Fransioli

Currently on view at Hirschl & Adler:

Thomas Fransioli (1906-1997)

Copley Square, Boston, 1959-61

Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in.

the painting life

Currently on view at Hirschl & Adler:

Thomas Fransioli (1906-1997)

Copley Square, Boston, 1959-61

Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in.

During the recent afternoon I spent with Tom Insalaco at his home studio, I saw some of the amazing work he’s done over the past several decades. It’s a measure of his humility and generosity that he spent less time showing me his own work than he invested in introducing me to—or reminding me of—great work from other contemporary realists.

When he could have been pulling big paintings out of storage for me to photograph, instead he handed me a catalog of work by Richard Maury, a slim set of wonderfully printed plates from a show more than a decade ago at Forum. He pulled it out the the midst of hundreds of books Tom keeps on his shelves, including the entire catalog raissone of John Singer Sargent. Tom has spent a lot of time in Italy and ran into Maury there once:

“He’s wonderful. In one of his paintings, you can sense the terra cotta under the glaze on a little ceramic jar. You can sense the depth of the glaze. We found his house in Florence and who comes walking out the door but his wife. I was in Florence and was walking to a church to look at Masaccio, and we stopped a guy with red hair, and he said something and I said something . . . and it was Richard Maury. I didn’t realize it at the time. He was speaking in Italian, but he knew the ins and outs of English. He really had bright red hair back then.”

We talked for several hours, and Tom showed me dozens of drawings from a collection of the ones he has done every morning, without fail, on sheets of rag paper he has prepared by tinting them with oil—“It has to be rag paper.” Working from the overall middle tone he lays down, he creates portraits of people from photographs in the Renaissance manner, adding darker tones the usual way and then highlighting with white. (I recently skimmed through a catalog from the fantastic Durer show of drawings and prints at the National Gallery of Art in 2013 and was surprised by how intensely white Durer’s work was in those highlighted areas.) What was impressive was the size of that sheaf of sketches—Tom draws every morning, first thing, before doing anything else. Up, out of bed, he begins drawing immediately. When he’s done, he gets a little breakfast and then it’s on to his easel at the front of the house.

I’m guessing that Tom is in his mid-70s now, but hasn’t slowed down at all. He has a better memory than I do, and recalls things I’ve told him in passing about my wife and brother and parents, and also comes up with names of specific paintings by artists who don’t even ring a bell with me. He has no patience with contemporary art, and his recent visit to the new Whitney nearly enraged him when he saw the floor of one gallery space covered with a foot of mud—a recent installation.

“I don’t know if you’ve been to the new Whitney. Last time I was in there I screamed. I said why don’t you have the art, instead of this? There was a room full of mud, twelve inches deep. They probably thought they needed to call the police. It was chicken shit. They have so many great paintings. Edward Hopper’s Sunday Morning. Jack Levine’s Feast of Pure Reason. Why don’t they hang that?”

I timidly suggested that the Stella retrospective there now might help ameliorate the effect of the mud, and he allowed that this might be the case, but still . . .

It’s refreshing to talk with someone so candid and unguarded about how he feels when confronted with much of what’s happened to visual art. What I don’t understand, I told him, is why a curator in Western New York isn’t putting together a retrospective of Tom’s work, which reached epic proportions in a trilogy of paintings he did to commemorate the death of his brother a couple decades ago—he was a Buffalo police officer and was murdered by a participant in a domestic fight. One moment his brother was walking up to the door of the house; a few seconds later, he was dead, shot by the man he had come to restrain. Those paintings are monumental; but Insalaco has been building on that work ever since, drawing mostly from Renaissance precursors for his methods, with a bit of Dali tossed in. He was told a year ago or so that he has been invited to exhibit more often in the Memorial Art Gallery’s Finger Lakes Exhibitions than any other artist in Western New York—it’s the most prestigious juried exhibition open to all artists this side of Albany. So why isn’t someone putting together a definitive survey of what Tom has done throughout his career? He wasn’t even included in the most recent Finger Lakes. It would be a wonderful exhibit.

For a guy, c’est moi, who thinks street photography reigns supreme when it comes to cameras, this photography from Ben Thomas is hard not to love in a completely different way. Tilt-shift images are impossible to resist–you’re a child again, the world your playhouse–yet in his Chroma series, the way he transforms images into flat, hard-edged abstractions, with such a limited range of color, is just as satisfying, even if you want him to free it up a little. They’re like pages coloring books for photo-realists.

It’s more expensive, and it takes longer, to fly to Cincinnati than to L.A., and the drive requires an entire work day–just one way–so it’s almost more inaccessible than most cities in the country for someone who lives in Rochester. But at least Jason Franz sends shots of the shows to his participants–and in these you can see my jar full of safety pins among some elegant company at Monolithic, one of the exhibits at Manifest right now.

From Gabriel Liston’s site with the comment: “People live in old boats anchored in the water here between the BNSF bridge and the St Johns.” The modulation of the tones to capture the light is fantastic–it’s the look of a typical winter day here in Rochester, though this one is from Oregon.

From Forty Years of Painting, the catalog for a great Gerhard Richter retrospective I saw in 2002 at the Museum of Modern Art, some thoughts on when he was an obscure and struggling artist. In the interview, he stresses how his aims, in representational work, are classical. It’s a tremendously honest discussion: “I wanted to be seen.” When a friend of mine saw his work recently he said, “I think he’s the greatest painter alive.” Mission accomplished, Gerhard. My interest in Richter is that his work found a place in art history mostly by simply being incredibly good, but also by finding his own way to paint, on his own, without concerning himself with the notion of “progress” or “movements” in art. His sense of alienation from the art of the 60s and 70s makes him a forerunner for everyone now who has to see art as a uniquely individual pursuit, redefining what’s “new” in a completely individual way. You can’t return to the past, but to employ techniques and methods from the past doesn’t require you to be ironic about them. I love the term “tin art” Richter uses. And yet apparently he was pals with Blinky Palermo and “Bob” Ryman, who would seem to be in the minimalist club, so his work is a natural affirmation of what he most values rather than a reaction against other work. He’s candid about his vulnerability in the 60s: “He was a real artist. Not like me.” The interviewer tries to pin down whether Richter is being ironic in his embrace of tradition, whether Richter is really just doing a postmodernist dance, undermining culture, and so on, but Richter answers like a politician about the “absence of the father.” Say what? It’s amusing; yes, the loss of authority, the loss of “the father,” I get it, but he’s still wriggling away from the question.The century as a whole was problematic for him, not to mention the current century, and it’s clear how his feelings are anchored, even though in his abstracts he certainly found a way to embrace modernism. The interviewer manages to fuse modernism and postmodernism into this one sentence as the 20th century club Richter didn’t want to join (his abstracts weren’t under discussion) and Richter agrees he didn’t want to be a part of it:

Your evocation of the classical was basically a response to the whole mood of the late 1960s, early 1970s, where the general rules were: Away with the old; Everything must be new; and Everything must be a cultural critique.

Yes. Exactly.

But that interpretation differs from what many people seem to think the work is about.

Oh really!

Some critics seem to regard the 48 Portraits as an empty, almost stamp-like array of cultural icons. Why do you think it has had strong response?

If it was only postage stamps it wouldn’t be as elaborate, and there wouldn’t be as much trouble. It is too big and there is too much presence and always people wonder what it is about. Women are angry because there are no women. It keeps upsetting people again and again. People are always upset when confronted with something traditional and conservative, and therefore they don’t want it. You’re not allowed to do that; it is not considered to be part of our time. It’s over, reactionary.

Some critics explain it to themselves–make it okay to like–by arguing that it’s an exercise in rhetoric, the rhetoric of a certain kind of representation of culture that questions or nullifies that culture’s authority.

And as I mentioned, you also have the psychological or subjective timeliness of the father problem. This affects all of society. I am not talking about myself because MORE

I’m finally back on a regular painting schedule, and it’s surprising how it puts me in a better mood—helped along by a few other changes in my life. Maybe this makes it odd that I’m thinking hard about taking a year off from exhibiting (while continuing to contribute to local group shows at Oxford Gallery) in order to take all considerations out of the act of painting other than the quality of what I’m doing, based on my own response to it. It’s difficult to resist the sense that I need to refine what I do into something that will either be exhibited or will sell, or both, as a way of validating my work. It’s a little silly to be consciously trying to eliminate these considerations, at this point in my life, since I didn’t give them any thought at all for most the years I’ve been painting—when I did it as a solitary pursuit. In other words, it doesn’t take much effort to quit worrying about a “career” because that’s never been the motivation. Imagine Cezanne or Van Gogh scanning their CVs with a worried look. Being able to both eat and paint is the goal. Whatever creativity is, you’ll kill it by putting a harness around its neck. Once you start showing and selling, as I’ve been doing for seven or eight years now, those activities become a reflexive consideration—you ask, will this be anything someone will want to show or buy? In theory, I don’t think that’s wrong; in fact just the opposite. With Dave Hickey, I agree that making art people want to own ought to be a central consideration, not because it makes sense economically, but because it means an artist is trying to connect to others in a way they’ll welcome. When you speak, you hope someone is listening, otherwise, you’re . . . well . . . you’re a blogger, right? But I’m putting that aside for now. If I give myself a hiatus from questions of selling and showing, I might be able to feel free to fail in an attempt to get better results while painting in ways I ordinarily don’t give myself permission to do. (Do I contradict myself? Very well . . .)

I’m finally back on a regular painting schedule, and it’s surprising how it puts me in a better mood—helped along by a few other changes in my life. Maybe this makes it odd that I’m thinking hard about taking a year off from exhibiting (while continuing to contribute to local group shows at Oxford Gallery) in order to take all considerations out of the act of painting other than the quality of what I’m doing, based on my own response to it. It’s difficult to resist the sense that I need to refine what I do into something that will either be exhibited or will sell, or both, as a way of validating my work. It’s a little silly to be consciously trying to eliminate these considerations, at this point in my life, since I didn’t give them any thought at all for most the years I’ve been painting—when I did it as a solitary pursuit. In other words, it doesn’t take much effort to quit worrying about a “career” because that’s never been the motivation. Imagine Cezanne or Van Gogh scanning their CVs with a worried look. Being able to both eat and paint is the goal. Whatever creativity is, you’ll kill it by putting a harness around its neck. Once you start showing and selling, as I’ve been doing for seven or eight years now, those activities become a reflexive consideration—you ask, will this be anything someone will want to show or buy? In theory, I don’t think that’s wrong; in fact just the opposite. With Dave Hickey, I agree that making art people want to own ought to be a central consideration, not because it makes sense economically, but because it means an artist is trying to connect to others in a way they’ll welcome. When you speak, you hope someone is listening, otherwise, you’re . . . well . . . you’re a blogger, right? But I’m putting that aside for now. If I give myself a hiatus from questions of selling and showing, I might be able to feel free to fail in an attempt to get better results while painting in ways I ordinarily don’t give myself permission to do. (Do I contradict myself? Very well . . .)

So, in this frame of mind, I’m finishing a small, modest still life of a bowl, using methods I’ve been trying for the past year. It’s the first of a series of small ornamented bowls I’m going to paint between now and the end of the year. In this one, as in the last few I’ve done, I’m being completely transparent about my use of photography. I depict one or two commonplace things as the focal point of the image and use a shallow depth-of-field to intentionally create blurred backgrounds. What I’m building is a series of still lifes that show objects in ordinary, everyday surroundings—not simply a wall or undifferentiated space—without rendering the background as precisely as the foreground. In other words, photo-realism, but not hyper-realism. The way I’m painting these backgrounds ranges from slightly blurred but recognizable to extremely out-of-focus scenes that dissolve into softly abstract geometry. It creates a sense of depth in a way some would consider too easy, probably, because it relies on how our eyes have been conditioned to recognize the way a lens alters the view, giving distant things a gauzy aura. I suspect what I’m doing would be dismissed these days by those attuned to what’s currently respected and what isn’t—photo-realism may be commercially viable, but I don’t have the sense that it’s in critical or academic favor right now. Will that last? Probably not. Do I care? No. Maybe a little (see above on Dave Hickey). But that’s precisely what I want to take out of the picture with my hiatus from thinking about sales and shows. With the way I’m working right now, I’m able to achieve pure areas of color that just wouldn’t have the same character if I were to render everything in the image with the same level of painstaking, realistic detail. So far, I like the results. I also like how this approach is encouraging me to find the most efficient way to apply color without losing a sense of clarity and immediacy in the image, despite the lack of detail in most areas. It’s a way of painting where I feel as if I’m using the simplest possible means to get the results I like, focusing on flat areas of color, putting one simple area of color next to another, as Hawthorne said, when he talked about “spots” of color.

None of this has anything to do with adhering to a theory, or some “better” way of painting, but is the result of paying attention to how the act of painting feels as I’m doing it, and whether or not I want to keep looking at the results when I’ve made a mark. It’s a way of savoring the tactile quality of the paint, so that I’m able to spread it in thicker layers and move it around in a way that actually, to me, feels like slicing into a cake—it’s full of that kind of anticipation. I’m sure it’s how Braque felt every time he touched his canvas with his brush. If you’re a painter, you’ll know what I’m talking about: the scale tips toward the paint and the pure color you put down, and the quality of both, while the illusion you create follows along behind, seeming to be summoned up almost as an afterthought of fitting all those shapes of color together in just the right way. I’m also finding myself achieving things with very small areas and gradations of color that undoubtedly nobody else will even notice. I do, though. Someone else, looking at one of these finished paintings might say, “I don’t get it. What’s so different about it?” And there you go: that’s exactly what I was talking about earlier, just painting with only my own eye and heart and hand as a guide, for better or worse, regardless of whether anyone notices what I’m achieving.

I’m happy to have a painting included in Monolithic, one of the current shows at Manifest in Cincinnati. It’s Cutting Loose, Breaking Free, a large oil of diaper pins clustered in my favorite jar, which I’ve used many times, for other paintings like it. Here’s the commentary on the show from the Manifest website:

Sometimes a particular work of art has a way of making us aware of our own physicality, helping us feel our bodies by giving us new perspective on our relationship to things around us. In MONOLITHIC, Manifest presents artworks from around the world that engage our sense of physical, intellectual, and emotional scale.

For this exhibit 82 artists from 26 states and 4 countries submitted 240 works for consideration. Fifteen works by the following 14 artists from 12 states and Canada were selected for presentation in the gallery and the Manifest Exhibition Annual publication.

In two sittings I finished Michel Houellebecq’s latest novel, Submission, a mordant vision of an Islamic future for Europe though the eyes of a man in a state of hedonistic despair. I couldn’t put it down. To call it dystopian is to misunderstand its paradoxes; it simply works out the logic of where things might lead given current events in the Middle East and Europe, speeding up the timeline for Western culture’s surrender to a new order, with a whimper rather than a bang (there’s plenty of the other sort of banging on both sides of the velvet revolution here). The book’s central paradox is that Islam wins, which is both the bad news and the good news, depending on what page you’re on, and how wedded you are to the Western notion of equality. For the author, it seems secular culture built around self-fulfillment has exhausted itself. Houellebecq has been vilified for calling Islam “the stupidest religion” and yet the picture of the society that would follow from this cultural revolution, via a vote runoff, is actually depicted as a supple and peaceful correction to Europe’s socio-economic woes. He doesn’t find it repellent at all. It’s clear that Islam has allure for his main character who seems like an avatar for the book’s author.

For someone who has claimed to be an agnostic, who has said science is the only arbiter of truth, he conveys impotent spiritual yearning in a convincing and sad way. (Recent interviews indicate his views on religion have shifted, or have simply become clear, depending on how you interpret his remarks.) It’s a brilliant book and it made me laugh out loud, and yet it isn’t a satire. Through the mouth of the man who heads the new Islamic Sorbonne in the novel, Houellebecq downshifts into beautiful prose, which comes out of nowhere (given the tone of the rest of the novel), when the subject comes to Muslim worship:

For Islam, though, the divine creation is perfect, it’s an absolute masterpiece. What is the Koran, really, but one long mystical poem of praise? Of praise for the Creator, and of submission to his laws. In general, I don’t think it’s a good idea to learn about Islam by reading the Koran, unless of course you take the trouble to learn Arabic and read the original text. What I tell people to do instead is listen to the suras and read aloud, and repeat them, so you can feel their breath and their force. In any case, Islam is the only religion where it’s forbidden to use any translations in the liturgy, because the Koran is made up entirely of rhythms, rhymes, refrains, assonance. It starts with the idea, the basic idea of all poetry, that sound and sense can be made one, and so can speak the world.

Though he puts those lines into the mouth of a recent convert, he is deeply drawn toward this vision of an Islamic future. (The author at first tried to build the book around a conversion to Catholicism, but wasn’t happy with the results.) To put it mildly, the world he depicts would be a sharp U-turn from the path we’ve been on since the Enlightenment. It’s impossible to imagine Western women peacefully retreating from the workforce as they do here–or putting up with polygamy. It’s also possible to imagine many who would welcome a permanent vacation from the workforce. Houellebecq seems secretly drawn to Islam and feels a nostalgia for the retrograde social order it might bring. You might say he writes about it the way Milton once wrote about Satan, knowing the ostensible enemy is the most interesting character on the page, and maybe the real hero. He’s drawn to what he understands would be a sharp abridgement of all the freedoms that have made his career possible. Islam may loom like a conquering power here, but it would hardly be a despotic rule if the Islamic moderates from this novel took over. Their power grab proceeds through attraction, not force. This isn’t ISIS. The book doesn’t mock anything but the decadence of its central character, as a stand-in for the West’s decline.

Here’s a blast from the past from The Paris Review:

INTERVIEWER

But what stops you from succumbing to what you have said is the greatest danger for you, which is sulking in a corner while repeating over and over that everything sucks?

HOUELLEBECQ

For the moment my desire to be loved is enough to spur me to action. I want to be loved despite my faults. It isn’t exactly true that I’m a provocateur. A real provocateur is someone who says things he doesn’t think, just to shock. I try to say what I think. And when I sense that what I think is going to cause displeasure, I rush to say it with real enthusiasm. And deep down, I want to be loved despite that.

. . .

It may surprise you, but I am convinced that I am part of the great family of the Romantics.

INTERVIEWER

You’re aware that may be surprising?

HOUELLEBECQ

Yes, but society has evolved, a Romantic is not the same thing that it used to be. Not long ago, I read de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America. I am certain that if you took, on the one hand, an old-order Romantic and, on the other hand, what de Tocqueville predicts will happen to literature with the development of democracy—taking the common man as its subject, having a strong interest in the future, using more realist vocabulary—you would get me.

INTERVIEWER

What is your definition of a Romantic?

HOUELLEBECQ

It’s someone who believes in unlimited happiness, which is eternal and possible right away. Belief in love. Also belief in the soul, which is strangely persistent in me, even though I never stop saying the opposite.

INTERVIEWER

You believe in unlimited, eternal happiness?

HOUELLEBECQ

Yes. And I’m not just saying that to be a provocateur.

I spent the afternoon talking with Tom Insalaco on Monday, at his home/studio in Canandaigua. It’s a home built in 1882 and now packed with several decades of work. He paints in what would have been the living room and stores his materials and finished paintings elsewhere on the first floor, including the original kitchen, and he lives upstairs, where he built a room that triples as a fully functional kitchen, a library and a media center. I want to write up the conversation we had but until then, I’m offering the large painting from 1987 that hangs on the landing at the top of his stairs. It’s around five feet square, and is paired with another brightly lit outdoor scene, at least as large, of several tourists standing beside Niagara Falls in full sun. The two paintings are so different–in color and light–from much of what he’s done since then that, when I saw them, I wanted to pull up a chair and study the work for a lot longer than I had time to do. This one captures a moment on a day his then-girlfriend moved into his place as they unpacked her stuff, a frozen cascade of clothing on which floats the dust lid from an old turntable, with the leaves of a big philodendron jutting into the scene, and a little ripple of a woven reed rug in the lower left. You can’t see it well from the iPhone shot, but there’s a taupe pair of narrow-wale corduroys, which became popular in the 70s, folded and sitting in a prominent spot in front of the chair bearing the turntable lid. The way Tom rendered the velvety shine is amazing, each cord distinct and visible. Tom’s artistic idols are Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Sargent, but he loves the photo-realists, and it’s never been more apparent than in this and its companion painting on that second floor landing.

I’ve been reading above my pay grade, as it were, for the past couple weeks, delving once again into On Certainty, by Ludwig Wittgenstein. I minored in philosophy at the University of Rochester, and as a senior I took a graduate seminar mostly to study The Blue and Brown Books, and Philosophical Investigations. When I say “seminar”, I mean that I, and two grad students, met for several hours every week in the office of a tall Afro-American professor who packed tobacco into his pipe and inhaled the smoke (as he would have with a cigarette) for the duration of our conversation. He didn’t lecture us, but played Socrates, as Ludwig often did, too, as we thought our way forward. I was often baffled, if not completely lost, but not always. He was kind, and he never disparaged my beginner’s efforts.

I came out of it knowing what is commonly known about Wittgenstein: that he believed the cure for his philosophical obsessions was to see as clearly as possible how language was fooling him into asking questions, or coming up with theories, that were essentially pointless. Philosophy was a cure for philosophy. (Yet he kept doing it. Continuing to ask a question with no answers somehow matters.) This encouraged me because of my own history, at that point, of asking philosophical questions that had no answer, at least not the way ordinary questions have an answer, embedded in a sensible pattern of behavior, a “way of life.” My reading in that class supported something I’d come to see, through reading Kierkegaard MORE

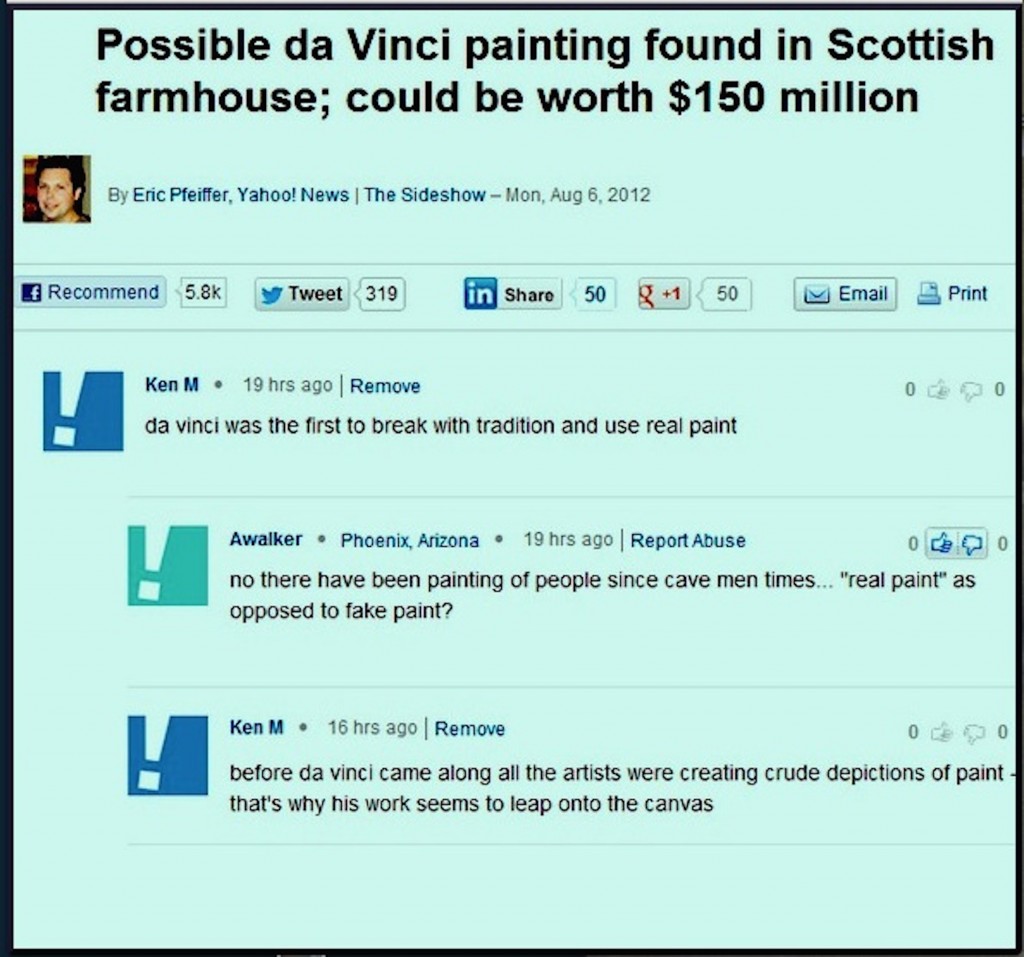

From Gizmodo, here’s a brief salute to Ken M, the world’s most famous and funniest troll, who shares a sample of his incisive views on the art of painting above:

From Gizmodo, here’s a brief salute to Ken M, the world’s most famous and funniest troll, who shares a sample of his incisive views on the art of painting above:

Ken M has achieved what few trolls can dare to dream of. He has his own dedicated subreddit, with 58k subscribers, /r/KenM. The subreddit’s been around for years, just like Ken M, who has collected a following for his deft acts of trolling as the world’s least-informed commenter. His official Facebook page, which lists him as a “professional dirtpig,” has 20k Likes, and he is also onTwitter and Tumblr. His notoriety was such that College Humor paid him to run a column, The Troll, which made him, in truth, a professional dirtpig.

In comments, Ken M comes across as your ornery, befuddled grandfather–that’s what his social media avatars, which depict old men, suggest–but read on and you’ll find his tongue planted firmly in cheek. Ken M’s greatness derives from his subtle trolling method, which is never crude or combative. His apparent cluelessness infuriates others, who don’t seem to get that the joke is on them.

Through it all, Ken M remains blissfully confused. He never breaks form.

Here’s another: