Archive for October, 2015

October 31st, 2015 by dave dorsey

We’ve had a couple killing frosts already here, which is typical: snowfall by Halloween. And then it’s followed by a string of much warmer, Indian summer days, a temperate mix of sun and clouds, sometimes for weeks. One thing about Western New York, at least in my suburb, is that robins sing only into June, and then we hardly see them until the next spring. I have no idea where they go or why they don’t keep plucking worms from the grass all summer long. They retreat to more wooded areas or maybe properties where the birdbaths get cleaned more often than ours does. Or they just don’t like me. That’s probably it.

We’ve had a couple killing frosts already here, which is typical: snowfall by Halloween. And then it’s followed by a string of much warmer, Indian summer days, a temperate mix of sun and clouds, sometimes for weeks. One thing about Western New York, at least in my suburb, is that robins sing only into June, and then we hardly see them until the next spring. I have no idea where they go or why they don’t keep plucking worms from the grass all summer long. They retreat to more wooded areas or maybe properties where the birdbaths get cleaned more often than ours does. Or they just don’t like me. That’s probably it.

It makes me feel a little cheated. Every time I visit my cousin Brian in Laurel, Maryland, near Baltimore, I hear flocks of robins singing up and down his street, regardless of what month it is. I want to shout up into the branches, hey what gives? Yet, as the sun came out this morning, robins showed up again, way ahead of schedule, and started fighting for exclusive claim to the birdbath, and then half a dozen of them were hopping around in the front yard, tilting their heads to the side. Then, while I was sitting in my studio I heard one of them singing in a crabapple next door. This is something of an event around here for me—which may be sad commentary on my particular suburban life. A little more birdsong and, let’s be honest, three more blowout backyard parties per year—which would be three more than I usually have—and I’d be a pretty happy camper. Maybe the robin was announcing that winter isn’t coming after all, and we’ll finally get a local windfall from global warming. As I understand it, we’re one of two places on the globe where temperatures have been declining steadily as they rise everywhere else on the planet.

Whatever inspired him to sing, I’ve decided to take that little avian tune as a good omen for breaking old patterns. Recently, I resolved to shift my painting more resolutely toward a new method I’ve followed off and on for years, but without MORE

October 28th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Yellow Labyrinth, Anthony Dungan, acrylic on canvas

The new show, “The Elusive Image”, at Oxford makes an amazing impression when you walk into the gallery. As I wrote before, it’s one of the most unified exhibitions I’ve ever seen there, all abstract, or at least semi-abstract, modernist work. Part of what gives the show such immediate impact is the seriousness of the intent on the part of all three artists: Bill Santelli, Anthony Dungan, and Jan Hewitt Towsley. It’s all modernist in the sense that you’ll find no hints of postmodern irony about the nature of the work itself—or the suppositions behind it. It varies between quasi-representational and almost entirely abstract, with Dungan’s powerful new nudes as the most figurative.

Towsley’s constructions, work that is woven from filaments of metal, look perfect in the company of the paintings around it, but it gets a little overshadowed. It’s quiet, glowing, subtle and, at times, intricate without being overly complicated. My favorite is a rippling curtain of metal screen that flows in waves down toward the floor, like a Chinese scroll with figure-eight curves that seem permanently pressed into the fabric. Up close, a variety of colors emerge, and, as does all of her work, it reflects light differently from different angles (something it has in common with the gold leaf areas in some of Bill Santelli’s drawings). Jim Hall, in his write-up for this show, does the best possible job of describing the strength of Towsley’s work:

A weaver may appear an odd choice to exhibit with two painters, but the compositions of Jan Hewitt Towsley more closely approximate, at times, that of a painter or draughtsman than that of a traditional weaver. Although she does weave patterns in more conventional materials, such as cotton, silk, or linen, many of Hewitt Towsley’s compositions are woven of metallic ‘thread’. Such work would have to command our admiration if only for its sheer difficulty of execution. But we might say that this artist “draws” with her loom, creating still-life compositions, landscapes, and cityscapes. The images seem to exist in a space somewhere between two and three dimensions. They announce themselves with the play of light not only upon different metals, such as brass, copper, or steel, but upon weaves of different type and density. The images are chimerical, as they emerge, change, and disappear when we move around them.

I’ve already delved into Santelli’s work in an interview posted a few days ago. It breaks down into four categories, three of them familiar to me in addition to a small series of minimalist geometric abstracts based on the dimensions of a tennis court seen from above. I’ve admired his work over the years, but in the context of the show, it came alive in a new way for me, though I’m not sure why. This time, MORE

October 25th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Hawaii Dream Flash 13 (detail), Bill Santelli, acrylic on canvas

The new show at Oxford Gallery, “The Elusive Image,” makes a powerful impression when you walk through the door. The gallery has integrated the work of all three artists–Bill Santelli, Tony Dungan, and Jan Hewitt Towsley–into a show where everything you see augments the work around it. The tension between angular, hard edges and organic curves ripples from one work to the next, leading your eye forward and back to reassess things you’ve already seen. It’s probably the most unified show I’ve seen at Oxford, and the work is all first rate. I’ll write more soon to share impressions about Dungan and Towsley, but for now I’ll pass along some of the conversation I had with Bill as he walked me through the show, commenting on the work.

Bill’s work falls into three buckets, more or less: large abstracts that set up a tension between geometric shapes and eddies of paint that form partly through chance; his PATH abstractions that call to mind tall grass in the wind; and his “silent dialogs.” He also added a small set of drawings, minimalist squares in the dimensions of tennis courts seen from directly above. We started with the little Open Court series and moved to The Path drawings and then the larger abstracts:

When I was working on (the Open Court series), I was thinking they’ve already been done as large paintings.

I really like them on this scale. The size adds to the sense of restraint and minimalism.

I think I’ll keep the series going for a little while to see how they turn out.

You can see your hand in them, despite how flat and spare they are. There’s real feeling in the tiny variations of color in each grid. They’re so close to watercolor.

It’s funny you say that because I was thinking of doing these in watercolor. Then at the last second—I was even thinking of thinning out acrylic—but with the work on The Path drawings and Zen Mind/Silent Dialogue stuff going in Prismacolor, I figured I’d do the first one in Prismacolor and I got hooked on it.

How does Prismacolor work? What’s different about it?

It has a fair amount of waxy content to it.

It’s in pencil form?

Yes, you can get them in stick too. But those are chalkier.

It sounds similar to pastel.

Yes. They aren’t forgiving in terms of erasability. I’ve tried scaping with a blade but you can’t get all of it.

Do you have something to guide your hand?

No, the series started with just making a mark spontaneously. What I really was doing in the beginning was just putting down the color without the black (outlines) and for whatever reason I kept looking at it and thinking this isn’t really popping the way I wanted it to. So I outlined one mark in black and really liked it and then just went ahead and did it all.

I don’t know how you get such a steady line.

They aren’t one continuous line. I go a ways and stop. Then again. Tom Insalaco gave me the hint to use a bridge. I started using a bridge above the paper. Sometimes I use tracing paper or plastic sheet so I can put my hand or arm on it while I’m putting down the mark. They are smaller strokes, but I try to get into the motion (of the whole line). You can see all the little strokes, if you catch the light just right. The inspiration for these was sea grass. My father in law had a house on the north fork of Long Island where we used to go in the summers. We could take a canoe out and just go out. There were always the grasses. The whole series, I started when I’d ordered some pre-stretched canvas and had nothing to do, so I had this paper lying around and going through file drawers looking for something I found this box of paper. I just got it out and made a slashing mark and liked it to much that I kept it going.

You did it spontaneously. A large quick gesture?

A swift mark like the beginning of one of these only bigger.

The first one could be fast, but after that . . .

Exactly.

There are so many parallel lines, perfectly aligned.

After the first one, I recognized something and was thinking about it, and my wife came in and said, that looks like the grasses. I started looking at them more and just kind of went from there.

When I first saw these I moved on, but the more I see them the more I like them. I see more and more in them. There’s a Taoist feel of the grass surrendering to the force that moves it. They are so simple, I thought, OK, I’ve figured that out, nothing much to see here, and I’ll move on. But there’s more and more there.

You can see there’s a lot of build up of layer. It isn’t that it’s applied thickly initially. It’s all these tedious strokes to get the color I want. These drawings take about three months on average.

That’s astounding to me. The other thing that fooled me at first, it looks like a print. I thought they were “just” lithographs. But these are one-off. To spend that amount of time on something that is, in the end, this simple . . .

I didn’t paint for almost a year. When I first put these out there, they were getting a fair amount of attention, so I went with it and kept it going. It took so long to do one of these, and I was working eight hours a day and had no energy left.

You have very clearly defined areas of flat color.

The black outlines really makes it work.

Frank Stella did white margins that worked the same way.

Yes. That’s it. They are a challenging. It gets to be like meditation.

(We move on to the large abstracts.)

How do you get the paint to behave this way, with these eddies and swirls? It has a life of its own that you seem to guide and nurture without too much forcing.

I did a lot of research on paint when I started working seriously and I was reading all the literature about Golden acrylics. I also studied Paul Jenkins and Frankenthaler and others and learned they were working in oil and Chrysochrome, (an enamel). Jenkins was the most scientific about it. I worked for Zora’s Art Supplies at the time and went to Zora to ask what Chrysachrome was – and she admonished me: “Look it up in the dictionary! Learn for yourself!” That was what started my studying and experimenting with mediums and different paints.

Swimming inside a David Hockney could be a bucket list item for the serious collector.

People paid him to paint their actual swimming pools. So I was asking what’s chrysachrome? With these it’s basically, first mixing the viscosity and getting it to the point where it isn’t too thick or too thin. I’ll lay it down, using hake brushes, so that it has texture but not brushstrokes. The first layer I’d take the hake brush and dip it into whatever medium I was using and put that down and then add color. With the hake brush you can manipulate it.

The shapes and patterns look natural, as if they form on their own.

The color in the rectangular shafts are things I remember from dreams. (Jim called these armatures and that’s a great description.) (In the organic areas of free-flowing paint) sometimes the paint has the consistency of milk and if it gets too thick it’s harder to control when you put down the second or third or fourth layer. The Renaissance painters used to work on copper and they wanted the light to come back from underneath. I want the light to work that way as well, so the layers have to be of a certain viscosity.

In this one you can see sky, and that’s what’s interesting, it’s like a view of interior states but you can see external worlds in these images too.

October 24th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I’m passing along the latest email from aeqai, an online arts magazine in Cincinnati. I’m an occasional exhibitor in Ohio thanks to Manifest and the Butler Institute, so I’m also one of their readers. If you think the only way to see great art is to live on one of the coasts, just take a glance at what’s going on in Ohio (aeqai is reaching out to other places as well–thanks to its correspondents). It’s impressive:

The month of October always brings with it not only glorious weather, but some of the most fascinating art shows tend to appear during this month every year, and 2015 is no exception. Exhibition offerings are very strong, and the October issue of aeqai, now posted, is full of reviews, profiles, and manifests aeqai’s growth into new cities: we introduce Elisa Mader, who’ll be covering the visual arts in Seattle for us, this month, as well as Joelle Jamison, who will be covering Houston for us, regularly, joining Anise Stevens, our LA correspondent, and Cynthia Kukla, who has Chicago as her beat. And next month, we’ll be introducing area photographer Kent Krugh, who has become aeqai’s photography editor, and will be selecting photographers’ work from the region, nationally, and internationally and offering our readers photo essays of the work he selects for us.

Both the art museum and the Taft Museum have singular offerings : Keith Banner reviews the Jacob Lawrence painting show, recently opened at The Taft Museum in a strong and passionate review of Lawrence’s work from the thirties, while Jonathan Kamholtz analyzes the one Raphael painting that’s traveling the world right now (which we think’s a terrific idea). Two reviews of recent Contemporary Arts Shows/performances aren’t in yet at press time, but we will post them when they come.

Matthew Metzger returns this month as an aeqai critic, and he went to Antioch College to review a show about the rhyzome, a complex metaphysical idea that the Antioch Curator has adapted into an art show with the most splendid of results, with the assistance of a professor of sculpture there: this is a must see show, and it’s a great time of year to take this short drive to this lovely town so close to us, in Yellow Springs. Zack Hatfield offers a thoughtful anaylsis of photographer Elena Dorfman’s work at The Weston Gallery in The Aronoff Center; aeqai reviewed her work several years ago, and her career seems to be soaring. And Craig Ledoux, who started with aeqai last month, both reviews and offers an overview of the public art/mural scene in Covington, including an interview with both Jay and Cate Becker of the BLDG (building) , who’ve been so responsible for this burgeoning scene in Covington, which is celebrating its 200th anniversary this year (The Carnegie also offers several shows dealing with Covington’s birthday /anniversary, which is why we asked Ledoux to write this column now).

Hannah Leow reviews an oddly moving show of work by Jane Carver at The Art Academy of Cincinnati; our review of The Michael Lowe Collection of (conceptual) photography will appear next month rather than this month due to extenuating technical problems on the writer’s now old computer. Fran Watson, whose knowledge of prints and how they’re made always amazes us, reviews Frank Hermann’s new monoprints on offer at Clay Street Press, and new aeqai writer Dan Burr takes a look at a small group show at the Women’s Y downtown, called “Color” and featuring work by, amongst others, Paula Wiggins and Susan Mahan. Burr, whom we welcome to aeqai this month, will be reviewing for us regularly, too. And Marlene Steele reviews Cedric Michael Cox’s new work at The Clifton Cultural Arts Center: Cox’s work’s optimism is always refreshing to see in such a dystopian era. And Jennifer Perusek, aeqai’s fashion editor/correspondent, looks at the Alexander McQueen line of women’s clothes this month, after the truly tragic and untimely death of visionary McQueen himself.

Aeqai offers two profiles this month, both of area artists: Mike Rutledge’s profile of Brad Austin Smith, one of our region’s most creative and prolific photographers, who has a new photo in the upcoming Mapplethorpe After 25 Years show at The CAC, opening in November, and Laura Hobson offers a profile of regional draughtsman and painter Marlene Steele, who also writes for aeqai regularly. Marlene Steele also offers a fascinating review/essay on The Letterheads, a group which met here recently and deals with all kinds of aspects of signage, graphics and the like , as well as older design forms including calligraphy, at which Steele herself excels. We hope that you’ll read Steele’s piece as it’s truly fascinating, and most of us know little about these fields.

Aeqai has a slew of reviews from other cities. Our own Jane Durrell was visiting Atlanta, and found a museum at Emory Univeristy which is full of ethnic memorabilia and objects from cultures around the world, but reviews the temporary show there about Native American arts and culture; it’s a fascinating review and there’s much to learn from it. Our LA writer, Anise Stevens, offers two reviews, one of a show of work by African-American geometric abstractionist–all 46 of them–in a show that’s an eye opener. Her other review of new work by NY artist Randy Hage, shows us work in the realistic , almost photo-realistic vein, of storefronts, current and those long gone, in New York, and they’re miniaturist as well as dimensional, too: this show sold out at its opening in LA. The work is sensational, as is her review of it. Our Chicago correspondent, Cynthia Kukla, looks at Charles Ray’s sculptures of mainly male nudes at The Art Institute, and she doesn’t much like the macho bombast which she describes and anaylzes so admirably. Elisa Mader, of Seattle, reviews work by Lisaann Cohn, in a show that shows influences from Surrealism, Egon Schiele and others, that looks fresh and exciting and beautifully rendered. And Joelle Jamison looks at a design show at Houston’s version of our Contemporary Arts Center: Houston has a very active design scene in clothing, furniture, jewelery , and the like: much fascinating art’s coming out of Houston; next month she’ll write about the Houston photography scene.

Louis Z. Bickett of Lexington returns with another of his fascinating photo-essays, this one called “Sam with Broom: South”; these photos are part of a large, ongoing series of deadpan/conceptual photographs where a young man named Sam wanders the Lexington area and throughout the South with one broom. And I offer two book reviews this month, of phenomenal new short stories by Ann Beattie, a truly rare treat, and of a very disappointing new novel by very talented writer Lauren Groff.

We’re also posting with this eblast an invitation to the aeqai benefit party, to be held on Tuesday, November l0, at The Weston Gallery in the Aronoff: tickets are cheap at $40/head, and we’ll have a great art auction, thanks to the vast generosity of regional artists: we hope you’ll come; everything’s tax deductible as Aeqai is a 501c3 nonprofit. Nibbles and wine/beer’ll be on offer, and this event’s aeqai’s major fundraising event, and we hope you’ll come and support it, and if you can’t, please consider sending a tax deductible check anyway.

We’ll return in a month –November’s issue will include a lot of material on the FotoFocus sponsored symposium on Mapplethorpe/lessons learned , which’ll take place on the 23rd and 24th of October at The CAC (their show opens a couple of weeks later). New York FotoFocus Curator Kevin Moore has put together one of the most impressive groups of experts and specialists worldwide for this event, and we encourage you to attend various parts of the symposium as you can. It’s a major event in and for Cincinnati, and aeqai will review the symposium and the show next month.

Daniel Brown, Editor

October 22nd, 2015 by dave dorsey

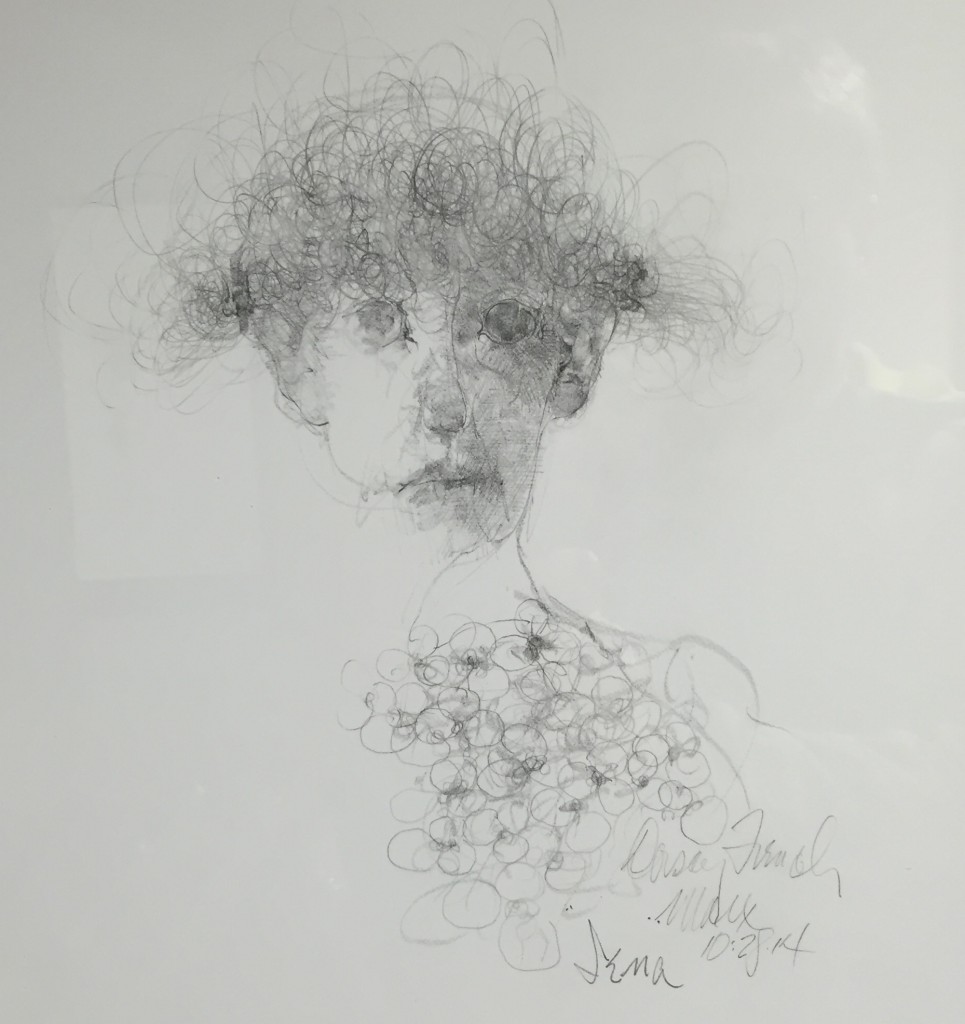

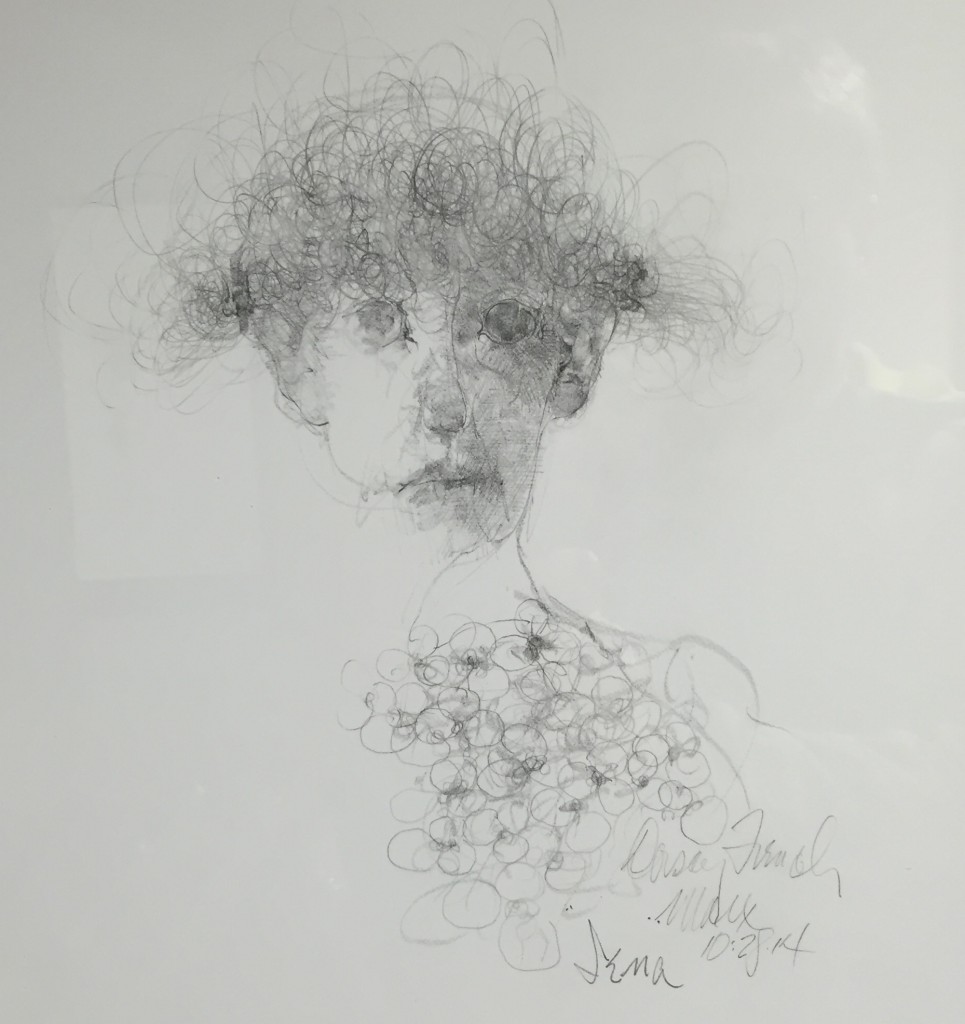

Iena, Robert Ernst Marx

I have to say Robert Ernst Marx, now 90, is still at the height of his powers, based on a recent visit to his current one-man show at Rochester Picture Framing. It sounded like an unlikely venue for such an esteemed local artist. Yet it’s a beautiful, perfectly-lit space, and Marx appeared to have sold around $20,000 worth of work already. So it appears to be a perfect fit. His vision is as it has always been: dark, full of spectral inquisitors and aristocratic succubi who seem half-Elizabethan, half-Gothic. His world reminds me of Goya’s black period when the Spaniard painted Saturn feasting on his son and Titans going after one another with cudgels in the dusk. Marx, too, paints the monsters generated by the sleep of reason–he’s as skeptical and unforgiving as a French philosophe. His figures emanate menace with nothing more than a steady gaze. In his minimalist portraits of spiritual deformity he invests all the complexity into the way he applies the paint while indicating as little as possible about his imaginary sitter. His color is surprisingly rich and subtle. In his drawings the line is masterful and utterly free and in the example above, occasionally lovely. That’s in his wheelhouse too.

October 19th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Nancy, Danville, Virginia, 1969

The day I graduated with my master’s degree in photography, my mother told me, we’re so happy you became a photographer. I looked at her, stunned, because I knew that her intention and my father’s had been for me to follow him [in the ministry]. I have exactly his name; I was to be the stereoscopic repetition of my father. So I stared at my mother, and finally she said, ‘Oh, we were so afraid you might become an artist!”–Emmet Gowin, from “Hidden Likeness”

1

When I came away from the Morgan Library’s recent retrospective of Emmet Gowin’s photography, I was stunned at how he was able to make his vision both personal and universal. In the last twenty years of his career, the personal element nearly disappears as he almost completely loses himself in loving attention to the world of insects. The smallest details in Gowin’s images often carry a lot of weight, and yet there’s very little detail in his work that anchors it to a particular era or even a particular place. His family photographs from half a century ago could have been shot decades earlier as a contrarian vision of idyllic bliss in Depression-era Appalachia—or in any number of other rural places. His aerial glimpses of catastrophes or environmental blight or nuclear testing sites remind me of shots relayed back from Pluto or Mars, or maybe fragments of inconclusive clues from one of Fox Mulder’s X-files. The truth is out there, but you won’t know what you’re looking for until you’ve shot it and brought it home. His wonderfully humble photographic catalogs of moths and butterflies in South America could be taxonomies from an entomology textbook, or a sequence of pictograms from a lost language. They are powerful in part because he is a lone explorer finding and honoring such tiny, obscure moments of nature’s inexhaustible beauty. The longer he has worked, the more universal his images look, and yet you can feel his idiosyncratic passion in every image.

It’s a wonder how much mystery and enigma he manages to convey, subliminally, MORE

October 14th, 2015 by dave dorsey

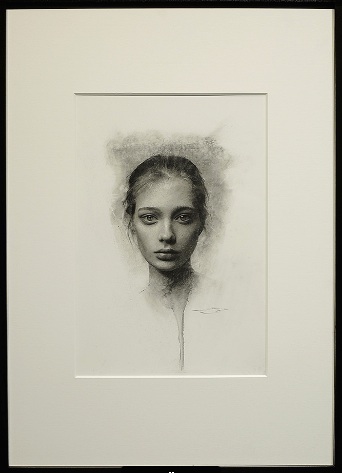

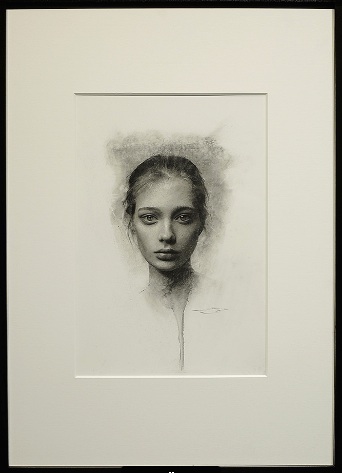

“Youth”, Casey Baugh, charcoal on paper, 16″ x 11″, Arcadia Gallery.

“Youth”, Casey Baugh, charcoal on paper, 16″ x 11″, Arcadia Gallery.

October 10th, 2015 by dave dorsey

In the New York Times book review this Sunday, Jonathan Franzen used a term familiar to me only from Martin Heidegger’s writings on technology. As result I got curious to know how Thomas Sheehan’s recent book about the German thinker has been received. I didn’t come across any reviews with a Google search, but I did find a paper he’d written last year, “What, After All, Was Heidegger About?”, which serves almost as an overview of the new book, which I haven’t finished. The paper is far easier to understand than the book simply because it’s less laden with un-transliterated Greek words (there are still plenty) and the footnotes are easy to delete and ignore if you copy and paste the content into Word. How’s that for a workaround to avoid distractions? (My apologies to Sheehan’s assiduous attributions demonstrating the depth of his comprehensive scholarship on the German philosopher.)

I’ve read the paper a couple times and may post a reaction to it. I’m no authority on philosophy, but I still read it as part of an effort to cobble together, slowly and haltingly, a view of what painting has the potential to do, when it is at its best. Heidegger’s thinking represents a personal cornerstone in this effort, based on what little he wrote about visual art–though Sheehan’s essay doesn’t address the philosopher’s views in a way that helps me much with that right now. Still, it’s lucid and brief and apparently controversial among some core Heideggerians. But this is what I gather second-hand, because I don’t “follow” philosophy. I’m a layman dogged by philosophic questions, and I have only few un-entitled opinions to air about it.

Which brings me to the good news. Entitled Opinions, where I discovered Sheehan, is back! I’m only two podcasts behind in the new season. The Stanford University radio program had been gone for more than a year. I can’t wait to hear Robert Harrison’s new discussions as they become available. I can hear echoes, in the paper, of things said in conversation with Harrison, about how Heidegger did little to address the subject of ethics as a philosopher (and made some questionable ethical/political choices as an individual). But mostly the content of the paper is distinct from much of what Sheehan has said about Heidegger on this podcast. I hope he’s on deck, or at least somewhere in the season’s line-up, to talk at length about his new paradigm for understanding the philosopher.

October 8th, 2015 by dave dorsey

This made me laugh, as was intended, maybe because Renoir is my least-favorite Impressionist. BBC coverage of an anti-Renoir demonstration:

The Boston Globe reported that they chanted: “Put some fingers on those hands! Give us work by Paul Gauguin!” and “Other art is worth your while! Renoir paints a steaming pile!”

October 1st, 2015 by dave dorsey

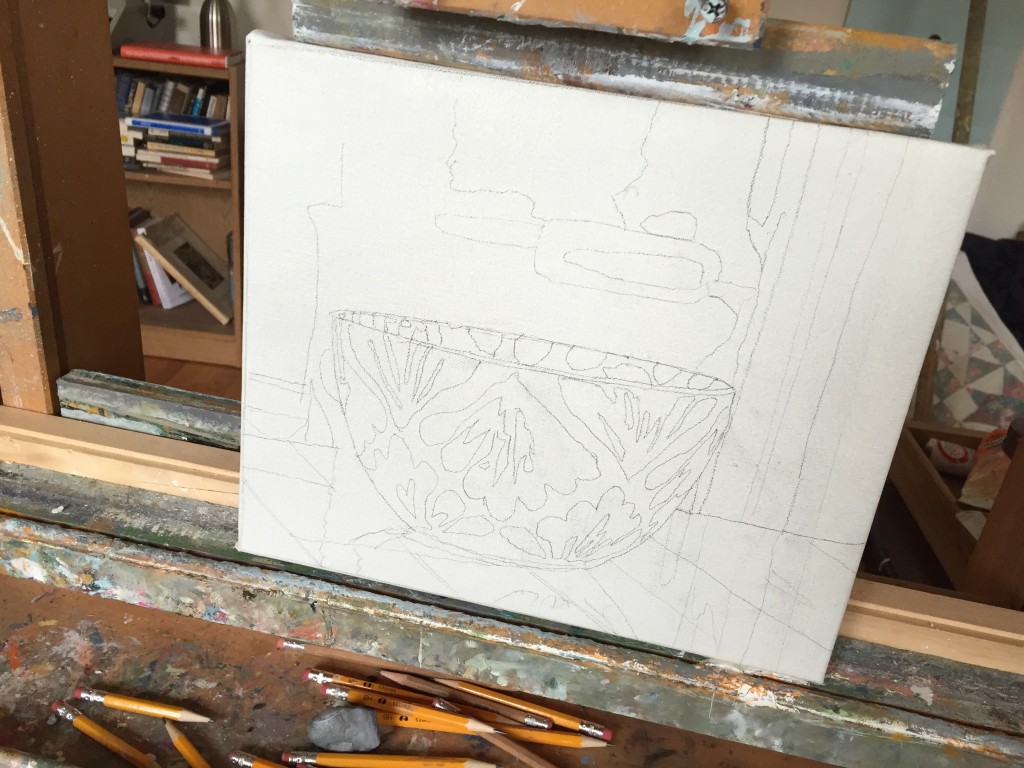

Gifts, oil on linen, 53 x 53

1

Starting this spring, and all through the summer, I’ve worked on only one painting. I’ve never invested this many calories into a single painting, this much obedience to the act of looking at a particular set of objects. I suppose this can’t be an entirely good thing for a person, but I’m pleased with the results. For me, painting is rhythmic, like factory work—you do a certain amount each day, on a regular basis, and at the end of X number of days you have a painting. This one has been different. Most days, since early May, I’ve put in several hours of writing every morning, first thing, usually from 6 a.m. to 9 a.m., which enables me to pay the bills, then another four to six hours of painting, seven days per week. I took much of July off, in the middle of all this, when I went sort of rogue, insofar as that’s possible at my age, and I rode 1,700 miles around New England and into Canada on my eleven-year-old BMW R11050R motorcycle, mostly staying with friends. Then I came home and got back to painting, wielding my brush with the wrist I’d made sore during a couple weeks of using it to twist a throttle. Around four each day I would settle into a chair for a while or go for a run. Writing this blog took a backseat, as did most other things. My absorption with this painting drew me away from a number of other activities, and last week I more or less finished it. I say that provisionally, since no painting is ever finished until you store it somewhere you won’t see it again, preferably in the home of a new owner–or send it off for exhibition. I’ve already entered in in a show at Manifest, so that means it’s done.

This newest painting is an overhead views of a tabletop’s corner, with wedges of Persian carpet beneath, and various household objects strewn at random over the white tablecloth, some like tropical birds perched on snow. I’ve been doing these tabletops for twenty years, probably finishing a dozen of them in all, and I think I secretly hope this one will be the last. I undertook it partly as an effort to complete a definitive version of this personal genre.

I started doing these tables in the 80s after a long obsession with Braque. MORE

We’ve had a couple killing frosts already here, which is typical: snowfall by Halloween. And then it’s followed by a string of much warmer, Indian summer days, a temperate mix of sun and clouds, sometimes for weeks. One thing about Western New York, at least in my suburb, is that robins sing only into June, and then we hardly see them until the next spring. I have no idea where they go or why they don’t keep plucking worms from the grass all summer long. They retreat to more wooded areas or maybe properties where the birdbaths get cleaned more often than ours does. Or they just don’t like me. That’s probably it.

We’ve had a couple killing frosts already here, which is typical: snowfall by Halloween. And then it’s followed by a string of much warmer, Indian summer days, a temperate mix of sun and clouds, sometimes for weeks. One thing about Western New York, at least in my suburb, is that robins sing only into June, and then we hardly see them until the next spring. I have no idea where they go or why they don’t keep plucking worms from the grass all summer long. They retreat to more wooded areas or maybe properties where the birdbaths get cleaned more often than ours does. Or they just don’t like me. That’s probably it.