Archive Page 21

May 2nd, 2016 by dave dorsey

Simone Weil

Two quotes from Gravity and Grace, one specifically about art, the other not, but just as applicable to the making of art:

It is an act of cowardice to seek from (or to wish to give) the people we love any other consolation than that which works of art give us. These help us through the mere fact that they exist. To love and to be loved only serves mutually to render this existence more concrete, more constantly present to the mind.

With all things, it is always what comes to us from outside, freely and by surprise as a gift, without our having sought it, that brings us pure joy. In the same way real good can only come from outside ourselves, never from our own effort. We cannot under any circumstances manufacture something which is better than ourselves. Thus effort stretched towards goodness cannot reach its goal; it is after long, fruitless effort which ends in despair, when we no longer expect anything, that, from outside ourselves, the gift comes as a marvelous surprise.

April 26th, 2016 by dave dorsey

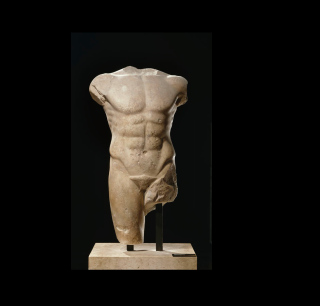

Susie MacMurray’s Medusa, at the opening Thursday

I’m rarely captivated by art outside of painting, which means I usually cherry-pick my way through a tour of New York City shows. A few memorable exceptions would be Terrence Koh’s kneeling crawl around a cone of salt a few years ago at Mary Boone, and the spectacle of Kara Walker’s Sugar Baby. More powerfully than either of those, Susie MacMurray’s work won me over immediately in her 2013 show at Danese Corey. Her work’s metaphoric power seems secondary to its formal originality. It’s conceptually anchored but its impact doesn’t depend on the meaning you extract from it. Most of her work looks unstrained and almost natural. In her current show at Danese Corey, Hinterland, what would have caused injury, in its original form, has been disarmed, and, in turn, is disarming, drawing you toward it rather than pushing you away, as it was originally meant to do: snakes, sniper shells, barbed wire, all become alluring, if only as objects of curiosity, but nearly as often because they’ve become beautiful in the new context she gives them. Her craving for simplicity and unity gives her innovative forms the feel of fresh archetypes, metaphors that attract interpretations rather than assert or contain a fixed meaning. Mythology has that quality, and she echoes a couple Greek tales in this show: Pandora and Medusa.

Medusa was a celibate disciple in the temple of Athena, but was lured into Poseidon’s bed and then punished for her infidelity, given a hairdo of serpents that petrified MORE

April 19th, 2016 by dave dorsey

A computer-generated, 3-D printed, Rembrandt

A short video at thenextrembrandt shows you how researchers created a very convincing forgery, a “new Rembrandt”, using advanced software and data mining to guide a 3-D printer that actually creates a topography of peaks and valleys in the print’s surface to imitate layering of paint. If an artist’s style can effectively be impersonated by artificial intelligence, does that mean a perfect, computer-generated art forgery could essentially convey everything an actual Rembrandt would? In other words, if if passed some kind of critical equivalent of the Turing test by fooling an authenticator and essentially creating a work of art indistinguishable from those of the artist being impersonated–is it virtually the same as an original Rembrandt? If it were possible to generate new works of art this way in the style of your favorite artist, what would happen to the value of the holdings among those who crave art the way the Hunt brothers craved silver? Nothing, probably. The original would still be what it is. I wouldn’t mind having an exact duplicate of my favorite Braque or Matisse or Van Gogh, down to the physical texture of the paint on the surface, for whatever one of these would cost. In this case, it’s still ink, paint-based or not. How long before they can build one of these using actual paint? Artificial intelligence marches on, for better or worse.

April 13th, 2016 by dave dorsey

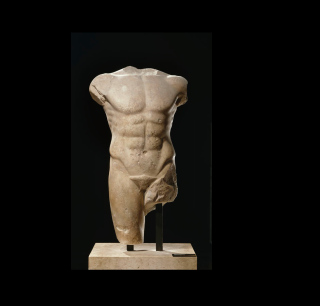

Medusa, handmade copper chain mail

Susie MacMurray is back with another solo show, Hinterland, at Danese Corey. I plan to be there for the opening reception next week and hope to talk with her in person about the new work, which arrives less than three years after her last solo show in Chelsea. From this distance, it looks like another knockout. I’m eager to see it up close.

April 3rd, 2016 by dave dorsey

Symmetrical book stacking. If you feel the need to call Ghostbusters, call Bill himself and leave a message, not the new crew. His 800 number is out there somewhere. but Peter Venkman’s irony in the New York Public Library–“No human being would stack books like this”–wouldn’t apply here. It’s a stack of books that works like a blog post–except I can’t imagine it will stick around for long. I wonder how long blog posts will last?

Symmetrical book stacking. If you feel the need to call Ghostbusters, call Bill himself and leave a message, not the new crew. His 800 number is out there somewhere. but Peter Venkman’s irony in the New York Public Library–“No human being would stack books like this”–wouldn’t apply here. It’s a stack of books that works like a blog post–except I can’t imagine it will stick around for long. I wonder how long blog posts will last?

March 28th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Carpe Diem, Autumn’s Last Flowers, oil on linen, 30″ x 52″

To the same collector in Connecticut. For sales, it’s been the best consecutive 18 months I’ve ever had thanks to Jim and Jinny Hall at Oxford Gallery.

March 26th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Breaking Free, Cutting Loose, oil on linen, 49″ x 49″

To a collector in Connecticut.

March 22nd, 2016 by dave dorsey

Yellow Hat, 1936, Norman Lewis

The reappraisal of Norman Lewis, decades after his death, nice story from CBS.

March 19th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Young Possum

Henry James’s critical genius comes out most tellingly in his mastery over, his baffling escape from, Ideas; a mastery and an escape which are perhaps the last test of a superior intelligence. He had a mind so fine that no idea could violate it…. In England, ideas run wild and pasture on the emotions; instead of thinking with our feelings (a very different thing) we corrupt our feelings with ideas; we produce the public, the political, the emotional idea, evading sensation and thought…. Mr. Chesterton’s brain swarms with ideas; I see no evidence that it thinks. James in his novels is like the best French critics in maintaining a point of view, a view-point untouched by the parasite idea. He is the most intelligent man of his generation.

–T.S. Eliot

I reread “The Beast in the Jungle” today, after being reminded of it by reading John McGahern’s “The Wine Breath,” which was first published in The New Yorker in 1977. So I was led back to this quote from Eliot, which I’ve always loved. We need more and more painters who have that same kind of intelligence.

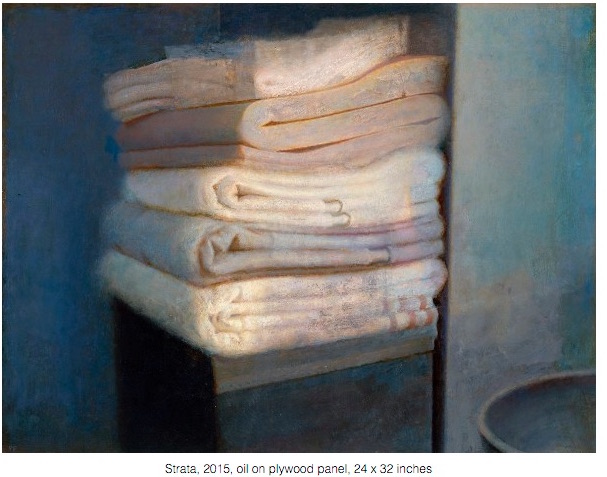

March 14th, 2016 by dave dorsey

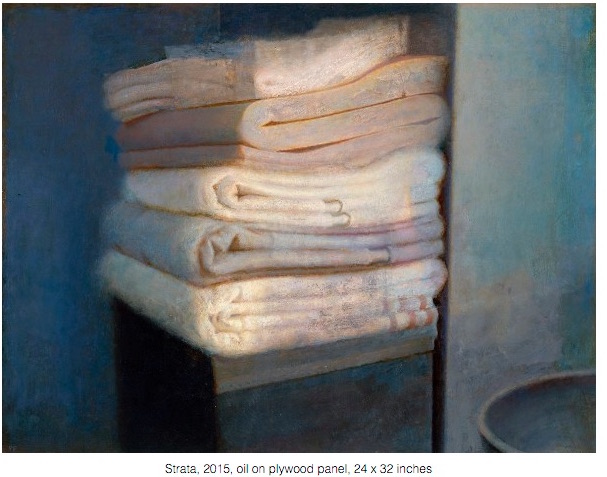

This is an uncharacteristic still life at Paul Fenniak’s show comprised mostly of dream-like narrative scenes of people who seem adrift or maybe sleepwalking and not at all sure what to think about it, now at Forum Gallery. The texture of the paint itself evokes the texture of the folded cloth and what appears to be a strip of foam rubber carpet pad he’s slipped in near the top. Likewise, the lyrical column of blues and purples on the right, representing the nearest wall, relies on scumbled layers of paint to give you the feel of plaster. So many blues flickering in that chiaroscuro.

March 11th, 2016 by dave dorsey

At my old haunt, Viridian. Deadline, April 9.

At my old haunt, Viridian. Deadline, April 9.

March 9th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Harvard Murals, Mark Rothko

There’s no substitute for the actual painting. The physicality of paint matters. This was nicely put earlier this month in a letter to the editor from The New Yorker, Feb. 1, 2016,

THE RESTORER’S ROLE

In discussing the digital component of the artist Josh Kline’s work, which relies on technology that doesn’t yet exist, Ben Lerner makes a comparison to the computer-generated restoration of the “Harvard Murals,” a suite of paintings by Mark Rothko. In the early nineteen-sixties, as an apprentice in the conservation department of Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum, I was among the crew that worked with Rothko on the installation. Lerner describes the murals’ recent exhibition at the Harvard Art Museum, in which color that was fading was made more vivid by the projection of computer-generated hues. Lerner suggests that the original art may not be necessary if projectors could produce the same effects. As the former head of conservation at the Harvard University Art Museums, I disagree. I maintain that the experiment with projected color brought us closer to that of the originals. Lerner did not see the exhibition, but, had he been there, he would have been able to experience the haptic effect of Rothko’s brushwork, seen on a huge scale. The colored light did not obscure the painter’s application of layers of various media—egg white, glue-size, oil—that suffuse the clouded, glowing expanse of canvas. Hue and substance were reintegrated. Though Lerner questions whether “the present’s notion of its past and future are changeable fictions,” he gives short shrift to the aim of conservationists, which is to find ever more accurate and responsible methods of preserving and restoring original works of art.

Marjorie B. Cohn Arlington, Mass.

March 6th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Bill Santelli and Bill Stephens, at Tom Insalaco’s home

The three of us visited Tom Insalaco in Canandaigua and had lunch. What I took away was Tom’s comment during lunch: “An artist has to be myopic.” Yes. It’s the hardest thing: to eliminate the distractions, focus on painting as the dominant activity in life, and narrow the creative range to exactly what you most want to do–but I think he really meant to say, don’t venture off track, in the work itself, often or for long. They were looking through the deep stack of marvelous portrait drawings Tom does every morning, working on them before breakfast. It’s his way of waking up.

March 3rd, 2016 by dave dorsey

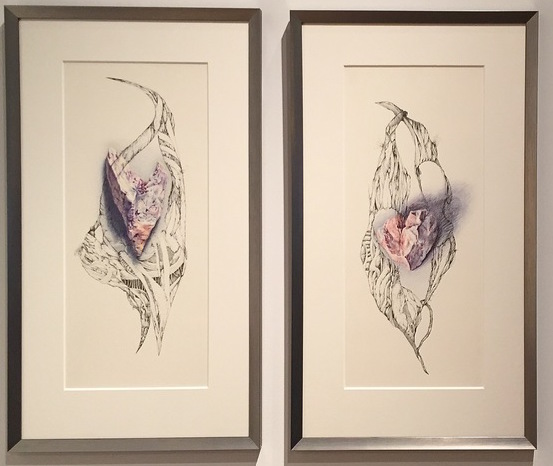

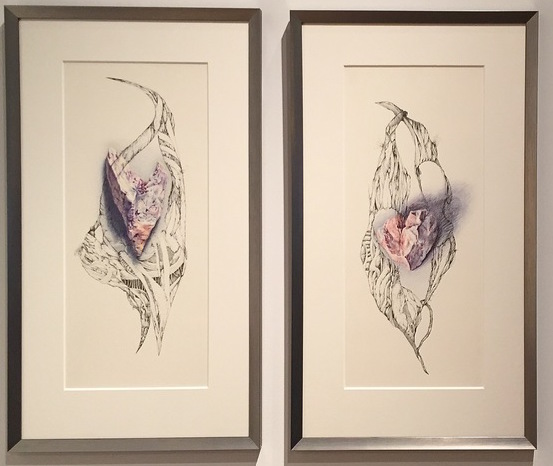

Bill Santelli and I paid our first visit to Maker’s Gallery and Studio this week to get a look at a diptych by Bill and Jean Stephens, part of a “Diptych: A Valentine’s Day Group Show” curated by Alex and Anni Gruttadaro, the gallery’s owners. They’ve created a hospitable and friendly place to see work and hang out, part living room, part studio, part coffee bistro. Alex literally did plumbing, woodwork and helped pour the concrete countertops for his space, and it has the raw-finished feel of a contemporary urban loft, with painted brick walls and exposed rafters. (Alex drives a Ford F150 and works as a contractor to support his painting and the gallery.) Alex and Anni, who opened the gallery last summer and use it as their studio, contributed a diptych of their own, a pair of half-nudes, showing Alex side-by-side with Anni, their faces and most of their anatomy cropped out of the image, beautifully done, with subtle modeling of the figures and a faint wallpaper pattern for a background, hinting at Kehinde Wylie, but pleasantly lacking his postmodern irony. All of the work in the show is fascinating, but I came specifically to see the contribution from Bill and Jean.

Their collaboration was a surprising increase in scale–Bill has been experimenting with improvisational line drawings over the past year, mostly in small sketchbooks, often accompanied by text. This time the work is larger, leaving more space at the center for Jean to elaborate on the rocks she places inside these husks that remind me of dried milkweed pods. I’ve admired what Bill has been doing with the smaller drawings, the intricate, imaginary organic spaces he creates using fine-point pens: my sense is that they evolve as he puts down marks, with a general shape in mind, like a jazz riff meandering around a melody. With the concentrated muted colors of Jean’s rock at the center, the images serve as a perfect fulfillment of the idea for the show: how a man and woman can work together, in life and art, creating something that adds up to more than the sum of its parts.

Jean has been doing a series of bird’s nests for quite a while, and the polarity of egg/nest in those images becomes even stronger in this diptych, so that these two drawings become almost a deconstruction of her usual work. The egg in her earlier nests here becomes a heart-shaped rock, colorful as a hatched bird with folded wings, but permanently earthbound. The protecting swaddle of the swirling twigs becomes Bill’s intricate and less confining fretwork. This shape, and many of his other drawings, remind me of a milkweed pod after it launches seeds into the wind–the botanical equivalent of a nest. The image is warm, inviting, and complete, but without an easy stability. It plays with the idea of a nest the way Picasso played with a face, creating uncertainties and multiple points of view. If you look the drawings long enough, you realize Jean’s rocks cast shadows over Bill’s line drawings, in a trompe l’oeil effect, flattening his lines back into the surface of the paper as her rocks seem to rise up and out into all three dimensions, even as they stay in place. (A nice metaphor for most negotiations with my wife.) It may have been created to celebrate Valentine’s Day, but this work suggests the happy teamwork and truces of marriage far more than romance, and it resonates less with Cupid’s heat than the isometric warmth of enduring love.

“Diptych: A Valentine’s Day Group Show,” featuring the work of artist couples Bill + Jean Stephens, Alex + Ani Gruttadaro, Cordell + Rachel Cordaro, Clay Patrick McBride + Sarah Keane, Rob + MandiAntonucci, and Duncan + Alisia Chase. “Diptych” opens on Valentine’s Day, which is Sunday, February 14, 3 p.m. to 8 p.m., and continues through March 14.

March 1st, 2016 by dave dorsey

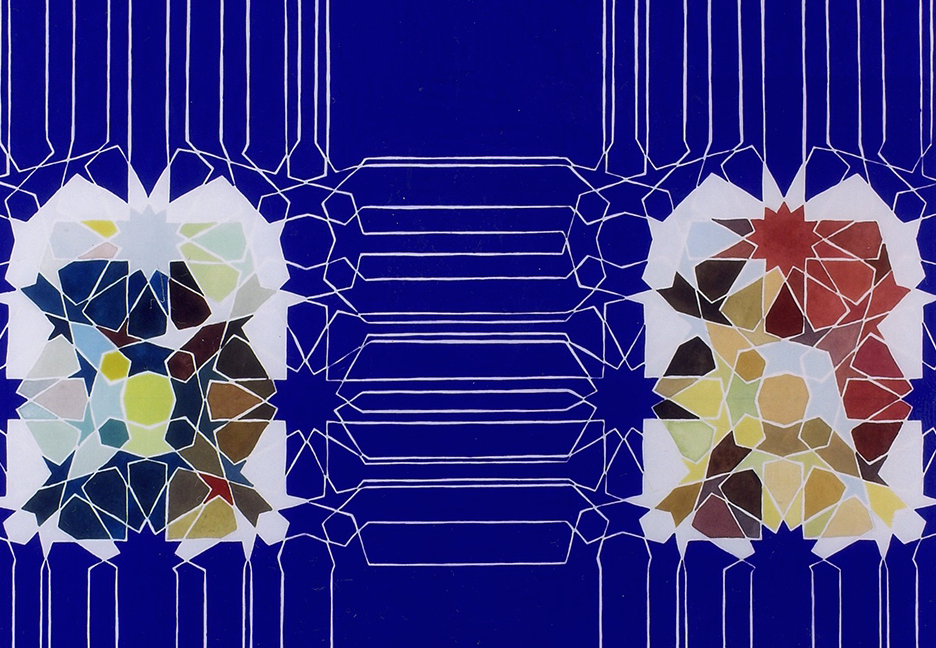

Je Est Un Autre

I is an other. — Rimbaud

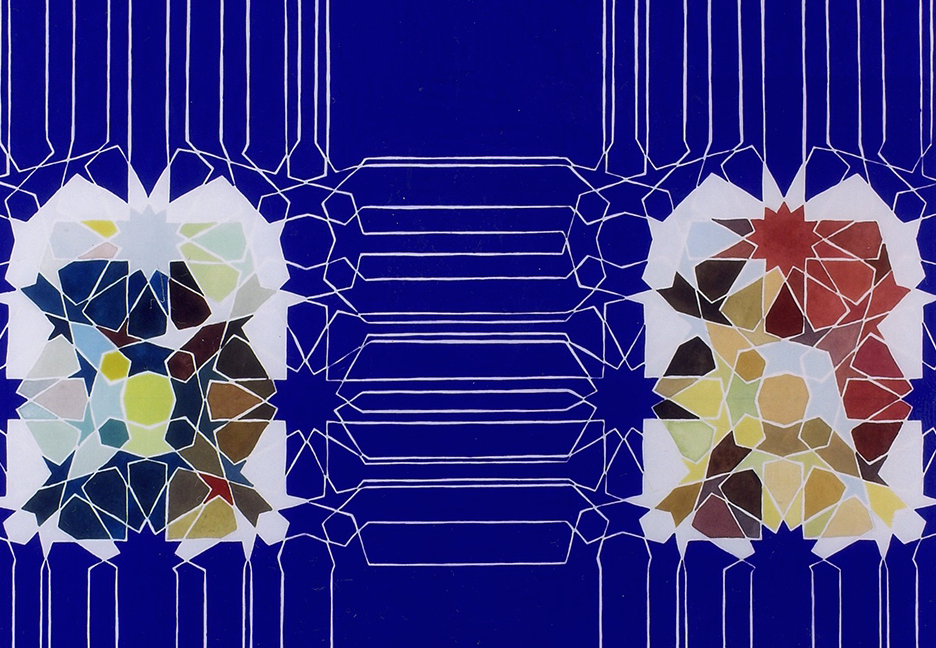

In my current re-immersion in Matisse, I’ve been reminded of how deeply he was influenced by the East, both in his Tangier sojourn, and in a journey he made to an historic exhibit of Islamic art in Munich, in 1910. He embraced the hedonism of sunny Tangier, but he was also moved by the peace and order of its religious imagery. He discovered the power of pattern–as a way to free himself from post-Impressionism, reaching for abstraction without completely surrendering to it, and he recognized how what may seem purely decorative can become laden with subtle meaning unavailable to the Western tradition, at least until the 20th century. The mathematics embodied in Islamic designs are assumed to be serendipitous anticipation of geometric insights developed in the 20th century, or were a visualization of math within Islamic intellectual culture (Persian society once considered science and mathematical exploration to be an integral, central part of human life). I’ve always been drawn the fractal patterns of Persian carpets my larger still lifes because of the suggestion that math and science are consistent with a vision of life as sacred. Braque and Burchfield rooted their work, as well, in decorative elements that bore far more meaning than mere ornament: Braque’s father had been a house painter, and he apprenticed early on with a master decorator–his ability to mimic various surfaces of marble, stucco, and wallpaper became crucial in his mature work where it gave the flat surface of a painting a timeless resonance, like a fossil record of daily life, far beyond its representational signifiers. Burchfield, as well, worked as a wallpaper designer, as a source of income, and his emphasis on patterns becomes one of the crucial ways he conveys forces of nature in his most original watercolors–summer insect sounds look like arabesques of rising smoke. In my Googling, I happened across this site of a contemporary artist also deeply influenced by Islamic art: Navine G. Khan Dossos, aka, Vanessa Hodgkinson. As it did for Matisse, Islamic art frees her to find color harmonies that would probably be unavailable in a more representational image, and the effect is musical. She relies on qualities of Islamic “decorative” design, but in a conceptual and more political way. I love the color and the self-effacing way it’s presented in regular grids–how individual expression surrenders the stage to the discipline of repetition and regularity. Echoes of Stella, and many others, as well as Mecca. And like Blake, she forsakes oil in favor of water-based paint, with an affection, similar to his, for the early and mid-Renaissance. For me, the effect seems closer to Byzantine mosaics.

February 29th, 2016 by dave dorsey

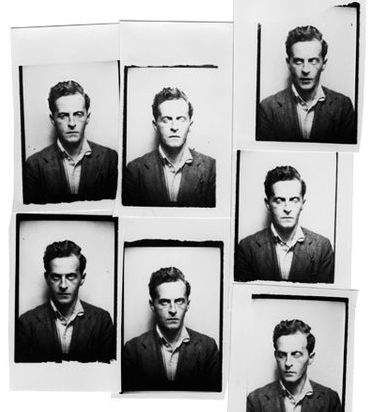

Wittgenstein’s self-portraits in a photo booth.

” . . . certain propositions seem to underlie all questions and all thinking (On Certainty, 415).” — Wittgenstein, on “hinge propositions”

That’s a quote from Wittgenstein, in his last book of notes, published after his death. It intrigues me because of the notion that something pivotal and impossible to prove underlies thinking itself–yet isn’t knowledge. He’s talking about his notion of “hinge propositions.” For him, they are simply a given, an unquestionable element of the world. It makes no sense to doubt them unless you doubt everything else in the world. I believe this would qualify as a hinge proposition from Little Orphan Annie: “The sun will come up tomorrow.” This example makes it sound as if a hinge proposition is just something so obvious no one would think to question it. Or notice it, for that matter. I think he was exploring the idea in order to circle around something harder to say: such as, what’s ever-present is sometimes impossible to single out and scrutinize. (But that isn’t it either.)

Since I went back to reread On Certainty last year, this idea of hinge propositions has been on my mind relating to the role painting can play in human awareness. I have been thinking of this term as a distant metaphor of how art works–as well as the mind itself.

I think all forms of art can have a particular kind MORE

February 27th, 2016 by dave dorsey

We interrupt our scheduled postings for this bulletin from Louis C.K., one of the few people in this world who has the power to make me happy. And he deigns to do so repeatedly. From my inbox today:

We interrupt our scheduled postings for this bulletin from Louis C.K., one of the few people in this world who has the power to make me happy. And he deigns to do so repeatedly. From my inbox today:

Good morning. Indeed this is my weekly email, notifying you that the new episode of Horace and Pete (5) is ready for download ($3). Go here to watch it! Enjoy.

I know that some of you on this list don’t want to get this email every week. And I know that some of you really like getting this email every week. I know this because I get emails from both of you. Some people write me and they say “Hey, you promised not to write me all the time. This is REALLY unfair! This is SPAM!” and some of you write me to say “Hey man. I love getting these emails. And thanks for reminding me about the show this week.” Also, whenever we delay the email for a while, to see if maybe people will come out of habit to watch the show, some do. But not many. And then I send out the email and boom. There’s an explosion of sales on the new episode and even the old ones. And the explosion reverberates though the week. So. I’m gonna keep sending the emails.

You may be asking yourselves, or asking me, though within yourselves, “Why don’t you just let some people opt out of the Horace and Pete email list?” Well, the fact is that I did tell my web guys to create some category options for the email list. And to be fair for them, they did that very thing. And they emailed me a few days ago, showing me those options and asking me to review and approve them. And I haven’t looked at it. Because I’m very busy right now doing lots of things like, for instance, taking my kids to school in the mornings, picking them up later, politely asking the dog not to chew things, building a Trump shelter like everyone else, creating and paying for a whole television series and distributing it to you directly. So yeah, I’m fucking busy. Sorry for cursing.

So for the time being, you’re going to get one of these MORE

February 25th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Agnes Martin

“I don’t have any ideas myself. I have a vacant mind. In order to do exactly what the inspiration calls for. That’s really the trouble with art today. They have inspiration but before they get onto the canvas they have about fifty ideas and the inspiration disappears. The best art is music. The highest form of art. Completely abstract. I don’t believe what the intellectuals put out. They discover one fact and another fact and they say that from all these facts we can deduce so and so. That’s just a bad guess. I gave up all the theories. That leaves me a clear mind. So when something comes into it, you can see it.” –Agnes Martin

Bill Santelli sent me a link to this great, short video about Agnes Martin. Her comments say it all.

February 20th, 2016 by dave dorsey

There is no place that does not see you. You must change your life. –Rilke

“After he left the Louvre, (Rilke) continued to eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The challenge that he issued in his poem was, rather, an inward challenge—whether the refreshment of the senses and the refinement of the mind that attends an experience of art can be made somehow to last, so that one comes to live more significantly in the commonplace, at a higher plane of consciousness.”

Leon Wieseltier, The Atlantic, “Critic Without a Cause”

February 19th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Jim Mott sent these further thoughts, after our conversation about his last itinerant art project:

Jim Mott sent these further thoughts, after our conversation about his last itinerant art project:

The 2015 tour was my longest IAP road trip since 2000, when I launched the project with a 2 1/2 month coast to coast journey. Shorter regional and local tours have proven more sustainable, and I figured 2015 would probably be my last cross-country tour. This inspired considerable reflection and prompted me to revisit some of the key hosts from the first tour. Dave Chappell, the Civil Rights historian, was one.

I’d met Dave back in the 1980s, when he was a grad student at the University of Rochester under Christopher Lasch.

I should mention that my exposure to Lasch’s thought and personal example (I knew him as a family friend and worked for him as a research assistant for a semester) had a strong influence on my thinking and, ultimately, on my formulation of the Itinerant Artist Project – providing some of the intellectual underpinnings as well as the desire to become more than a Minimal Self (the title of one of his follow-ups to The Culture of Narcissism).

Dave influenced my project in more specific ways: he got me to read “Blue Highways,” which must have helped me to imagine, 15 years later, using a road trip as a vehicle for creative engagement. And, when I needed a nudge to get on the road for my 1st cross-country tour, I decided to think of it as a good pretext for visiting Dave in Arkansas, where he’d ended up.

This time, in October 2015, the visit was short and sweet, and when dusk fell the first evening there was about half an hour when a seemingly very ordinary neighborhood in Norman OK became so wonderful to look at that I almost couldn’t bear it. I’m afraid this painting of my car in Dave’s driveway serves more as a shorthand reminder for me than as an evocative transcription of the enchantment that twilight delivered.

I suspect that, along with the enchantment of twilight, something else was at work. I call it the Oklahoma Effect, and it has happened to me whenever I’ve driven across the state. A few hours on the Oklahoma highway induces such a sense of endless, rootless desolation that whatever particular things I see when I stop – weeds, fence posts, someone pumping gas at a service station, birds on a wire, chunks of gravel on the side of the road – feel wonderfully and miraculously actual and present. Dusk maybe just reactivated the effect.

The phenomenon of seeing unexpected depth of beauty in everyday things reminds me of something Joan Acocella recently wrote in the New York Review of Books:

“When critics speak of a writer’s ear, this often carries a political implication, of the democratic sort. They are talking about writers (Mark Twain, Willa Cather) whose world, by virtue of being humble, would seem to exclude beauty and music, so that when the writer manages to find in it those riches, the world in question – and, by extension, the whole world – comes to seem blessed.”

When that thought is enlarged to include the visual arts – landscape painting, for example – it articulates as well as anything my primary motivation for pursuing art: to attempt to cultivate and to share that kind of insight, that kind of discovery.

The underlying principle expressed by Acocella might be called “the gospel of beauty” – a term coined by the early 20th century poet Vachel Lindsay, who didn’t mean quite what I mean by the term. Lindsay did, however, wander the United States for a few years trading poems for food and lodging. I learned of him after I started my own project of aesthetic itinerancy.

Once upon a time there was an American type called “the gentleman vagabond” – presumably a person who was not forced by circumstances to be a tramp but who wanted to see the world in an unencumbered way. Some individuals of this type were motivated by ideals that conventional life didn’t leave enough room for. Or they were intent on sharing life with other people in ways that maybe required the context of the road, or of the journey, to make sense.

Lindsay wrote a book about his vagabonding called “Adventures While Preaching the Gospel of Beauty.” For years I took encouragement from the very fact of the book’s existence, its great title. I expected to like the story as well, when I finally tracked it down, but the personality that comes through is insufferable. I’ll just say that Lindsay’s ideals were linked to a level of self-righteousness and delusion I hope I’m able to avoid in the pursuit of my ideals.

Maybe we can all be forgiven for preaching now and then, but not to the point of eclipsing dialogue, which is the essential thing. Especially if one is on a journey.