Archive Page 40

August 25th, 2013 by dave dorsey

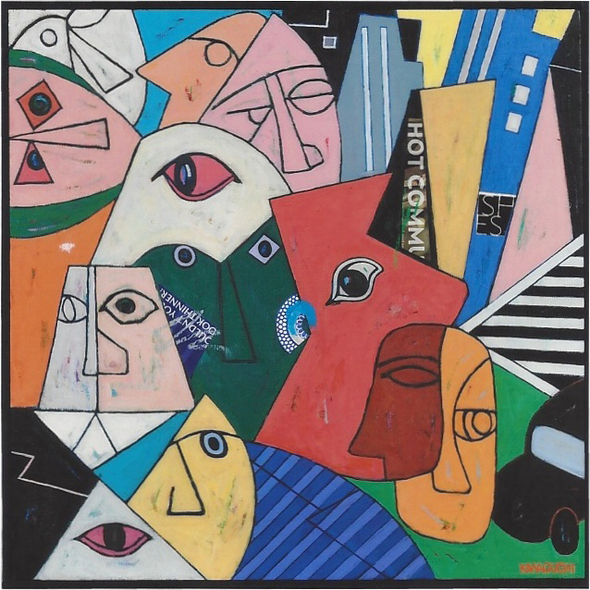

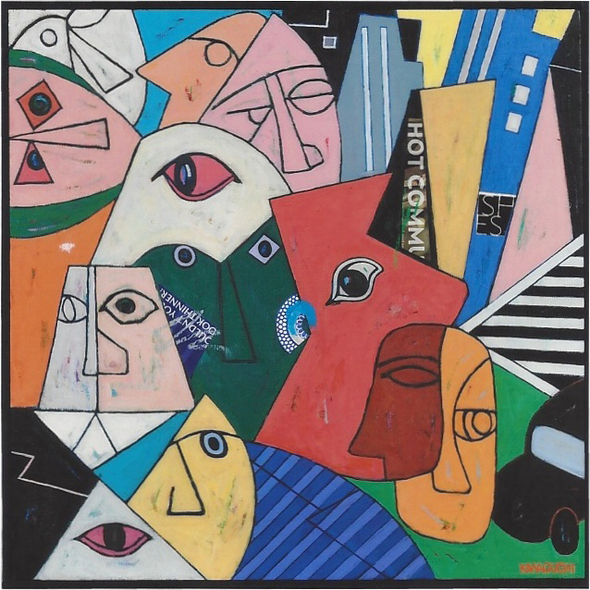

In a week or so, Kiyoshi Kawaguchi returns to Viridian Artists with a show of recent work about urban life that lives somewhere on a spectrum that includes both Ben Shahn and Stuart Davis. He’s exhibited at Viridian in 1978 and again in 2010. Like an elbow-to-shoulder subway ride, his images are busy and packed with life, but also quietly sad and solitary. The lonely crowd in Tokyo looks remarkably like the one in Manhattan. The artist’s contiguous faces seem isolated and mute, and yet they fit snugly, perfectly together like fragments of a child’s easy jigsaw puzzle. All those seemingly autonomous figures create a unified, interdependent whole. It’s how art, and life, work. (When they do. ) It’ll be going up next weekend and runs until Sept. 28, when it will head back for a show in Tokyo. I hope I can get time to talk with him while he’s here.

“Kawaguchi captures the exuberance and complex rhythms of city life with simple geometry and vibrant color. Kawaguchi paints bright pictures of a hyperlinked humankind full of possibilities, including being tangled by its own connections.”

–Deirdre S. Greben, former managing editor ARTnews

“Kiyoshi Kawaguchi …synthesizes classical American 30′s and 40′s traditionalism with Japanese modern day technology and craziness of city life… While other artists ignore the world situation and brand their works with Louie Vuitton, Kawaguchi foresees the future and tells it through his cryptic paintings.”

–Walter Wickiser, of Walter Wickiser Gallery, Inc

August 23rd, 2013 by dave dorsey

If only all of Fischl’s work were this good.

Eric Fischl: “Back then you could be shown in museums around the world and still be doing a teaching job or driving a taxi or something to do it . . . “ Things haven’t changed all that much except for the one percent, have they?

Some interesting talk with Alec Baldwin on how Fischl’s father learned to communicate with his son by taking up art himself:

Eric Fischl: My father . . . actually didn’t understand what success was in art anyway. He’d kinda given up by then, right? So in . . .

Alec Baldwin: On what? Understanding you?

Eric Fischl: On me. Yeah, exactly . . . he really didn’t know anything about art so he didn’t really know anything about what success in art was. And back then success and fortune were not connected to each other in the art world. You could be highly successful, you know, shown in museums around the world and still be doing a teaching job or driving a taxi or something to do it.

So he was perplexed that I would even be in a field in which there wasn’t a monetary reward, necessarily, right? But at some point, he started to see my name in print. And that was something that he understood as success.

All of a sudden a local newspaper or an art magazine or something, there’s his son, right? And then he really flipped from sort of disengagement to the proud parent who – we’d go into a grocery store and at the checkout counter, he’d go, ‘You know who this is? My son. This is the artist.’

Alec Baldwin: He’d take the clipping out of his wallet.

Eric Fischl: [Laughter] Yeah, exactly.

Alec Baldwin: ‘This is from The New York Times. My little E-R-I-C F-I-S-C-H-L’ – no E-L.

Eric Fischl: No E. No E. Well, you know he –

Eric Fischl: He became an artist at the end of his life as well. He discovered collage, and it took him a while after he retired to – he tried other things and then all of a sudden, he found himself, sitting in his office at home, cutting pictures out and gluing them together. You know, he was not a schooled artist but he had an eye and he had a kind of liveliness to these collages that he made that were very expressive.

And by the time he died, I’d realized that he and I could never talk to each other. We just kept missing, you know? But we understood each other visually, and so he would send me his collages and I knew exactly what he was thinking about, where he was at, how he was feeling. He was really communicating through these visual images.

And he showed me that he was – had been using my paintings to understand what had happened in our lives with my mother and the whole family dynamic. And so we, actually, were both visual people who understood what that meant to communicate visually to each other. So it was deeply rewarding to me ultimately, but it took me a while to understand it.

August 20th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Our director at Viridian Artists, Vernita Nemec, is offering a performance workshop in Germany. Details here.

August 19th, 2013 by dave dorsey

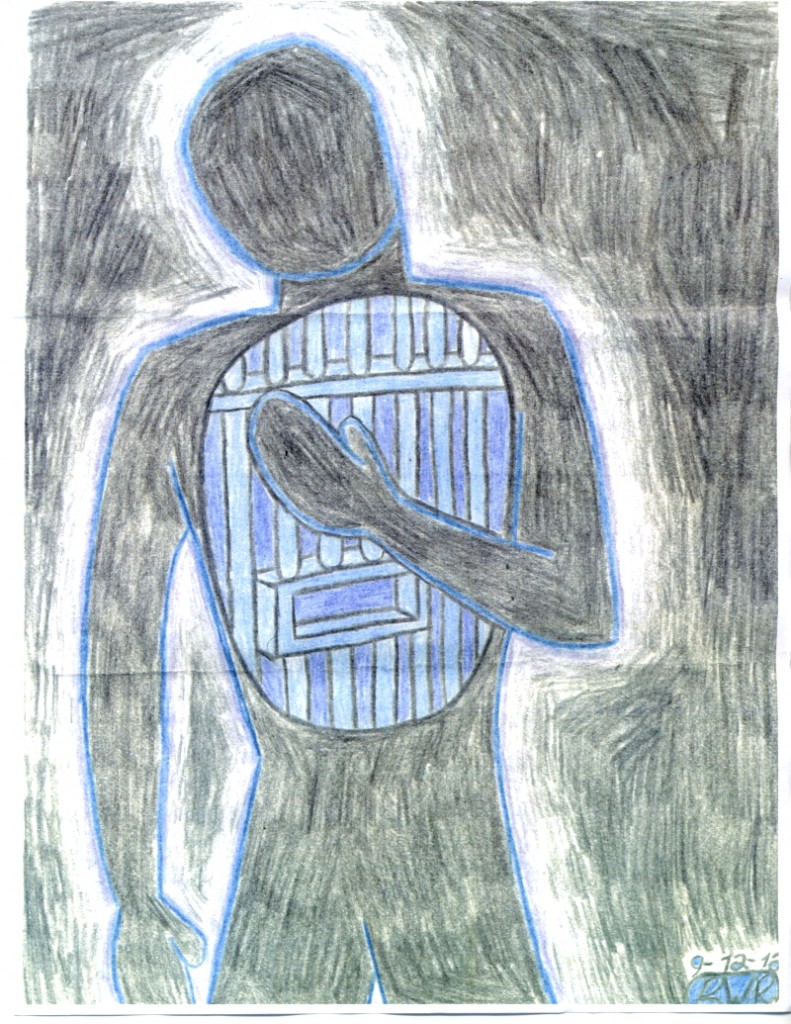

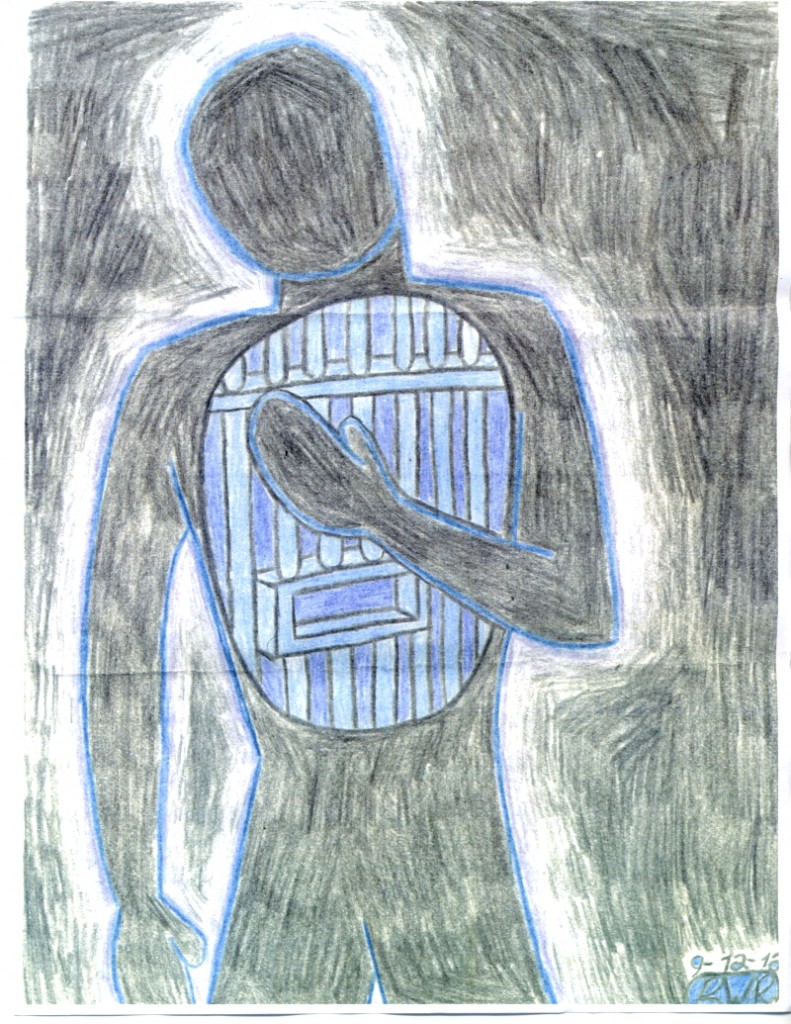

“Eventually I was moved to a cell with the same view, but with overgrown weeds outside. They became the epitome of beauty to me. They were “my weeds.” Had someone gone out and cut them, I’d have had a mental breakdown. Later on they moved us to cells (with the same nonexistent view) in another cell block, but I was confident because I knew “my weeds” were still there where we had left them.” —Brogan Rafferty

“Eventually I was moved to a cell with the same view, but with overgrown weeds outside. They became the epitome of beauty to me. They were “my weeds.” Had someone gone out and cut them, I’d have had a mental breakdown. Later on they moved us to cells (with the same nonexistent view) in another cell block, but I was confident because I knew “my weeds” were still there where we had left them.” —Brogan Rafferty

August 12th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Neil Young gives cupcake haters the stink eye.

One of the hardest balancing acts for anyone who has found any sort of market for creative work is how much to keep pursuing work that has a chance of selling. In other words, how much should anyone purposely create work that is likely to sell, simply because it will sell. That last phrase is crucial. Part of what this activity involves is forgetting the wisdom of Yogi Berra, which was the content of my previous post. Doing great work means taking on a challenge where what you know how to do isn’t enough–at some point it doesn’t avail. When money beckons, the temptation is to settle into routines you do know, and though the results may be desirable to a buyer, the artist who’s honest knows that something lifeless has been passed along. (What’s so distinctive about painting for me is how it requires me to do things I don’t know how to do, and how the act of painting, like a golf swing, involves things that can’t be stored away as knowledge. The learning, if it’s there at all, happens in your body and your subconscious. Painting well is more about unknowing.) I’ve been finishing up a commissioned painting, a second version of a painting I sold several years ago–at the request of a family member who wants to buy it. I got this request early this year and have been procrastinating for months, partly in the interest of completing work I wanted to enter in the Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition this year, but also because I wasn’t sure I wanted to put in the weeks required to complete what will be nearly a duplicate of a previous painting. With my other work done, I had a choice between doing this repeat performance or creating a series of smaller paintings, which I have also been postponing for well over a year as well. (There’s a lot of procrastination up in here at Casa Dorsey. . .)

Walt Thomas, a friend who sends links to stories that occasionally inspire my posts, emailed me a link to this story about how David Geffen once sued Neil Young for not trying hard enough to be Neil Young. He’d started recording music MORE

August 10th, 2013 by dave dorsey

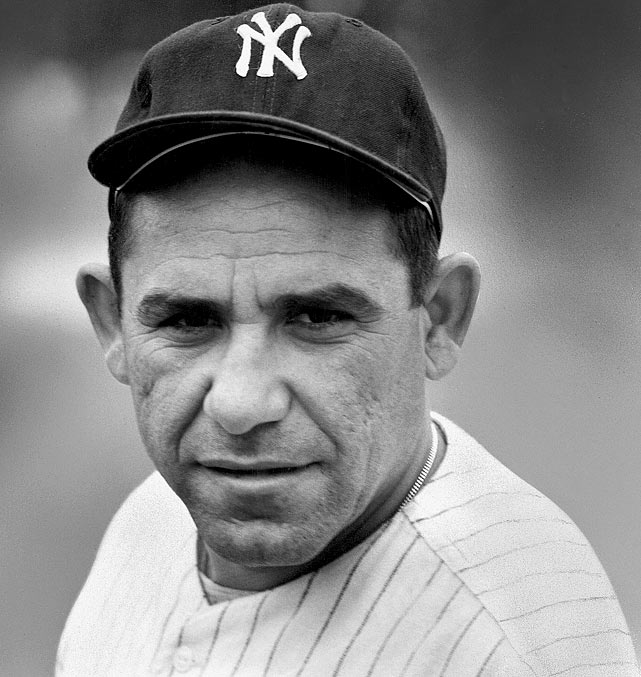

In baseball, you don't know nothing.

--Yogi Berra

Go Jason Dufner . . .

In baseball, you don't know nothing.

--Yogi Berra

Go Jason Dufner . . .

August 7th, 2013 by dave dorsey

A few days ago, I came across a clipping I found, if I remember properly, in the Sunday Times magazine, about four years ago. It’s an ad for a fashion site that baffles me (click to it and figure it out at your leisure), but I was so impressed with the paintings in this ad, I cut it out and saved it. It shows a grid of oil self-portraits, in the manner of Warhol—same pose, same face, same hat, over and over, stacked and aligned like window panes. And yet that’s where the uniformity disappears. Where Warhol would have simply reprinted the same photograph, over and over, but used as a template for different colors, this artist had painstakingly repainted his own face, wearing the same colorful stocking cap, but using different colors, with different backgrounds, different jackets, differentiating each one to the point where it was almost entirely original in comparison with all the others. And you get the same sense of repetition, mass production, but he’s reversed the tension, emphasizing the originality, stressing how much manual labor went into this repetitive act of portraiture, with the hint of mass production an almost sardonic glance back at the intentional emptiness of Pop. I love these paintings, nearly Fauvist, but closer to actual effects of light, with an emphasis on color for its own sake, even though the faces convey exactly what portraits should: a complex inner life, and the evidence of a life lived in a unique way.

Here’s what pleases me most about this image, now that I’ve accidentally stumbled upon it in my studio. These paintings are by a virtually unknown Danish artist, who died in 2008, a year before this ad appeared. His name is Borge Jensen. If you try searching for anything about him on the Web, you eventually come across two websites that reproduce the ad I’ve got in paper form, but mostly your search engine tries to correct your spelling or takes you to links about other people entirely. If you are lucky, and try enough combinations of his name with the words “artist” or “painting” you may get to this link at lauritz.com. Twice when I clicked to it, a paragraph appeared which was, in Danish, a summary of the painter’s life, but whenever I click now, it redirects me to an error page. It’s as if even the Internet wants to keep this guy unknown. I’m not sure he would mind, frankly. One of the times my browser managed to get a purchase on that site and stay on it, I had Google translate it, and this is what I got:

Børge Jensen was a painter, draftsman and printmaker – has worked with landscapes, still lifes, portraits and self-portraits. Born and raised in Strib at the Little Belt. After being trained as a painter with his father he sought in the early 1940s to Copenhagen. To prepare for the Academy of Fine Arts, he began at the Academy of Free and Commercial Art at Jarmers place by the painter Askov Jensen and cartoonist Tom Petersen (6 winters).Next, he applied for admission to the Academy in 1946 and was assumed to begin painting school with Professor Aksel Jørgensen in January 1947. Was taught one semester of Vilhelm Lundstrom and followed the teaching of Painting School and the School of Graphic forward to 1955. While such Maria Lüders Hansen (b. 1925) and Knud Bjerre (1921-2005).Study tours and exhibitions have – due to an excessive modesty – only shown a few times, including Strib Idrætsefterskole 1994 and Strib Sognegård “Paintings tells the story” 1996. Attended School trips include to Florence in 1950. stations’ statements Børge Jensen landscapes, still lifes, portraits and especially self-portraits show the artist’s constant search around reflex candles importance and his immersion in the study of mass displacements in space and scale. More photos could call to mind Edvard Weie and Karl Isaksons color.

Wish I knew what “reflex candles” actually meant, in Danish. It’s almost like finding a message in a bottle, tossed into the Baltic, washing up years later on the shore of Lake Ontario. There’s actually almost no information even in this quick bio, but this one passage stood out: “Due to excessive modesty, has only shown a few times . . .” What could be more anti-Warhol? What could be more encouraging and inspiring. To do such great work and rarely seek any attention for it . . . what a tonic for this era.

August 6th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Andy Warhol’s grave, now streaming 24/7, in Pittsburg

From the The Verge late last night. It may be a while before I take a look. Can’t wait though. It’s next on my list after I get through seven more hours of watching the Empire State Building do nothing and then there’s this film of a guy sleeping for five hours . . .

August 5th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Local art in Minneapolis for members of a cooperative. Courtesy NYTimes.

Works with lettuce. Works with art, as well. C.S.A. also means Community Supported Art.

August 5th, 2013 by dave dorsey

I found myself lingering quite a while last night at State of the Street-ish, an exhibit of street-inspired art at Rochester Contemporary Art Center, in partnership with the Memorial Art Gallery. It’s taken me far too long to get a look at Kurt Ketchum’s work, and I was even more impressed by it than I expected to be. Kurt’s paintings suggests graffiti in a tangential way, yet it’s street-ish because it conveys a sense that the objects he creates are almost ready-made segments of old city walls, covered with vestiges of posters, glue, weathered paint, and the scrawls of urban guerrillas armed with spray paint. The work requires time: you need to adjust to the visual language he’s developed, but the longer you look, the more the paintings draw you in and open up.

I found myself lingering quite a while last night at State of the Street-ish, an exhibit of street-inspired art at Rochester Contemporary Art Center, in partnership with the Memorial Art Gallery. It’s taken me far too long to get a look at Kurt Ketchum’s work, and I was even more impressed by it than I expected to be. Kurt’s paintings suggests graffiti in a tangential way, yet it’s street-ish because it conveys a sense that the objects he creates are almost ready-made segments of old city walls, covered with vestiges of posters, glue, weathered paint, and the scrawls of urban guerrillas armed with spray paint. The work requires time: you need to adjust to the visual language he’s developed, but the longer you look, the more the paintings draw you in and open up.

I’ve known Kurt for a long time. I was surprised that the show brought to mind what at first seemed an entirely random set of memories from a 90’s weekend I spent with him and a couple other friends, John Buck and Tom Curtin. The four of us golfed almost non-stop for two days in North Carolina on courses in and around Pinehurst. It was 36 holes a day. One of those marathons. The results were mixed from one round to another, but at one of the courses we played, you could rent a llama for a caddy. (I wish I had a llama story, but we declined them. Doh! Big hitter, the Lama. Long, into a ten-thousand foot crevasse . . . oh right, wrong Lama.) On the last day, we showed up in the morning mist, sleepy, dizzy, hungover and, frankly, intimidated by the first tee at a course called The Pit. It MORE

July 30th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Hot Summer Sky, Rick Harrington

A well-deserved win of the Harris Popular Vote Award at the 64th Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition. Way to go, Rick.

July 28th, 2013 by dave dorsey

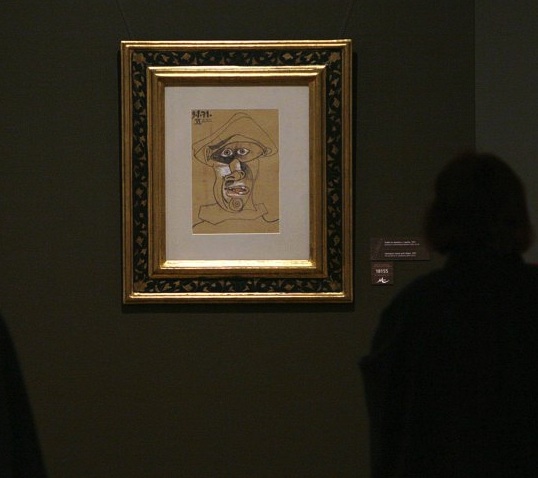

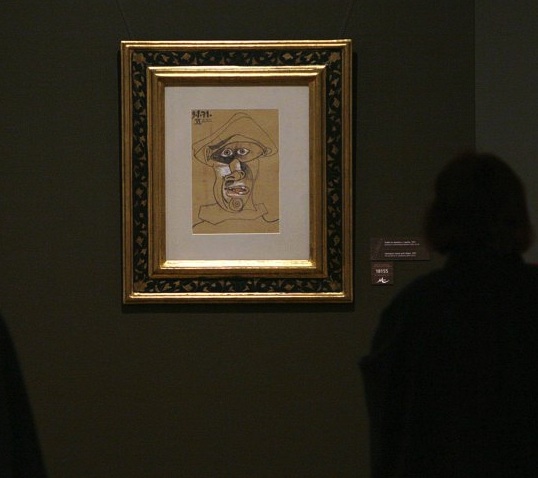

Harlequin Head, Picasso, destroyed by Romanian woman

There is some truth in this arrogant pronouncement that no one should mourn the burning of art, since most great art now is reproduced and ostensibly immortalized, in one way or another, on the Web. I’ve argued repeatedly here that seeing an actual, original work of art conveys far more than looking at any reproduction. Granted, there are a host of qualifications, especially with photography, conceptual art, and so on. Yet the difference between standing in front of a painting and looking at a photograph of it is roughly equivalent to the difference between meeting an actual person and examining a snapshot of her. What I like in this piece is the insistence on how the value of actually seeing an original painting or print remains an incredibly elite privilege. The total number of people who attend even the most popular blockbuster exhibitions represents a tiny percentage of the world’s population. Yet this doesn’t justify the cynical subtext here that the only people who are really hurt by the loss of an original work are an exclusive club of wealthy and educated collectors, academics and fellow artists. In a statistical sense, it’s true. But to say that all we need are good reproductions misses the fact that the physical presence of a painting, for example, conveys much of what the work offers someone who sees it. The heart of what’s conveyed by an actual painting remains inexpressible and can be captured neither through words nor through a reproduction. For me, it’s where the real power and meaning of visual art resides, inaccessible to analysis. It isn’t about ideas or concepts or an image that can be extracted from the medium used to render it, like the solution to a puzzle. A painting is as much about the humble, colored mud used to create it as it is about what that medium allows you to imagine. And that’s partly why individual, unique works of art sell for such inflated prices. No one would disagree with the assertion that burning paintings is not an act equivalent to genocide. It would be ridiculous to suggest it, but the loss of original works of art is a loss to mourn, at least a little, and what should be mourned most of all is the way in which, over the past hundred years, part of the actual reality, the essence and being, of painting seems to have been obscured, if not forgotten. Which allows people to write explanations for why you shouldn’t care when a Picasso or Van Gogh gets burned.

July 26th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Eric Fischl, from L.A. Times

From the L.A. Times, an interview with Eric Fischl, on the occasion of his book, Bad Boy: My Life On and Off the Canvas:

You write about how the art world became all about the art market after Wall Street soared in the ’80s, and that the art market, which involved conflicts of interest, went on to determine intrinsic value. Can you talk about that?

It was almost like a perfect storm. There was a tremendous amount of money being made by people who were very young, were not broadly educated but were more mono-focused educated. They didn’t have a broad sense of history, of culture. Then all of a sudden there’s this infusion of money into the art world, where they’re looking for things that are not deeply understood but are entertaining, and the lifestyle of it is entertaining. They’re hedging their bets, so they’re buying lots of different young artists. And it’s getting younger and younger. In the ’90s, collectors started to buy work directly out of studios in graduate schools by artists who hadn’t even become professional artists, let alone mature.

And the impact that has on artists is enormous, because if you start selling work as a student, it’s very hard to change, very hard to let go and progress and find your own true voice. So you see a lot of younger artists who’ve been selling work since they got out of school but have yet to do their second show, so to speak. They started speaking, not in art terms, but in business terms. People wanted to know how to be branded, they wanted to know about price points.

Something else that’s continued since then is the growing gap between rich and poor, with the rich getting richer and the middle class, which was your subject matter early in your career, diminishing. How is this influencing art?

It’s an awkward situation for people who make objects because they’re aware that they put them into a system that essentially only the rich see or buy. Museums have gotten to the point where they’re so expensive to go to, you’re also limiting access to people who don’t have to buy the art, so they can’t even get in to see it. And then there are a lot of younger artists who are rejecting the gallery system pretty much altogether. They’re trying to engage communities directly and are doing nonobjective type of work, so they can’t be commodified as easily. It remains to be seen whether that’s going to be something that becomes a dominant form for art. My primary thing is to make a painting, not necessarily to make a painting to sell for gazillions of dollars, but just to make a painting. But somehow the market has made it such that nobody talks about talent anymore. It’s almost politically incorrect to talk about an artist having talent, because then it’s exclusive.

Whereas the price tag isn’t?

It’s weird. The price tag has replaced it, and it’s certainly not a critical dialogue. It’s just something that’s a symbolic thing where it must mean the person who sells for the most money is the best artist.

July 25th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Double Portrait, Lucien Freud

In the current Harper’s, this could be my new favorite by Lucien Freud.

July 21st, 2013 by dave dorsey

Samothracae, Jack Elliott

It’s impossible to do justice in a single blog post to a show as excellent as the 64th Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition at Memorial Art Gallery. Its effect is cumulative, as you wander past a hundred individual works. I learned recently that the heart rate of singers in a choir quickly synchronizes—so that every individual singer’s heart somehow times its pulse to the beat of every other heart in the choir. You get the sense of 81 unique hearts working in unison here as well, even though the artists live hundreds of miles apart, across the state of New York, pursuing a quiet, personal excellence. Each voice here is individual, operating in accord with its own unique set of stylistic principles, yet you feel the same passionate allegiance to private imperatives from one work to the next. You sense in this show a universal determination, across all the work, to focus on the slightest choices—how to render a line in a woodcut, how to stick to a certain kind of mark on canvas, how to check one’s ambitions into the confines of an unspectacular scale—as hard-won personal standards that result in mastery for that individual and no other in quite the same way. Jack Elliott’s Samothracea, the most powerful piece in the show, unapologetically reaches back many centuries for inspiration (it magically evokes its sculptural ancestor by pairing two enormous segments of willow trunks into a human torso that appears to be both in motion and standing still), while Donna Meadows Manier’s monoprint Luxury could be seen as sly up-to-the-minute commentary on our currently lopsided economy where a commodity can become an symbol of exclusive taste. In terms of diversity of style, purpose, and medium, you find yourself in a different world every time you take another step through the exhibition. But in each individual case, the craftsmanship is so uniformly subtle and understated, what’s happening in each work might slip right past you if you don’t dwell for a bit and give yourself time to see it. The spectacular nature of so much contemporary art has been shrugged off here in favor of values and dedication that don’t scream for attention but seductively invite it.

Since 1938, the Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition has served as a platform MORE

July 18th, 2013 by dave dorsey

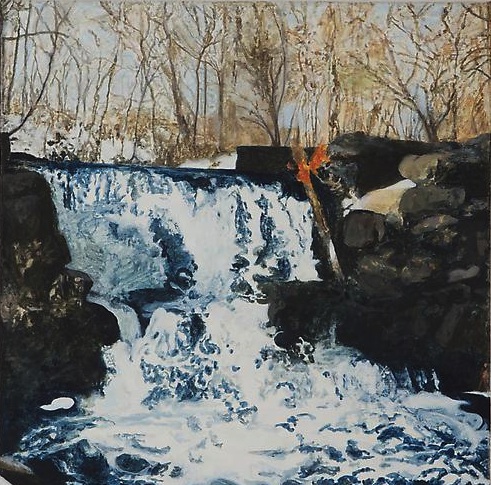

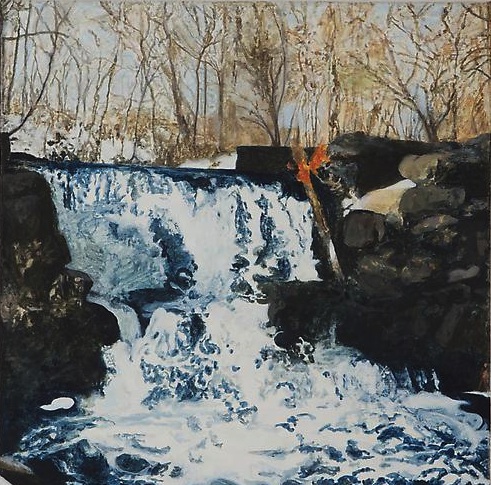

My work at the Memorial Art Gallery

I have to admit it’s cool to see my work hanging on a wall in our local museum only a few steps away from the spot where I stood when I was 18 and saw my first Rembrandt, Portrait of a Young Man. As part of the permanent collection, Rembrandt’s painting will be inhabiting the Memorial Art Gallery far longer than my work will. I’m on view for a couple months. (When you stand in a museum whose website tagline is “Fifty Centuries of World Art” you become hyper-aware of how little time you spend doing anything.) The 64th Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition, which accepted three of my paintings, will last until Sept. 9. Yet, as evanescent as my tenancy is there, my second participation in this exhibition (I sold my entry in the same exhibition four years ago) has given me a sense that the decades I’ve spent practicing, experimenting, learning, and building up one side of my back muscles from holding a brush aloft (I kid you not) have resulted in work that offers something of value to other people. I’ve had confirmation of this over the past five years, as I’ve begun to exhibit around the country and even in London, and I’ve sold a fair number of paintings, but this show always feels like the highest honor to me. Maybe because it happens here in what has become my home town, and maybe because the quality of the work, especially this year, and the quality of this museum, seems equal to anything I see anywhere I’ve looked at contemporary art. So the honor of being in this biennial show gives me a sense of achievement, but it also gives me a keen awareness of the humbling ironies implicit in being a visual artist now. Or almost any sort of dedicated, disciplined artist.

Artists in any field–poet, painter, musician, novelist, short story writer, actor, photographer, comic–do something that can represent a genuinely rare achievement (given the population of the world) and yet still be almost totally unknown and obscure (given the population of the world). Take it up to the highest notch, and this still holds true. You can even make a lot of money at what you do, be highly recognized in a given field, get profiles in glossy magazines and still labor in almost total obscurity when it comes to the human race as a whole. Part of the drive to be creative is to fashion something that could potentially have meaning or be a part of almost anyone’s life, in any time. Universal and timeless are a tired pair of adjectives that describe great art. Postmodernism aside, that’s the unspoken hope and dream of every artist: to make something that deserves those adjectives. And yet even the most celebrated and lucrative work, the art that reaches the most people and has the greatest chance of being seen years into the future, has little impact on most people. Jeff Koons is probably one of the most publicized and controversial artists now living and yet almost no one would recognize his face on the street. Nor would most people be familiar with his name or his work. I think those who devote their lives to art tend to forget how much it takes place in a comparatively tiny social bubble, at various levels–local, regional, national, even international. The global audience even for the MORE

July 10th, 2013 by dave dorsey

A student at Protsohan in New Delhi

A great, through brief, story on how one woman, Sonal Kapoor, is teaching art, design and photography to help poor girls in New Delhi escape lives of despair. The program also has a Facebook page. I loved their mission statement there: “Encouraging Skills Development & Creative Education through DESIGN THINKING at the bottomest of pyramid.”

June 30th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Ithan Creek, Peter Allen Hoffman

I found the current show at Freight + Volume both disappointing and encouraging, which, if you think about it, ought to be a hard thing to pull off. It was a bit of a letdown in a way that I’ve experienced several times over the past couple years. It goes like this. Paintings that intrigue me when I see them reproduced on a website look much less vibrant and resonant in person. They aren’t as alive as I expect them to be. A surface richness I think I see in reproductions isn’t there when you stand before the actual work. (I remember reading an account of this same experience from someone who had gone to a show of Natalie Frank’s paintings.) It happened, for me, at Walton Ford’s most recent show at Kasmin. I still admire his scenes as much as ever, for many reasons, but I’d expected to revel more in his paint handling. Standing a couple feet away from the images, I wasn’t as charmed by them. Do I quibble? Probably. Would it matter to anyone other than a painter? Probably not. Yet, in some way that’s hard to explain, I felt a little conned at the surface level of the work. His interest didn’t seem to be in the paint itself, but in simply creating the illusion he wanted, as expeditiously as possible. Those same words could be applied as high praise for the work of Sargent or Hals or Vermeer or Fragonard any number of other painters—mastery often means getting the most powerful results out of the least effort. But up close a Vermeer remains as much a marvel of execution as it is from five feet away. Not so much with Ford. His work left me feeling as if the act of painting was something he was impatient to get past. At the recent Durer exhibition in Washington, for example, I never felt that way: MORE

June 28th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Peonies from Chris Lyons. Harrington wondered why not do it as an actual serigraph, in whatever way Warhol did it. I wondered why not do it as big as Warhol did a serigraph. The difference would be, no irony. In any case, we want more, Speedy. Only large. Big Warhol serigraph, only larger. Just thinking aloud. I liked the white background better in the email you sent.

June 27th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Parquet Courts delivered. Sadly, the Post Office didn’t.

Represent is about the painting life. It says so up there on the banner. As of today, it’s also about shipping, which is a crucial part of the painting life (if you care to show your work to other people in a public way.) Mostly, over the past two years, I’ve been writing about the painting part, and not much about the life. So I’m going to correct that with a lesson on how not to attempt something absolutely essential to this pursuit: frugality. It’s always a good idea, in any field, to spend as little as possible, but especially as an artist. With that in mind, it would seem a no-brainer that I shouldn’t vacation in, say, Palm Springs. Or play golf. (Or visit New York City for that matter. You know how much parking costs in Manhattan? I don’t have the heart to tell you.) But if both your kids live and work in L.A., and you get to see them once a year when they come home for Christmas, going to L.A. for a week in the summer is the best option. This is because it’s exceedingly hot in the desert in July, when rounds of golf and rental homes are as inexpensive as they ever get there. During July, it would cost more to golf at many public courses here in Rochester.

So we save up my wife’s earnings from teaching second grade, and we spend a week with our kids in Palm Springs (much less expensive, actually, than staying virtually anywhere closer to L.A. itself), during one of the hottest weeks of the year. A round of 18 holes at Indian Canyons Golf, where my son Matthew and my son-in-law, John Bridge, and I will be playing every morning during our annual week in Palm Springs, costs $45 for eighteen holes, per player, unless you buy a summer discount card for a one-time fee of $65, which lowers the greens fees to $30 per person, every day, for the six days we play. A couple hundred dollars of savings! Beautiful. I’m a painter so, as you know, I can find the beauty in many things, including a vacation where the daily high will be 115.

Which brings me to the subject of the U.S. Postal Service. I know, that’s a pretty bumpy transition, but it will make sense if you stay with me. MORE