as the ocean. Newness is beside the point. Yet, the way I look at it, when you see great work, you have a sense that you’re seeing something for the first time, and that feeling of freshness, of seeing something anew—that’s a component of creative experience that’s essential to what art is. It means the work is alive, and you’re alive. Define that word “alive”, or that feeling of “new” for that matter, and you’ve unpacked all these issues and made them clearly understandable, but that’s a tough job. I’m just not sure how great art works, what it ultimately “means”, why it seems to be impossible to mechanize—and what all these questions we explore here actually mean in relation to human behavior and human experience. But I’m pretty sure the best art tries to manifest what it means to be alive and it involves all of these issues we were addressing.

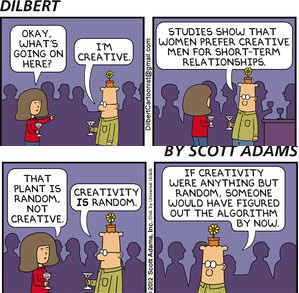

Brian: I don’t read the comics as regularly as I once did, but last Sunday’s Dilbert caught my attention. In it, Dilbert espoused the following theory More

March 21st, 2012 by dave dorsey

Soren Kierkegaard

When I was in my mid-teens, one night, I was seized with the classic existentialist question: why is there something rather than nothing? It was a bit more complex, and the experience I had felt more like a frightening recognition than a question, but that was the heart of it: along with a sense of absolute certainty that there was no possible meaning to anything in life. It was as if I’d stepped out of our back door into the Void. Anyone who has been seized with this kind of questioning knows how overwhelming it can be. Those who haven’t been obsessed this way will probably scratch their heads and point out that the question itself hardly means anything. What possible answer is there? But that’s exactly the problem, when you are consumed by this overwhelming hunger to know “why” you are alive.

I was reminded of this recently when I came across a little meditation on anxiety in The New York Times, in which the writer quoted the Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard:

Though he was a genius of the intellectual high wire, Kierkegaard was a philosopher who wrote from experience. And that experience included considerable acquaintance with the chronic, disquieting feeling that something not so good was about to happen. In one journal entry, he wrote, “All existence makes me anxious . . . the whole thing is inexplicable . . . “

I thought: that little sentence I’ve boldfaced pretty much nails it. That’s exactly what I went through. So for several years in my teens all of life seemed meaningless, pointless—but not depressing. I wasn’t depressed at all, not in any clinical sense. Good appetite, decent grades, went to the prom with Cindy Bethel. Got into college. But life seemed like Shakespeare’s tale told by an idiot . . . signifying nothing. I looked at everything, good and bad, beautiful and ugly, just and unjust, life and death, and I thought: what’s the point? Not because I was frustrated or disappointed. It was as if I’d been knocked completely out of all my ordinary frames of reference and was, in an anguished way, trying to remember what had once seemed so compelling about getting up in the morning. I had no urge to die, or otherwise escape this state of limbo, because I knew there was no escape. The escape would have been just as empty as what I was fleeing. It wasn’t that I was upset about injustice or America’s materialistic values or our involvement in a foreign war or how hard it was to make a left turn into the village Starbucks. (If there’d been a Starbucks back then.) Nothing made sense. Yet this is when I started getting serious about painting.

A year or so earlier, I’d found some small starter oil paints my father had More

March 18th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Four Plums

Four Plums is an oil-on-linen still life I’m going to show in the fall at Oxford Gallery, in a two-person show, the first I’ve had there. It’s the sort of thing I want to keep doing as I build a portfolio of work specifically for that show. I’m under the gun a bit, yet I’m changing the way I work as part of my effort to present the best work I can do. I’ve replaced some economy paint with a more expensive line, and I’ve noticed a real difference in the way the paint handles, but I’m still not sure if it’s the quality of the paint or simply the fact that it’s new. The other tubes were getting old, since I use fairly thin layers of oil and a tube can last me years–if it’s a color I don’t favor. If it’s several years old, it thickens and gets harder to use without some dicey thinning. Yet buying the new paint, using better materials, was only part of a larger commitment I’m making to this show in the fall. I’m also resigning myself to taking whatever more time than I might have devoted in the past to finishing a painting properly. What I’m finding is that when I surrender to the natural pace of a given painting, as a way of committing to the best possible outcome, the act of painting will flow the way it should, and I’ll feel more secure about the results as I paint—because I don’t move forward until I’m satisfied with the work I’m doing at the time. I might go back to that area again and again, but if I’m as careful and accurate with it as I can be, from the start, it sets me up for more effective finishing touches later on. I’m not saying I was doing rushed work in the past, but sometimes I would ignore frustration and plow ahead, forcing things, instead of listening to my reactions. I guess all I’m saying is that I’m working in a way that feels more natural to me, rather than trying to paint with a method some other painters I know are using.

There’s some deep connection between the tactile feel of applying paint, in a way where each brush stroke brings a little ping of satisfaction, partly because it’s so carefully considered, that conveys some hard-to-quantify freshness and life in the finished work. It doesn’t make much logical sense that the feel of the activity results in a more convincing look, but that’s what I keep discovering, over the years, and then repeatedly ignoring, when I’m under pressure or impatient to be done. I am putting myself under a self-imposed deadline here, which motivates me to work faster, because I’m hoping to contribute a couple dozen paintings to the show, which means, ideally, I’d like to create maybe eighteen new paintings. I’ve already finished a few, but I still have more than a dozen to paint between now and September. I can do the math and I know how much time I have for each one. Yet it seems that I need to forget the deadlines and try to do only what a good, careful pace requires, which threatens to slow me way down. Here’s the paradox, in the image I’m working on now, of a ceramic bowl, when I slow down and forget about how much of the image I want to finish on a given day—and just focus on getting every stroke done properly, every color applied after long consideration—I begin to see how what I’m doing in one area can be duplicated in another, I spot parallels between a color or value in one part of the object and other parts, and I find myself getting more done than I expected. By ignoring the clock, I discover efficiencies that actually save time. By slowing down, I speed the process. Not always, but I seem to remember a line from the band Genesis back in the 70s: you gotta get in to get out. Something like that seems to be operating in this surrender to the required pace of the work.

March 16th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Molly Crabapple with Great American Bubble Machine

Bob Cenedella would love this. Illustrator and fine artist Molly Crabapple is using Kickstarter to fund her political paintings. It’s a way of doing an end run around the galleries, the collectors, the whole apparatus of how the art world rolls forward. It’s a great idea, partly because she spins off from each project a line of small novelty items and even gives her lesser contributors artifacts of the process itself: old brushes, a used palette, preparatory sketches, or little tchotchkes adorned with little drawings. Or, if you can’t give much, you simply get access to what she’s up to at particular times. It’s a bit Warholian, a way of turning the process of making a painting into a business with investors, and yet it doesn’t reek of cynicism or greed. She wants to get the work done without being beholden to anyone or anything other than the idea that drives the work. Still not clear on who actually gets the one big painting that spawns all the other items, if anyone, but for her latest project she’s raised more than $50,000. Take that, Chelsea. This isn’t for everybody, or even most of us–does she have a staff of elves to make all this “merchandise” for investors? And it does seem to veer queasily close to the capitalist business model the movie industry uses to generate merchandise from a summer film. Yet it’s an interesting way to make a living doing good-hearted work. I like her attitude too. She’s serious but she keeps it unpretentious:

Is Shell Game dirty commie pinko propaganda?

Maybe a little. But you’ll find the same scampering fat cats, tentacles, and surreal details that are always in my work. So my fans who could care less about world affairs should still like it.

March 14th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Eric Fischl, Christie Sitting in Neil's Truck

The Eric Fishl show at Mary Boone is both repellent and wonderful, though not at the same time, and not in the same measure. You walk in to see a large interior with a man in a business suit bearing up a naked woman, reclined on his lap—as if he’s offering her to the viewer on a platter. It’s a masterful image, wonderfully painted, but it’s also routinely startling, in Fischl’s de rigeur way, with creepy and intriguing sexuality. I lingered there on the way out, I’ll admit it. As Ken Johnson put it in The New York Times:

A painting in the foyer of Ms. Boone’s Chelsea location is woefully emblematic. Based, like all his portraits, on a photograph and painted in Mr. Fischl’s signature, lushly sensuous style, it pictures the model, actress and artist Anh Duong lying naked across the lap of the elegantly dressed Simon de Pury, the auctioneer and co-star of Bravo’s reality television series “Work of Art: The Next Great Artist.” A blasphemous Pietà, it flaunts a sophisticated but pointless decadence.

The painting is visually powerful, but is this sort of thing really shocking anymore? If he’s trying to remind us of Manet, he does, but he doesn’t fare well in the comparison here. This is Fishl’s familiar trope, sophisticated decadence, and it makes you wonder why he puts so much effort into such elitist imagery: until you see all the red dots at the front desk. Much of the show has a similar creepiness, but from a different direction: it’s as if he wants to show how blissfully oblivious the “one percent” still is, partying on the beach, clothed or otherwise–but these are his friends right, so are they supposed to see how superfluous they look in these pictures? Or else he’s showing how beautiful and cool our media celebrities still appear, in their private lives, even when they sit in an unforgiving shaft of sunlight. I mean, is he just trying to make us all feel even more miserable for having to struggle to make enough money to pay our bills?

Yet, if you hunt in the back room of the gallery, you’ll be rewarded at least once. I didn’t start writing this post to grumble, but to lavishly praise one painting I saw hidden back there: Christy Sitting in Neil’s Truck. It happens to be the first image you see at the Mary Boone page promoting the exhibition, so I may not be the only one who thinks its far superior to the rest of the work.

I loved it primarily for its loose brushwork, nothing overworked, nothing belabored, just a liquid pool of color that seems to eddy and flow into focus, without distorting the image much, showing you an ordinary-looking woman in a truck, gazing into the sunlight toward the camera. She’s probably another of Fischl’s important friends, but this scene doesn’t seem to expect or require you to know it. It captures the feel of the snapshot that served as its source, without slavishly reproducing the image, so the painting is full of life, and because of the way the vehicle creates blocks of color, the image’s abstract qualities strengthen its power. I stood there gazing at this painting wondering why Fischl doesn’t venture outside his economic strata more often and put his amazing skills to use capturing more scenes like this, letting his clear love of color evoke the kind of ordinary, mundane, but beautiful moments all of us experience: light filtering through trees, sunlight on a friendly face, the plaid pattern in a woman’s ordinary wool sweater, and the shimmer of a newly washed red truck. It doesn’t seem to depict someone laden with assets or fame. Been there, seen that, nothing extraordinary going on—and that’s what’s so wonderful about looking at such a moment, with fresh and attentive eyes, through the medium of paint.

March 13th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Zimoun: Volume

After most of my posts, my friend Walt, an amateur photographer who has a great eye, usually checks in to point out typos and grammatical offenses, and generally gives me some idea what he thinks of the post. Walt’s a college grad, an excellent writer and has a consistently funny take on most of the world. In other words, he’s a very sharp dude who appreciates art. After my latest post on the show at Zwirner, he pointed out some awkward sentence constructions and that was it. I could tell he wasn’t too charmed by the work nor persuaded by my writing about it. I didn’t pursue it, but in an email exchange today he brought it up again. The conversation circled around the issue of how broad the definition of art has gotten and how it so often creates work that communicates, if at all, with only a small group of people. It was in some ways an extension of a conversation I had while staying with Rush Whitacre and Lauren Purje and Krystal Floyd in Brooklyn, a week ago: after a tour of openings earlier in the evening, Rush and Lauren and I were debating the BS quotient in a lot of contemporary art, and Rush was defending the right of artists to do nearly anything to create a memorable experience, which was interesting because his BS alarm goes off quite often while walking through Chelsea, in my experience. Walt’s opinions came from the other end of the spectrum.

Walt: Finished watching Herb & Dorothy. Has a charm to it, as a portrait of this couple and I liked the look at the NYC art world. But as far as art goes, I have to admit I don’t get it. What they saw and what you write about is a mystery to me.

DD: Really? Everything I write about?

Walt: No, what I mean is when I have a sense of the art then your take on it is enlightening and makes sense More

March 9th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Jesus, in razor wire

There’s another week left to see Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf, an installation involving various media—sculpture, drawing, video, and, well, taxidermy—at David Zwirner. It’s the latest from Adel Abdessemed, an Algerian artist, whose past work has aroused the wrath of animal activists. This show might irk them as well, though it’s not clear that he abused any living creatures in the process of putting it together. The installation is mostly about how we turn our own worst impulses into a trophy of victory, and it revolves around issues of the relationship between violence, power, entertainment, and the natural world. That’s a lot of ground to cover coherently, but coherence isn’t the goal here—instead you get an eerie and strangely serene impression of beauty as you move through the exhibit, which raises questions about how people condone and hide from the reality of violence. Abdessemed has created a series of horrific images, representing the worst aspects of how human beings inhabit their world, and yet has managed to invest them with a beguiling, if occasionally slick, sense of economy and formal perfection. The show is unfeeling, impersonal, cerebral, and yet gorgeous. If that series of adjectives doesn’t make you uneasy, then you aren’t paying attention to the show. How he achieves this kind of visual charm in, for example, an enormous assemblage of actual animal carcasses is a bit of a mystery, and that’s what’s disturbing and riveting. You don’t want to look away when you should be averting your eyes with disgust. Anyone familiar by now with something called the Internet shouldn’t be surprised to feel those opposing impulses at once.

As you walk in, you see a boat, found abandoned in the Florida Keys, that previously held refugee immigrants. He has filled it with stuffed garbage bags. (I hear an ironic take on: Bring me . . . the wretched refuse of your teeming shores.) Next, there’s a resin sculpture that depicts a head-butting incident at the 2006 World Cup in Germany, which seems to coalesce nearly all of the concerns of the More

March 9th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Armory Show, 2012

Some fun, big-picture reflections on the current Armory Show can be found today from the New York Times, starting with the idea that art is an intelligent virus that propogates itself through the work of artists, without any clear indication of why. That sounds just about right. And a nice passage on how the resurgence of painting hasn’t slowed down:

There is a ton of painting here, and it is all over the place in stylistic terms, from the postcard size, photorealist pictures of nondescript suburban homes, stores and roadside signs by Mike Bayne at Mulherin to the big, colorful, Pop-Expressionist canvases of Bjarne Melgaarde at Greene Naftali. Painting is far from dead; it just does not feel the need to progress linearly, and that is a good thing.

March 6th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Maira Kalman

From a blog by Lori Pickert, a question for Maira Kalman from her eight-year-old son:

(Jack’s Question:) What do you weigh? Just kidding! What is your secret for drawing?

My secret for drawing is not a secret. It is sitting down and drawing. I do the best I can which means I try not to do it right but just to do it as I feel and as I see.

Getting it right is not a good goal.

The biggest secret is perseverance. Just not stopping no matter what.

Though I do stop to run and play tennis so I won’t weigh too much.

But that is a whole other story.

I do everything I do because I love to do it, even when I worry or am confused or slightly in despair. Those feelings usually pass. And then the next day is there.

Always a good thing. The next day.

March 3rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

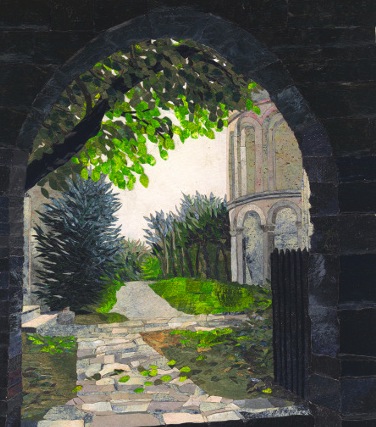

Blinded by the Light

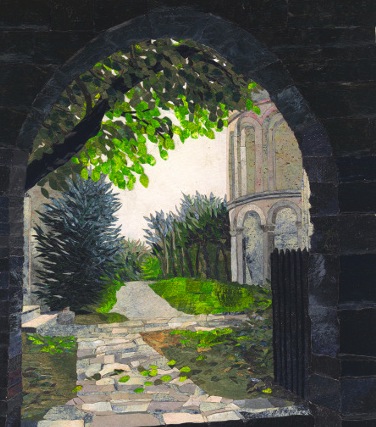

If you want to see yet another way obsession gives birth to beauty, check out the work of Mary Wells at Viridian Artists, a show that runs through March 10. After a visit to Rome, where she discovered mosaico minuto, the art of glass mosaic—images constructed of tiny colored glass filaments—she came back home to Portland, Oregon and invented a way to do it with tiny fragments of paper. The resulting work is as intricate and luminous as a magnified photograph of the scales in a butterfly’s wing. What’s most amazing is how, working from her own photography, she’s able to evoke the light of different seasons. The work depicts scenes from two locations in Italy—the Villa Vignamaggio, ostensible Tuscan birthplace of Mona Lisa, and the cortile of the Ducal Palace in Mantua.

Working from her photographs of the Villa Vignamaggio during each of the seasons, offering a visual representation of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. Her pace allows her to complete no more than a square inch per hour, so the four panoramas, begun in 2008, were completed earlier this year. Each one contains 70,000 paper tiles. The smaller mosaics in the show offer smaller views of the same villa: gardens, flora, vistas and architecture. An additional triptych combines mosaic and painting, with a scene, rendered in cut paper, framed by a painted image of a window flanked by pillars. To complete the work in this show Wells relied on three residencies over the past two years at La Machina di San Cresci in Greve in Chianti, Italy.

I sat down with Wells at Viridian today for a conversation on her work:

DD: How did you learn this technique of assembling cut paper? More

February 24th, 2012 by dave dorsey

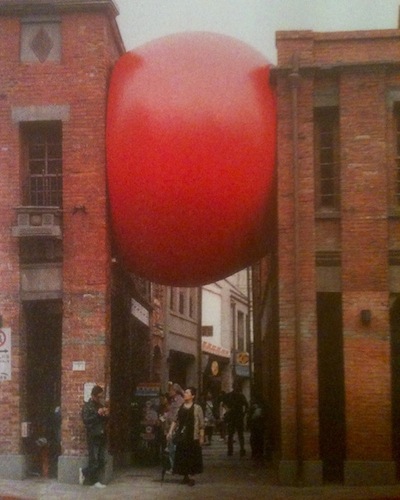

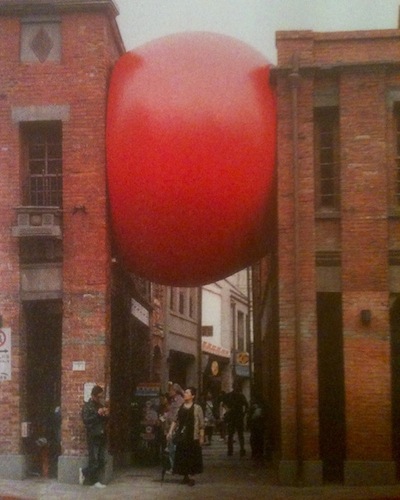

Red Ball Project, Taipei, from Time magazine

Love this, don’t know why. Not sure I would call it art, but still. Like life I guess: it’s caught between a hard place and a hard place. And yet it looks so snug and supported by all that pressure. Ah, if only I could feel the way this ball looks. I think I want one in my area code.

February 24th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Simon Cerigo photo courtesy Martin Bromirski

I ran into Simon Cerigo as he did his rounds Thursday at Viridian Artists in north Chelsea, attending 15 or more gallery openings, who knows how many, that evening—he cruises through more than 60 a month, maybe more, constantly looking for the pleasant surprise. He does it all for his clients, who come to him simply to know what to buy before anyone else knows it. Sometimes they listen. Often, they don’t. The last time I saw him I told him I was knocked out by the Michael Borreman’s show at Zwirner, which I’d seen that afternoon, and he dismissed it with two words: “Too finished.” I found it funny and intriguing, that response. I was hooked. I wanted to hear more. (My impression of Borreman’s technique is that it’s never too much, but always just enough—in terms of amount of paint, brushwork, subject matter, you name it.) So I wanted to run into him again and was delighted when he walked into the gallery. He was wearing a bright orange stocking cap, which a friend of mine calls “a hat even gravity doesn’t understand” because of the way it floats around on Simon’s head, and he smelled just faintly of marijuana—a scent that always makes me feel eighteen again, ready to stay up all night, which actually I did, though without smoke, or anything else, to prop me up. He held forth on the current art scene with precision and insight and had a lot of fascinating things to say.

Simon: The new Koons show, the dot paintings. Ultimately it’s Internet art. The whole show revolves around the Internet. This interactive, multi-locational situation and besides that if you follow Hirst’s work and his market, the dots were considered very glib, throwaway at first. Nobody liked it. It was a half-baked idea. Jay Joplin, this dealer at White Cube, he said enough with the sharks, make some paintings, I’ve gottta sell some stuff. So he rolled out the dots. I met Hirst at the opening, his wife was wearing a hat with a little dot painting on it. He was so stoned. I asked him, what were you on when you did these? He knew I was kidding him. Brilliant showmanship. If you’re going to one-up Koons or anybody else, do it big!

DD: Which opening did you say you crashed back in the 90s?

Simon: The Hirst opening I attended at the Michel Cohen Gallery was the medicine cabinets, very valuable, always considered very important, glass, with pills, the More

February 22nd, 2012 by dave dorsey

The Sound of Noise

“Some things will be illegal, but it will be one hell of a work of art.” –from The Sound of Noise

The Sound of Noise gets it’s U.S. release in March. Can’t wait.

The sound-and-image anarchists behind Music for One Apartment and Six Drummers, the 2001 cult short film, successfully transfer to a larger arena in Sound of Noise, a delightful comic cocktail mixing a modern urban symphony, a police procedural and a love story. The up-tempo feature debut of Swedish directors Ola Simonsson and Johannes Stjärne Nilsson boasts the most complex and wacky musical numbers since Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Delicatessen, hitting notes alternately silly, raucous and rhapsodic. The narrative revolves around police officer Amadeus Warnebring (an engaging Bengt Nilsson), tone-deaf scion of a distinguished musical family, and his attempts to track down a group of six guerrilla percussionists whose public performances are terrorizing the city. The drumming set pieces correspond to an avant-garde score in four movements. Where the short film had the six drummers imaginatively using standard apartment furnishings as their instruments, the feature unleashes them on an unspecified city’s civic and cultural institutions. “Doctor, Doctor” plays out in a hospital operating room, literally removing the sound from a windbag patient; staged like a robbery, “Money” makes beautiful music from a bank’s paraphernalia; the classical music establishment comes under attack from heavy machinery in “Music;” and daredevil “Love” unfurls in midair on the city’s electric lines. There is even an amusing backstory for each of the soberly dressed drummers and investigator Warnebring, their music-hating nemesis.

—San Francisco International Film Festival, Alissa Simon

February 20th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Vernita N'Cognita, Invisible Woman

I drove to NYC Thursday to attend Vernita N’Cognita’s performance of Invisible Woman, at Viridian Artists. I’d spoken with her previously about her work, which focuses on the experience of women in contemporary life. I was especially interested in this performance because of its resonance not simply for women but also as a metaphor for Vernita’s life as a visual artist—and, by implication, the lives of most visual artists. I also felt compelled to see the actual performance, as a gesture of support, rather than watch a video of it on YouTube, because she had been hospitalized for ten days last month, with a rare blood disorder. Her treatment at New York Presbyterian involved five plasmapheresis treatments, where her blood was routed outside her body to remove and replace all of her plasma. In a conversation with a friend of mine, I heard about Vernita’s weakness—having lost ten pounds from an already waif-like frame—and her fierce determination to go ahead with her performance, regardless.

“I have a new hero,” my friend said.

N’Cognita’s work is rooted in butoh, a Japanese art form that began in the 50s when two dancers created it as a rebellion against existing traditions. It relies on exaggerated and slow physical movements, superficially similar to tai chi. More

February 18th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Day 2, Seattle to Rochester

My friend, Jim Mott, the itinerant artist who does paintings in exchange for room and board, has begun a blog where he’s posting a day-by-day account of his 2007 drive from Seattle to Rochester. http://mottart2007.blogspot.com/ What’s wonderful about the way he’s presenting his story as a plot is that you get to see the paintings he did, on the spot, as he wandered across the country, absorbing his surroundings and turning them into the currency of his journey. Here’s a sample from one of the earliest posts, describing an experience most honest painters will corroborate, no matter how masterful they’ve become:

What I won’t tell the class is how uncomfortable painting makes me. Maybe I’m just lazy, but I find painting to be almost prohibitively strenuous, especially emotionally. There’s the strain of trying so hard to capture or convey something I see that interests me, without really knowing how to do it. It always feels that way: like I don’t know how to paint. And I rarely like what I end up with, at least not at first. Yet it seems important to do, and after the painting’s been finished for an hour, a day, a week, a year, I can usually see that something important came through, enough to have made it worthwhile. Enough, in fact, to make me not want to let go of the painting. At any rate, in the end it feels worthwhile, and that’s what keeps me going. But I almost always have to overcome a lot of resistance to get started, especially since stopping to paint something usually means two or three hours locked in struggle instead of two or three hours spent doing something more practical or pleasurable – such as wandering around looking at other things.

It’s so encouraging to hear such familiar doubts and resistance from someone who clearly knows how to paint.

February 12th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Cheers to McSweeney’s. In what is essentially an homage to Jim Belushi’s skit as a chess coach on Saturday Night Live in the mid-80s, Oyl Miller modifies the premise for a witty satire of the current art scene. My favorite line from Big Hank Bricklaw to one of his students: “People have to think there is something wrong with you.” There’s plenty more where that came from. Here’s a sample that hit home for me, someone for whom the still life never ceases to lose its appeal:

What the hell are these still lives? You’re just going through the motions with your painting, kid! These are high school level art class toss offs. You wanna make it to the kind of cutting edge galleries whose walls are bare and only open to B-list celebrities on Tuesdays at three in the morning? You think a smudgy pastel rendering of an inoffensive, submissive, realistically colored little peach is your ticket there? What if it were rotten? What it if had a deformed arm sticking out of it? What if it had dinosaur fangs that represented capitalist desire? These are exactly the kinds of thoughts real artists think. Do you even think? You need point of view in your work rookie. The artwork needs to drip with your disturbing vision.

February 10th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Velasquez, The Surrender of Breda

When anyone speculates on who might be tagged as the greatest painter in Western history, Velasquez always finds himself at or near the top of the list. And Las Meninas is always ranked as the Spanish master’s greatest work. But The Surrender of Breda is in many ways a more awe-inspiring technical achievement, an incredible fusion of artistic influences, an enormous canvas, twelve feet wide, in which a numbingly complex and protracted conflict has been simplified, unified and turned into an ironic image of tenderness. Velasquez takes what James Joyce called “the nightmare of history” and transforms it into a vision of warmth and humanity. At the same time, he’s also representing a small act of courtesy as the best we flawed creatures can hope for: kindness, compassion and humbling gestures of respect in the midst of the world’s ceaseless carnage and cruelty. And there’s a second universal truth here, maybe not entirely intended, given the reality of historical events that ensued: with the passage of enough time, all our victories are Pyrrhic.

Spain lost Breda only a few years after the surrender and went on to lose the entire war in 1648. This moment in 1625 was only a brief setback for The Netherlands. From here onward, the declining Spanish Hapsburg empire gradually ceded its primacy on the world stage to another rising imperial star: the Dutch. This brief, temporary victory for Spain followed a rogue siege of the town, unauthorized by the crown, organized and executed by a remarkable general: Ambrolio Spinola. The Surrender of Breda celebrates how Spinola forced surrender from an equally esteemed Dutch commander, Justin Nassau. Spain had been steadily losing the Eighty Years’ War against the Netherlands, which had begun two generations earlier, at the end of Pieter Bruegel’s life, who depicted the early days of the conflict in his own historical paintings in the Low Countries.

No other painter in history was better situated than Velasquez to paint the life of empire and the tenuous nature of political power. It’s always amazed me how securely Velasquez was installed inside the court of Philip IV. He was never at a More