Archive Page 35

February 5th, 2014 by dave dorsey

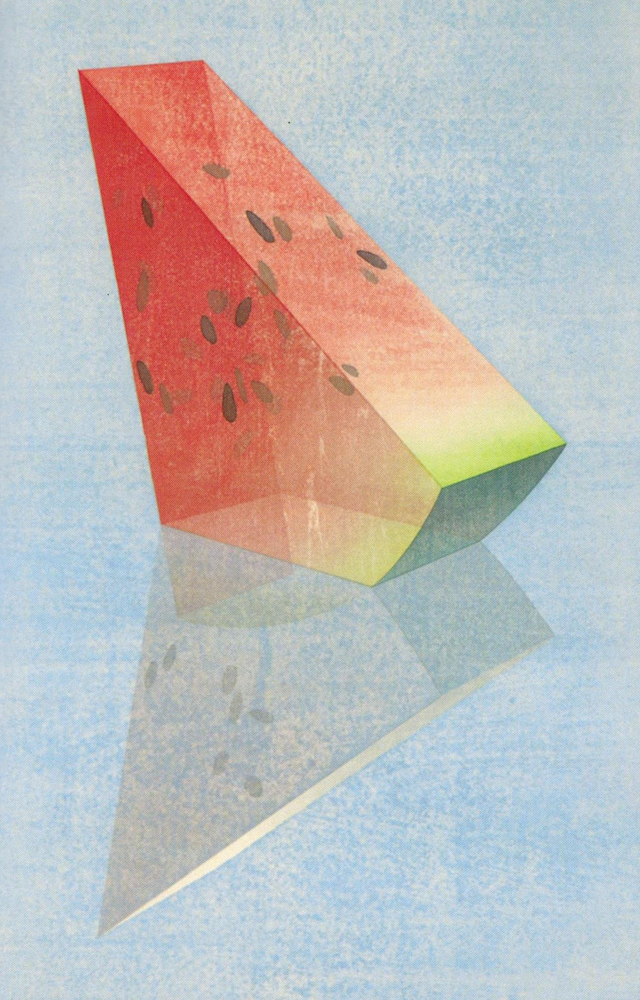

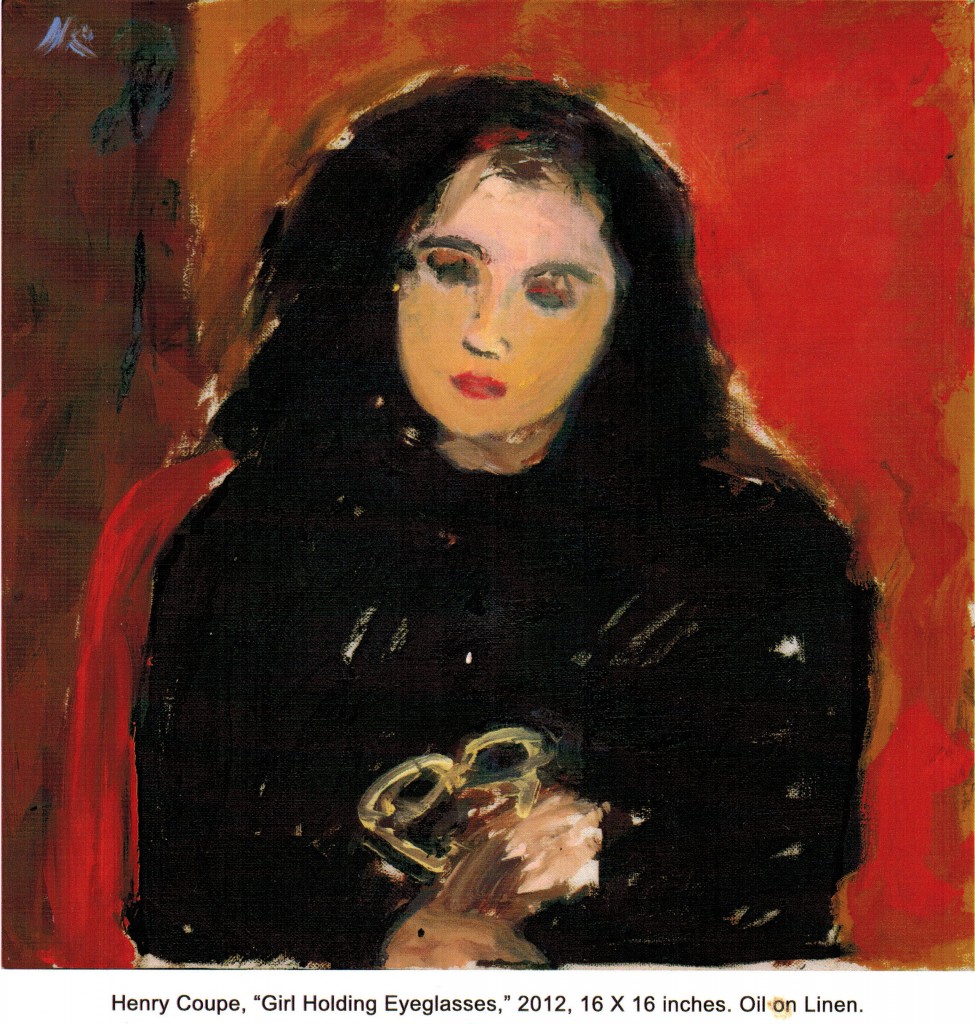

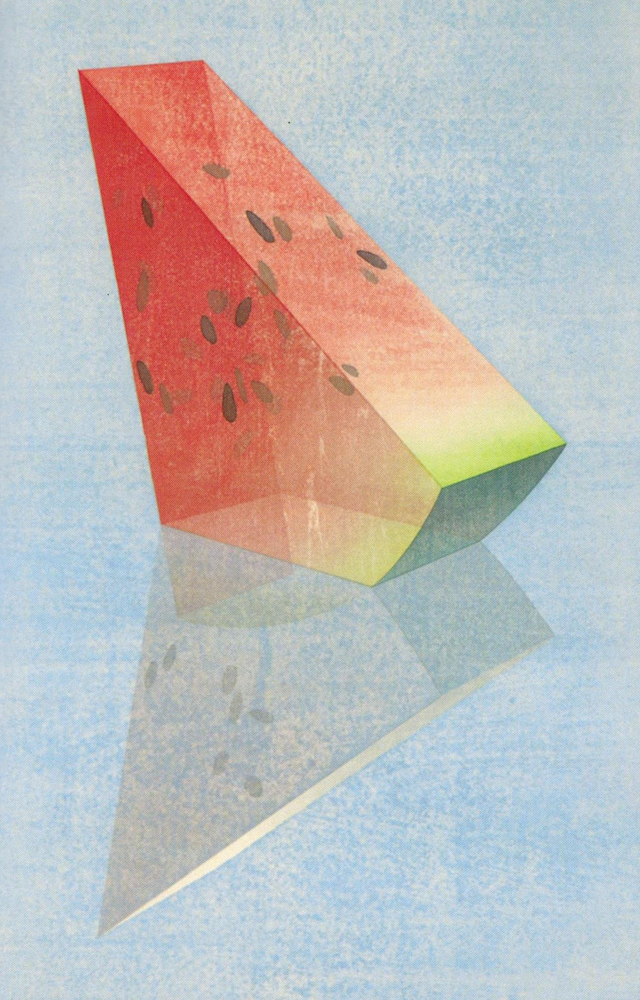

Surfacing Watermelon, Shoji Miyamoto, Japanese woodblock

A fantastic show of work from 13 contemporary Japanese artists, at the Memorial Art Gallery, stuck me as a thrilling demonstration of how an obsessive focus on something as impersonal as method can generate original, idiosyncratic work that’s emotionally powerful and wonderfully expressive. I’ve been working on work for a small solo show in June at Viridian Artists, built loosely and maybe a bit whimsically around the idea of polarity, so I was primed to be dazzled by what I saw here. All the work here levitates in the mind, lofted by the magnetic poles of opposing forces: the abstract work hints beautifully at representation and the most representational work hews faithfully to narrow formal constraints. The rigor of technique disciplines, unobstreperously and almost politely, intense personal passions: you can feel the Japanese adherence to self-effacement in the strictures these artists have applied to what they do, and yet, at the same time, these self-imposed boundaries seem to heighten the passion. It’s like watching The Age of Innocence, start to finish, in a single glance. What you end up with is highly refined mastery, and remarkably some of these artists appear to be only a few years into their careers.

Curated by Sam Yates, of the Ewing Gallery of Art and Architecture, with a MORE

February 3rd, 2014 by dave dorsey

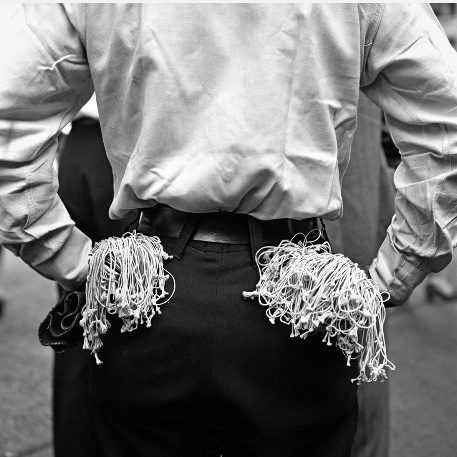

The third floor of Rod Stewart’s Los Angeles home contains a model railroad layout that measures 23 X 124 feet, and he estimates that he has at least another three years before it’s complete. Is it a work of art? In the Daily Beast, Malcolm Jones thoughtfully suggests that maybe it is. In a world where a diorama counts as art, why not? It’s a miniature representation of some part of the world, in three dimensions, after all. There’s a passage in the piece that makes me want to agree:

I laughed when saw the story. And then I began reading about the depth and breadth of his zeal (he has two assistants, he rents an extra hotel room on the road when he’s performing for designing, building, and painting the structures that populate his layout). Then I studied the photographs in the magazine closer—and the more I looked, the more impressed I became. The attention to detail, coupled with carpentry skills and a painter’s eye (he’s colorblind and someone has to check his reds and greens, but still), strongly suggest that here is an artist—a nutty artist, maybe, but an artist.

February 1st, 2014 by dave dorsey

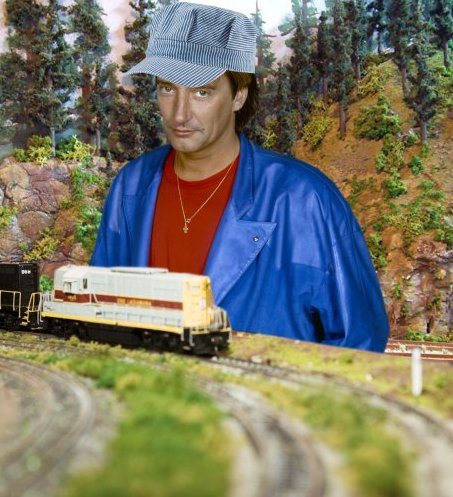

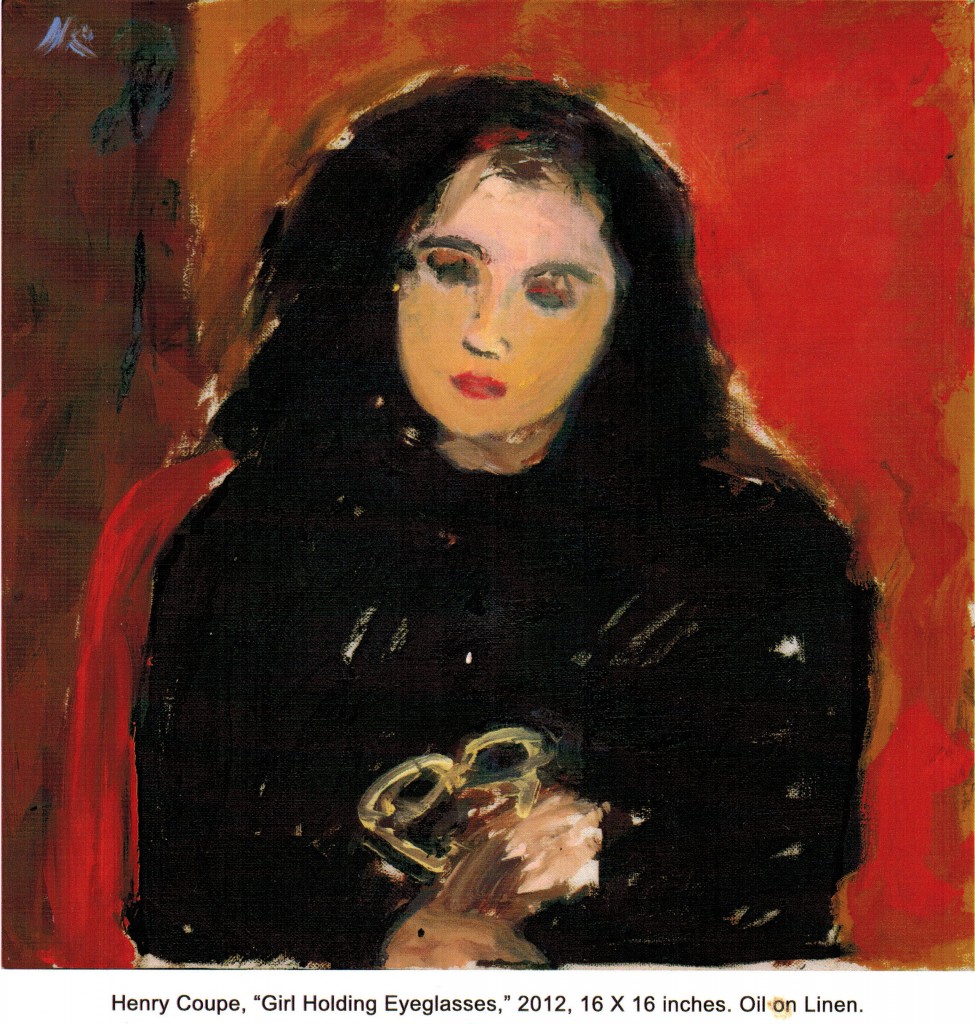

The Letter, Henry Coupe, oil on linen, 10×16

Henry Coupe, one of the most recent new members at Viridian Artists, has finished his career as an artist, but I hope his reputation has only begun to gain momentum. All his life, he struggled with various degrees of vision impairment, and yet he lived for painting. He deserves a lot more attention than he got while he was actually creating art, and if I had the money to be a collector I’d be grabbing a room full of his canvases right now. His work, mostly very small, does exactly what much of my favorite painting invariably does: it calls my attention to the quality of the paint itself, purely as paint, while it evokes something that takes me away from the medium and into a dream. That polar struggle between the physical reality of a canvas and what it fools you into seeing is at the heart of why painting matters, for me–and Coupe also has a sense of color that’s both somberly beautiful, but somehow also conveys solitude, isolation and yearning. He studied in Utica with a student of Hans Hofmann, where he grew up and lived all his life, and his work shows not just his love of expressionists like Kirchner, but, like Hofmann, a strong sense for simplifying areas of pure color, composed with an eye to the abstract pattern he assembles on the surface. His sense for color is akin to what Louisa Matthiasdottir–who studied directly with Hofmann–achieved in her brilliantly simplified scenes of Iceland, which are as colorfully intense as a Hodgkins canvas. Coupe’s color can be just as evocative as hers, but in ways it’s more elusive and mournful, submerged in an aura of darkness from which his figures always struggle to emerge.

I stopped in Utica to meet his wife, Ann, a while ago and spent the MORE

January 30th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Breezeway, Ray Hassard

My favorite painting in the current two-person show at Oxford Gallery, looks both effortless and masterful. I love the way the pickup’s two tail lights vary in terms of the color’s saturation, which somehow looks entirely realistic and yet may just be an artifact of Hassard’s confident brushwork. Or the sun is hitting one directly and not the other. I’m guessing that’s a riding lawnmower in the foreground, shaded, under the arch, but it doesn’t matter what it is. Identifiable or not, it’s perfect. He’s one of the best pastel artists in the country, and most of the work on exhibit here is pastel, but he’s just as good with oil. Also in the show are Patricia Tribestone’s intensely colorful still lifes. Coming next month to Oxford: two artists I love in a three-man show: Rick Harrington and Matt Klos.

January 28th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Billy, the Magical Dog, in Los Angeles

This is an interesting Boston Review article that not only buries the lede, but obscures its thesis a bit by talking in circles around it. The core of it is the notion that dogs can teach us to eliminate the boundary between physical and mental through a different order of attentiveness and “obedience” to what’s actually happening around them. In other words, dogs are models of mindfulness–which never gets said in quite that way. The easier and more attention-getting point it keeps making is that dogs aren’t people–since most of us mistakenly treat them as if they were. By anthropomorphizing them, we diminish their greatest virtues and so on. The real point of the article is that people aren’t canine enough. People should strive to be more like dogs:

Dogs live on the track between the mental and the physical and seem to tease out a near-mystical disintegration of the bounds between them. Their knowing has everything to do with perception, an unprecedented attentiveness that unleashes another kind of intelligibility beyond the world of the human.

Unleashes. (That must have been too tough to resist.) “Another kind of intelligibility” comes and goes here, but that phrase made me stop and smile. “A knowing that has everything to do with perception,” not reasoning or conceptual thought, is what, for me, painting is all about. The ideas, the concepts, the implications of a painting beyond what perception alone conveys (and the point in this article is that perception alone can convey a world of immediate understanding and reaction that doesn’t require thought) these chimera can attach themselves after the fact, even with a purely perceptual painting, yet for me that’s the proper order. First the painting; then the idea. I’d like to think that Duchamp’s Fountain happened at the moment when he found himself involuntarily admiring the curving forms of a urinal, despite himself, and then probably realizing that a sculptor could have made it, and exhibited it, and then . . . well, Pop art followed with all of its preconceived ironies and poses, generating the flood of work it has produced. Yet it began with a simple perception, an awareness of how difficult it can be to differentiate between life and art. And even that thought was after the fact of the simple perception of beauty in the forms of something Duchamp was conditioned (by thought) to see as nearly the exact opposite of art, the lowest object imaginable, because he knew its purpose. So he turned his perception into a highbrow joke. It really is a fountain, and the more you think of it as a fountain, the more laughs you’ll get out of Duchamp’s humor, yet the more you think, the further you get from the original, unsullied perception of the formal qualities in that porcelain object that set in motion the whole notion of exhibiting a urinal. What has bothered me about art, at least since Duchamp, is how perception, which is the heart of visual art, has so often been subordinated to the ideas that arise around it, or that, at its worst, art becomes merely an illustration for an idea, a visualization of a thought. The ideas should be at the end of the process of struggling with the formal challenges of a medium, not at the start, in my humble opinion. It’s the pursuit of “another kind of intelligibility” unavailable to the calculating, reasoning mind: Duchamp had that at the moment he paused to keep looking at the urinal . . . and then his calculating mind took over and we’re back in the world of commonplace intelligibility, and a “stance” about art and the art world in general, implied in the humor and scandal of exhibiting a urinal as a work of art.

Painting can dissolve the boundary between mental and physical and produce, as it happens, a different kind of exuberance about life that has everything to do with having more awareness than opinions about it. So, all of this only confirms what my wife has often thought: yes, I’m a dog.

January 26th, 2014 by dave dorsey

My cow skull

A little Zen pun up above to brighten your day. Every morning in my studio, this cow skull that Susan Sills kindly gave me, sits on that stool and doesn’t actually say Mu, like Joshu, but it does whisper tempis fugit. Always showing off its Latin. I just say, thanks Boss. (Which is close enough to the Latin for “cow.” Bos.) I know all about it at my age. Time flies. But I get more painting done when I’m reminded.

January 24th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Edwin Dickinson, Snow on Quai, Memorial Art Gallery

One of Dickinson’s premier coup paintings, an exhilarating find for me, at the Memorial Art Gallery, where I took this shot yesterday.

January 19th, 2014 by dave dorsey

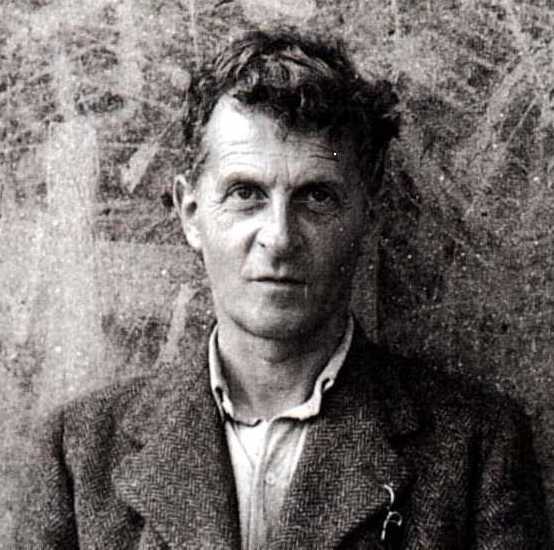

Art can show you what’s right there in front of you, but you don’t really see it, you aren’t fully aware of it, until art represents it. This passage from Wittgenstein is confusingly worded, but I’m sure he meant “imagine a curtain goes up and you see yourself, walking up and down, lighting a cigarette, sitting down. . . ”

Let us imagine a theatre; the curtain goes up and we see a man alone in a room, walking up and down, lighting a cigarette, sitting down, etc. so that suddenly we are observing a human being from outside in a way that ordinarily we can never observe ourselves; it would be like watching a chapter of a biography with our own eyes — surely this would be uncanny and wonderful at the same time. We should be observing something more wonderful than anything a playwright could arrange to be acted or spoken on the stage: life itself.

But then we do see this every day without its making the slightest impression on us!

–Wittgenstein

January 15th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Self, Valerii Klymchuk

In the current solo show at Viridian Artists, you can get a sample of work from one of our youngest members, who immigrated from Russia only a few years ago: Valerii Klymchuk. Many of his images make me wonder if he believes, as Heraclitus did, that the world is made of fire, and his sense of color is intense, personal and lyrical. He’s a brilliant young man, who got into a program at Columbia University to study big data, but couldn’t afford the tuition. He has the look of a young man out of a Dostoevsky novel, or one of those contemporary Russian Orthodox monks in the book Everyday Saints. Maybe if he sells one or two paintings, at the prices he’s asking, which have always made me smile, he can get his coursework done at Columbia. He has a bit of that Warhol impishness about him: half the time, I can’t tell if he’s putting us on or if he’s dead serious, but in these answers there’s very little irony. He hasn’t been painting long, but he has a kind of courage to do anything that occurs to him, in his work, that would rarely occur to a career-minded painter as an option these days. I sent him a few questions, and rather than try to filter his thinking, I’m passing most of it along as he sent it to me. He sounds Russian, even in his writing:

You took up painting without studying it in school right?

I just started doing art without any previous studying. It happened spontaneously, during one of the hardest periods of my life when I was desperate to find meaning in my life, struggling to find my own place in this world. I was introduced to painting by a friend in New Jersey. He hosts painting sessions at his house, where he and his friends sit down on the floor painting.

Before that day, I never considered myself an artist, and I never thought I had artistic talent. Just the opposite—I thought that I had no talent in painting whatsoever. My sister could paint, and I knew that I was good in mathematics and sciences, but I thought that painting was something absolutely foreign to me. I never had any tendencies to express myself in painting before.

Only when I painted for the first time at my friend’s house . . . was I surprised to MORE

January 14th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Betty Woodman, June in Italy, detail, 2001

glazed earthenware, epoxy resin, lacquer and paint

Apropos of nothing, a small sample of work from our greatest living colorist, Betty Woodman, who does ceramics which, for me, are really three-dimensional paintings that put Stella’s constructions to shame. The tragic brilliance of her daughter’s photography may have eclipsed Woodman’s Matisse-class talent with color, but her work is a humbling joy, every time I return to it.

January 12th, 2014 by dave dorsey

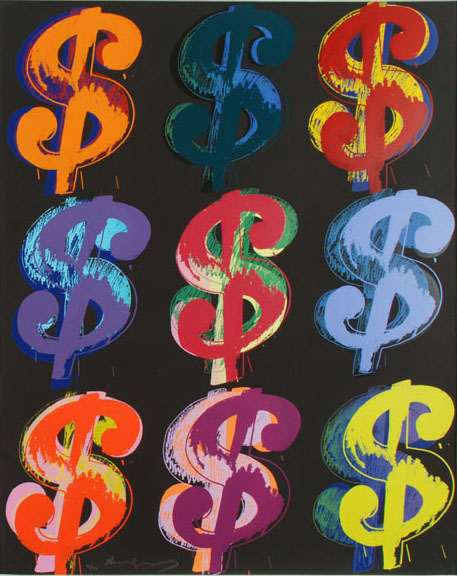

Why it becomes harder and harder to make an ordinary living from painting. (As if it was ever a sensible career path for the merely talented.) Robert Frank in today’s NYTimes: “(Income) inequality in the United States has been increasing sharply for more than four decades and shows no signs of retreat. In varying degrees, it’s been the same pattern in other countries. The economy has been changing, and new forces are causing inequality to feed on itself.

One is that the higher incomes of top earners have been shifting consumer demand in favor of goods whose value stems from the talents of other top earners. Because the wealthy have just about every possession anyone might need, they tend to spend their extra income in pursuit of something special. And, often, what makes goods special today is that they’re produced by people or organizations whose talents can’t be duplicated easily. Wealthy people don’t choose just any architects, artists, lawyers, plastic surgeons, heart specialists or cosmetic dentists. They seek out the best, and the most expensive, practitioners in each category. The information revolution has greatly increased their ability to find those practitioners and transact with them. So as the rich get richer, the talented people they patronize get richer, too. Their spending, in turn, increases the incomes of other elite practitioners, and so on.”

January 10th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Eric Hollenbeck, craftsman

This short video about a woodworker captures one of the most central reasons I paint: to make something carefully and skillfully by hand.

January 8th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Close at work

“Persistence: we call it getting to know the Muse.”

- Writer E. B. White: “A writer who waits for ideal conditions under which to work will die without putting a word on paper.”

- Painter Chuck Close: “Inspiration is for amateurs–the rest of us just show up and get to work.”

- Composer Peter Tchaikovsky: “A self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood.”

—Fast Company

January 6th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Dragon, by J.R.R. Tolkien

What amazes me is that Tolkien actually had time to produce the quantity of art he did, with such assiduous attention to detail. Love this dragon, a sort of Celtic ornamental design. It’s about as far as a dragon can be from the one in the theaters at the moment, which reminded me of the badass winged lizard in Reign of Fire. Which is a beast the evil corporation in Alien would want to weaponize. Am I watching too many movies? No. Yes.

Most of the Tolkien art at Brain Pickings remind me of Jung’s artwork. The illustration, below, of “Undertenishness”–the spiritual state of being younger than ten years old (sounds like a German word–is like a poem. A path toward the horizon that’s actually moth-ride to somewhere else. If you don’t mind riding a moth. Hey, Gandalf booked a flight with a moth, come to think of it. (His illustration of “Grownupishness” includes the caption: Sightless, Blind, Well-Wrapped Up.)

Undertenishness, by J.R.R. Tolkien

January 2nd, 2014 by dave dorsey

When I can carve out the time soon, I’m going to write about Henry Coupe and his oils. Coupe joined Viridian Artists late last year, and we had several of his paintings sitting along the countertop behind the desk. As I was talking to our gallery sitter, I kept glancing at the paintings, wondering where they’d come from. After about an hour, I finally spoke up and was told that he’s an 89-year-old artist in Utica who has been painting and exhibiting since the 60s. The more I looked, the more I liked. So on my last drive to the city, to help hang the current show, I stopped in Utica for a few hours and met with his wife, Ann, who told me Henry entered a nursing home in the past year, thanks to a life-threatening accident when he was being tested at a local hospital. I got a chance to see somewhere in the range of three dozen of his paintings there at his house, and we visited the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, where I studied print-making when I lived in Utica and worked as a reporter at the Observer-Dispatch in the 80s. Anyway, much more when I have the time to write at length about his tremendous work.

December 27th, 2013 by dave dorsey

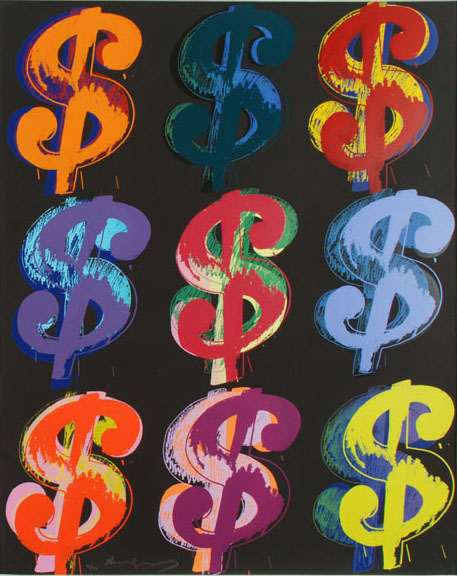

From a good piece in The New Yorker about the art market, and David Zwirner, the era’s emerging dealer-king:

“One of the reasons there’s so much talk about money is that it’s so much easier to talk about than the art,” Zwirner told me one day. You meet a lot of people in the art world who are exhausted and dismayed by the focus on money, and by its dominance. It distracts from the work, they say. It distorts curatorial instincts, critical appraisals, and young artists’ careers. It scares away civilians, who begin to lump art in with other symptoms of excess and dismiss it as another garish plaything of the rich. Of course, many of those who complain—dealers, artists, curators—are complicit. The culture industry, which supports them in one way or another, and which hardly existed a generation ago, subsists on all that money—mostly on the largesse and folly of wealthy art lovers, whether their motivations are lofty or base.

“Since the doldrums of the early nineties, the market for contemporary art, which has various definitions (work created after the Second World War, or during “our” lifetime, or post-1960, or post-1970), has rocketed up, year after year, flattening out briefly amid the financial crisis and global recession of 2008-09, before resuming its climb. Big annual returns have attracted more people to buying art, which has raised prices further. It is no coincidence that this steep rise, in recent decades, coincides with the increasing financialization of the world economy. The accumulation of greater wealth in the hands of a smaller percentage of the world’s population has created immense fortunes with a limitless capacity to pursue a limited supply of art work. The globalization of the art market—the interest in contemporary art among newly wealthy Asians, Latin Americans, Arabs, and Russians—has furnished it with scores of new buyers, and perhaps fresh supplies of greater fools. Once you have hundreds of millions of dollars, it’s hard to know where to put it all. Art is transportable, unregulated, glamorous, arcane, beautiful, difficult. It is easier to store than oil, more esoteric than diamonds, more durable than political influence. Its elusive valuation makes it conducive to extremely creative tax accounting.”

And:

“Dealers come and go, their names and enterprises soon forgotten. All that survives is the detritus of their influence and taste—what they sold and whom they sold it to. The biggest dealers are like Ice Age mega-glaciers, leaving behind vast moraines of art work they’d borne aloft and finally deposited in mansions and museums before melting away.”

December 25th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Green Wheat Fields, Auvers, 1890

I’d thought Wheat Field with Crows had that honor, but apparently this largely unseen painting might have been his goodbye. It’s as good as anything from that final year. Another reason to visit the National Gallery again.

Van Gogh scholars are likely to be thrilled that the work is once again in the public domain. The painting has not been displayed publicly since 1966. Mellon’s wife, Rachel Lambert Mellon, has held the rights to the painting since his death in 1999. This year, she relinquished the remainder of her estate, allowing the museum to display the work. Until recently, the painting hung over the fireplace in the Mellons’ Upperville, Va., home.

Washington Post

December 23rd, 2013 by dave dorsey

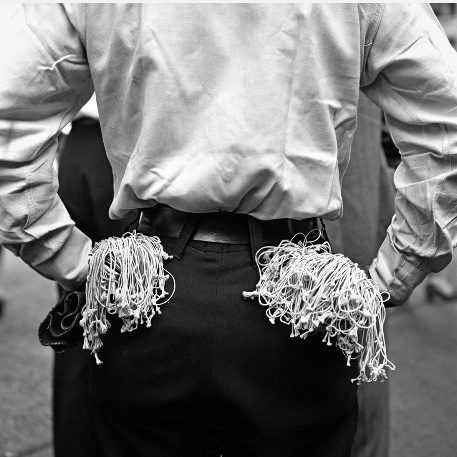

September, 1959, Vivian Maier

A semi-snarky, dismissive essay from The Atlantic about an incredibly gifted photographer suggests that her story, as an outsider–rather than the quality of the work–has captured the imagination of people who love Vivian Maier’s photography. Formal mastery combined with the timing and luck to capture a living, breathing moment, and a fascination and empathy that drove her to capture compelling images of other human beings, and quite a few of herself. That’s Vivian Maier. This is a critic who questions Maier’s rank as an artist but wrote not too long ago: “Selfies are Art.” So which is it? She did quite a few “selfies.” Maybe those are “high art,” which is a term that pops up in the quote below. (Clemente Greenberg called. He wants his vocabulary back.) The only time I’ve been able to tolerate the term “high art” was when it was the title of a movie by Lisa Cholodenko, which, come to think of it, was about a character based on Nan Goldin, whose celebrated photographs have the same kind of spontaneity and everydayness and low-ness, for that matter, as Maier’s, but with more shock value (back in the day, anyway.) Stick ’em in the scrapbook! Anybody who was there could have taken them, right? Which is more applicable to Goldin than Maier’s shots, which are more rigorous, in formal terms.

The film does not use the term “outsider artist,” but Maier does not appear to have had any formal training and didn’t show in galleries during her lifetime. In part this may have reflected her own individual preferences or difficulties; she was by many accounts a temperamental, private person, and seems to have struggled with mental illness late in life. In part, her distance from the high art world was probably because she was working-class. Many of her pictures are of the children who were in her care; they show kids at the beach climbing over rocks, children happy, children sad. If those sound like your typical family photos, well, they are.

–Noah Berlatsky

December 21st, 2013 by dave dorsey

New figure paintings from Sarah F. Burnes.

New figure paintings from Sarah F. Burnes.

December 19th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Girl in Black Vest, Susan Sills

Once Upon a Time, the holiday show for members and guests, is opening tonight at Viridian Artists. Above, one of the pieces in the show, a drawing that I’m willing to bet is Susan Sills herself, once upon a time. From our website:

Viridian Artists is pleased to present “Once Upon A Time” an exhibition of Viridian Artists & Friends, December 17th to January 11th, 2014 at 548 West 28thStreet, also accessible from 547 W 27th Street. There will be an opening reception Thursday December 19th, 6-8PM. In addition, Viridian is bringing back Ye Olde Art Shoppe of art cards, prints, books, and other artist-made gifts available for under $99, so that everyone has a chance to do some last minute holiday gift shopping.

Each year, in a spirit of holiday giving and sharing, Viridian Artists takes time to share the spirit of the holidays by inviting guest artists to show their creations along with us. Dress festively & come join us on Thursday, December 19th to celebrate and remember how things were “Once Upon A Time”.

Once upon a Time

there was a pay phone on every corner & you could make a call for a quarter

children were spanked when they disobeyed the teacher

business lunches were 2 martinis

we didn’t kiss ’til the third date

we could go to Europe on $5 a Day

we wore backpacks only when we went camping

we could have a delicious lunch for $5

the frame was not more important than the picture

women didn’t dream of becoming President

only men wore the pants in the family

we used to write each other letters in script & mail them at the post office…

we could have a cigarette with our drink

we did our grocery shopping on Saturday, etc, etc…

Janet Bohman, Renee Borkow, Henry Coupe, May DeViney, David Dorsey, Arthur Dworin, Bernice Faegenburg, Tazuko Fujii, Alan Gaynor, Wally Gilbert, Joshua Greenberg, Elizabeth Featherstone Hoff, Renee Kahn, Kathleen King, Valerii Klymchuk, Namiyo Kubo, Elvira Lantenhammer, Nancy Macina, Jeffrey Melzack, Matthias Merdan, Michael Miller, Stacey Clarfield Newman, Oi Sawa, Barbara K Schwartz, Susan Sills, Virginia Evans Smit, Angela Smith, Robert Smith, Sheila Smith, Deborah Sudran, Bob Tomlinson, Meredeth Turshen,

With Guest Artists: Adrienne Ankuda, Barrett Benton, Richard Brachman, Benjamin Briggs, Robert Cenendella, Ursula Clark, Lee Cordray, Gloria Cunnick, Abby DuBow, Phyllis Featherstone, Flashlight & Bill Rabinovitch, Celia Gilbert, Elizabeth Ginsberg, Brenda Hernandez, Jacqui Joseph, Mary Frances Judge, Jae Young Kim, Minjung Kim, Angela LaMonte, John Lloyd, Marcia Lloyd, Dee Dee Maguire, Bob Marvin, Robert Mielenhausen, Barbara Minsky, Darryl Moody, Eileen Mullan, Vernita N’Cognita, Sunanda Parikh, Shirley Pasternak, Lauren Purje, William Rodwell, Joseph J Roy, Leonard Rosenfeld, Stephen Salek, Jane Talcott, Daniel Victor, Vicky Wojcik