Archive for January, 2015

January 30th, 2015 by dave dorsey

An Anniversary, Edwin Dickinson, Oil on Canvas, Albright Knox Art Gallery

From Matt Klos, I got the notice below about a couple exhibits of perceptual painting which I’ll be heading down to see in Maryland next month. The first show is a must-see, if for no other reason that the fact that it’s a chance to see An Anniversary, by Edwin Dickinson, which is in the permanent collection in Buffalo at the Albright-Knox. Matt was able to wrest quite a few paintings like this from various sources to put together this overview of how perceptual painting has evolved. I discovered it by chance a couple years ago at the Albright Knox while wandering through its permanent collection after having lunch there with A.P. Gorney. But since then, it has been in storage whenever I’ve been there. While down in the Baltimore area, I’ll spend some time talking with Matt about what went into curating what looks to be such a great show. Can’t wait. The announcement from Matt, including details on a second show of contemporary painters, including his work:

Exhibition 1, “A Lineage of American Perceptual Painters,” curated by Matt Klos

A Lineage of American Perceptual Painters, January 15 – March 1, 2015

This exhibition of American Perceptual Painters focuses on a lineage of American Realism begun, in part, by Edwin Dickinson (1891-1978), a student and contemporary of Charles Hawthorne (1872-1930), through the present day. Though representing various genres, themes, and approaches, these artists share a commonality which involves painting from direct observation. This exhibition celebrates a representational lineage that has persevered through the antagonism of the Modern era and continues to enrich the discussion of contemporary American art.

Artists:

Charles W. Hawthorne (1872-1930) Susan Jane Walp (b. 1948)

Gwen John (1876-1939) Tim Kennedy (b. 1954)

Edwin Dickinson (1891-1978) Charles Ritchie (b. 1954)

Fairfield Porter (1907-1975) Eve Mansdorf (b. 1955)

Arnold Newman (1918-2006) Scott Noel (b. 1955)

George Nick (b. 1927) Philip Geiger (b. 1956)

Lennart Anderson (b. 1928) James Fitzsimmons (b. 1957)

Gregory Gillespie (1936-2000) Neil Riley (b. 1957)

Gillian Pederson-Krag (b. 1938) Tim Lowly (b. 1958)

Rackstraw Downes (b. 1939) Gideon Bok (b. 1966)

Stanley Lewis (b. 1941) Elizabeth Geiger (b. 1967)

Mark Karnes (b. 1948) Sangram Majumdar (b. 1976)

St John’s College

The Mitchell Gallery

60 College Avenue

Annapolis, MD 21401

Gallery open noon to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday and from 6:45 to 7:45 p.m. on Friday before the College lecture or concert. Closed on Monday.

I’ll give a lecture about the exhibition on February 17th at 5:30pm and there will be a panel discussion with some of the artists on February 22nd at 3pm. All are welcome to attend!

MORE

January 28th, 2015 by dave dorsey

This studio of mine is humming with work right now, which is why it’s been so long since I’ve posted anything. I have a backlog of about a dozen posts I want to write, including a long conversation I had with Jim Mott recently, as well as an assortment of random thoughts, some long overdue praise for a long-gone Thiebaud exhibit I saw at Aquavella, and hopefully something about the fine new show of quasi-Tonalist contemporary work at Oxford Gallery right now, if I can pull away from painting long enough to focus on this blog. I’m almost done with work for my two-person show in March at Oxford, but still have plenty left to do–slowly and steadily–which generates a bit of anxiety as time grows short and the work proceeds at its own insistently careful pace. I’m loving the work though.

I’m also going to do a series of posts in reaction to my impulse purchase of The Birth of Tragedy, through the Kindle app on my tablet. I’ve been devouring it over the past few days. It’s an incredible book, very short and dense with original thought, and it’s hard to believe it’s so early in Nietzsche’s career, his first published work. The thinking is so subtle and complex, and the compression of his thinking reads like something from late in a philosopher’s career. In it, he questioned the role of science long before it became clear that technology could actually replace human beings, as it appears ready to do, and he went back to Greek tragedy to find a creative focus around which he could cluster glancing insights into art, philosophy and religion–in opposition to the notions of progress and rationality that arose with Socrates. I was softened up for a rereading of something by this German thinker after listening to so many podcasts from Entitled Opinions (whose host regularly revisits Heidegger’s interrogation of Western civilization, a project he inherited directly from Nietzsche, whose name also comes up regularly with guests on that Stanford University program.)

Now that I’ve reread this book, I think Nietzsche might actually have disapproved of the sort of painting I do, and that itself might be worth a post, because I would have something contra Nietzsche to say on the matter, but he’s making me examine the assumptions underlying what I do. Very little of what’s so powerful in this book relates much to the notions for which Nietzsche eventually came to be known: the ubermensch, eternal recurrence, and so on. He returns again and again to the effect of music in classic Greek tragedy: how it unveils an entire world and an obliteration of the self in a kind of cosmic sorrow and wonder that employs the events and characters of the drama as a shield through which that sorrow can be experienced as joy. His thinking strikes me as insightful when it comes to how the cleverness and conceptualism of art in the past century has broken it free of its moorings. The loss of a central mooring is what he was lamenting already, just as modernism was coming to life–without being able to express directly what the crucial impetus of creative work was. So much to write, so little time . . . but I’ll be able to get back to posting soon.

January 18th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Chaucer, as new as he ever was

I was browsing through the squibs in the front of the most recent The New Yorker fresh from my mailbox, hoping to find something to see on a quick trip to Manhattan where Nancy and I, along with a couple friends, have tickets for the Matisse show at MoMA. I spotted three things that stood out, not for what they were critiquing, but for the thoughts expressed in these A.D.D.-friendly five-sentence reviews. Here they are:

1. Museum of Modern Art: “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in the Forever Now.”

“The ruling insight that the thoughtful curator Laura Hoptman proposes and the artists confirm is that anything attempted in painting now can’t help but be a do-over of something from the past, unless it’s so nugatory that nobody before thought to bother with it.”

(But my first response to this was: I will see your nugatory and raise you a negatory. Yes, history has run its course for visual art. The notion of progress is dead. But I have some humble qualifications that fly in the face of what I this show’s apparent tone and spirit. More below.)

I turned the page and found my counterpoint already put into words:

2. Marcus Roberts

While raising money on Kickstarter for his latest project–recording a suite of music that he wrote some twenty years ago, called “Romance, Swing, and the Blues”–the pianist and composer declared that “all great jazz is modern jazz–whatever the age of the piece, we make it ‘modern’ (relevant to our own time in history) when we play it.” This multi-stylistic dictum informs his work with his new twelve-member band, Modern Jazz Generation, which recently released a double album of the material.

(Obviously, right? The individual performer makes it new. Anyone who has heard a great cover knows this.)

3. “The Contract”

In the European Union, artists receive a royalty each time their works are resold. The U.S. has no such droit de suite, but in 1971 the curator-dealer Seith Siegelaub drafted a rarely used contract to guarantee artists fifteen percent of profits from future sales. The conceit of this show is that all the works in it . . . are subject to the agreement. Is this premise better suited to an article or a symposium than it is to an exhibition? Probably, but in this turbo-charged art market the show has the rare virtue of subordinating speculators’ profits to artists’ welfare. (The show, at Essex Street, was over on Jan. 11, even though this issue of The New Yorker is dated Jan. 12. Which is typical of these notices in The New Yorker: some seem to sit in the queue until after their use-by date.)

Last things first. I wish I’d seen this show just to have been in a place briefly MORE

January 16th, 2015 by dave dorsey

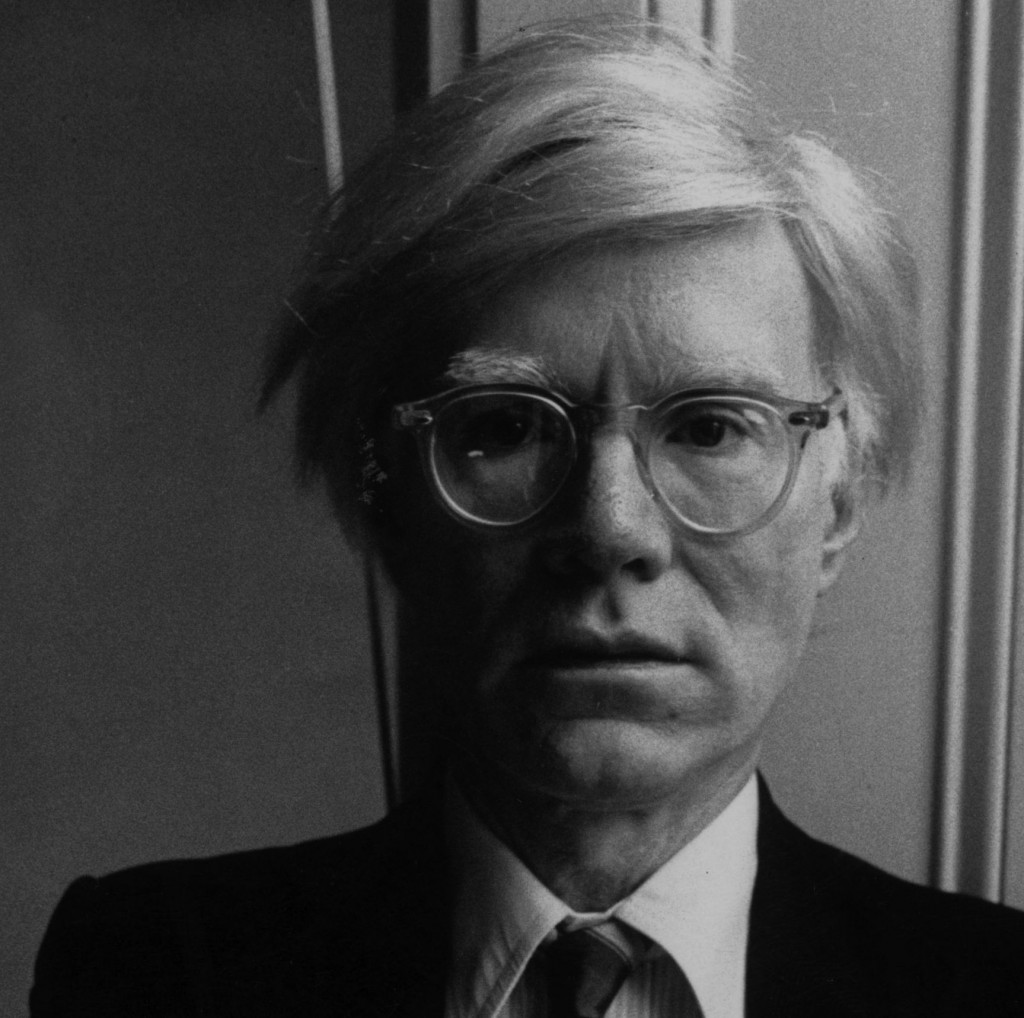

(Photo by John Minihan/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

From Kevin Pollack Show, #223:

Joel Murray: Back in the day, we were out one night, with Gilda Radner and my mother . . .

Kevin Pollak: We?

Joel Murray: My brother Brian and Bill. I wanna say this is the same night we saw Robin Williams at the Copacabana early in the evening with Lucy Arnez. Saw Robin do a show that blew us away. This is 1979, 1980. I laughed my ass off and I sat next to this strange guy who did not laugh once. White-haired fellow. I was like, who is the dead wood? Oh, that’s Andy Warhol. (Beat) Did not find the show funny.

Speaking of Warhol, even after he had become a major celebrity, I read this morning that Warhol more or less kept his day job, doing magazine illustration as late as 1986. That old Pittsburg work ethic dies hard. Plus, it was as much a work of art as anything else he did.

January 14th, 2015 by dave dorsey

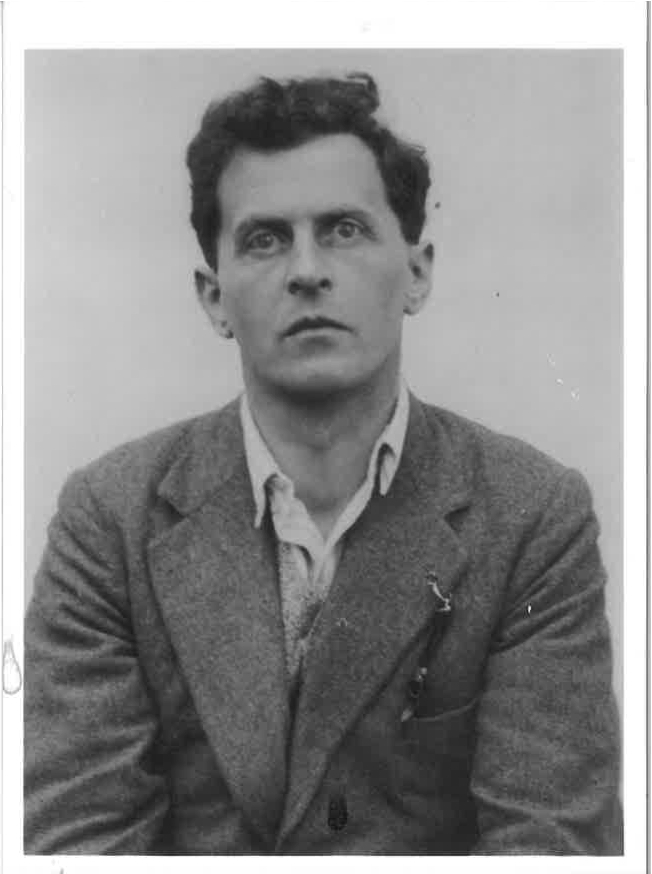

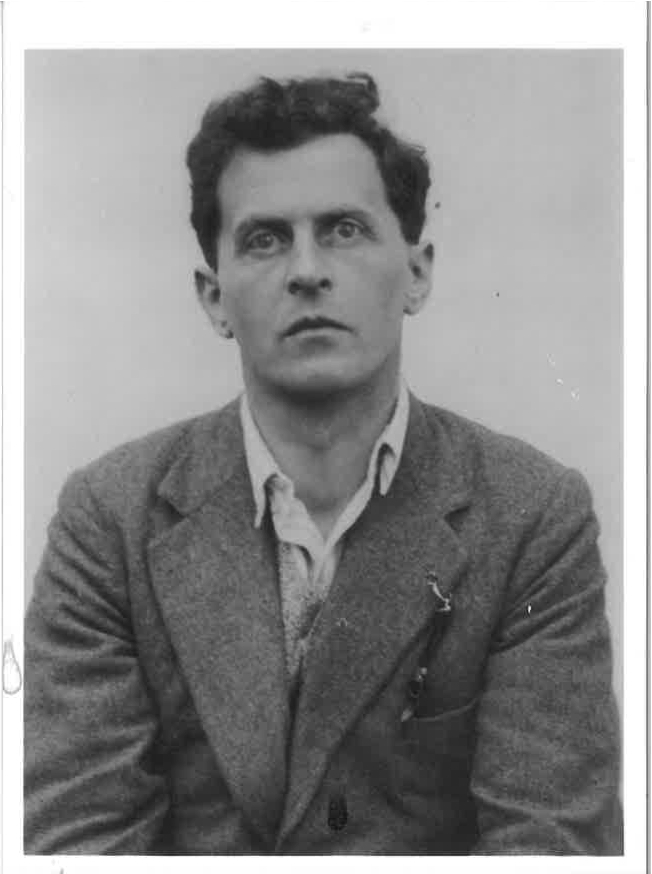

Ludwig Wittgenstein

A shot from a small piece where poets pick their favorite photographs in the Paris Review. (Speaking of which, I read a few days ago that George Plimpton was at Bobby Kennedy’s side when the candidate was shot. Did Plimpton ever do anything boring aside from brushing his teeth? I’m assuming he did it the way the rest of us do.) Ann Lauterbach, on this picture of Wittgeinstein:

The Wittgenstein photograph is unsettling; it’s as if he can barely see out from his mind’s fervent activity. There’s something eerie about looking back at him, into his uncomfortable, intelligent eyes, and thinking about the silence that every photograph compels us to acknowledge. I think about this silence often, and the indifference of images to it, and the ways in which captions try, but ultimately fail, to undermine it. Wittgenstein thought a lot about the relationship of silence to words . . .

As did Heidegger. Images as far more akin than writing (and thinking) to the silence Wittgenstein pondered. Poetry gets closer to it than any other form of writing. “Indifference” puzzles me: “The indifference of images to this silence.”

January 12th, 2015 by dave dorsey

It’s gonna need some windows.

Will Harlem become the new Bushwick? “We should be cultivating affordable housing in general.” http://bit.ly/1zZny6R

January 10th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Jim Mott’s oil of a dog walker he saw in Arizona

I could write a dozen posts based on my conversation this week with Jim Mott. Knowing me, I probably will eventually, one way or another, but one small point we talked about just surfaced while I was working on something entirely unrelated to painting. We both spoke about work habits and how difficult it can be to paint on a fixed schedule. He has intense resistance before sitting down to paint. He’s told me in the past that he approaches every new painting feeling as if he has to learn all over again how to make a picture, though he knows a wealth of things about how to paint. As painful as it is, he thrives on this sense of flailing at the start, struggling to simply get a grip on what he’s going to do, mark by mark–the instability of that moment seems necessary for getting a purchase on what has to be done each time he sits down to paint. My habits are much different. I have a set of methods that enable me to ignore those uncertainties, up to a point, and they make the earlier stages of building a painting almost routine–with the exception of the first stage, seeing the image I want to paint. That’s when I feel exactly as Jim does. Discovering that image is really the first moment of anxiety and struggle for me. Since I work with photographs I’ve taken, I can spend half a day or most of a day, just trying to compose and capture a picture that will end up as the source for a painting. Jim faces the same uncertainty when he wanders through a landscape looking for what he’s going to paint–and he had a funny story about how, on one of his peregrinations, he used a GPS coordinate generator to find utterly random scenes, and how he forced himself to paint even the most unappetizing views of the region, based on the locations his software calculated. He forced himself to stick with the locations without, as it were, rolling the dice again.

Normally, for me, finding a picture just means working within the slightest variations of light and setting around my own home, involving a few objects I’ve painted before. It’s amazing how difficult this can be, because I need to have some kind of emotional response to what I’m seeing; there has to be something enticing about recreating it in paint, and that’s not easy to inspire, even if I’m simply setting up a still life in an artificial way. It’s never a sure thing. I can even come up with a shot that I believe is exactly what I need but when I begin to paint it, I realize it won’t come together properly, and I abandon the painting. Also, I can lose what felt like a compelling image in the middle of painting it, which is when the struggle returns. There’s a point in almost every painting where I start doing things I don’t know how to do–problems I haven’t had to solve before. I discard far more paintings than I would like, but that moment of deciding that a painting doesn’t work–and it can be even after the painting is finished–is close to the mysterious crux at the heart of what painting is. A painting has to live, which is different from saying a representational image needs to resemble life itself. A painting can be an exact replica of what’s in front of the lens, either an eye’s or a camera’s, but that doesn’t mean it will come alive for a viewer. It needs to do more than simply look real; it needs to feel alive, both as a scene, and as a physical object on a wall. That comes, in my view, from the difficult delight of laboring, with an appetite for the work, hours and days and weeks or months, making a thousand marks, and another thousand, with a sense of wanting the paint itself to convey its own vitality, in addition to the way it persuades the eye that it isn’t simply looking at paint. To be that invested in something as fundamental and physical and mostly subservient as the act of painting is what’s required for the final work to strike others as vital and arresting. But what that life is, the quality of both presence and absence a good painting has, as people themselves do, the way it discloses and offers so much while also giving the sense of withholding just as much, and leaving so much out, unarticulated–there doesn’t seem to be any way of objectifying how this happens, or even describing it. The routines only take me so far, and then I’m as adrift as Jim before he starts working, from start to finish. The best indication that it’s coming together though, is nothing more authoritative than a feeling (which sounds nebulous but isn’t), a sense of anticipation and a willingness to keep working on a particularly tough section until it’s right, a surrender to the terms of what’s beginning to appear as you realize the unique challenge the work represents. Keeping that hunger alive, the appetite to keep applying paint, even when something resists everything you already know how to do, is what eventually makes the painting work. It’s something an individual achieves alone, and can’t be taught, though it’s easy to see its results in all the great paintings of the past. Seeing it in previous paintings is how I realized I wanted to paint in my teens.

January 8th, 2015 by dave dorsey

January 6th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I spent a couple hours talking with Jim Mott yesterday, which I’ll write about shortly, but I wanted to pass along this nice opening paragraph from the September New York Review of Books he gave me:

“Imagine the Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art as the perfect storm. And at the center of the perfect storm there is a perfect vacuum. The storm is everything going on around Jeff Koons: the multimillion-dollar auction prices, the blue chip dealers, the hyperbolic claims of the critics, the adulation and the controversy and the public that quite naturally wants to know what all the fuss is about. The vacuum is the work itself, displayed on five of the six floors of the Whitney, a succession of pop culture trophies so emotionally dead that museumgoers appear a little dazed as they dutifully take out their iPhones and produce their selfies.

Of course even those who take a serious interest in Koons know that he’s also full of baloney. Roberta Smith, reviewing the Whitney retrospective in the Times, comments on his “slightly nonsensical Koonspeak that casts him as the truest believer in a cult of his own invention.” That is well put. The essential fact about the Koons cult, however, is not that Koons invented it, but that it has gained such extraordinary traction, in the art world and well beyond. Day after day, the crowds are lining up outside the Whitney, waiting to get in to see the Jeff Koons show. What are they to make of the tens of millions of dollars that have been squandered on this work? What are they to make of the critics and historians who are defending Koons with a belligerence that allows for no debate? And what are they to make of the Whitney Museum of American Art?

That Koons will be Koons is his own business. That he has had his way with the art world is everybody’s business. No wonder the people in the galleries at the Whitney look a little dazed. The Koons cult has triumphed. For his next project Koons should consider manufacturing a ten-foot-high polychromed aluminum Kool-Aid container.

Jed Perl, New York Review of Books