Archive for March, 2023

March 24th, 2023 by dave dorsey

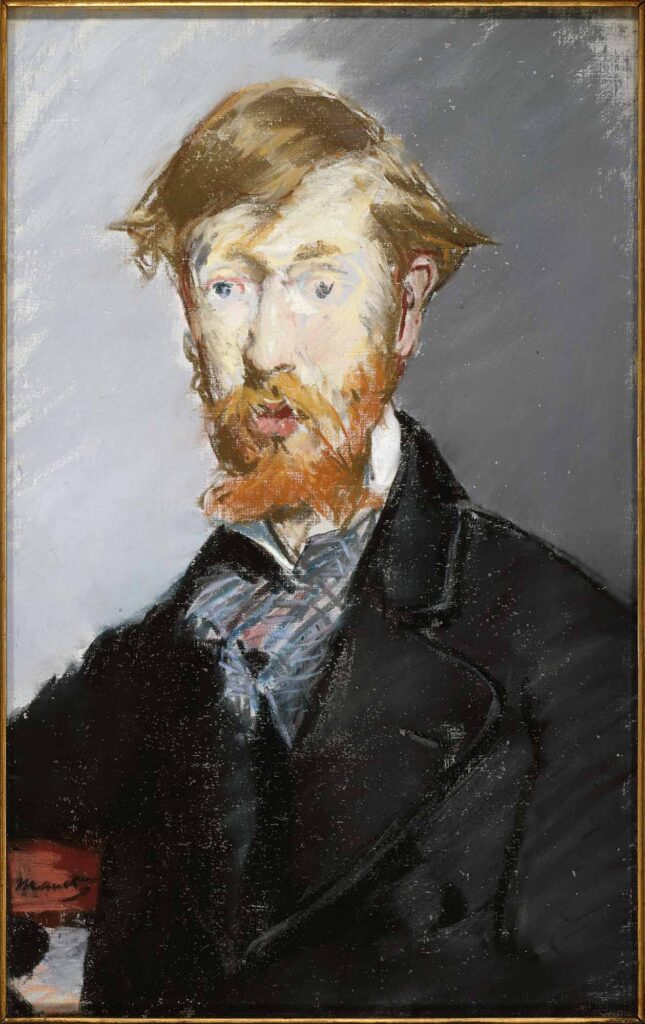

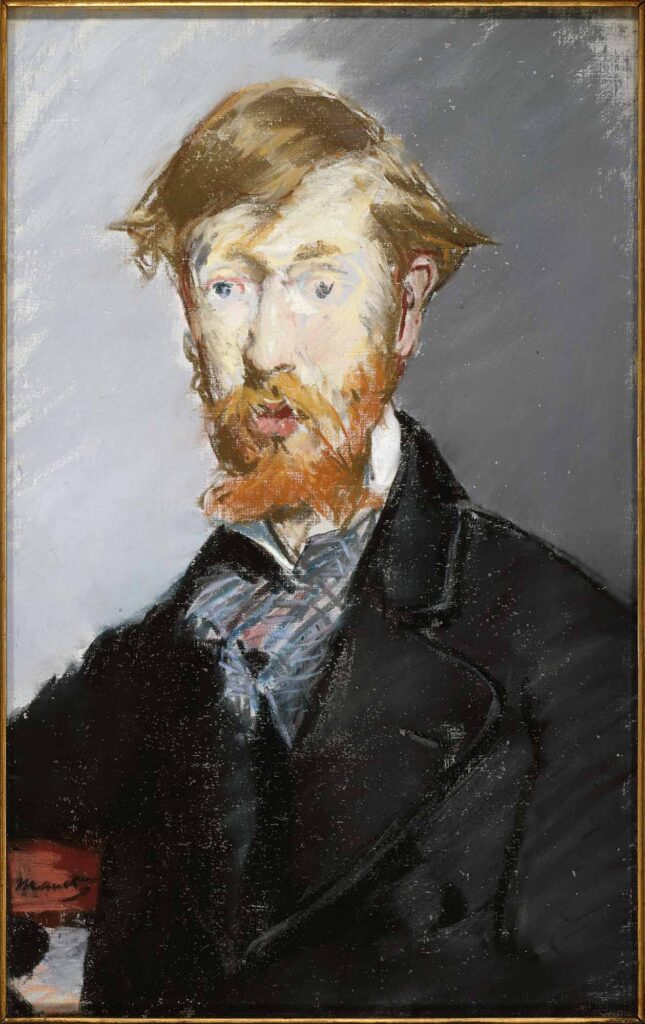

George Moore, pastel on canvas, 21 3/4 x 13 7/8 in.

Upcoming: Manet/Degas, September 24th, 2023 – January 7th, 2024, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

1

It’s probably reasonable to say Manet had a weakness for beautiful women, since he died of complications of syphilis. His weakness was also his strength. Women, especially attractive ones but not always, were the most compelling motif of his paintings and his perennial subject was the life, or lack of it, in their eyes. A naked woman’s glance toward her viewer became the core of the two paintings that established his reputation as the father of modernism: Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia. The scandal of the fact that the nudes in both paintings were probably also high-class courtesans, living off the generosity of their loyal sex partners (like Odette in Proust’s novel who rises to the highest ranks of Parisian society) announced Manet’s talent and deviously witty stance toward both the society and the artistic establishment of his day. The way he depicted the amoral world he saw in his high-class milieu looked transgressive to the arbiters of art. In reality, his paintings were good-humored satire on how modern life, as he experienced it, had little to do with the work being shown at the Salon exhibitions in Paris.

He was a truth teller with the heart of an outsider, and this outraged his contemporaries because in painting, nudity was expected to live within predictable narrative boundaries. In 1869, for example, Loudet’s interpretation of Cephalus and  Procris hung on the walls of the exhibition, an accomplished painting within the acceptable guard rails: an interpretation of the Greek myth in which one could pretty much plead to having painted bare breasts under duress because it was required by a noble Greek myth. This workaround enabled what could have passed for soft-core porn to get into the Salon and be received with respect. Fragonard had painted a more prurient vision of the story, a typically amazing bit of Rococco painting from him, and it was a subject many painters reprised.

Procris hung on the walls of the exhibition, an accomplished painting within the acceptable guard rails: an interpretation of the Greek myth in which one could pretty much plead to having painted bare breasts under duress because it was required by a noble Greek myth. This workaround enabled what could have passed for soft-core porn to get into the Salon and be received with respect. Fragonard had painted a more prurient vision of the story, a typically amazing bit of Rococco painting from him, and it was a subject many painters reprised.

The nudity of Loudet’s painting was justified by the story-telling. Manet gently mocked the whole process of smuggling nakedness into the exhibition under the guise of noble or spiritual tropes. While structuring his images in ways similar to the presentation of unclothed women in the past, he showed his figures in contemporary settings, women being naked for no reason other than to be naked, or to make a living that way. If Olympia had been embraced by the critics, it might have become the first unapologetic centerfold of its time, but actually it’s not even as tamely erotic as Fragonard’s lush, seductively-lit work. It’s realistic, not titillating, and thus it’s a funny contrast to all the other heroic presentations of breasts. Manet was shamed for his wit. Like his contemporary, Flaubert, he created a kind of realism that at first served to epater le bourgeoisie until he began to use it to express some of the most fleeting and elusive moments in human life. Moments in life live on his canvases the way they do later in movies or in candid, “street” photography. His snapshots were precursors of Gary Winogrand and Vivian Maier. This was his magic: to trap life in flight, and watch it seem to move in place, a butterfly in a jar. Early on, as a result of his notoriety, he became friends with other kindred rebels, Baudelaire and Mallarme as well as the Impressionists, a group whose work he studied but whose esthetic he never completely adopted.

He didn’t really fit anywhere, except in the company of Degas, whose work advanced alongside his. Manet lurked around the edges of what was happening, studying and using some of it. He couldn’t give himself over completely to the Impressionist preoccupation with the pleasures of atmospheric color. It wasn’t the MORE

March 20th, 2023 by dave dorsey

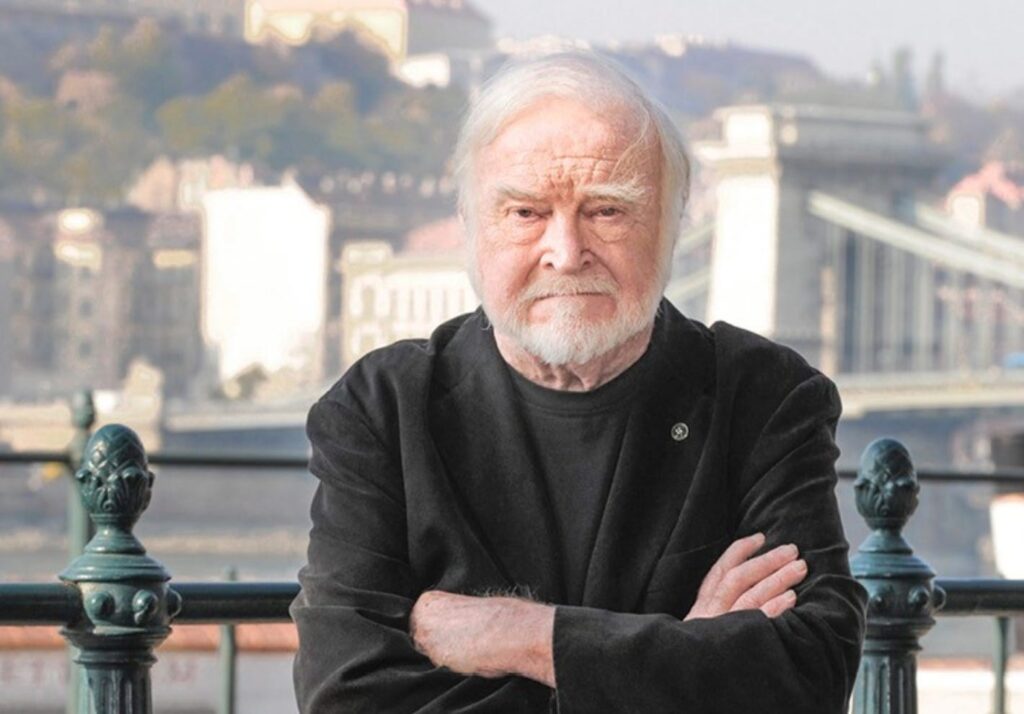

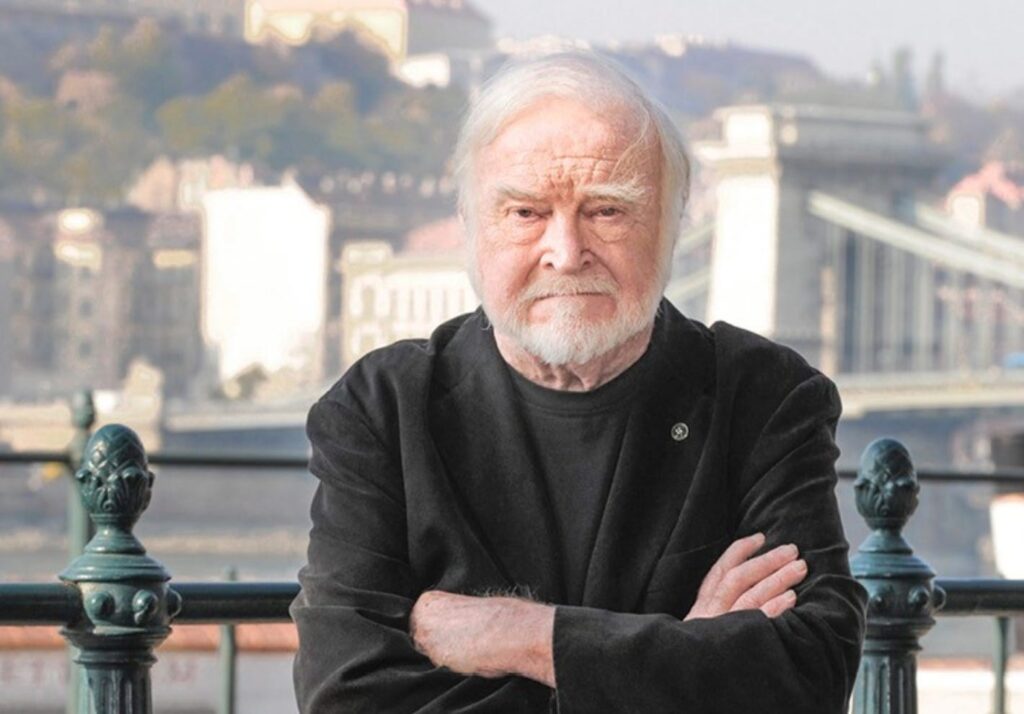

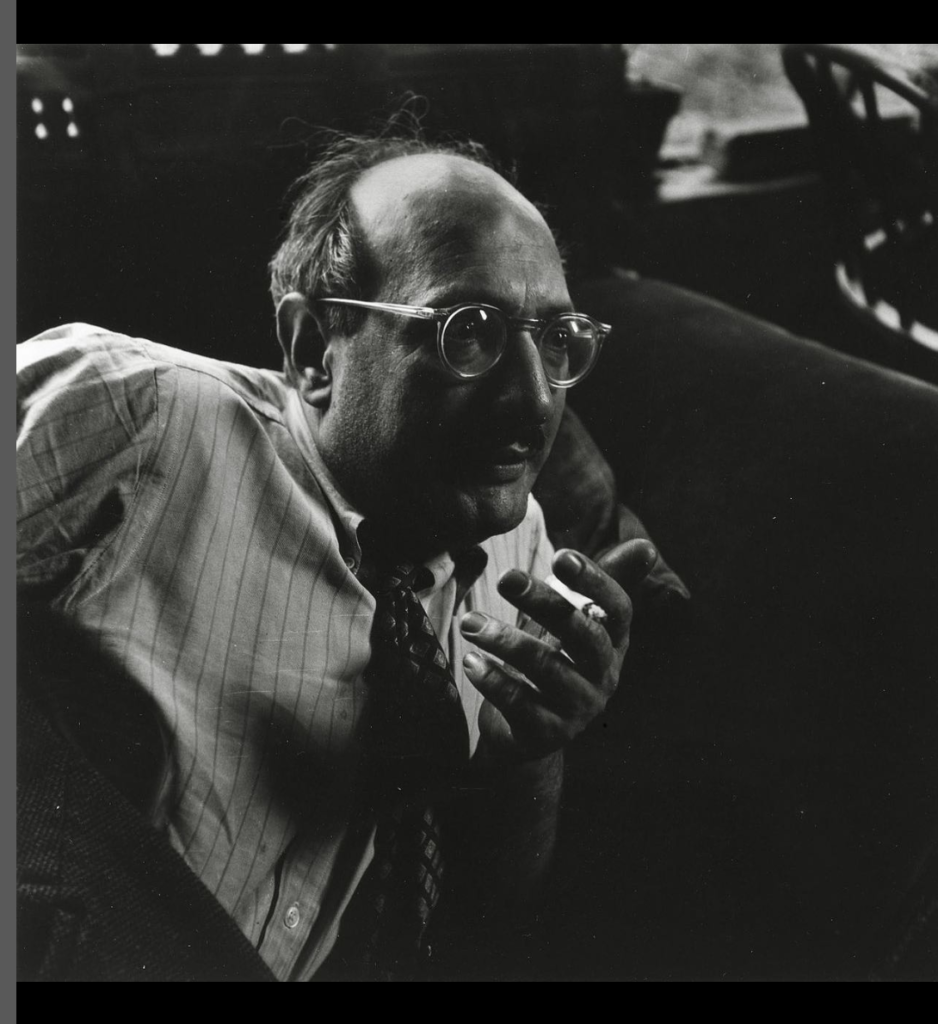

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, author of “Flow”, (1934-2021)

From the book Flow. The first quote describes probably the easiest, best justification for representational art, which is mostly about sustained attention for no motive but to pay attention and then acting on what it shows:

If you are interested in something, you will focus on it, and if you focus attention on anything, it is likely that you will become interested in it. Many of the things we find interesting are not so by nature, but because we took the trouble of paying attention to them. The second describes the transition from not-painting to painting on the average morning:

The optimal state of inner experience is one in which there is order in consciousness. … “Flow” is the way people describe their state of mind when consciousness is harmoniously ordered, and they want to pursue whatever they are doing for its own sake.

Most enjoyable activities are not natural; they demand an effort that initially one is reluctant to make. But once the interaction starts to provide feedback to the person’s skills, it usually begins to be intrinsically rewarding.

…success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue…as the unintended side-effect of one’s personal dedication to a course greater than oneself.

…It is when we act freely, for the sake of the action itself rather than for ulterior motives, that we learn to become more than what we were.

Now . . . we do studies — we have, with other colleagues around the world, done over 8,000 interviews of people — from Dominican monks, to blind nuns, to Himalayan climbers, to Navajo shepherds — who enjoy their work. And regardless of the culture, regardless of education or whatever, there are these seven conditions that seem to be there when a person is in flow. There’s this focus that, once it becomes intense, leads to a sense of ecstasy, a sense of clarity: you know exactly what you want to do from one moment to the other; you get immediate feedback. You know that what you need to do is possible to do, even though difficult, and sense of time disappears, you forget yourself, you feel part of something larger. And once the conditions are present, what you are doing becomes worth doing for its own sake.

…success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue…as the unintended side-effect of one’s personal dedication to a course greater than oneself.

March 17th, 2023 by dave dorsey

Some things have only intensified in the past 60 years. From the dailyrothko Instagram feed:

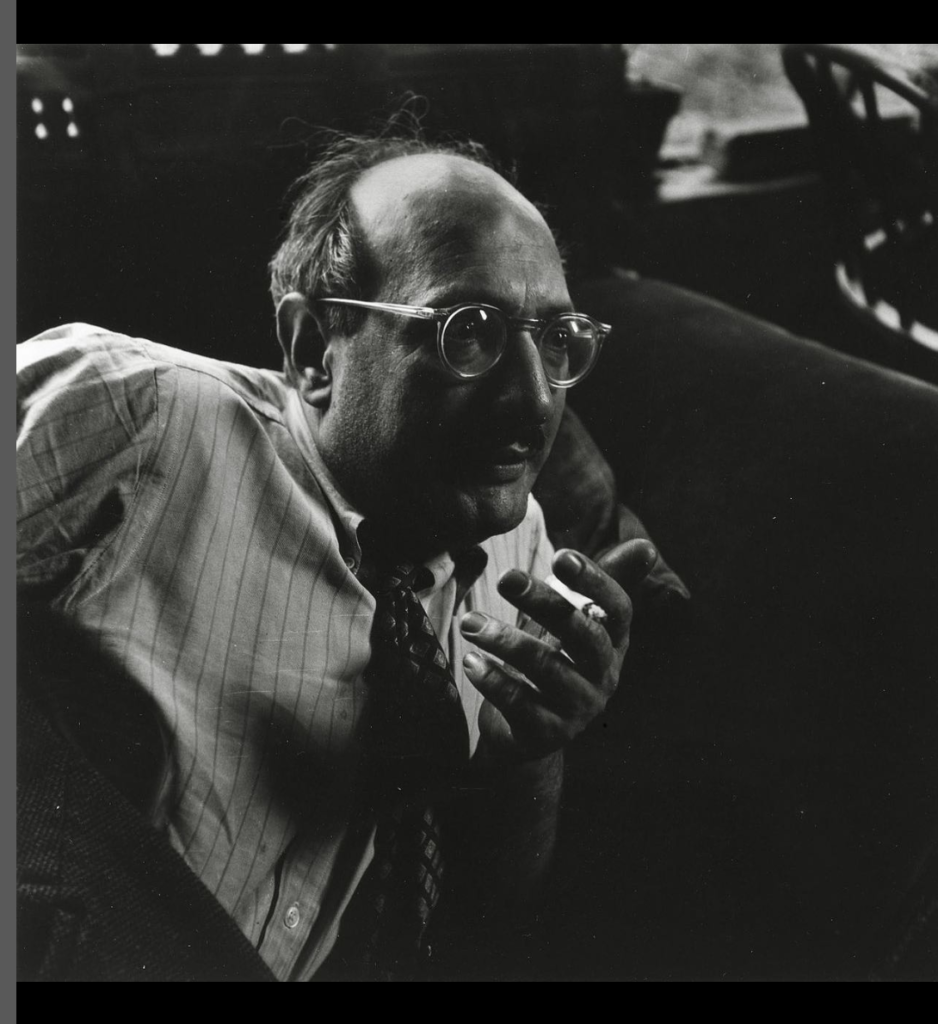

“When I was a younger man, art was a lonely thing. No galleries, no collectors, no critics, no money. Yet, it was a golden age, for we all had nothing to lose and a vision to gain. Today it is not quite the same. It is a time of tons of verbiage, activity, consumption. Which condition is better for the world at large I shall not venture to discuss. But I do know, that many of those who are driven to this life are desperately searching for those pockets of silence where we can root and grow. We must all hope we find them.”

– Address at The Pratt Institute, 1959

March 11th, 2023 by dave dorsey

Four Radishes July, detail, 4 x 10 inches, oil on panel, 2015

March 8th, 2023 by dave dorsey

David Baird, Still Life with Grapes, 12 x 12, oil on canvas

I’ve been observing this painting for weeks now, off and on, trying to deconstruct what I’m seeing and why I love it. It does many things quite orthodox within the methods of the perceptual painters, some of them I “feel,” as one might say, and others I find irksome when they seem to become affectations and tics. He avoids everything irksome here even while engaging in a couple of the tics.

He’s another extremely talented alum of the Jerusalem Studio School, and he isn’t alone among painters who have studied there in that the quality of the paint he applies, for me, gives the sense of being mixed right from the tubes, without additional medium, so that it affords what seems like a dry, ragged texture, almost like pastel. The unfinished edges, which can seem like an affectation (one that I usually like until it looks studied), feel natural and serve his composition by echoing the tone of the bowl and the inverted soft-boiled egg cup—an object he has used repeatedly, going back to it the way Chardin kept using the same household tools from one painting to the next. That ragged border of raw canvas shows, in the gauzy and yet abrupt shift from paint to untouched canvas, what appears to be a low ratio of linseed oil to pigment. All of this sounds like shop talk, and I may be completely wrong about his mixing, but he is using this quality of paint to convey light and color in a way that’s deeply felt and sensuous. His tones are rich and beautiful and in perfect harmony. His very limited range of color is there to offer itself up for its own quiet virtues, not just to serve the purpose of representation.

Baird’s umber in the upper right corner, just leaning toward olive recedes obediently almost as negative space, a little glimpse of taupe wall that offers a ground for the objects closer to the viewer, but it’s also a hue that comes alive in juxtaposition with the reddish surface just below it that draws its harmonies from the grapes. Together, they are luscious colors that don’t call attention to themselves at first, but offer subtle pleasures to an insistent gaze. The geometry of this still life—the sphere, the rectangle of the MORE

March 5th, 2023 by dave dorsey

Stuart Shils, while traveling in ancient lands, rag paper, likely watercolor

The whole point of study… is to stand before the world in awe…

–www.stuartshils.com

I’ve been following Stuart Shils since I discovered him when he was juror for an annual group show five years ago at Prince Street in Chelsea. He’s one of the most consistently rewarding painters to follow on Instagram. He’s prolific as well, which makes him perfect for the ravenous maw of social media, but he’s able to keep the feed flowing with regular posts because much of his work is small and appears to be quickly executed, each painting seemingly just a freeze frame from an ongoing flow of paint. One of the aspects of his own Instagram stream that makes it unusual, if not unique, is that for a while it seemed to become a work of art itself, not just a way of sharing images of work done elsewhere: it was more or less the medium for his abstract photography. I could imagine buying a print of one of his photographs, but photography has been democratized to the point where it’s mostly digital now and exists in the ether as much as anywhere else, so when his shots appeared, they seemed to have their being there in that stream of images and nowhere else.

In those shots he was seeing the way he sees when he makes a painting: the photographs often had all the formal concerns and the feel for composition that magically give his paintings such a haunting quality of remembered immediacy, yearning and loss, shot through with a passion for color.

Most recently, he’s been proving that what he does may look like color field improvisation, but it’s also figurative in a broad sense: in extremely subtle ways, it represents the visible, physical world. It’s just as much about the ambiguous interplay of figure and ground as his earlier more quickly recognizable work. Lately, he’s using Instagram to create a diptych by pairing two paintings from twenty years apart, or thereabouts. In the earlier, one can usually recognize the image at a glance. In the more recent work, it takes a while to see how the gestural paint both reveals and conceals the figure. Often, it can take some extended looking to decipher what you’re seeing, or might be seeing. In the pairings, he offers one painting from around the turn of the current century and another from the MORE

March 2nd, 2023 by dave dorsey

THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY, 2018, oil on linen, 15 3/4 x 15 3/4 inches

The unfinished quality of Kelley’s work is part of its appeal, especially when the untouched white canvas creates a balancing tension with the white cloth, though after a while with his paintings it begins to feel like an affectation. The fascination for me is how he gets that matte texture that seems to be everywhere, even when it’s evoking a gently shining pear. Four colors plus black and white. It’s as if he first applies Gesso a few times to raw canvas, and it’s so absorbent that it draws all the oil out of the paint leaving that luxuriant suede-like surface. The modeling of the cloth is a pleasure, as if he’s stenciling some of those creases and applying a mist of paint over them. The little white lines in the purplish bruise of shadow at the bottom of the cloth look like beetle trails in firewood. His titles can be even more recherche and quirky than Shils’.

Procris hung on the walls of the exhibition, an accomplished painting within the acceptable guard rails: an interpretation of the Greek myth in which one could pretty much plead to having painted bare breasts under duress because it was required by a noble Greek myth. This workaround enabled what could have passed for soft-core porn to get into the Salon and be received with respect. Fragonard had painted a more prurient vision of the story, a typically amazing bit of Rococco painting from him, and it was a subject many painters reprised.

Procris hung on the walls of the exhibition, an accomplished painting within the acceptable guard rails: an interpretation of the Greek myth in which one could pretty much plead to having painted bare breasts under duress because it was required by a noble Greek myth. This workaround enabled what could have passed for soft-core porn to get into the Salon and be received with respect. Fragonard had painted a more prurient vision of the story, a typically amazing bit of Rococco painting from him, and it was a subject many painters reprised.