Mitchell Johnson

Mitchell Johnson, Luxembourg, 2022, 16×16

the painting life

I came across this opening to one of Philip Larkin’s essays at random when I spotted the collection on a shelf. He’s admiring John Betjeman for the limpid quality of his poems, their immediacy and accessibility, like the polymath conversational style of early W.H. Auden and James Merrill in The Changing Light at Sandover, a style that conveys an eagerness to be understood and a friendly sense of accessible humanity. He contrasts this kind of simple clarity with the work of T.S. Eliot, though Eliot’s The Journey of the Magi represents exactly the sort of poem Larkin loves:

The scene is worthy of a nineteenth-century narrative painter: The Infant Betjeman Offers His Verses to the Young Eliot. For, leaving aside their respective poetic statures, it was Eliot who gave the modernist poetic movement its charter in the sentence, “Poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult.” And it was Betieman who, forty years later, was to bypass the whole light industry of exegesis that had grown up round his fatal phrase, and prove, like Kipling and Housman before him, that a direct relation with the reading public could be established by anyone prepared to be moving and memorable.

It strikes me as a passage that perfectly describes what I like in the work of most painters I love: the immediate sense of being shown something fresh and recognizable at some level, like a melody that instantly starts replaying itself in your brain. Creations that work without the need of interpretation, as Susan Sontag celebrated, because in the way they are painted, the artist conveys qualities equivalent to those conveyed by an individual’s facial expressions, body language, bearing, way of speaking . . . in other words the entirety of a single human wholeness expressed in all the little parts. But the quote also points back to a time when painting didn’t require an instruction manual or a critic to do its work. That time is still now for most painters I love.

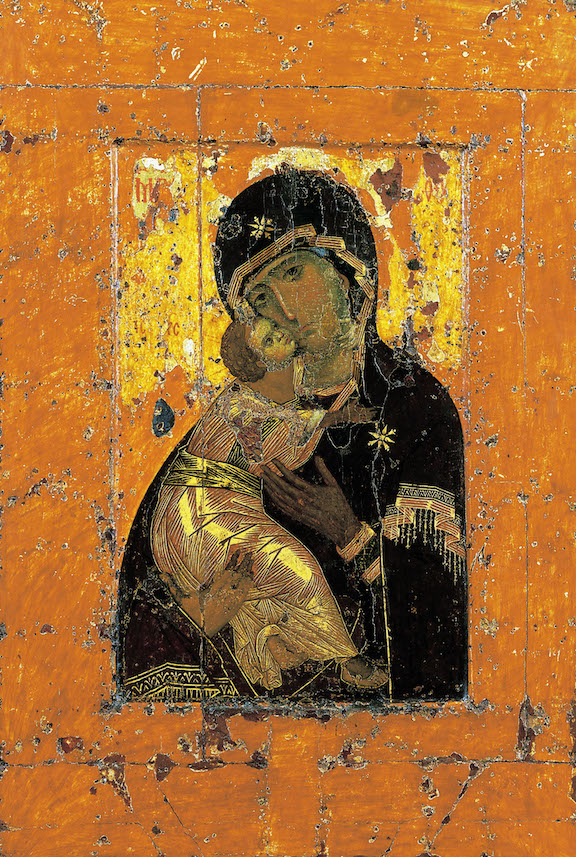

Theotokos of Vladimir, 11-12th century Constantinople, egg tempera, 27 x 41

From the Old Jordanville Prayer Book:

Rejoice, height inaccessible to human thought.

Rejoice, dawn of the mystic day.

Rejoice, rock that refreshes those thirsting for life.

Rejoice, door of solemn mystery.

Rejoice, thou who shows philosophers to be fools.

Rejoice, thou who exposes the learned as irrational.

Rejoice, ray of the noetic Sun.

Rejoice, thou through whom creation is renewed.

–Excerpts from the Akathist to the Theotokos

These lines, in an oblique way, express–in a more ecstatic mode–how I’ve responded to much visual art since my teens. It’s hard to imagine how something in this spirit could be sung as an accompaniment to paintings being made now. Where are the mysterious painters who might evoke this sort of mystical affirmation? Some modernists would have recognized something like this as the mission for painting, Klee and Chagall, even Kandinsky, and many others. Some of the modernist writers as well, Proust and Flaubert (if you look at the arc of his subject matter over his career) and Eliot and Auden.

The Old Jordanville Prayer Book is named after a Russian Orthodox monastery south of Utica, New York, a place I visited in the 80s, a period when I was studying print-making at Munson-Williams-Proctor and writing for the Utica newspapers. When we lived in Utica, I saw a retrospective of Charles Burchfield paintings at the museum that had a deep effect on me, as well as a survey of contemporary representational art that opened up my sense of the possibilities available to me as a painter. When I was assigned a feature story on the Jordanville monastery, the spiritual energy I discovered there astonished me. What most impressed me was how the monks were busy publishing literature to be smuggled into the Soviet Union, before it fell apart, when that country was most repressive, harassing and persecuting its own Orthodox practitioners. Russia maintained tight censorship over religious publications, so the role of producing and distributing books, as samizdat, that Christians wanted within Russia’s borders, fell to a little organization in upstate New York, Holy Trinity Monastery. My visit there bolstered my interest in and respect for Russian Orthodoxy which began in college when I read J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey and then The Way of the Pilgrim, probably the best-known book associated with this church. Now, years later, after having read Everyday Saints–stories about monks in the Soviet Union when the regime was actively hostile to their faith–I found Russian Orthodox services only miles from where I live, in Brighton, NY, at the Protection of the Mother of God. It’s a beautiful place to try and quietly contemplate the ultimate reality of life with people more meek and humble than I am, while being surrounded by paintings on nearly every square inch of wall and ceiling, which seems a particularly appropriate haven for a visual artist to keep an eye on his own spiritual health. One of my good friends at the church, Father Theophan, a Danish monk from Holy Trinity, lives in Brighton–more or less on assignment from Jordanville to assist the church–paints icons, and is also translating the Psalms into Danish from Greek and original versions in other languages. His path began when he read The Way of the Pilgrim around the same age as when I read it–and he likewise became both a painter and writer. At some point, I hope to do a post about him. I’m fascinated by how icon painting is an ongoing and mostly overlooked niche of the art world, continuing without any expectation of economic reward or critical recognition.

I write this post in memory of Peter Shehldahl, The New Yorker’s art critic who confessed to being a non-church-going Christian when he knew he was terminally ill, not long before he died in October. His intelligence and humanity lives on in his writing.

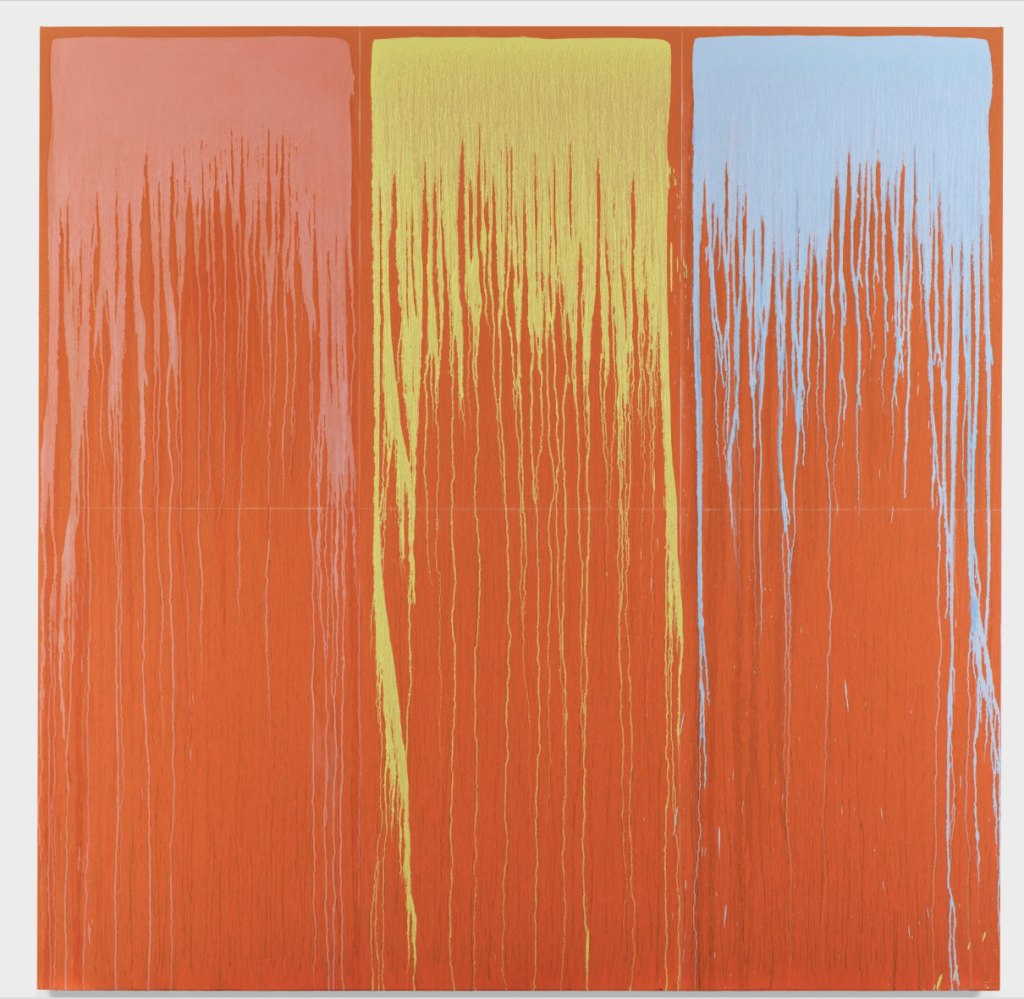

Pat Steir. Rainbow Waterfall #5.oil on canvas, 108 x 108

Get to Hauser and Wirth in the next day or two, your last chance to get a glimpse of Pat Steir’s powerfully simplified and radiantly colorful drip paintings, including the largest canvas she’s ever done. She reduces her methods to the most uniform imagery, from painting to painting–working slight variations in color and scale, with an almost Warholesque sense of choosing color schemes within the repetitive armature of an almost identical shape. Chalk lines form a faint grid against which the random journey of the drips sink downward. More to the point, these paintings do what the great color field mimimalists did, severely simplifying the means of making an image and then finding limitless prospects for wildly different states of consciousness as you move from one immersive field of color to the next. The resplendent paintings hum with life. There’s a great review of the show at Hyperallergic.

Get to Hauser and Wirth in the next day or two, your last chance to get a glimpse of Pat Steir’s powerfully simplified and radiantly colorful drip paintings, including the largest canvas she’s ever done. She reduces her methods to the most uniform imagery, from painting to painting–working slight variations in color and scale, with an almost Warholesque sense of choosing color schemes within the repetitive armature of an almost identical shape. Chalk lines form a faint grid against which the random journey of the drips sink downward. More to the point, these paintings do what the great color field mimimalists did, severely simplifying the means of making an image and then finding limitless prospects for wildly different states of consciousness as you move from one immersive field of color to the next. The resplendent paintings hum with life. There’s a great review of the show at Hyperallergic.

Summer Fruit, Yuval Yosifov, oil on canvas

Only a few days left around the holidays to see this painting (properly stretched and framed in the show) along with work by other painters who studied in Israel in Shapes of Light at the Figure/Ground Gallery in Seattle, a spiritual sister to Sugarlift in Chelsea, where Zoey Frank’s recent work is on view until Jan. 7. Yosifov is young and gifted, someone to watch.

The beauty of her abstractions are Rebecca Purdum’s greatest appeal, bringing to mind both late Monet and Color Field. Yet what delights me the most about her website is the plain-spoken, no-nonsense artist’s statement which is admirably titled: “A few words”:

To start a painting, I look at a surface of infinite possibility. How to find the one image that will be this painting? How to paint something I’ve never seen before? Even after making hundreds of paintings, it is still possible. That anticipation, and its affirmation when a painting is finished, is why I paint abstractly.

Whether a painting is nine feet or sixteen inches, they begin the same way. During the process of painting, however, many factors influence what happens next. Early on, it’s one-sided with my decisions propelling the action. As the surface grows, a shift occurs so that what I want is no longer important. The painting dictates what it needs. I know the painting is finished when what I see has a physical and emotional resonance, unique in time and place. That’s why all the paintings are different.

By contrast, I offer a sample from www.artybollocks.com, the random AI artist statement generator. First results upon clicking the words “generate some bollocks”:

My work explores the relationship between the universality of myth and recycling culture. With influences as diverse as Rousseau and Francis Bacon, new insights are distilled from both mundane and transcendant meanings.

Ever since I was a pre-adolescent I have been fascinated by the essential unreality of the zeitgeist. What starts out as hope soon becomes manipulated into a carnival of defeat, leaving only a sense of nihilism and the unlikelihood of a new synthesis.

As temporal forms become frozen through studious and critical practice, the viewer is left with a clue to the possibilities of our era.

Love that last sentence. At the bottom was a link asking “still not good enough?” Who could resist? I clicked up this:

My work explores the relationship between the Military-Industrial Complex and copycat violence. With influences as diverse as Caravaggio and Joan Mitchell, new insights are created from both orderly and random layers.

Ever since I was a child I have been fascinated by the theoretical limits of relationships. What starts out as yearning soon becomes corroded into a carnival of futility, leaving only a sense of what could have been and the chance of a new order.

As shifting forms become transformed through emergent and critical practice, the viewer is left with a clue to the limits of our world.

With influences as diverse as Monty Python and Woody Allen, the bollocks generator does a nice job of impersonating the average statement, but this carnival of pretention can’t compete with the way Purdum just sticks to the craft and doesn’t try to say what can only be shown. As someone once put it: “What can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence.”

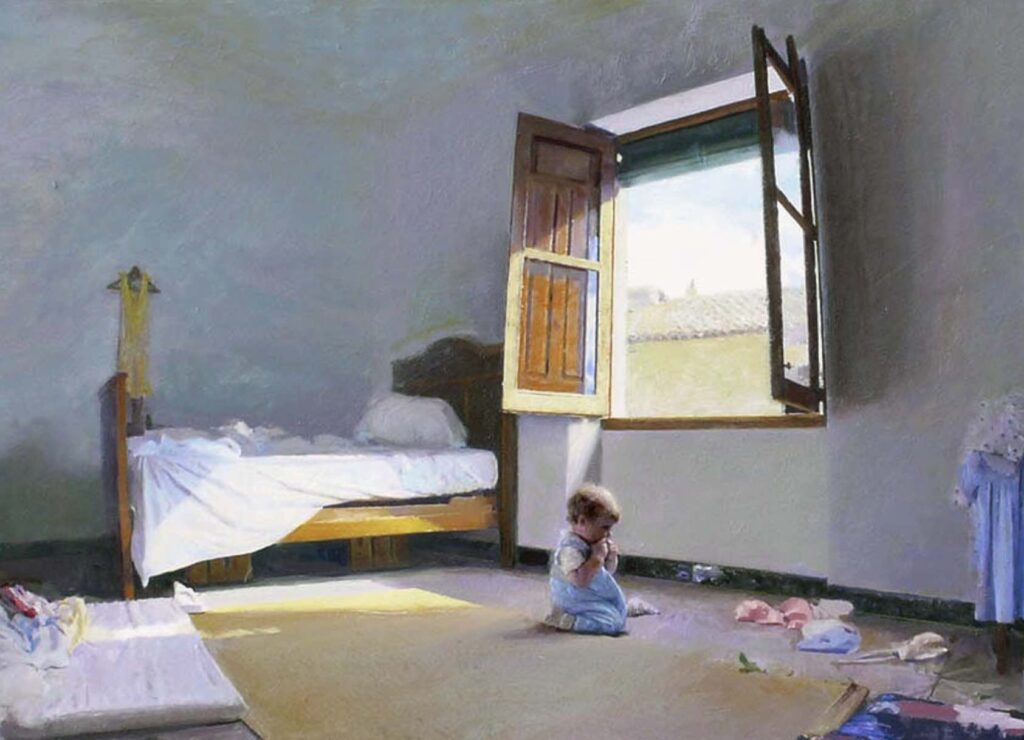

He goes by a single name, like Madonna or Bono or Sting, the contemporary Spanish master, Golucho, completely self-taught and mostly under-the-radar if you try to learn more about him on-line. One finds little written about him, but he’s considered part of the New Realism, with Antonia Lopez Garcia in the forefront of the movement. His work is less astringent that Garcia’s, more willing to use unnatural tones of color to evoke a response that moves the viewer beyond one’s initial amazement over his boldly persuasive technique. It’s easier to think of Garcia as a photo-realist, though Golucho likely is working at least partly from photographs of his subjects. His use of color varies from restrained to lush, from beautiful to assertive, and his drawings of aged bodies seem to descend from the Northern Renaissance yet don’t look coldly clinical. Occasionally he emerges from his information embargo to teach briefly and then withdraw: once at the New York Academy of Art in 2009 and then with a group of Chinese students who came to Spain in 2017 for a week of instruction hosted by the International Arts and Culture Group based in Florence, Italy.

His figures and still lifes are frequently lit from overhead, and both are startlingly vivid with brushwork that seems to be almost Tonalist, layer upon layer over surfaces he scores and scratches. His mastery reminds me of Jerome Witkin but his brushwork is less bravura, and his compositions are simplified and often almost vacant except for a human figure and a few indications of a room with random furniture: figures that look as if they are on a stage in the middle of a Beckett play. His few translated comments are more profound than most artist statements. In one he sounds like Hemingway on the art of writing: “The best part of painting is what hasn’t been painted.” One could take that enigmatic pronouncement a number of ways, syntactically: what’s left out as a result of the artist’s skill, what’s yet to be done by future painters, what remains to be done to a given painting but is yet to appear. A longer comment aims at the heart of painting, the quality no amount of art criticism can pin down or reliably identify:

His figures and still lifes are frequently lit from overhead, and both are startlingly vivid with brushwork that seems to be almost Tonalist, layer upon layer over surfaces he scores and scratches. His mastery reminds me of Jerome Witkin but his brushwork is less bravura, and his compositions are simplified and often almost vacant except for a human figure and a few indications of a room with random furniture: figures that look as if they are on a stage in the middle of a Beckett play. His few translated comments are more profound than most artist statements. In one he sounds like Hemingway on the art of writing: “The best part of painting is what hasn’t been painted.” One could take that enigmatic pronouncement a number of ways, syntactically: what’s left out as a result of the artist’s skill, what’s yet to be done by future painters, what remains to be done to a given painting but is yet to appear. A longer comment aims at the heart of painting, the quality no amount of art criticism can pin down or reliably identify:

The problem with realism is that everyone believes that they understand it, they think before a realistic picture that its aim is the mere representation of everyday life. On the other hand, abstraction makes the viewer become humble and say ‘I don’t understand it’ and in that way, by not discovering that picture, they’re closer to the testimony of that work, but when it comes to quickly ‘understanding’ the painting, there is realism. The conclusion is that the viewer stays on the surface of what is represented and this work can be left in mere appearance and in technical ability.

What he appears to mean is that critical attention can focus on nothing but appearance and technical skill. What many might understand from these words would be: it’s easier to understand what greets you visually with a realist painting, it’s recognizable and that’s a great part of the pleasure, but simply transcribing the look of things isn’t the point. Abstraction can be puzzling and therefore brings the viewer closer to the actual mystery of painting, the way appearances point toward something less visible (something that isn’t intellectual content). But privileging abstraction pushes aside what feels like easily understood realism as a lesser form of painting, mere copying. What he’s likely saying is that “understanding” isn’t the point. The point is to see what’s being shown through what’s depicted, and that remains mysterious but the actual aim of the painter. You behold something you can’t carry away as knowledge. It isn’t available to intellectual analysis or description. To engage with it, you have to keep looking.

This month in the New York Review of Books, Jed Perl wrote what’s almost a seminal essay on the way contemporary artists are finding their place in the spectrum that runs from pure abstraction to pure representation. For his argument, he reduces the spectrum to a polarity. He wants artists to pick a side and stick to it: be abstract or representational and work within the lines dictated by that choice. Instead, dogs and cats are living together, and he doesn’t like it. By lamenting the loss of the trench warfare between abstraction and realism, he aims at the central challenge for an individual painter now, but doesn’t quite articulate it. It’s a wonderfully thoughtful and well-written assessment that nearly nails the universal quandary painters face now—but he doesn’t quite enable the reader to see his target. He zeroes in on it and then veers away like a pilot who notices his runway is occupied at the last minute.

Anarchy is axiomatic now: anything goes, and everything is contemporary. A small part of what’s produced deserves celebration, as is true of most human endeavors. But anything is possible because everything is permitted. This is pretty much the open field painters face. They choose their own rules, with or without the attendant philosophical justification for one’s métier that Arthur Danto requires each artist to keep handy, like a holstered sidearm hanging from the easel. Perl yearns for the old faiths, the face-off between abstraction and realism that carried forward from early modernism through the 60s and into the 70s when the cheerful ironies of Pop Art and color field minimalism and then photorealism seemed to overshadow the intellectual angst that gave AbEx such gravitas and made New York City the center of the global art world. But then, poof, the antinomies withdrew, and we have the slow-motion free-for-all of individual invention, our current scene. Oh, the humanity.

It puts us in a place where snobbery still prevails, everyone is welcome to look down on anyone outside a particular zone of taste, and justify the sneer with commentary on what matters in painting. As if what matters can be put into words. Everything has splintered and the splinters keep splintering until we have Donald Kuspit’s advocacy of neo-Old Masters pursuing idiosyncratic visions, which screens out the enormous and wonderful fecundity of what’s going on everywhere. Anyone who tries to say what ought to be privileged in art criticism is missing what’s most vital and unpredictable in both art and life. The good stuff is always surprising. Critics make plans; God and artists laugh.

What runs counter to Perl’s vision is the much broader sense among many painters that they ought to do work that answers to the demands of both abstraction and representation. There’s a loose spiritual confederation of perceptual painters who want to fuse representation and abstraction in a way that makes much of their work appear to belong to a consistent, new school of painting. From where I sit, perceptual painting is a much broader category. It’s any painting that achieves what it sets out to do without intellectual baggage, without the homework, without any conceptual foundation or fixed rules whatsoever: what you see is where it’s at, not what you or even the painter thinks the painting is up to. The thinking lags behind, like a high school girl trying to make the word “fetch” happen in Mean Girls. MORE

Back Shore, Philip Malicoat, 16″ x 22″, oil on canvas.

Tom Insalaco told me earlier this year to check out Philip Malicoat. His close association with Edwin Dickinson emerges immediately in one glance at his work, in both modes that Dickinson employed: the large, dark and mysterious figures and interiors and the quickly executed, nearly abstract scenes Dickinson described as “first stroke”: premier coup. Back Shore is clearly an example of the latter. From the Provincetown Art Association and Museum:

Philip Cecil Malicoat was a child of farmers with little exposure to the arts, first in Oklahoma, then in Indiana, before coming to Provincetown in 1929 to study with Charles Hawthorne. Malicoat went on to build a life in Provincetown, meeting his wife, the artist Barbara Haven Brown, and together raising two children, Martha and Conrad, both of whom became accomplished artists. Malicoat was active in Provincetown arts community as a member of the Provincetown Art Association and Beachcomber’s Club, a teacher, a painter, and, in 1968, a co-founder of the Fine Arts Work Center.

This new painting, from earlier this year, has the amazing quality Jessica Brilli often achieves with her vintage cars. The forms are utterly flat and abstracted, a geometric puzzle, and yet her handling of values makes the trunk of the car jut into view. That effect is supported by the one area of analog gradation from dark to light on the wall of the garage behind the car. The colors viewed individually are flat and muted, almost dull–that blue sky looks lusterless in a disciplined way, but arrange them in relation to one another the way she has and what comes to life is the heat and light and expectant silence of a summer morning, just before a longed-for getaway. The canoe is a wonderful touch, also given a sense of three-dimensional depth with the smooth shift in values along its curve. The whole painting comes alive around those two red tail lights, like a pair of opossum’s eyes, their little U-shaped highlights underneath the crimson irises echoing the slim arch of shine over the rear window. The car looks sentient but fast asleep, eyes wide shut, waiting. The restraint of the subtle hues, and the combination of uncommon tones, the rigor of her reduction of everything to the simplest possible terms, everything works inexplicably to create the aura of an eerie moment both commonplace and alluringly mysterious, everything charged with somnolent but vigilant awareness.