November 21st, 2019 by dave dorsey

The Light in The Room, detail, oil on linen.

My most recently finished still life makes me uneasy. If I look at it in a dim light, before going to bed, I’m gratified that I did almost exactly what I set out to do—capture a glowingly illuminated kitchen in the middle of a bright, summer day. But during the daylight hours, if the surface of this painting is well-lit, I want to crawl into a corner and close my eyes.

I had this same feeling a year ago last month when I went to see my prominently displayed paintings—I could see them through the front windows of the museum while parking my car on the street—at the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art exhibition in Wisconsin, jurored by Frank Bernarducci. Once I got up close, by virtue of the unsparing gallery lighting, the brushwork made my skin crawl. I felt exposed. The execution didn’t appear to have bothered anyone else, considering the placement of the two paintings. But ever since that opening, I’ve been concentrating on the thickness of the paint—endeavoring to get a Goldilocks feel, not too thick, not too thin—and the way I need to handle it, wet on wet. I’ve been conscious of the desire to user thicker paint for years, but this determination to paint wet into wet began when I returned from Wisconsin last year. (I make exceptions when this isn’t possible, when I see something in the already dried coat that makes my stomach tighten with disappointment, as it did yesterday with the taffy painting I’m doing now. But I make my amendments by putting down uniform areas of wet color and then going back to push detail into them immediately.)

I don’t want what I’m rendering to look hyper-realistic. The paint should look like paint, not the surface of a photograph. But it needs to flow gradually from one spot to the next. No rough edges where edges don’t form clear lines and borders in the source. So now, today, the formerly irksome part of the painting doesn’t make me want to hide when I look at it. It’s all about the nature of the brushwork, the energy and visibility of the mark (or just the way the paint flows from one tone into another) as catalyst for how the eye flows across the image and reads it. I don’t expect my brushwork to be what it is in Van Gogh, or Sargent, or Manet, or Hals, or Thiebaud, or Jenny Saville. But the brushwork now doesn’t get in the way of what pleasure I get from looking at what I’ve done. It isn’t at odds with the image. But when I see areas where the paint is applied skillfully in terms of value and hue, but it just looks awkwardly scumbled, dragged across already-dry paint, and the edges of each spot of color make it look scuffed and chaotic, then I want to slip the painting away into storage. I don’t, because it’s a decent enough painting. Yet his knowledge doesn’t help, which I take as a good thing. Excellence requires striving.

It’s all about whether or not the eye bumps into a spot of paint or glides over it, riding the energy of the paint itself, the life it imparts to the act of looking. I am probably right in reacting this way to the work I’ve done. But maybe not. When it comes to painting, it’s best not to be certain of anything except in those rare cases when I know the painting is really finished and as good as I can make it. (I’m certain about the prefection of most of Vermeer, and quite a bit of Piero, but that’s a pretty safe certainty and though I know I’m looking at a painting when they’re the ones making it, the marks they make aren’t all that visible.) The less refined execution might end up being what people value most in some of these paintings I want to avoid seeing—the way in which the surface is at odds with the image it induces you to see. In fact, I’m constantly trying to do smaller, more improvisational paintings that are all about the visibility of the paint and where the areas of paint look abstract and unrecognizable up close—in other words, simplified and much more painterly work. But this isn’t what I’m after in the sort of paintings I’ve been exhibiting over the past decade—with the exception of one small interior with figures, quickly executed with easy brushwork, I showed at a pop-up in London years ago.

The humorous element here is that with either kind of brushwork, my current painting looks roughly the same from a few feet away—and the magic of Chardin resides in how, up close, it is just a chaotic mess, while a little farther away, it’s amazing. But it’s a good chaotic mess up close. His paint was thicker, more sensuously applied, more like Thiebaud than Vermeer, so that the paint itself was a pleasure to see. As opposed to what I’m dealing with. But I’m working on it.

November 18th, 2019 by dave dorsey

The Window, Matisse, oil on canvas, 57″ x 46″

One of the treasures from my visit to the Detroit Institute for Arts Museum, and displayed near two equally excellent paintings. Historically speaking, it’s only a short walk from this painting (hanging with two equally beautiful pieces by Matisse) to the work of Richard Diebenkorn. Yet this was painted half a century before Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series. What’s baffling is how so much lyrical feeling can be invested in such a restrained and limited range of colors.

November 14th, 2019 by dave dorsey

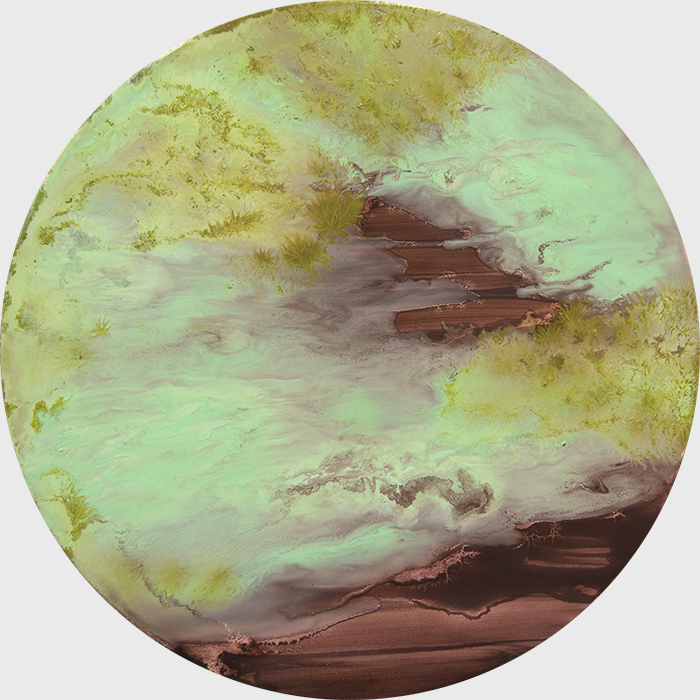

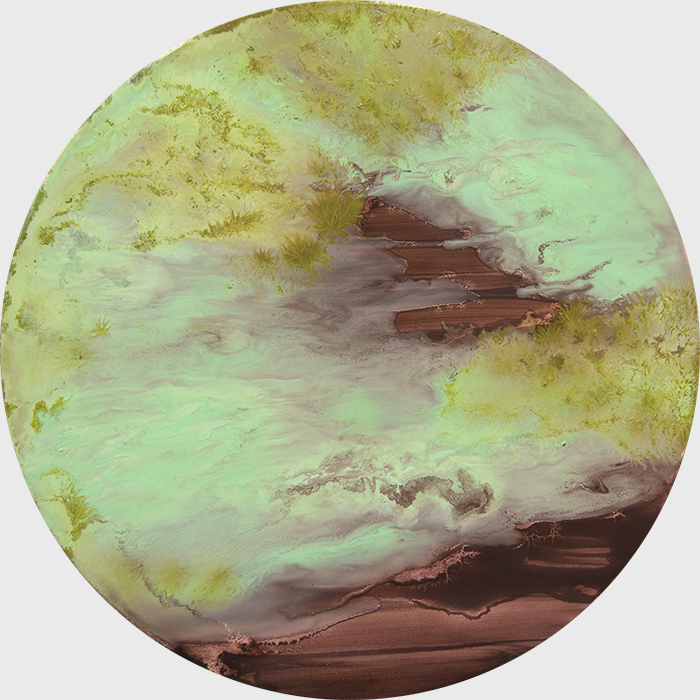

Moment #34, H.K. Freeman, oil on panel, 18″ diameter

I collect spoors, molds and fugus.

—Egon Spengler

In the fungus among us, H.K. Freeman sees a world suffused with seemingly chaotic but purposeful mystery. That alone marks her as someone worthy of attention. Fascination with things almost everyone else ignores or shuns, for me, is a springboard for originality in visual art. She is yet another interesting artist I discovered in Manifest’s recent Painted exhibit. Freeman’s current obsession reminds me of Emmett Gowin’s full immersion in the South American rain forest, devoting himself to capturing moths, not with a net but with his photographic lens. Yet moths are already beautiful. Anyone who has come across a cecropia moth, as I once did in our back yard many years ago when we lived in Utica, will not be able to look away, the wings are so Blakean in their eerie glamour. With fungus, not so much. Noting the mold on my basement cinder blocks after a rainy month, I reach for the bleach.

But Freeman is a spiritual cosmologist. She sees wonder and mystery in what others recognize only as decay. She marvels at a devouring life form that is neither animal nor vegetable, but something that eats the world’s leftovers as an after-after-party clean-up crew. In all fairness, anyone who has enjoyed a portobello or truffle knows that fungus can taste pretty good, as well. Freeman shows us something more rarefied in her sometimes tiny spherical paintings of fungus that look like miniature worlds viewed through a microscope, or the surface of planets light years away.

But Freeman is a spiritual cosmologist. She sees wonder and mystery in what others recognize only as decay. She marvels at a devouring life form that is neither animal nor vegetable, but something that eats the world’s leftovers as an after-after-party clean-up crew. In all fairness, anyone who has enjoyed a portobello or truffle knows that fungus can taste pretty good, as well. Freeman shows us something more rarefied in her sometimes tiny spherical paintings of fungus that look like miniature worlds viewed through a microscope, or the surface of planets light years away.

She’s at her best when she finds a symbiotic strength in her medium’s proclivities, offering a little guidance here and there—like a color field painter pouring and steering a flow of paint. It’s both a practical and a symbolic relationship with materials. Anyone who has worked in the natural world, say, growing a garden, recognizes the partnership. The garden does most of the work. Anyone who has tried to steer himself or herself through the world recognizes how free will represents a tiny marginal allowance you earn through prior discipline, simply for the chance to choose against the daily inertia of one’s character. You are there to nudge things—including yourself—this way and that, toward the desired end. When she finds the effects she wants by letting the paint do what it does on its own, but  intervening where needed, the work is enchanting.

intervening where needed, the work is enchanting.

What’s marvelous is that, in this fascination with one of the lowliest of life forms, she sees God. She doesn’t preach, just passes along her awe at how much order and beauty and shines forth from the world of decomposition. She’s working a field Richard Wilbur tilled in his great poem about the vulture, and how that carrion bird’s meals serve the same purpose as an ark, delivering life from death.

From Freeman’s website:

The intricate worlds of lichens, fungi, and mosses serve as a starting point for my paintings. These sublime organisms help ensure and maintain life on earth. I draw upon the history of landscape painting and abstraction, together with eco-theology, to communicate spiritual ideas in relation to creation. Using the finite to think about the infinite, the paintings evoke the mysterious, wondrous, interconnected process of existence.

I alternately manipulate the paint and playfully relinquish control to create these worlds. The imagery simultaneously fuses and dissolves, oscillating between certainty and uncertainty with the promise of resolving into something familiar. The luminosity of the colors and the use of abstraction convey the euphoric, transcendental sensation of my initial encounter with the subject matter. The abstraction and the colors stimulate not only the visual senses, but also act on the psyche to contemplate the painted microcosms. I hope the references to creation will invite viewers in, while the abstraction will challenge viewers to perceive in a way that goes beyond the surface of the painting, so they can explore their own thoughts and beliefs.

November 11th, 2019 by dave dorsey

Ed Clark, Maple Red, Oil and mixed media on canvas, 73″ x 76″

I discovered this magnificent painting at the Detroit Institute of Arts Museum on a visit late last month to Detroit. I recognized the artist when I saw it from a distance only because I’d recently discovered him after news of his death. I felt like Art Brut singing about their ignorance about The Replacements: “How have I only just found out about Ed Clark?”

But Freeman is a spiritual cosmologist. She sees wonder and mystery in what others recognize only as decay. She marvels at a devouring life form that is neither animal nor vegetable, but something that eats the world’s leftovers as an after-after-party clean-up crew. In all fairness, anyone who has enjoyed a portobello or truffle knows that fungus can taste pretty good, as well. Freeman shows us something more rarefied in her sometimes tiny spherical paintings of fungus that look like miniature worlds viewed through a microscope, or the surface of planets light years away.

But Freeman is a spiritual cosmologist. She sees wonder and mystery in what others recognize only as decay. She marvels at a devouring life form that is neither animal nor vegetable, but something that eats the world’s leftovers as an after-after-party clean-up crew. In all fairness, anyone who has enjoyed a portobello or truffle knows that fungus can taste pretty good, as well. Freeman shows us something more rarefied in her sometimes tiny spherical paintings of fungus that look like miniature worlds viewed through a microscope, or the surface of planets light years away.  intervening where needed, the work is enchanting.

intervening where needed, the work is enchanting.