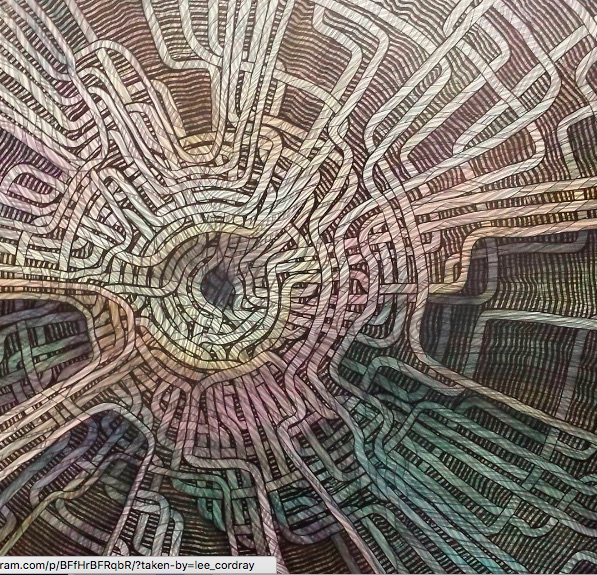

Gary Lee Cordray

From his Instagram.

the painting life

Takeaway: Respect Vermeer above all. And do whatever they are saying can’t be done anymore. From Chuck Close profile today in the Times magazine:

Even as you slip forward a few years and he begins adding color in the early 1970s, you’ll find no painterly style on the canvas, no distinctive brushwork — namely because he had given up brushes to work with a paint sprayer, which he considered a homage to Vermeer. “I can figure out how any painting in the history of art got made, with the exception of Vermeer’s,” he told me. “It’s like a divine wind blew the pigment on.”

Remember that Close was making these portraits at a time of spectacular upheaval in American art, when many of his contemporaries were preoccupied with wild, experimental work — with artists like Walter de Maria, Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson moving into the desert, where they would trap lightning, build a mile-long city of black stone and extend a huge spiral walkway into the Great Salt Lake. Just a few years earlier, the prominent critic Clement Greenberg effectively banished the kind of work that Close was doing from the ranks of modern art. “With an advanced artist,” Greenberg wrote, “it’s now not possible to make a portrait.” So in the world that Close inhabited, his work presented a strange duality. In one sense, the decision to paint photographic portraiture was almost laughably conventional. In another, it was among the most defiant things a downtown artist could do . . .

I was having an email conversation with a good friend (and a couple others, including my brother) on the need, or lack of it, for historical accuracy in movies based on actual events. My friend’s position was that art can do anything it likes, as long as it conveys eternal and absolute human values. I’ve been reading Heidegger’s later lectures over the past year—I’m going to offer much more of my thoughts on those in the near future, I hope—where the idea of “values,” comes under repeated assault, in interesting ways. Yet, as penetrating and surprisingly accessible as Heidegger is in these essays, I tend to agree with my friend, not Heidegger, that in the moral realm, certain things are unassailable and unchanging. (Heidegger’s interest was never ethics, which is why he’s compelling, but more on that later.) Yet, those eternal “values” or “truths” my friend advocates are like Kafka’s castle, partly visible from down here in the village, but its hard to find a permanent home in them–and often difficult to connect that realm with the complexity of human obligations down here on the street.

My friend’s position is that movies need to embody moral truth in order to be worthwhile, and any viewing time devoted to films of lesser quality is not just a waste of attention but destructive. TV should come with a surgeon general’s warning. I informed him that, right or not, he would be able to pry my vintage DVDs of The Simpsons from my fingers only when said fingers are cold and dead. (Actually I cited Rocky and Bullwinkle.) He was unmoved. But he insists, as always, that movies can be utterly unpleasant to watch—the equivalent of eating your broccoli—and yet be essential to the life of the mind. Last Year at Marienbad? Really? Dave Hickey became notorious as an articulate opponent of this view in his celebration of the essential need for beauty in art. His position, as I understand it, is: Give me pleasure or move along—because without it, I’m not going to pay attention to your precious truths. I second that. And I believe Hickey was suggesting that beauty keeps generating truth in different ways as time passes, for succeeding generations, all on its own, without a premeditated effort to adhere to some preconception of “truth” prior to its creation. Its creation becomes a source of unexpected truth, not an illustration of something already known. (This is actually closer to Heidegger’s outlook, I suspect.)

My friend insists that we ignore certain annoying or unpleasant expressions of truth in films at our peril. As much as I disagree with his general stance on this, and think that a movie ought to be engaging and at some level enjoyable to watch, no matter how uncompromisingly true it is, I wasn’t going to engage him on this. I’ve learned not to do that. Yet, along with Hickey, I think this attitude, in part, has made visual art the sort of isolated, segregated, boutique activity most people consider it to be now—a branch of the arts, in general, created only for the discerning, initiated elite while being irrelevant to most people’s lives. As I put it to my good friend: “My position on all this is to ask, if a tree falls in a forest and no one bothers to listen, does it matter whether or not it makes a sound?”

Onion on a Carved Table, oil on linen

Jim and Ginny Hall’s Oxford Gallery has been selling a lot of my work over the past two years. When I got back from our visit to California this month, I found a check for this one waiting for me. He’d included it in the gallery’s summer show.

From Jason Franz at Manifest Gallery about one of the worthiest opportunities for artists who want to get their work seen:

It is the 7th INPA I’m writing about today…

If you have not already done so, I would like to encourage you to consider submitting your work to the 7th International Painting Annual which has the upcoming (final) deadline of July 24th.

As you may recall, within the past few years we doubled the cash awards for all three of our book projects—with each now offering a $1200 first prize. We do everything with our fellow artists in mind (we’re artists, students, and professors too!), and so we are very happy when our board of directors approves an increase in what we can give back. Believe me, we know that every little bit helps. (We also increased the Manifest Prize to $5000!).

Remember, our non-profit publications are undertaken in an effort to allow wider participation by artists from farther away since they do not require the physical work be available or shipped. The books also enable our otherwise gallery-bound exhibition program to reach a wider viewing audience because books can easily be shipped anywhere.

Many academic libraries collect our publications and college professors (perhaps many of you!) use our books in the classroom as prime examples of the diversity of types of works being made around the world by artists their students can relate to. The fact that we refresh this collection every year makes the resulting compendium even more valuable for everyone.

It is very important for you to know that your past participation does not hinder nor help your submission to this or future projects. As you surely know by now, Manifest’s juries are shuffled each project, and juries are ‘blind’ in that they are not aware of whose work they’re viewing. Your identity is not a criteria. That said, you’ve had success in the past, and this is a good sign that your work has what it takes to win approval through the Manifest jury process. That fact should be encouraging.

So, because we want this 7th volume to continue the series’ participation level and growth in quality and diversity of painting, I wanted to encourage you to submit your work, and to share the opportunity with others if you would.

You can get the details here: www.manifestgallery.org/inpa7

Please don’t hesitate to email me if you have any questions. And thanks again for being a part of Manifest’s history! I hope to see your work again soon.

Jason Franz

Executive Director

It’s always gratifying to see a painting find its way to a warm and loving environment. I was invited to the birthday party of one of my most devoted collectors here in Rochester a couple weeks ago. She owns two of my paintings, including this large one, Mangoes and Matthiasdottir, which won an award in an exhibition at the Memorial Art Gallery. She purchased it from that show in 2009 and recently moved to this new apartment and wanted me to see the work in its new spot. Lest anyone get the impression I’m completely self-absorbed, and not just mostly self-absorbed, I should point out how great it was to see her again and meet her friends and children.

It’s always gratifying to see a painting find its way to a warm and loving environment. I was invited to the birthday party of one of my most devoted collectors here in Rochester a couple weeks ago. She owns two of my paintings, including this large one, Mangoes and Matthiasdottir, which won an award in an exhibition at the Memorial Art Gallery. She purchased it from that show in 2009 and recently moved to this new apartment and wanted me to see the work in its new spot. Lest anyone get the impression I’m completely self-absorbed, and not just mostly self-absorbed, I should point out how great it was to see her again and meet her friends and children.

This is a detail from Muente’s perfectly composed painting, from INPA 5, Manifest International Painting Annual, Manifest Gallery. Manifest’s current selection process involves a complex two-part system, juried by a 9-12 member panel of professional and academic volunteer advisors with a broad range of expertise. The jury then passes along their scores to the project curator who will assemble the final selections from the jury-approved pool. The gallery is accepting entries for the next annual, with a deadline of July 18.

One of Bill Santelli’s tremendous drawings has been selected for “DRAWING NEVER DIES” a national juried exhibition at Redline Contemporary Arts Center, Denver, CO. This drawing comes from a series I’ve loved since I first saw it here at Oxford Gallery.

The exhibition will run from July 9 – August 5, 2016. Opening Reception is July 9, 2016 at 6PM.

Bill’s contribution to the show is THE PATH 29, above, a prismacolor pencil drawing.

About the Exhibition, from Redline:

Perhaps the oldest and most basic art act, drawing remains relevant despite significant changes in technology and the nature of art. The definition of drawing is blurry and often serves as a basis for study in most every other medium. Drawing is rarely is given the same attention as other disciplines within visual art, but is regularly a root for other artistic practices, as well as being a valid realm on its own.

Drawing Never Dies will survey the range of drawing taking place today. Approaches may span from minimal to maximal, meticulous to messy, monumental to miniature. From commonplace and traditional materials such as graphite and pens on paper, to drawing on the surface of the earth, to artists working with technology such as 3d pen drawings in space or forms intended for experience on the screen; we are interested in a broad/expansive survey of drawing now.

That’s Rule #6 from William Friedkin in this interesting interview:

Inside every one of us who has ever created anything there is almost a constant record of failure, that’s what we think of, that’s what involves our thought process. I know some of the most successful filmmakers and songwriters and inside these giant talents is a little mouse. And that is, I guess, the problem of the creative artist.

I’m hardly posting here of late, because I’m finally hitting my stride again in the studio, after a desultory year, crammed with more social activity and other work than any year in recent memory–all of it good, but also a hindrance to daily painting. I have been almost completely abstaining from exhibiting work this year in an effort to get to the point I think I’m reaching now in my work, with strong momentum, along with a queue of ideas for enough future paintings to fill a show and a currently-successful diagonal move toward something a little different in my still lifes–while continuing to do what I’ve done before, alternating between the two modes. The perfectly executed painting by Porter, above, serves as something of an inspiration–most of the work he did at the end of his life (he had four years left when he painted this one) humbles me, actually, though what I’m doing isn’t nearly as loose. I may get there. What I’m trying to uphold from his example is the sense of a light-drenched scene, where color and only the upper register of values are used to define form, where the shape of the paint is as important as whatever the paint depicts, and where everything seems to have been laid down with a single brush, giving a unity to the marks. It’s as spontaneous as a watercolor, the liquid quality of the oil conveying the shine and reflections of the sunlight. It looks exactly right as you see it for the first time, until you wonder why the shadows of the porch’s window frames could be that yellowish-ochre-orange: in fact it’s the color of the table revealing itself in the shadows of those wooden struts, apparently beneath a sheet of glass laid down over it, or simply a glossy finish on the wooden tabletop. It appears Porter applied that color to the entire tabletop and then went back over it, alla prima, or else on the next day, with an off-white to convey the reflected light from outside. Maybe it’s just an arbitrary color choice that works because it evokes all of this even if he didn’t see it on the actual table. This one has an effortless quality, sprezzatura, the masterful way all the colors harmonize as an abstract pattern, and yet also, amazingly, evoke the unified world of that hazy day on the Maine coast, instantly recognizable as a moment of ordinary happiness, perfection. But it’s the quality of this light, coming from behind but also glowing in this porch, seemingly from all directions, that pushes me to take a different approach in the painting I’m doing now, not just in the quality of the scene, but in the way I’m applying the paint–a greater simplicity of application, thicker layers, some wet-on-wet, and a bolder more simplified way of building the picture through areas of color with less attention to minute details. I’m liking it.

Oh, snap: “That dull Merchant-Ivory movie ‘Surviving Picasso’ has been much criticized for showing, for legal reasons, only ‘faked’ paintings of Picasso’s work in the forties and fifties, but no one has had quite the courage to say that it’s hard to tell them from the real ones, except that Picasso’s real ones of the time were even worse.”

–Adam Gopnik, “Escaping Picasso,” 1996, The New Yorker

I’m happily painting every day again, to the neglect of other things, such as writing about painting. But I want to pass along a series of examples from the INPA 5, the latest international painting annual from Manifest Gallery. This detail, slightly cropped at the right edge, is of a painting done by David Smith, one of my favorite artists who exhibits regularly at Manifest in Cincinnati. He combines the subject and feel of classic Chinese scroll painting–misty camel-hump mountains–in a contemporary mode. Instead of water-based paint on paper, he’s using oil on plywood, and the integral role of the brushwork in traditional Chinese painting here has a gestural quality that reminds me of Richter’s abstraction. And yet it works perfectly to evoke nearly the same kind of world a Song dynasty painter-poet would have evoked. Would love to know more about Smith, how and why he paints in Hong Kong, and if he was born there or is an expatriate.

I’ve been talking with some other artists lately about the motivation to make art–and how easy it can be to lose the intrinsic urge to make it by focusing on it as a means rather than an end. If you aren’t selling anything at the moment, or no one seems to be paying much attention, then it’s tempting to go outside and, say, plant some vegetables rather than struggle with a resistant picture. Art is hard work, but I do it mostly because it’s so pleasurable to finish a painting, and sometimes even more so if the image played hard to get. It’s easy to drift away from that zone where the effort is both constraining but also feels good, the reward of pushing back against a challenge, with the sequence of the hundreds of interim completions along the way toward being done. When it’s most frustrating, it’s easy to dismiss what Keats said about poetry: “If Poetry comes not as naturally as Leaves to a tree it had better not come at all.” But I doubt that he meant all good creative work has to be a first draft: Kerouac, non-stop with his long scroll of paper, or Edwin Dickinson with his premier coup work. I think what he meant was that the urge to create something comes naturally, and that’s why people do it, with no other purpose in mind. It’s an end in itself: which is what the “fine” in fine art really means, fin, the end.

I had coffee yesterday with a young artist, Adam LaPorta, who also sells Piction software to art museums. He sat down with me, Bill Stephens and Bill Santelli, for a casual conversation about how technology has changed MORE

An interesting two-artist show opens this week at Patricia O’Keefe Ross Art Gallery at St. John Fisher College, with a reception Thursday evening. Entitled “Where Two Women and Nature Converge” it features new work from Jean K. Stephens and Raphaela McCormack. I’m familiar with Jean’s work from exhibitions at Oxford Gallery, and have always loved her nests and the less frequent skulls she does. This show also features images based on still lifes she has assembled from various materials–natural and human–many of them in the shape of female figures. McCormack assembles sturdy-looking but delicate urns, vessels and images of sailing ships from natural materials. Both artists honor the physical qualities of the materials they gather and shape in the process of creating an image that has human resonance–without obscuring the actual nature of what you’re seeing.

On the heels of my visit to New York to see contemporary interpretations of Medusa and Pandora at Danese Corey, I recently toured Oxford Gallery’s Myth’s and Mythologies. The invitation to this themed group show went out half a year ago and the results are thought-provoking, rewarding, and occasionally stunning, built around various interpretations of mythological figures as well as modern “myths” begging to be busted—the glory of motherhood, in one case, and “trickle-down economics” in another. In other words, there’s a little something for everyone. It ranges from an astonishingly beautiful example of classical sculpture in cararra marble from Italy to a minimalist abstraction painted on a metal panel. A small figure of Daphne, carved by Dario Tazzioli at his studio in Italy, has already been sold—the highest priced piece in the exhibit. It’s easy to see why: astonishingly well done, the female figure seeming to reach up and dissolve into a filigree of roots and branches around her head so delicate that it’s hard to imagine how the sculptor did it. It’s a rare example of centuries-old artistry done by someone trained in Renaissance techniques, using the kind of marble Michelangelo used and a bow drill—reason alone to visit the show. At the other end of the spectrum is Ryan Schroeder’s “Trickle Down Economics,” a large, vigorously executed oil showing the half-demolished interior of an abandoned building, with what appears to be a sinkhole almost underfoot—overall a sardonic reflection on how one man’s ceiling is another one’s floor, economically speaking.

Most of the work relies on traditional mythology. Icarus gets a lot of attention here, as does Persephone, as well as a crew of other Greek or Roman figures: Medusa, Pluto, Neptune, Pandora, Romulus and Remus, Cupid and Psyche, and Pegasus. But the subjects are wide-ranging and the artists find clever ways to put a mythical spin MORE

I woke up at 1:15 a couple nights ago and couldn’t get back to sleep until around 2:30, which has been my sleep pattern for years, but while I tossed and turned, my thoughts came together on Matisse, whose work and life I’ve been studying intermittently for half a year now. It occurred to me that he knew exactly what he was doing when he wrote the famous line in 1908, a year after Picasso’s outrageous Demoiselles D’Avignon was painted, and this short passage of prose probably relegated Matisse to a back seat, in comparison to Picasso, with critics and historians ever since. (Do a search for the many biographies of Picasso and then try Matisse. Incredibly, as far as I can tell, only one biography has been written of Matisse, and it was published only a decade ago.) I came across his personal declaration of independence again yesterday reading Matisse on Art:

What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, an art that could be for every mental worker, for the businessman as well as the man of letters, for example, a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair that provides relaxation from fatigue.

Imagine the derision this remark must have inspired from all quarters, and still probably does even now in the Age of Koons, especially over his “devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter.” From the point of view of those who saw art as a continuous shocking overthrow of prevailing artistic norms—modernism’s hollow legacy—this sentence sounds like blasphemy and backsliding, or worse. I think, in reality, it was a way of taking a stance against history, in a way. Matisse knew the risk he was taking, that he was setting himself at odds with the elements and theories he expected to be most celebrated in painting as it emerged in the 20th century. He asserts that he’s painting for the middle class, the businessman, the ordinary art lover, the loathed bourgeoisie—all of the people modernism was trying to outrage and unsettle and disturb. Instead, like Van Gogh, MORE

I’ve gotten back to a schedule of daily painting, and it makes a difference. When you get pulled away from painting for periods of time, it takes awhile to regain momentum and also to restore a sense of confidence in balancing the freedom of making intuitive, felt choices—taking chances to see what will happen—against an adherence to predictable craft, what you know paint will do from years of working with it. Which is obedience: to what you see, and what you know you need to do. If you go too far toward freedom, or you surrender completely to a routine of reliable labor, the soul of the painting slips away, or else it just becomes a mess.

So far, since I’ve been able to resume working every day, I’ve stuck to a series of smaller paintings of patterned bowls in order to focus more on the surface and the paint, less on producing an exact replica of what I see. I’m giving myself more room to improvise with color, and the way I’m setting up each still life it’s easier for me to see the flat pattern of shapes and color in an abstract way. I’m trying to increase the tension between representation and visible marks. I told Bill Santelli recently that I’m attempting to use a thicker application of paint, but afterward I realized that wasn’t entirely right: in places I’m letting bits of canvas show through, so the paint’s actually non-existent in those spots—one can’t get any thinner than that. But when I’m applying the paint, more often its consistency is closer to its original viscosity out of the tube. It’s thick where it needs to be and thin where it needs to be, that’s all, but overall a little heavier than in the past. I want the paint to be visible, as paint, as much as possible. I’m also trying to simplify the areas of color, and value, striving for the ability to depict more with less brushwork, while leaving more evidence of my hand and the brush. I’ve done all of these things in the past, intermittently, and then returned to the more finished, highly detailed realism of most work I usually sell. (I plan to alternate between both modes now.) Paintings I’ve done this way have sold, as well, so marketability isn’t the calculation I’m making. In this series, I want paintings that evoke more while specifying less, that’s all. And if I succeed, I may be able to apply what I’m learning in more and more ways.

When I was in Manhattan to see Suzie MacMurray’s show, I put in a day touring a dozen other galleries, and saw Alyssa Monks’ new paintings at Forum. She seems to be trying to break away from the photorealism she’s been known for—and it’s giving her a path toward a much more varied palette, looser application of paint, and images that are much less about the way the physical world looks and seem closer to a psychological depiction of an inner world. It’s a move away from the urge to astonish with technical skill toward something more felt and elusive and hard to pin down. Still, I wanted them to be even more abstract, looser and ambiguous—in reality they may simply be straightforward depictions of a beautiful face seen through a window that reflects a wooded tract behind the viewer. (A new take on her faces seen through water, only this time the water is still and reflective.) But her focus on color and the more painterly technique seems as if it might lead to something even more interesting. And I learned Arcadia, one of my favorite galleries, has moved to Santa Monica. I was disappointed not to be able to pay a visit, but it’s now located on the same street where my son and daughter-in-law live–which will be mighty convenient in July.

Manifest Creative Research Gallery and Drawing Center has shipped its fifth International Painting Annual, which arrived here last week. As usual, it’s full of treasures from artists who made the cut from the around the world. The gallery received 1,475 submissions: 434 artists from 44 states and 20 countries submitted to INPA 5 and out of those artists, only 69 were chosen. For a select few, Manifest choose several pieces for inclusion, offering a clear sense of that artist’s stylistic continuity from one work to the next. The honor was fully deserved in the case of the lucky few. It’s a joy to see the diversity and vitality of work, some of it technically astonishing, from painters located in places as far-flung as Hong Kong, Kentucky, Germany and Scotland. I’ll post some of the work that impressed me the most over the next couple weeks. There are some real gems.

Manifest Creative Research Gallery and Drawing Center has shipped its fifth International Painting Annual, which arrived here last week. As usual, it’s full of treasures from artists who made the cut from the around the world. The gallery received 1,475 submissions: 434 artists from 44 states and 20 countries submitted to INPA 5 and out of those artists, only 69 were chosen. For a select few, Manifest choose several pieces for inclusion, offering a clear sense of that artist’s stylistic continuity from one work to the next. The honor was fully deserved in the case of the lucky few. It’s a joy to see the diversity and vitality of work, some of it technically astonishing, from painters located in places as far-flung as Hong Kong, Kentucky, Germany and Scotland. I’ll post some of the work that impressed me the most over the next couple weeks. There are some real gems.

A fascinating new invitational group show is up at Oxford, on the theme of myths. I got an early look at some of the work while it was going up last week, on a visit with Bill Santelli and Bill Stephens. A wide range of media and subjects, some distinct interpretations of familiar myths, others tangentially related to a broader definition of mythology. The opening on Saturday evening should be fun.