Archive for the 'Uncategorized' Category

January 27th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Head with Fabric, David Baird, Birmingham, Alabama Oil on canvas, 2020

David Baird had three paintings in Manifest’s Painted exhibit to kick off their 18th season in Cincinatti. This one, Head with Fabric, has many of the fine qualities of his painting, Red Nude, that just took First Prize at the Salmagundi Club’s New York Figurative Show. His handling of paint in the way he renders a figure reminds me a bit of Degas, which is high praise: the soft glow and gradual transitions among tones without being obsessive about detail while conveying the living quality of flesh–his figures breath. You feel you can take their temperature. But what makes his paintings so astonishing is the variation in level of verisimilitude, moving from persuasive illusions to flat patterns and roughly unfinished portions of canvas without destroying the overall feel of space and depth. Diarmuid Kelley has been doing this, to a lesser degree, for a while now, but without creating as much interesting tension between the finished/unfinished, illusionistic/flat areas of his canvases. It’s something Baird has in common with other painters who have connections with the Jerusalem Studio School. Some of Baird’s still life objects work both as fuzzy abstract areas of tone and as soft but utterly convincing visions of objects in three-dimensional space. The color is usually a range of rich, gorgeous earth tones worthy of Braque. It’s hard to figure out precisely how he does it. That usually wins my highest respect, when the technique seems utterly impossible to reverse-engineer.

January 24th, 2022 by dave dorsey

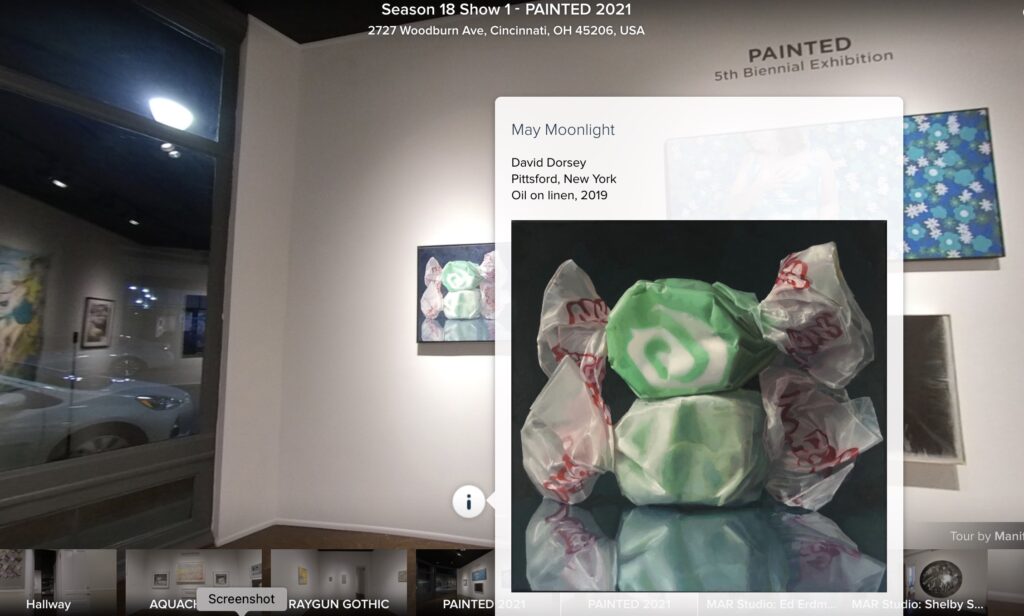

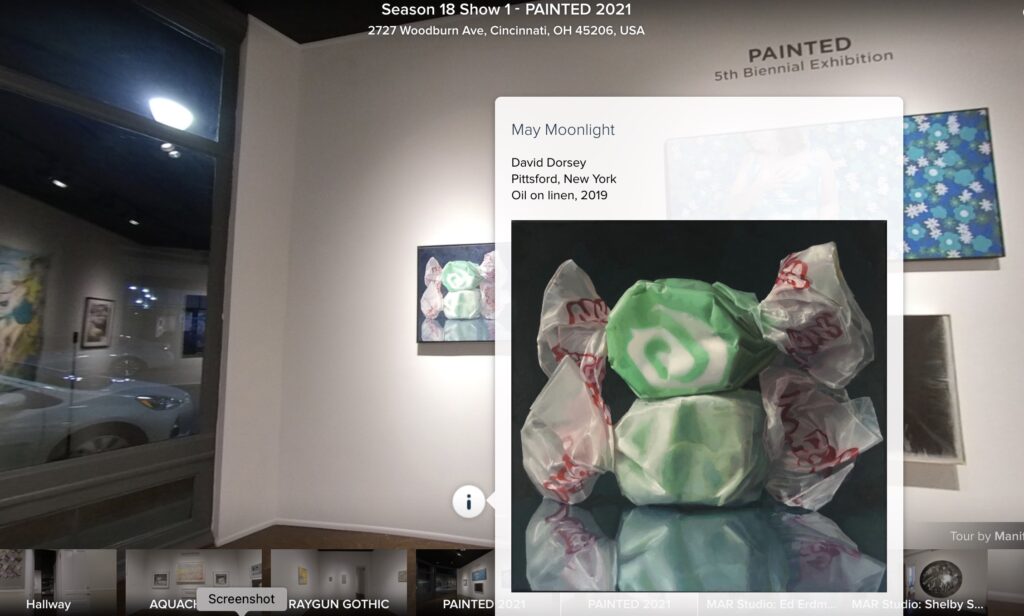

An online view of Manifest’s Painted exhibition last fall.

I’m way late posting this screen shot from last fall’s Painted show at Manifest in Cincinnati. The online portal allowed a viewer to click and scroll through every gallery at Manifest, all of the shows mounted there, with the ability to swivel 360-degrees, Google-maps style. You could use your touch screen or track pad or mouse to look in any direction from any station in the sequence of click-to spots that walked you through the show. Every gallery and museum should do this, at least the ones not dependent on admission fees for survival. I clicked on the info icon and up popped the image of the painting with all the identifying data. Very cool and it helped make up for the inability to attend.

December 21st, 2021 by dave dorsey

Where Did It Go?, Bradley Butler, 8″ x 10″, acrylic on panel

Bradley Butler’s recent solo exhibition at Williams-Insalaco Gallery 34 at Finger Lakes Community College was a quiet thrill. The work is quietly evocative, simple, deeply felt and as ontologically disorienting as a Beckett play. He took his title from Pet Sounds, Brian Wilson’s groundbreaking album: I just wasn’t made for these times. Many of his titles were equally candid in their unknowing vulnerability: I Don’t Know What I’m Doing Here and I Want to Believe in Something. His dark, mysterious landscapes—Turner meets Giorgione meets David Smith’s Hong Kong paintings—evoke a multitude of perceptions that hover just below the reach of the intellect. They are extremely simple in their execution. He uses black, white, thalo ted and thalo treen, and his brushwork remains mostly uniform across the canvas. He reduces his methods to the fewest possible choices and still comes up with a broad array of images that seem to straddle the border between one’s inner life and a twilight world of mountainous space, all of them looking consistently primordial. He seems not to want to assume to know more about existence than what prevailed before the first few words of the Book of Genesis. The way he gets so much variation out of such a paucity of tools reminds me of a guitar lesson I had in my teens when my instructor told me to riff for five minutes, without repeating myself, against a minor seventh blues chord progression by using only three notes. There were, to say the least, a lot of long, expressive pauses. Butler, in his relatively small canvases, creates a sense of vast reaches of an undiscovered world. It beckons and invites you to venture past a corner that juts into view, but also makes you hesitate, unsure what you are going to find. I posted one of his paintings on Instagram and simply quoted a passage from Lao Tzu as commentary:

Something mysteriously formed,

Born before heaven and earth.

In the silence and the void,

Standing alone and unchanging,

Ever present and in motion.

Perhaps it is the mother of ten thousand things.

I do not know its name.”

I disagree with Butler’s show title though. His work seems perfectly attuned to his times, being an example of an honest uncertainty and humility that would go a long way to being an antidote to the cloud of knowingness that cloaks how people communicate now. Anyone interested in seeing Butler’s work can find him most days doing a remarkable job of showing excellent art at his gallery, Main Street Arts in Clifton Springs, where a fascinating national juried show of small workswill be up until the Dec. 23rd.

December 19th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Scott Noel, Still Life with Pennies and Shell, 30″ x 24″ 2021

From Matt Klos at Exeter Gallery (241 S. Exeter St., Baltimore MD) a solo exhibition, “Still Life”, of Scott Noel’s recent paintings running through the end of the month. His remarks about color are on point. Noel’s paintings have a colorist’s skill with tone and hue. Once you recognize that little red action figure in the center of Still Life with Pennies and Shell, above, all the other colors in the painting are anchored and vivified by it:

Scott Noel has lived, painted, and taught in Philadelphia for most of his professional life. He has inspired generations of painters through his teaching at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) since 1996. His subjects range broadly from figure, cityscape, domestic scenes and gardens near his home in Manayunk, studio interiors, and still life. His painting methods harken to traditional methods of American painting related to artists such as Thomas Eakins, Edwin Dickinson, and Charles Hawthorne although he creates color spaces that register as something contemporary, and perhaps, even indicative of an upbringing in the 60’s in Charlotte, NC.

This exhibition features ten oil on linen paintings, eight painted within the last year. Noel’s painting practice is unrelenting, and his output is abundant. His method of working “allover” in long, sometimes eight-hour sessions, is necessary since he’ll often scrape away his initial marks to serve as a platform for subsequent moves. In this way he keeps the image fresh and walks the line between delicate descriptions and unresolve. His mastery of painting is apparent yet there is nothing insincere or aloof about his work. He is seeking to understand what lays before him and seems to approach his latest works with a touch of naivety and all the joy he finds in his craft.

Scott Noel’s exhibition at Exeter is his first exhibition in Baltimore and coincides with his solo exhibition at Gross McCleaf Gallery in Philadelphia, Current Events, Provisional Painting. He was born in Charlotte, NC in 1955, educated at Washington University, St. Louis. Noel has written catalogue essays about forbears and peers that include Lennart Anderson, Larry Day and Ben Kamihira. His work is in numerous collections including The Woodmere Museum, Lasalle College Art Museum, The Pennsylvania Convention Center, and Drs. Don and Allison Innes.

December 1st, 2021 by dave dorsey

Chad, making his debut in the novel, coming into the balcony at the theater occupied by Strether. Illustration by Leslie Saalburg.

It might be fun and profitable for someone—if college students still read Henry James—to translate his late novels into English. I read The Ambassadors in graduate school, as required, and absorbed little of it. It was a compulsory title. The problem was that I wasn’t prepared to pay enough attention to actually locate subjects and verbs. It’s often a challenge in The Ambassadors. Over the past several years, as I’ve attempted to read or reread all of James’s novels, I’ve struggled to find the right adjectives to describe this late prose style: elliptical, disembodied, ethereal, circuitous, evasive, a sort of private murmur of abstracted assertions that seem to exhale the aura of his protagonist’s awareness rather than simply tell the reader what in the world is going on. Henry was offended when his brother, William, reacted to The Golden Bowl, the novel James published directly after The Ambassadors, by saying he admired its brilliancy but would have preferred an “absolute straightness of style” rather than “the method of interminable elaboration of suggestive reference.” William was being tactful: his observation more or less sums up how annoying these novels can be. And yet they are addictive once you succumb to the challenge of deciphering the prose. They tease you into submission. It can be amusingly, ridiculously frustrating to fish in the dark lake of this prose for what a given sentence signifies, especially when—fish in creel —you realize you could have netted one just as nourishing from inside an easily plumbed aquarium of the sort built by the earlier Henry James himself.

Lambert Strether is the central “ambassador” in the book. He has been sent to Europe by Mrs. Newsome to retrieve her son, Chad. She owns and runs a lucrative industry in Woollett, Massachusetts, and she wants him to lead it into the future. Ostensibly, Chad has been seduced by an immoral woman, maybe even a woman “of the streets.” Fears about this mysterious woman’s antecedents are groundless. She’s an aristocrat. Chad has been transformed into a genteel, poised, Parisian courtier by his association with Madame de Vionnet and her daughter, Jeanne. He has become a bit like Swann, from Remembrance of Things Past, twenty years ahead of Swann’s emergence in Proust’s novel. Strether must convince Chad to come home because his mother wants him, effectively, to run the company with a focus on the new world of advertising—a force that, it’s surprising to learn from this novel published at the turn of the 20th century, was already fueling commerce.

From the moment he arrives in Europe, Strether falls in love with his surroundings, and finds himself—in his own version of a mid-life crisis, in his fifties—falling, not for the first woman he meets (who falls in love with him, as it happens) but for Europe and, especially Paris itself. When he meets his quarry, Chad Newsome, he recognizes that Chad has matured and come into focus as an accomplished social creature in ways Strether never would have guessed were possible from his acquaintance with the boy while he was growing up. Strether’s imagination opens to Paris, the magnificence and subtle elegance of the shops and houses, the left and right banks of the Seine, the Faubourg St. Germaine, the parks and the museums, the restaurants, the hotels, and the everyday sounds that rise from the streets. The world has been renewed before his eyes. His impulse is to wander and absorb everything he sees, smells, hears and touches. He’s reborn. Through this febrile, almost manic hunger for the city and the region, he’s only half-aware of how the seemingly innocent seductions of a beautiful place color his perception of the relationship between Chad and this lovely, charismatic and slightly older woman. Marie de Vionnet is a countess, highly intelligent, sensitive, humble, the model of noblesse oblige. All of Strether’s actions arise from his desperate faith that her relationship with Chad is virtuous, chaste, a model of Platonic devotion and friendship. She is married but estranged from her husband and Chad’s family suspects adultery, hence the need for Strether to bring the son home. Yet, from the beginning, Strether is charmed by both Chad and the countess and immediately begins to resist his mission, the call of Woollett. His motives for temporizing are a complex mix of selfishness and generosity—he wants to dwell in Paris as long as possible to absorb its glory. This requires Chad to be morally pure. If Chad’s love for this woman and her daughter were base, it would break the spell of Paris itself, destroy the aura of nobility. It would be the serpent and apple in this garden. The garden itself would cease to charm. This would obligate him to bring Chad home by any means possible, ending the entire European idyll. His actions throughout most of the book are based on Strether’s desire for this new, improved Chad to MORE

November 19th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Night Walker, Jim Mott

It’s the last week to see Jim Mott’s excellent work from a unique project, Life Studies, a modification of his usual itinerant mode, where he travels to a city like Ferguson, Missouri and paints scenes from the life of his participating host, as a gift in exchange for lodging. In this case, he has painted multiple scenes that mattered to a woman who lives here in Rochester. About “Night Walker”, he says:

One of the paintings in my current show at the Yards – done after exploring Ridgeway Avenue at night a couple of weeks ago. This is in the area of Sacred Heart Cathedral – where my project collaborator, Sonja Rosario, was baptized and where one of Rochester’s 50+ fatal shootings of 2021 occurred earlier this year.

At THE YARDS – Jim Mott’s 2021 NYSCA project exhibit runs through Nov 28, Saturdays 10-1 and by appointment. Jim will give a talk about his practice on Nov. 20 from 5-7 pm. “Featuring the results of my 2021 NYSCA Grant project, Life Studies is a collection of paintings and stories based on collaborative sketch outings with Sonja Rosario Belliard, a creative individual and young mother from northwest Rochester. The images and words represent places of significance to her life.”

November 6th, 2021 by dave dorsey

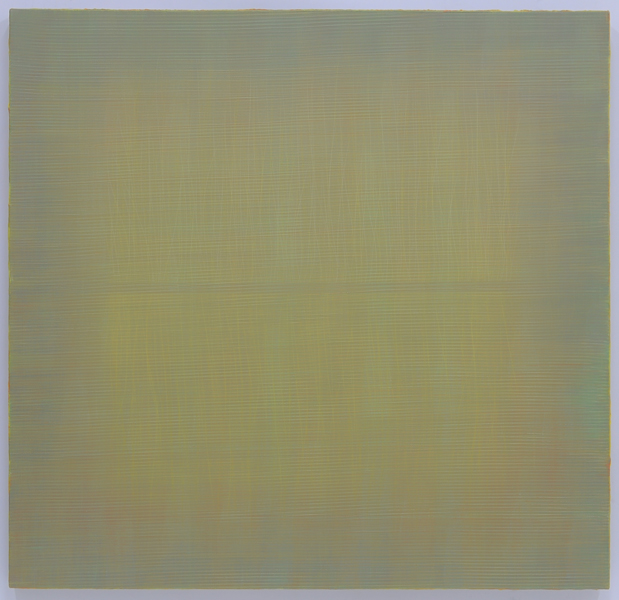

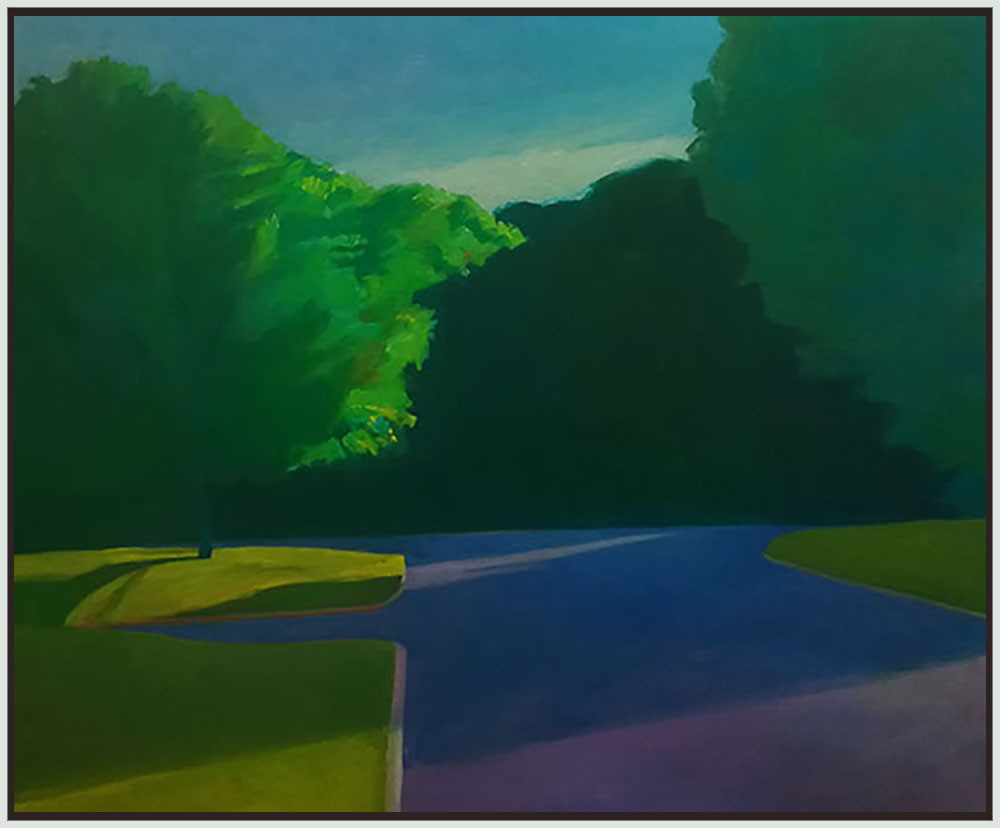

My submission for the Oxford show, April Dawn, oil on linen, 52″ x 52″. Sold.

At the opening reception for “In a Different Light” at Oxford Gallery Saturday, from 5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m., you’ll be able to get a glimpse of one of the best themed group shows Jim Hall has organized. Nearly all the work is rewarding and some of it is remarkable and surprising. Tom Insalaco has been working for years on a series of paintings showing city traffic at night, almost an extreme reduction of his usually dark motifs into two-tone compositions that either look like a procession of ghostly headlights or sinuous lines of stars against the black ground of the urban night. In Night and Light, the title emphasizes the stark juxtaposition of blindingly bright light against almost featureless darkness. Yet this potentially bleak darkness comes across as familiar and alive: two figures, perfectly rendered in the half-light, watch the passing cars and make the viewer feel like another pedestrian enjoying the night’s energy. It’s as ordinary as a remembrance of a late walk to your room in New York City, but also suggestive of the anonymity of city life in a spiritually-isolated age.

Insalaco has been working for years on a series of paintings showing city traffic at night, almost an extreme reduction of his usually dark motifs into two-tone compositions that either look like a procession of ghostly headlights or sinuous lines of stars against the black ground of the urban night. In Night and Light, the title emphasizes the stark juxtaposition of blindingly bright light against almost featureless darkness. Yet this potentially bleak darkness comes across as familiar and alive: two figures, perfectly rendered in the half-light, watch the passing cars and make the viewer feel like another pedestrian enjoying the night’s energy. It’s as ordinary as a remembrance of a late walk to your room in New York City, but also suggestive of the anonymity of city life in a spiritually-isolated age.

Elizabeth Durand’s Shoreline Light, at etching monoprint, shows how much she has continued to push her work toward a sort of abstraction that somehow looks wonderfully accurate in the way it  conveys the rich warm color of a setting sun over a strip of land and sea, all of it minimally indicated, yet rich with carefully applied color and brushwork that somehow passes for cloud formations but also looks expressionist and gestural. She has been making art for many decades, and now late in her life is still innovating as a quietly original and masterful print-maker whose feel for color has always been superlative.

conveys the rich warm color of a setting sun over a strip of land and sea, all of it minimally indicated, yet rich with carefully applied color and brushwork that somehow passes for cloud formations but also looks expressionist and gestural. She has been making art for many decades, and now late in her life is still innovating as a quietly original and masterful print-maker whose feel for color has always been superlative.

In an utterly unique contribution to the show, Barbara Page has interpreted a small library of books in visual terms. It’s the outcome of an epic endeavor to create a personal card catalog of 800 different books. Using blank library lending cards, she covered 800 of them with the title and author of each book then a unique work of art to visualize the book’s content in the spaces where borrowers would normally sign their names. The drawings are funny, clever, touching, and sometimes mysterious. All of them are either lively, lovely, or both. One of her contributions to the show is a copy of the book she published offering readers a catalog of the art work itself, and it was accompanied by a digital print of some of her favorite cards, as well as the two drawers containing all of the 800 original works. One could spend days poring intermittently through her efforts, giving each title the attention it deserves.

author of each book then a unique work of art to visualize the book’s content in the spaces where borrowers would normally sign their names. The drawings are funny, clever, touching, and sometimes mysterious. All of them are either lively, lovely, or both. One of her contributions to the show is a copy of the book she published offering readers a catalog of the art work itself, and it was accompanied by a digital print of some of her favorite cards, as well as the two drawers containing all of the 800 original works. One could spend days poring intermittently through her efforts, giving each title the attention it deserves.

One of my favorite paintings in the show is Amy McLaren’s “Democracy.” I didn’t look at the title when I saw the painting at Oxford, and today when I spotted my photograph of it on my iPhone, I thought, “This is either about marriage or politics.” Then I saw the title in Jim’s price list and laughed. It is a funny painting—it shows what appears to be a white rooster running toward the left with a small group of black roosters running toward the right, the group clearly running away from the lone rooster and vice versa—as a metaphor of cluelessness of our contemporary political luminaries. But it’s a haunting image, and the faint light that falls on the agitated fowl bathes them in a sad kind of wisdom, as if this flight makes visible the universal human desire to flee the truth in a fading light that makes this possible and only fades faster because of it. The image transcends its MORE#

thought, “This is either about marriage or politics.” Then I saw the title in Jim’s price list and laughed. It is a funny painting—it shows what appears to be a white rooster running toward the left with a small group of black roosters running toward the right, the group clearly running away from the lone rooster and vice versa—as a metaphor of cluelessness of our contemporary political luminaries. But it’s a haunting image, and the faint light that falls on the agitated fowl bathes them in a sad kind of wisdom, as if this flight makes visible the universal human desire to flee the truth in a fading light that makes this possible and only fades faster because of it. The image transcends its MORE#

November 4th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Season of Plenty II, Caitlin Winner, oil on canvas, 65″ x 67″

Note: I was honored to be included in Manifest Gallery’s Painted biennial, an international survey of new painting, yet the show came and went before I had a chance to write about it. A week ago, though, near the end of the exhibit, I participated in a Zoom call with 15 or so of the artists showing at Manifest, including a few from the collateral exhibitions: Jason Bly to talk about his solo show and some painters from the galleries concurrent overview of exceptional recent watercolor painting. It was a stimulating discussion that ran into the evening for those of us on the Eastern side of the country, exciting partly because the work from these artists is among the best Manifest has gathered for Painted, and also because some of the artists were exceptionally articulate. I felt tongue-tied much of the time as I tried to speak briefly about what I’ve been able to write about more fluently in these posts. There’s almost no work in the show that didn’t impress me at one level or another, sometimes to the point of envy and sometimes despite my own aesthetic preferences. I’m going to try to post work from these painters every few days, alternating with paintings from the current group show at Oxford Gallery here in Rochester. I was so impressed by one painter in particular, I reached out to her and got some interesting answers to the questions I posed. This post is based on my response to her painting and what she wrote back.

Caitlin Winner works very slowly and deliberately, putting in more time on her paintings than nearly anyone I know. It shows in the strength of the results. Two of her large canvases were included in Manifest’s Painted exhibit in October, and they take perceptual painting to a place I love. I admire the work of most of the perceptual painters, though I think of it as a larger aesthetic space than do its primary practitioners, and I would include in its ranks painters whose work doesn’t exhibit many of its most familiar stylistic hallmarks—and aren’t usually considered part of the club. Above all else, Winner is an exceptional colorist, which I think sets her apart from much of the “perceptualists,” whose color is often remarkable but more subservient to other ends. Erin Raedeke’s paintings of birthday party detritus from a decade ago have been an exception, achieving a rare and delicate touch in the selection and use of color almost for its own sake. Yet color is boldly front and center for Winner in a way that isn’t the case with people like Zoey Frank and many others in that growing collective. I think of color as one of many equivalent formal tools most of the perceptual painters use to create a way of seeing that hovers between abstraction and representation, creating a sense of temporal disorientation, so that the past seems to move into view, blurring the contours of the present moment, creating what feels like the inexactitude of remembrance. David Baird, whose paintings were hanging beside Winner’s in the Manifest exhibit, offers an astonishing example of this: the gorgeous, autumnal tones of his images work to reinforce a dreamlike sense of temporal dislocation. Yet even with Baird, color—masterfully chosen—is on an equal footing with shape, value, line, and so on.

With Winner, as with someone like Louisa Mattiasdottir and Fairfield Porter, in October Interior, color becomes almost the overarching visual mission itself, with all the other formal qualities in a subservient role, even though so much else is going on in her devotion to the figures she shows the viewer: family and close friends who enriched her life during the pandemic’s most isolating months. The precision and clarity of her line also distinguishes her from many of her peers. Eve Mansdorf talks about the importance of edges, but clearly defined edges aren’t a mainstay for most perceptual painters who tend to elide and obscure the transitions between figure and ground. Winner’s outlines could have been drawn with a pair of scissors inherited from Matisse. The edges in her work bring to mind the clarity and definition of geometric abstraction from the 1960s. Her canvases have the translucent luminosity of watercolor, even though the oil is undoubtedly layered and opaque. Her color is intense and radiant, heighted by juxtapositions of complementary tones, but it nonetheless offers a visually accurate sense of immediacy in the way direct sunlight falls onto an outdoor scene. It’s almost impossible to capture the radiance of a bright summer day with photography, which favors the magic hour, early or late, when sunlight is diffused into the air, for bringing out the most vivid color without losing definition in the shadows. Yet here the relentless, high sun casts no colorless, murky shade. Foliage on the far side of a lake becomes a uniform curtain of beautiful green, a block of distinct color, as saturated in tone as anything in the foreground. Everything is crisply defined and drenched with color, like an old Kodachrome slide on a light table—it’s the light of the Impressionists—yet her figures are solid physical presences cut cleanly from their surroundings, not simply extensions of it, except in the way their color harmonizes with and enriches the color of what’s around them. Her kitchen interior works the same way: everything glows with color and light, nothing lost to shadow, no highlights overexposed, as inevitably the lights and darks would end up in a snap shot of the same room. MORE

October 29th, 2021 by dave dorsey

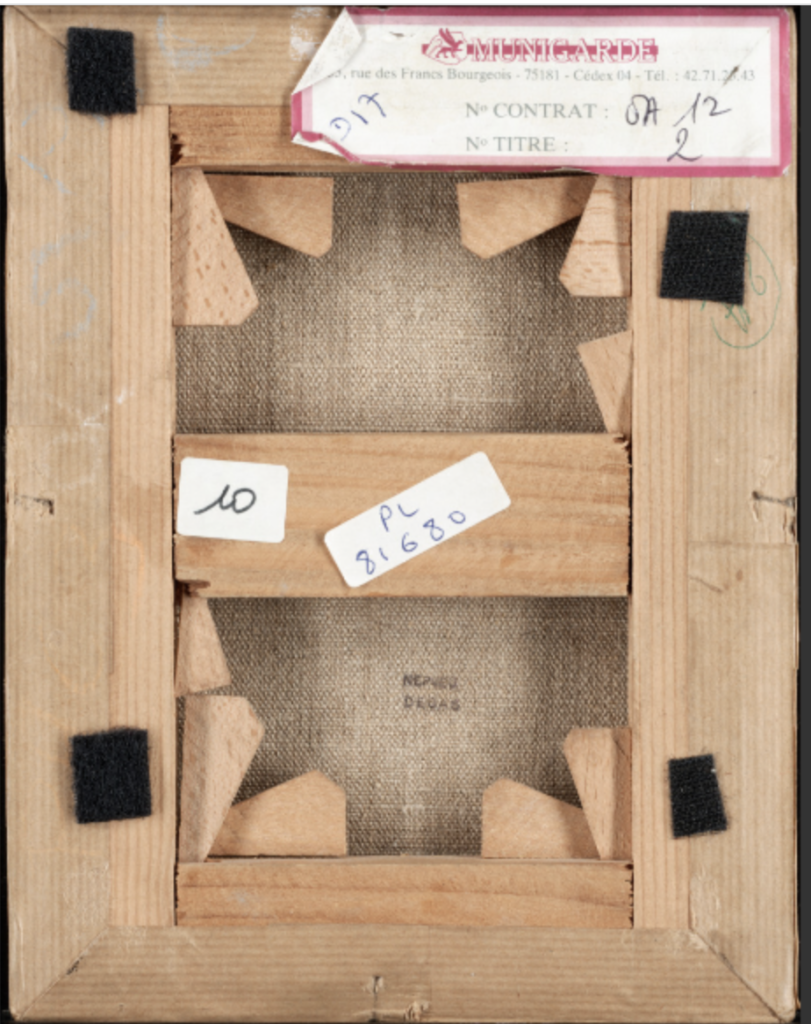

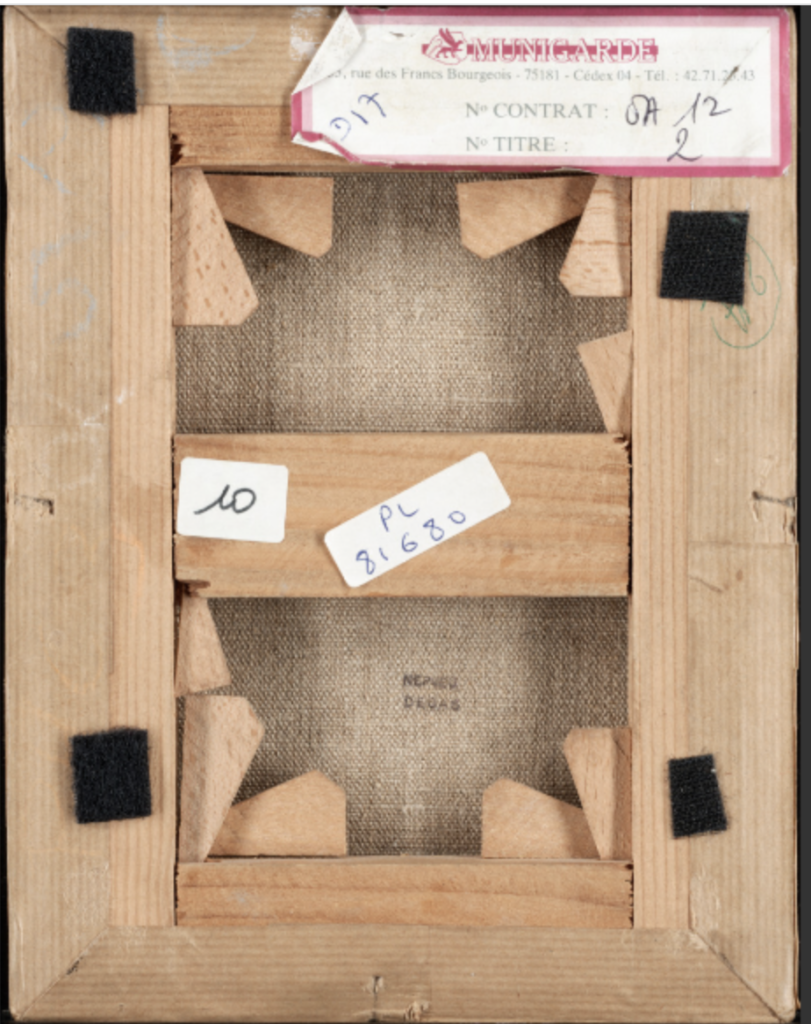

This is the verso view of the Degas self-portrait at the Getty. I was surprised at how many stretcher bar “keys” were wedged into every available joint in the wood to tighten it up. I generally use them as a last resort, keeping the surface flat by using different kinds of linen canvas for larger paintings than for small, unfastening the canvas and restretching, and so on. The problem I’ve had with this method is that the wedges loosen up in transport so that a tightly stretched canvas comes out of the crate a little slack by the time it arrives at a show. Also surprised that such a relatively small painting would need this much attention: smaller linen canvases tend not to loosen up in a visible way in my experience. It’s a pleasant surprise to see how a 160-year old painting looks almost brand new from the back: maybe because some comparatively recent attention was given to restretching it on new wood. It would be interesting to see how someone would do this job in such tight spaces behind the canvas.

October 23rd, 2021 by dave dorsey

Rod Penner, 290 East Brenham TX, acrylic on canvas, 32″ x 48″, detail

1

There’s a sense in which Vermeer’s interiors have an aura similar to that of a religious icon. There is little that’s explicitly religious in Vermeer’s subject: civilized, upper-middle class life in a culture where capitalist wealth was generating a new quality of life and an economic environment where painting could thrive. You can look at other work during the same period and be astonished at the quality, but in Vermeer, something unique emerged, this ability to convey the most ordinary moments in a tranquil, prosperous household as if they were eternal, blessed, somehow transfigured by ordinary sunlight through a leaded glass window. In a certain sense, Vermeer used purely esthetic means to awaken an ethical sense in the viewer—ethical in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s broad and slightly unconventional sense of the word. He opens his lecture on ethics with a startling assertion: “Now I am going to use the term Ethics in a slightly wider sense, in a sense in fact which includes what I believe to be the most essential part of what is generally called Aesthetics.”

He goes on to explicate what he’s attempting to say:

Now instead of saying “Ethics is the enquiry into what is good” I could have said Ethics is the enquiry into what is valuable, or, into what is really important, or I could have said Ethics is the enquiry into the meaning of life, or into what makes life worth living, or into the right way of living. I believe if you look at all these phrases you will get a rough idea as to what it is that Ethics is concerned with.

If you have read enough Wittgenstein, you would recognize that he is saying things that he, in other contexts, would call nonsense. This is not a pejorative term for him. It’s fundamental nonsense. To enquire into the “meaning of life” is to do something of almost grave importance, something he highly respected—as a threshold for living properly. (He would undoubtedly go on at length about the various implications of saying “properly” here.) This was, more or less, the mission of Socrates, to use reason as a ladder at the top of which you step off to live a good life, in the ethical (and also esthetic) sense of the word. It’s not a coincidence that Wittgenstein was the most Socratic of all Western philosophers since Socrates. He taught and philosophized by thinking along with his students, and he published only one book—which actually ought to draw comparisons to the pre-Socratics in its epigrammatic form—in his lifetime. What good means in this context is essentially indeterminate, inexpressible, but that doesn’t mean that it’s relative or subjective. Wittgenstein understood that to assert “I need to know the meaning of life” is to say something accurate and meaningful about a pursuit of nonsense—in his usage of that term. You are saying something about yourself that can be verified in a sense, so that the sentence itself has reasonable content about you, but the phrase “meaning of life” isn’t a signifier for which there are corresponding facts in the world. If the world is “everything that is the case” or the sum total of all facts, and logical thought consists only of propositions about the world that can be either true or false, then a phrase for which there are no corresponding facts is not logical; it is nonsense. And yet the fact that the phrase exists, that people use it, shows something that the words themselves cannot say: it “shows forth” the universal human urge to say what isn’t sayable, to think what can’t be thought—to discover, as it were, what life is. To put it another way, it demonstrates the human desire to step outside the world and see the whole of it clearly, objectively, in a way that makes sense of the totality of being. This is rationally impossible for a thinking individual, living within the world. You can’t step outside yourself and get a good look, let alone step outside the entire world for a more comprehensive view. In a similar way, in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Wittgenstein pointed out, in reference to logical thought as a picture of the world, “2.174 A picture cannot place itself outside its form of representation.” And “3 The logical picture of the facts is thought.” Therefore, thought cannot get outside itself to see and express clearly its own relation to the world. Nevertheless, thought reaches its limit and keeps pushing, speaking nonsense—in Wittgenstein’s sense—in order to express what’s unthinkable and inexpressible. There is something both absurd and yet utterly essential in this endeavor, this craving, and this restless compulsion resides at the core of Wittgenstein’s life work. He spent his life attempting to clarify the limits of reasoning and to show how reasoning—and especially science—isn’t enough, it can only take you so far, and not very far at that, when it comes to understanding how to live a good life, in both the ethical and aesthetic sense.

In his essay on ethics, he says:

I contemplate what Ethics really would have to be if there were . . . a science, this result seems to me quite obvious. It seems to me obvious that nothing we could ever think or say should be the thing. That we cannot write a scientific book, the subject matter of which could be intrinsically sublime and above all other subject matters. I can only describe my feeling by the metaphor, that, if a man could write a book on Ethics which really was a book on Ethics, this book would, with an explosion, destroy all the other books in the world. Our words used as we use them in science, are vessels capable only of containing and conveying meaning and sense, natural meaning and sense. Ethics, if it is anything, is supernatural and our words will only express facts; as a teacup will only hold a teacup full of water . . . <even> if I were to pour out a gallon over it.

One’s first reaction to this is to say that there are, on the contrary, many quite obvious ways to describe ethical behavior, good behavior, a good life. Why is a book on ethics so unthinkable? Karen Armstrong, who studies the commonalities of the world’s religions, reduces the essence of religion to one imperative, The Golden Rule. This would seem to be a way in which one could answer the question about the most important thing in life, or the meaning of life: to not do to others what you wouldn’t want them to do to you. This is for her the heart of all ethical codes. But this advice isn’t a proposition that can be verified; it isn’t a statement of fact that is either accurate or inaccurate. It isn’t an argument that turns a command—love your neighbor as you love yourself—into a propositional truth. It’s still an imperative, or command, and is in a sense supra-natural, not a proposition about facts, not something derived from the world or the sum total of facts about the world. It isn’t something one can derive rationally from what is the case in the world. The goodness of treating others with kindness and love may seem self-evident, but only if you begin with a presupposition of a self-evident absolute good—and reason has no way to express or comprehend this absolute other than to believe that it obtains. It doesn’t exist in the world and reason can only contend with facts in the world. This presupposition of an absolute good may be utterly central to your life, but as a rational postulate it’s a chimera. Absolute goodness can’t be located or described or, really, imagined, let alone verified. For Wittgenstein, the only way to clarify this idea of The Good is to observe how language about it is used in a particular way of life.

All of this carries over into how Karen Armstrong, in A Case for God, explains why religion has become intellectually discredited over the past two centuries and yet is alive and well, in various forms across the globe: because it has been misunderstood as a set of propositions about the world rather than a complex language that “shows forth” a way of life that can embody a distinctly different awareness of human existence, with all the concomitant behavior that embodies it. The key for her, and Wittgenstein—and Tolstoy before him—was the realization that religion (and art for that matter) are ways of life, founded on the desire to align oneself with absolutes that transcend the facts of the world. Only with an assumption of these absolutes do facts have any value whatsoever. Otherwise, the world is a collection of neutral facts, none of which have more value than the others. Wittgenstein says:

I see now that these nonsensical expressions were not nonsensical because I had not yet found the correct expressions, but that their nonsensicality was their very essence. For all I wanted to do with them was just to go beyond the world and that is to say beyond significant language. My whole tendency and, I believe, the tendency of all men who ever tried to write or talk Ethics or Religion was to run against the boundaries of language.

This running against the walls of our cage is perfectly, absolutely hopeless. Ethics so far as it springs from the desire to say something about the ultimate meaning of life, the absolute good, the absolutely valuable, can be no science. What it says does not add to our knowledge in any sense. But it is a document of a tendency in the human mind which I personally cannot help respecting deeply and I would not for my life ridicule it.

2

In this essay on ethics, as should be obvious from the clarity of these quotes, Wittgenstein says fundamental things about both ethics and aesthetics, religion and art, directly and plainly (in a way that’s more conversational than his better-known work which often leads the reader around the insight he wants to evoke, circling it and aiming at it obliquely.) For example, about his intimations of absolute goodness:

I believe the best way of describing it is to say that when I have it, I wonder at the existence of the world. And I am then inclined to use such phrases as ‘how extraordinary that anything should exist’ or ‘how extraordinary that the world should exist.’

And shortly, he adds:

The first thing I have to say is, that the verbal expression which we give to these experiences is nonsense! But it is nonsense to say that I wonder at the existence of the world, because I cannot imagine it not existing.

MORE

September 20th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Screen shot from Bridge

I met a young artist at the Chautauqua Institution in August, Ali Georgescu, through her grandparents, who visit during the lecture season every summer. Having recently earned her degrees at Kenyon and Columbia College Chicago, and still looking for a path out into the world, Ali was working the front desk at one of the galleries. She’s a “lens-based” artist herself, but her work wasn’t on view in the student show at the Fowler-Kellogg Art Center. Having toured that show and then later in the day viewing one of Georgescu’s videos, I was more taken with her work than with anything I saw in the exhibit, except maybe an archival inkjet print, Truth or Consequences, by Furen Dai.

Georgescu is an observant young woman, laconic, skeptical, but personable and quietly intelligent. Her video, Bridge, is a montage of short excerpts from archival video and film. With software she’s constructed a dream sequence that reminded me a little of the deadly video in The Ring except that with the VCR footage in The Ring it’s actually easier to deconstruct what you’re looking at by the end of the movie. (I didn’t get a dreaded phone call, with Bridge, and haven’t yet died after watching it several times.) I’ve been charmed enough to keep going back and trying to make out what I’m seeing and though I haven’t made much headway, I’ve enjoyed it more each time. It seems there are maybe a couple dozen excerpts fused into one surreal narrative: a road rolling under the camera, a knife-thrower using a child as a target, houseflies flickering into view, ocean waves, large fish swaying against one another, a close-up of a woman’s eye—all of it slightly out of focus and most of it washed out, as if the lens were pointed toward a setting sun. Behind the entire video is a tubular white noise, eerie and hollow, affectless. You look at this sequence of imagery as if through a strange, throbbing, square tunnel. In the end, everything is swallowed by that oncoming light. I wanted to see and recognize more of what she was showing me, have something come into focus at last, but nothing ever did, and yet as a result the seven-minute video—for all it’s remote and chilly imagery—felt almost nostalgic and wistful, like the fragmented memories from a child of itinerant parents. It’s haunting and assured and maybe an indication of even more interesting things to come.

September 7th, 2021 by dave dorsey

In 2004, for his MFA thesis at the University of Maryland, Matt Klos painted a series of underground studio spaces. In these White Paintings, he paid homage, in his own idioms, to the work of Antonia Lopez Garcia. He represented various aspects of a drab and artificially lit basement studio. All of these interiors were spare and utilitarian and slightly abandoned-looking. The subtle complexity of their white walls fascinated him, as well as their blank, apophatic humility, the quality of erasing themselves, reflecting maybe just enough light to direct your attention to the muted color of other charmless things in the room: a utility sink or a chalkboard or a skeleton. As Klos put it in his thesis, in this small series of studio scenes, he wanted to evoke “the ethereal beauty inherent in the visible.” That doesn’t seem quite right. Most painters I know have signed up for that mission. It’s more as if, in his work, he wants to create a way of tapping the potential for a pictorial beauty inherent in a place, a beauty that wouldn’t be quite visible anywhere except in the quality of a painting of it. The beauty of a Matt Klos painting lives in the intensity of his gaze, and the insistence of his struggle to make paint retain its character as paint on a particular surface while conveying the life of what he sees. (This seems like a core axiom of the perceptual painters with whom Klos has aligned himself.) Mostly, like Antonia Lopez Garcia, he likes the challenge of representing what wouldn’t instantly be recognized as lovely or appealing. The beauty of his painting rests in the uncompromising passion that drives this assiduous and painstaking attention to what most people might not bother to let their eyes rest on for more than a few seconds.

It would appear Klos hates to come up out of the basement. For a decade and a half, he keeps returning to these underlit spaces, some of them cluttered and crammed with antiquated objects or the tools he relies on. (He does come out of Plato’s cave now and then, though. When he ventures above ground, as he does regularly, his work is quite different, often bright and stunningly expansive even in the confines of very small canvases. His little painting, Belfast Bay, is a marvel in which he creates qualities of scintillant light and a sense of a vast brilliant stretch of water simply through the way he magically scumbles the paint.) His new solo show, Contents of a Cabinet, at Gay Street Gallery is virtually a catalog of the many antiquated things left behind by a previous resident in a basement he adopted as his studio in Maryland more than a decade ago. He paints in a working-class neighborhood near the “recently closed Bethlehem Steel plant in Sparrows Point.” (The most startling word in that artist’s statement is “recently.” How did an American steel plant survive so long?) As he wrote for the first installment of this series of studio paintings at Gay Street in 2017, when he moved into the space more than a decade ago, “Dust and disorganization obscure the objects. Even when the objects are clearly defined their meanings may be lost to our current generation. In an age when so many answers are at our fingertips, I marvel at what seems to be a disconnection with our recent past.”

At the gallery’s website, the paintings aren’t titled, nor are their sizes indicated, though it’s clear from the texture of the surfaces that some are quite small. The larger paintings are the most intriguing. Klos paints the sort of things that look as if they stayed put on their shelves after an estate liquidation and weren’t snatched up by survivors of the owner’s death. He shows an old Sanka can, probably full of nails or bolts, and then something that looks like an improvised vise for squaring a frame, and shelves full of Depression glass and old dishware, a teapot, dolls, candles, a box full of wrench sockets, and an old landline wall telephone. These objects mostly give the impression of physical weight and mass, and they cast harsh shadows. They look stubbornly resistant to current culture, popular style, feng shui, ergonomics, and the virtualization of human experience: in other words, they are immune to everything contemporary, with one eccentrically lovely exception. Somehow, Klos gives us the guts of what appears to be a desktop computer being scavenged, its little green circuit boards (a video card maybe, or a wafer of RAM) glowing like grass in a university quad, lodged into a composition arranged as a wheel of muted, subtle colors: coral, ochre, olive green, blue-grey, and dark apricot. Against this parade of lumpy physicality, there is one painting in the series that looks as if it crashed this party from another dimension. In what almost qualifies as a Diebenkorn vision of a Santa Monica ocean view, Klos shows the viewer two blank turquoise panels, side by side, bisected by a small crease through which you can see vague gray details of what’s hidden behind the panels, a small and vibrant wound around which everything pivots, with a little bleeding sliver of brilliant red near the bottom. A rectangular streak of blue sweeps across the base of the canvas, and along the left border (bringing the viewer back to earth) what appears to be a sheer robe or apron hangs to the left of the panels. It’s a brilliant, luminous study, minimalist, almost non-representational, full of joy, as if all the expansive green and blue of sea and sky and mountains beyond the walls of this work space had flooded into his basement through this one canvas.

What keeps me coming back to look at the paintings in this show is a jumbled interior scene with what appears to be a child’s brilliant painting on paper that has come loose from its anchoring tape and rests askew behind and above a fat red candle resting on a flat surface shared with a couple dolls and a Kleenex tissue cube. In front of these objects is what appears to be the upholstered backrest of an antique, carved hardwood chair. The surface of the wood is conveyed with precision, the cataract glaze of its old glossy finish gone dull and gray, all of the cordovan-colored wood in bad need of being stripped and refinished. The whole composition, like the neo-Diebenkorn canvas, is structured in concentric rectangles shaped by wires and lumber, these elements criss-crossing themselves into a firm grid around the red, unlit candle that looks votive given the fact that it’s sitting just below a crucifix hanging on one of the exposed studs in the upper right corner. The whole image inhabits a sort of tattersall of crosses. Klos includes two paintings of this scene in the show, the other one a quick study of these central objects, including the crucifix. As you absorb these circumstantial indications of spirituality, you look again at the Kleenex tissue and it seems to be floating up like smoke or a ghost or rising like a shrouded figure from its cube. It all offers just enough of a signal of Matt’s faith: it doesn’t overwhelm the painting, but makes itself felt and appreciated and respected as a quiet affirmation of something that seems to be at home among things discarded and overlooked by contemporary culture. It would be interesting for someone to do a study of how current painters tackle the struggles and disciplines of faith, from any tradition, and the parallels to the work of painting itself: the requisite mindfulness, humility, and patience. In my own work, faith is entirely subliminal, a motive for painting without being the overt subject of anything I depict. This may be Matt’s situation as well: painting as a corollary of prayer.

During the Renaissance the question of faith was quite simple: it was the reason for painting anything, the system in which painting made sense. After the advent of modernism, with a few exceptions like Rouault, faith seems to have little place in most painting, especially now, given the West’s intellectual antipathy to Christianity. Even though more than two-thirds of Americans identify as Christian, do painters need to work little samizdat signs, like this basement crucifix, into their images as a code to other spiritually devoted types? Being a Christian can’t be an effective calling card in Chelsea—more a quick way to get ostracized and banished from sophisticated society. Which makes these indications of it just as much a signal of artistic integrity as a predilection for painting things underground.

August 29th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Alice Carpenter, monotype, relief inks on paper, 4″ x 4″

This monotype was selected for the 2021 Butler Midyear, another of the remarkable pieces included in one of the best Midyear exhibitions Butler has assembled in quite a while. I’m dumbfounded by the way Carpenter can convey a dreamlike, timeless, and utterly haunting world, a world that feels both slightly oppressive and yet spacious and expansive, all within the confines of a tiny square of paper.

August 25th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Marc Ross, Make Me That Happy 2, Acrylic, pastel and color pencil

53″x 55″

Another work from Marc Ross won Best in Show at the Butler Midyear exhibition. His exquisitely executed abstractions refer back to Rothko, minimalism and the ghostly, incremental discriminations of Agnes Martin’s bands of faint color, but his work is all his own.

August 21st, 2021 by dave dorsey

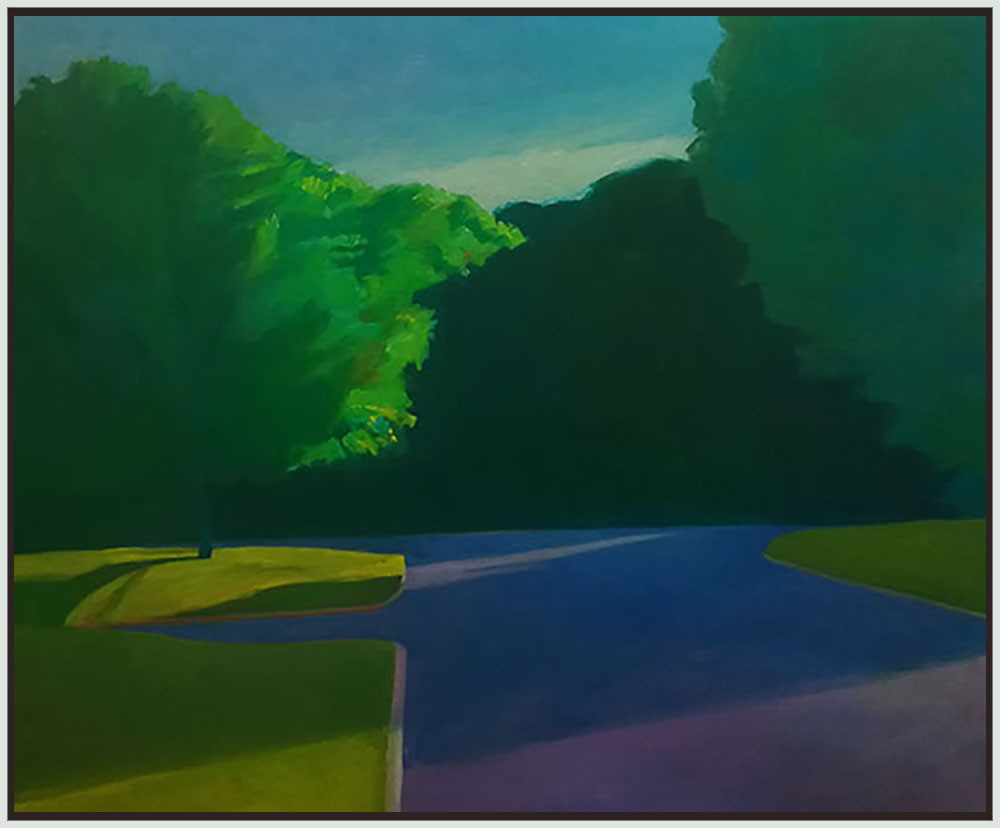

Frederick Fochtman landscape.

Fred Fochtman’s website is so minimal that I was unable to find a title, size or medium for any of the work there, but it’s fairly clear this is a small oil or acrylic. I discovered Fochtman’s work through the two paintings of his in the 2021 Butler Midyear. I went back through the past few years of his painting and quit clicking when I came to this one. It evokes for me what C.S. Lewis talked about in his autobiography: a feeling of joy fused with a sense of the unattainability of lasting happiness in a temporal world. He had this experience as a child when it seemed as if the eye of his soul was able to glimpse the “idea of autumn,” in a Platonic and eternal sense, the isness of autumn. This little painting opens a window on both winter, with the roadside snow, and somehow spring or even early summer in the color of the lake in the distance. Yet the color in the trees along the road look like autumn. My vision of these mixed seasons only heightens the effect this scene has: a deeply familiar mild winter day, the road with shadows reaching across it could be warm from the sun and the wind maybe fragrant with the thawing soil. It’s the perfection of a normally unregarded moment except that you suddenly feel as if everything is exactly as it should be, a gift, if something causes you to actually quit thinking and just notice everything. Easier said than done. The humility that undergirds everything in this painting is what makes it what it is: the simple act of putting paint on canvas in the hope that all of this will be conveyed, as it inexplicably is here. It’s an act performed for no other reason than that a warming winter day on an empty road with a lake too distant to make a difference, and with nothing ordinarily considered worthwhile going on, can be perfection itself. A moment like this of utter insignificance can somehow give you a glimpse of who and what you are, especially if you see it in a little painting like this.

August 17th, 2021 by dave dorsey

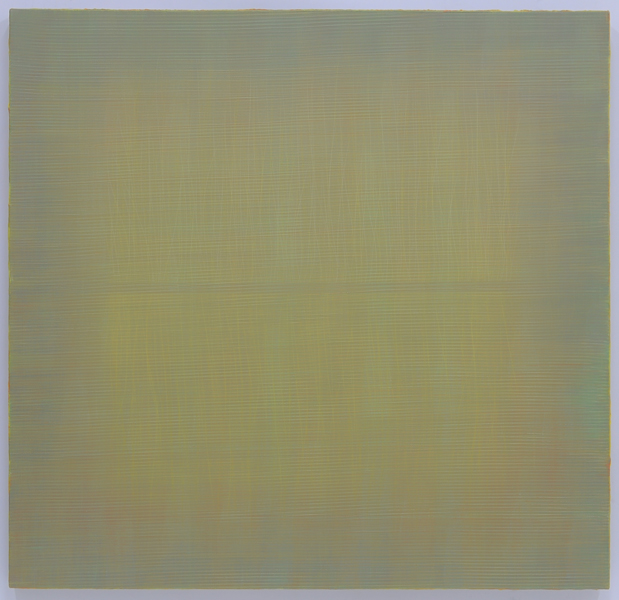

Taffy #3, oil on linen, 46″ x 46″

Taffy #3, which I refer to now as Happiness, is going to be included in Manifest Gallery’s INPA 10. If I were clever and a careerist, with a little sophistry, I might argue that my series of salt-water taffy paintings represent a nostalgic, ironic commentary on a lost period of art. They do remind me of the Sixties, full of hope, full of clarity about America’s primacy in everything, all those paintings filled with confidence in the advance of art history toward new discoveries. It’s true, I’ve been calling them “color field candy” informally for quite a while, because my deepest inspiration for these images comes from the work of painters like Stella, Rothko, Agnes Martin, and Frederick Hammersley. One might be more inclined to suspect my hope is to honor the influence of Wayne Thiebaud, that my real allegiance is to Pop, that I am engaged in a kind of re-interpretation (in a soft, wistful minor key) of what’s happening in Roberto Bernardi’s current hyper-realistic images of hard candy. But, as much as I revere Thiebaud as a serious artist engaged in discovering ways to do things with oil that others haven’t done, the work of other painters of candy is rarely on my mind when I’m making crucial decisions about these paintings. I see these paintings as realistic depictions of what amount to little abstract sculptures.

The choices I make with each painting sound amusingly absurd and trivial: what candy to use, whether and how to unwrap and re-wrap it to my liking, what to do about that squiggly Taffy Town logo printed on the waxed paper when I use that brand of candy (see what I mean?), what lighting to use to on these little chunks of colored sugar, and how to crop and then develop the photograph I take of them, using Lightroom. I began to paint this candy as an offshoot of the jars I started doing a decade ago, where my aim was more abstract: to create a kind of honeycomb grid defined by the shape of the bulk candy poured into a small pasta sauce jar. I would use the slightly irregular grid formed by jelly beans (if you viewed the jar directly from the side) to improvise with the colors in each cell of the grid—in other words, each Chiclet, or jelly bean, or M&M. My struggle was to create an image that was a three-dimensional representation but it also worked as a flat, minimalist pattern where I could completely choose and control the colors in the pattern, mostly by picking the candy. With some smaller candy jar paintings I worked from an image of all-white Tic Tacs and depicted them using whatever arbitrary colors I needed to make the image come alive in a certain way.

With taffy, I’m not thinking in the same way, or if I am, it’s at an ironic remove from any intent to honor the notion of flatness. When I bought a bag of salt water taffy many years ago, I was thinking of getting a larger jar, tumbling the taffy into it and then addressing the patchwork color composition it would create through the shine of the glass and the haze of waxed paper between glass and candy. It’s still an interesting challenge, but it put me off for many years, partly because it was hard to imagine a comparable jar, as wide as it is tall, with threads at the lip for tightening a lid, large enough to contain enough of those twists of taffy to be interesting. A few years ago, I thought again of the taffy and found websites where I could order specific color combinations and began to stock up, filling boxes with the bags that arrived. I finished one, a large, loosely executed image of three pieces of taffy stacked like a cairn. I promptly went back to my more traditional still lifes, concentrating on bowls decorated with Indonesian Ikat patterns. About eighteen months ago I finally returned to the taffy, and I have finished a dozen of various sizes. A dozen means I’m only about halfway through the series, which I intend to propose as a solo exhibit when this suite is mostly complete. It’s taking far longer than I anticipated when I began the project.

The taffy calls out to me primarily with its color, which is where I am haunted by the Sixties: the beautiful tones in the work of Stella, Hammersley, Noland, some of Blinky Palermo, Diebenkorn, Martin, even Bridget Riley, it’s a long list of painters who had an unabashed love of color for its own sake. With taffy, that love is slightly unrequited by the painting. It holds itself back. The evocative hues are partly hidden, bound inside the translucent waxed paper, in shapes and with colors that reflect my yearning for the minimalist simplicity of a Matisse cutout, the vibrance of a Stella protractor painting, and the sometimes quirky shape of a little Hammersley etude with its organic lobes of orange and yellow. Sometimes, the three globes, two on top of the surface, one the reflection of the bottom candy, remind me of Rothko’s landscape format: the sky, the horizon, and the earth. Again, I know this must sound funny, but I hope it’s funny in a self-effacing way: Rothko’s epic, sometimes tragic moods revisited as candy. Yet this love affair with flat minimalist color is ironically (yet with no snarky intellectual commentary intended) given weight and three-dimensional form, as if a color field painting had been melted down, compressed and molded into a nugget the size of a large walnut.

I was intent on numbering these paintings so that their status as variations on a partly rigid format, and their kinship with abstraction made a little more central, but in looking at the ones I’ve done, they evoke a plethora of moods, predicaments, epiphanies, times of day, spiritual states, and even myths. So I’ve gone back and taken away their number and given them a name (to turn a song lyric from the Sixties inside out). So, when I’m done, I’m looking at a little imaginary seed, which, when immersed in the mind of a viewer, I hope will unfold and expand into a vision of flat patterns of color as large as anything, the way memories are big without really having a size. Yet the waxed paper keeps it real, tethered, with forms that echo the heaviness of a clothed human body, fixed but not rooted to its place on my kitchen countertop, near the sink window, where I place the candy to photograph it. It’s earthbound, maybe yearning for flight with those waxed paper wings that would certainly droop in the summer heat as the taffy began to ooze in the sun. But while it’s poised, doing its balancing act, these little hunks of sugar seem full of hope, love, submission, longing, thwarted ambition, and even more defiant feelings, not always definable, the way a certain hour of the morning or a post-midnight walk on a deserted city street seems full of a particular mood, a sense of all human possibilities, without being about much of anything at all.

August 13th, 2021 by dave dorsey

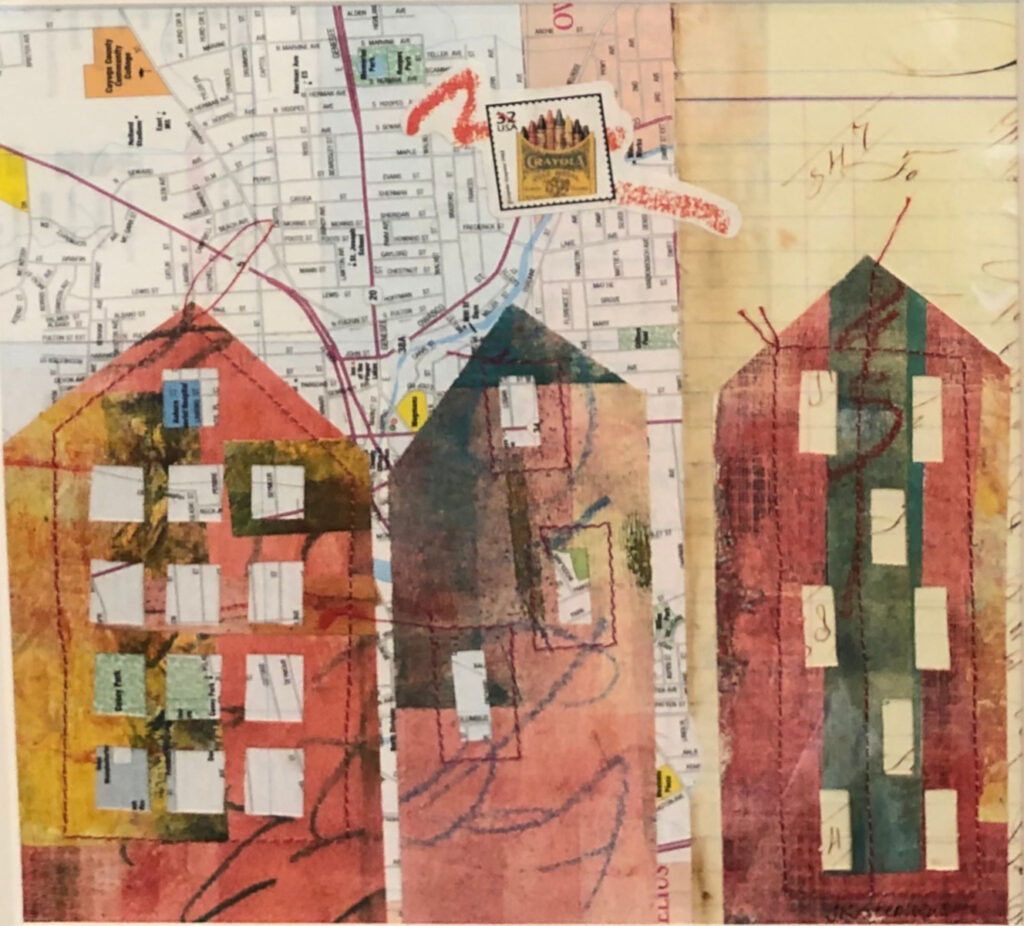

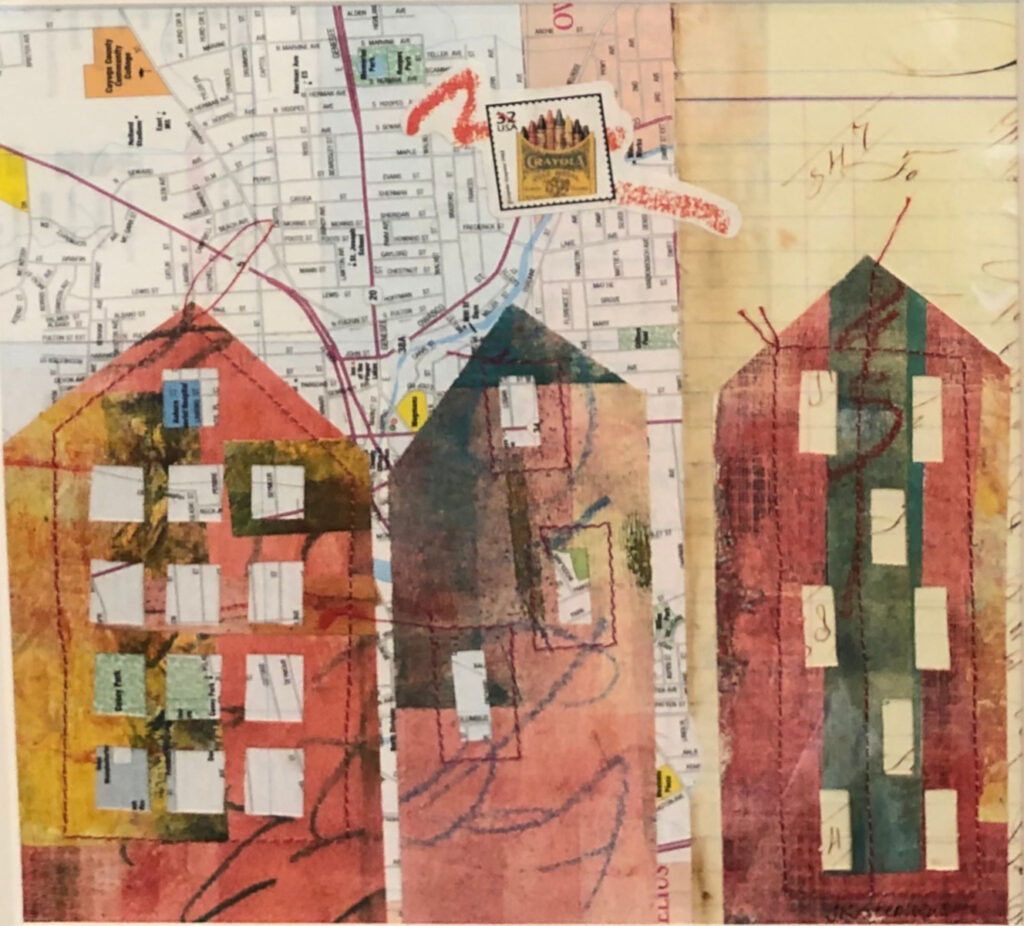

On The Map, Jean Stephens, mixed media collage

The pandemic had some upsides. My son and his family moved from California to live a mile away from us here in Pittsford, N.Y., after they discovered they could keep working in movies and television from thousands of miles away. It’s suddenly the Zoom era, and we couldn’t be happier about it. Jean Stephens, already living here in Western New York, took advantage of her self-imposed isolation to liberate her imagination through the act of simply paying attention to what she was enduring: both her physical confinement and how it launched her imagination into a series of soaring and lyrical new collages.

It’s a major shift in the way she makes art.

She does gelli monoprints and then uses the patterns created on the paper she applies to the acrylic-impregnated gel to carve out the shapes of houses and buildings. These are applied to a substrate of colored patterns Stephens pulls from her medium when applied to textured surfaces—the textures she has discovered in objects from a variety of sources, including a hardware store. Into the mix, she works the curving lines of script from old letters or other printed material. She collects objects wherever she finds them in her travels—stamps, letters, cards, as well as anything that has an interesting surface from which she can pull a pattern, including something as mundane as drywall tape. She uses all of them, picking just the ones that seem to work in juxtaposition with one another to create a little visual song of memory, imagination and yearning. Each image is like a visual poem, and in one, an Irish postage stamp floats in the sky above a house perfectly evoking the thwarted longing for freedom everyone felt last year. Her luminous color harmonies are marvelous.

Her work is on view at the Stephen Merritt Gallery, Merritt’s stand-alone studio situated behind his home on a densely wooded hillside north of Rochester. He converts his studio into a gallery for occasional shows. This one features, in addition to Stephens, fascinating new drawings from her husband Bill Stephens, Loraine Cooley’s beautiful jewelry and Dick Westfall’s amazing woodwork.

Stephen Merritt learned how to create his assiduously crafted terra cotta vessels in the late 1960s and early 1970s, studying in Japan under the guidance of Ishikawa Seiho and Inoue Manji. He has been deepening his understanding of the techniques he acquired over the past five decades. While the vessel is still moist, he brushes it with a variety of clay slips—watery solutions of different kinds of clay. His surfaces have a lustrous semi-gloss, or even matte, finish that suggests layers of subdued color, in the way living tissue reflects from various depths to create complex flesh tones. Each vessel seems to vibrate differently to the eye, but all of them emanate a balanced, meditative tone, a kind of spiritual energy that’s contained, withheld, but alive. His work is in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, The Burchfield-Penny Museum, the Memorial Art Gallery and the Everson Museum.

August 10th, 2021 by dave dorsey

The Blue Side, Patrick Lee

One of Lee’s interiors is on view at the 2021 Butler Midyear exhibition.

August 6th, 2021 by dave dorsey

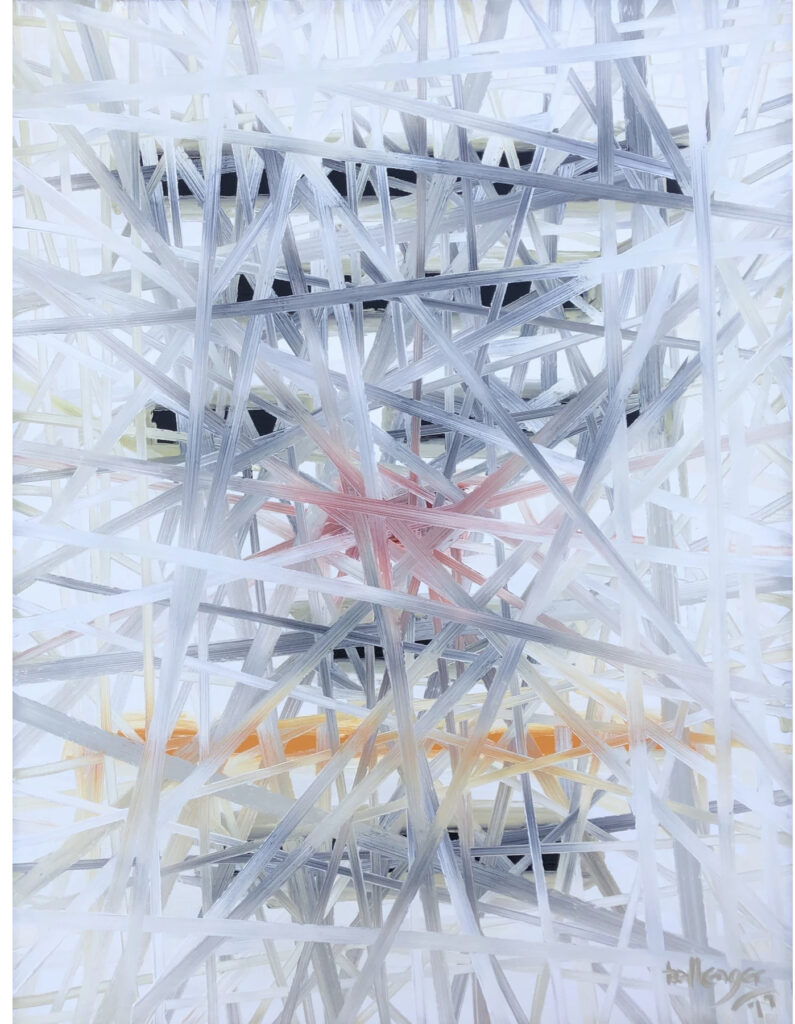

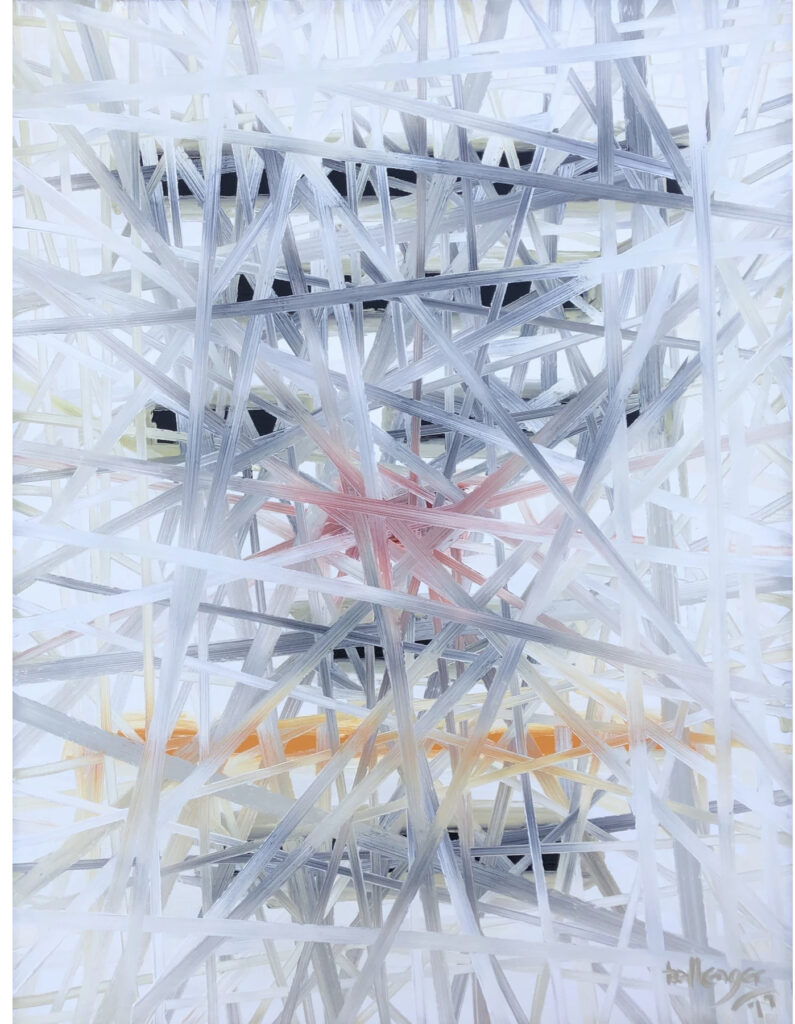

Sampler, Brian Ballenger, oil on canvas, 26″ x 34″

The question of how Ballenger creates these abstractions has puzzled me since I saw another of his paintings in the 2021 Butler Midyear. Here, the surface appears to be wet-on-wet bands of paint, created with uniform passes of a brush across the wet surface, guided by a straight edge tool. The way the bands seem woven together must be an effect of the order in which he applies them, and the complexity and number of the swipes across the canvas give the impression of wicker’s in-and-out network. He must work quickly, keeping the paint wet from start to finish. In this particular painting it looks as if he began with horizontal marks of black, orange and a kind of faint damask surrounded by white negative space, and then worked the completely coated surface with his rigid criss-crossing marks. The sense of three-dimensional depth is marvelous, a beautiful affront to Clement Greenberg, more than half a century since his celebration of flatness both supercharged and narrowed the way America thought about art. Obviously, we’ve recovered.

August 2nd, 2021 by dave dorsey

The Enigma of a Street, William Reed Simon, oil on canvas, 22″ x 27″

This is the first of several posts featuring the work of artists chosen for the 2021 Butler Midyear exhibition at the Butler Institute of American Art.

Insalaco has been working for years on a series of paintings showing city traffic at night, almost an extreme reduction of his usually dark motifs into two-tone compositions that either look like a procession of ghostly headlights or sinuous lines of stars against the black ground of the urban night. In Night and Light, the title emphasizes the stark juxtaposition of blindingly bright light against almost featureless darkness. Yet this potentially bleak darkness comes across as familiar and alive: two figures, perfectly rendered in the half-light, watch the passing cars and make the viewer feel like another pedestrian enjoying the night’s energy. It’s as ordinary as a remembrance of a late walk to your room in New York City, but also suggestive of the anonymity of city life in a spiritually-isolated age.

Insalaco has been working for years on a series of paintings showing city traffic at night, almost an extreme reduction of his usually dark motifs into two-tone compositions that either look like a procession of ghostly headlights or sinuous lines of stars against the black ground of the urban night. In Night and Light, the title emphasizes the stark juxtaposition of blindingly bright light against almost featureless darkness. Yet this potentially bleak darkness comes across as familiar and alive: two figures, perfectly rendered in the half-light, watch the passing cars and make the viewer feel like another pedestrian enjoying the night’s energy. It’s as ordinary as a remembrance of a late walk to your room in New York City, but also suggestive of the anonymity of city life in a spiritually-isolated age. conveys the rich warm color of a setting sun over a strip of land and sea, all of it minimally indicated, yet rich with carefully applied color and brushwork that somehow passes for cloud formations but also looks expressionist and gestural. She has been making art for many decades, and now late in her life is still innovating as a quietly original and masterful print-maker whose feel for color has always been superlative.

conveys the rich warm color of a setting sun over a strip of land and sea, all of it minimally indicated, yet rich with carefully applied color and brushwork that somehow passes for cloud formations but also looks expressionist and gestural. She has been making art for many decades, and now late in her life is still innovating as a quietly original and masterful print-maker whose feel for color has always been superlative. author of each book then a unique work of art to visualize the book’s content in the spaces where borrowers would normally sign their names. The drawings are funny, clever, touching, and sometimes mysterious. All of them are either lively, lovely, or both. One of her contributions to the show is a copy of the

author of each book then a unique work of art to visualize the book’s content in the spaces where borrowers would normally sign their names. The drawings are funny, clever, touching, and sometimes mysterious. All of them are either lively, lovely, or both. One of her contributions to the show is a copy of the  thought, “This is either about marriage or politics.” Then I saw the title in Jim’s price list and laughed. It is a funny painting—it shows what appears to be a white rooster running toward the left with a small group of black roosters running toward the right, the group clearly running away from the lone rooster and vice versa—as a metaphor of cluelessness of our contemporary political luminaries. But it’s a haunting image, and the faint light that falls on the agitated fowl bathes them in a sad kind of wisdom, as if this flight makes visible the universal human desire to flee the truth in a fading light that makes this possible and only fades faster because of it. The image transcends its

thought, “This is either about marriage or politics.” Then I saw the title in Jim’s price list and laughed. It is a funny painting—it shows what appears to be a white rooster running toward the left with a small group of black roosters running toward the right, the group clearly running away from the lone rooster and vice versa—as a metaphor of cluelessness of our contemporary political luminaries. But it’s a haunting image, and the faint light that falls on the agitated fowl bathes them in a sad kind of wisdom, as if this flight makes visible the universal human desire to flee the truth in a fading light that makes this possible and only fades faster because of it. The image transcends its