Archive Page 27

March 22nd, 2015 by dave dorsey

From Hyperallergic, (thank you, guys, for staying alert to the most remarkable thing going on in the city right now, in terms of art). Such an incredible opportunity, which I’m going to attend tomorrow. Apparently this museum is on its last legs, according to the Times. No surprise, there. Nice way to go out, by making history. I really want to see Donatello’s visualization of Abraham and Isaac, a father ready and willing to kill his son, which I expect will be a representation of all war, from pagan times to the present, a long history of human sacrifice and violence–as well as its specific meaning in the Old Testament. Hyperallergic:

It’s an improbable exhibition, with 23 early Renaissance pieces that have rarely (if ever) left Italy, let alone crossed the Atlantic to arrive at this small Upper West Side museum. After their return to Florence’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, it’s likely most of these pieces will never travel again because of their fragility and size. The exceptional nature of the exhibition is reason enough to visit, but the unexpected humanity of Donatello’s sculptures up close makes it essential.

And some other qualities, as well, make it once in a lifetime, for those of us who can’t fly to Italy. When they say pieces, I think what they actually are talking about are large, heavy, and apparently fragile sculptures craved from stone. But it sounds as if they are too fragile for even a second journey like this. (Is all the world as temporary as flesh? Yes. But does Donatello have to remind me with stone? Yes.) Which is to say, see it now. It won’t happen again.

March 20th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Field Flowers, Fruit, and Dishes, Fairfield Porter, 1974, oil on masonite, Alexandre Gallery

Painting is an art that favors the old, who’ve been at it for decades. From the last year of his life, give or take a few months, when it seemed he could do no wrong and everything looked both effortless and exactly right. I found this image at the Alexandre Gallery‘s website yesterday but cannot find it now . . ..

March 18th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Christmas in July, oil on panel, 6″ x 6″

A new Matthew Cornell show is opening at Arcadia just in time for me to visit this weekend, or early next week, while I’m in the city. His astonishing, small paintings look better and better. He somehow captures the light of less-illuminated things during a photographer’s beloved Golden Hour, just as or after the sun sets or rises. He somehow manages to evoke details and variations of color in the shadows, illuminated faintly by the sky itself, while creating a focal point with a small area of orange or yellow artificial light, usually from the window of a house. How he gets the amazing level of verisimilitude at the tiny scale of these paintings is a mystery, unless, as it seems Durer must have done, he uses brushes with a single hair. He can have as many as three light sources–the sky, the interior light glowing from windows and a streetlight or the sun itself shining somewhere beyond the frame of his picture, throwing another angle of illumination onto a house or strip of grass. What distinguishes his work, though, is the intense, complex feeling the images evoke–stillness, peace, satisfaction, beauty, yet also loneliness and isolation. In this show, as described in an excellent video he has produced, he returns to houses where he has lived and paints them, using photographs he takes at the site. He pushes the color just slightly so that a pair of yellow no-passing lines in a road look orange and his greens seem slightly more lush than they would in any photograph I’d be able to take. A neutral shadow becomes faintly purple next to the amber incandescence of a porch bulb. The ultimate effect is something both convincingly real and yet magical: Christmas in July. Actually, for me, it’s like Christmas morning every time I look at one of his paintings for the first time.

March 16th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Klettur, John Zurier, oil on linen

John Zurier’s work looks strenuously minimal, and therefore offers little to grab onto. Still, there’s a feeling of monastic restraint and genuine feeling in his paintings, which often seem to be modest in scale, a feature commensurate with how self-effacing they are in other respects. All of those virtues are concentrated into one or two colors. Is that enough? I can’t tell from here. He appears to give me less to look at than I ordinarily like, but that could be a way to rewind all the current media noise. And maybe the lack is in myself, rather than in the paintings. It’s hard to say without seeing them, which I may try to remedy at Peter Blum on my venture into NYC next week. I think I would have passed on this, but for his artist statement, a requirement that I usually hate, but this one I love:

“I remember the first painting problem that really engaged me. I tried to paint the sky seen between two buildings so that the whole of my painting would be nothing but an empty blue space. I wanted the painting to be filled with a pale empty sky. I thought it would be very easy to do, but found it nearly impossible. The painting was a failure and I had to put it off for a long time.

In a way, my concerns now are not much different in that I want the maximum sense of color, light, and space with the most simple and direct means. I think the Japanese painter Ike No Taiga (1723–1776) was right: the most difficult thing to achieve in painting is creating a space where absolutely nothing has been painted.”

January 2008

March 13th, 2015 by dave dorsey

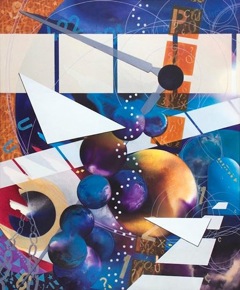

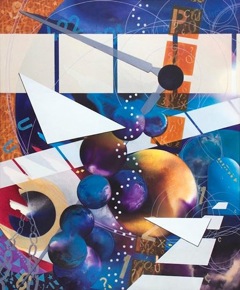

Bill Santelli, The Systemic Path, acrylic on canvas

This painting by my friend and fellow Oxford Gallery artist, Bill Santelli, is on view in”Cosmos–Imagining the Universe,” an exhibition sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution, in the Annmarie Sculpture Garden and Arts Center in Dowell, Maryland. Bill works in several different abstract modes, including prismacolor drawings I love. The Systemic Path is closer to the abstract work he does now in acrylic, but it’s from an earlier period. The exhibit runs from: February 13 – July 26, 2015. Bill and Tom Insalaco and I met for a couple hours last week to talk about what we’ve all been up to and, as a follow up, Bill suggested we have a small group show of work we’ve been doing, off and on, without ever submitting it for exhibition: in other words a show to offer a glimpse our semi-secret lives as painters. I like the idea, but it’s going to be up to Bill to take the initiative. He sounds eager to do it. We also think Tom deserves a big retrospective: he’s a great painter who has long deserved serious recognition, in addition to his extensive list of awards.

March 11th, 2015 by dave dorsey

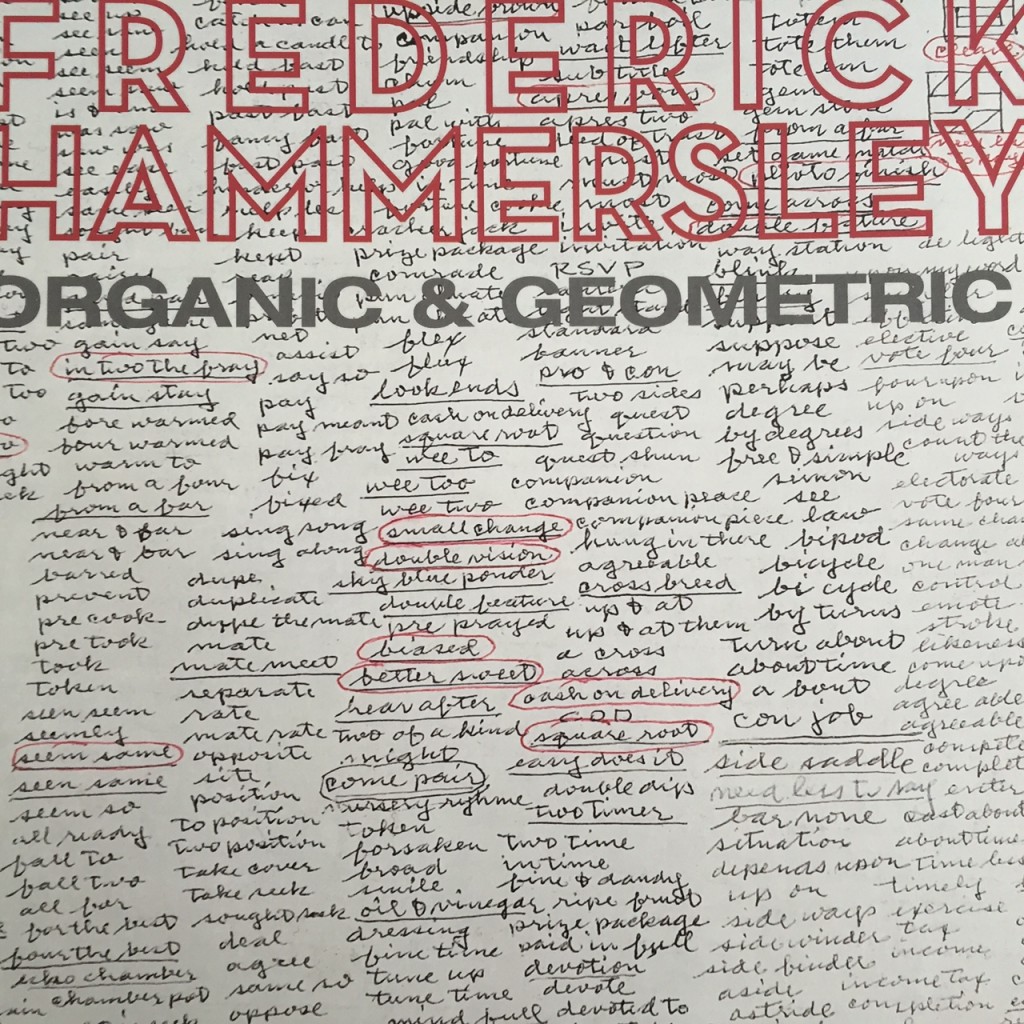

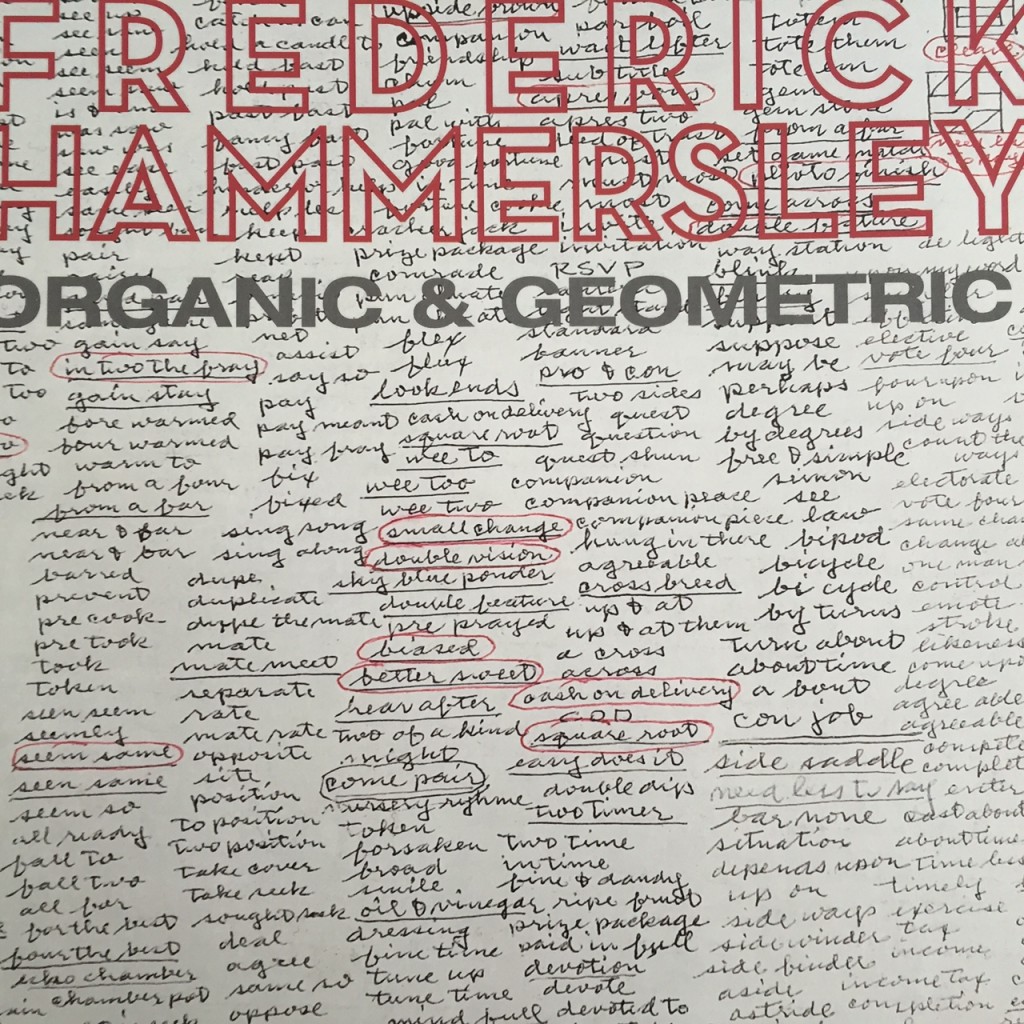

Dupe. Duplicate. Dupe the mate. Mate. Mate meet. Separate. Rate. Mate rate.

That’s a stream-of-consciousness improvisation, a free association of possible painting titles from Frederick Hammersley. When you string them out into a line that way, it sounds like a mordant poem about a bad marriage descending into sordid one-night stands with strangers. Yet those words, in that order, are from the lists of brainstormed titles (above) from Hammersley’s notebooks. His pages are reprinted on the covers, and inside the covers, of a slim, beautifully printed catalog published for a show I saw at Ameringer, McEnery, Yohe three years ago. I hate titles for paintings–shouldn’t paintings just be numbered or dated?–but in Hammersley’s case the titles can supposedly enhance your ability to see what’s happening in the work, as the catalog’s essay by David Reed examines in an interesting way. Yet the stacks of words all seem slightly parasitical to me, as if the unused side of the artist’s brain is getting even for all the fun his alternate number is having. Hammersley’s hues are the most unadulterated and intensely saturated colors of any oil painting I’ve ever seen. Noland and Stella invented sophisticated color harmonies you hadn’t seen before, but Hammersley seems to offer his unambiguously radiant colors in ultra-simple compositions, contained in mostly uniform squarish spaces, as if to say, look what I found today! Have you ever seen a yellow like that! Each of his colors seems an end in itself, pure play, regardless of whatever else is placed around it. Each color he puts down plays well with others and seems the king of infinite space, all at once. And then there are those lists of titles that either make you laugh or wonder what he meant, such as In Two the Fray, Altered Ego, Savoir Pair, but either way, once you see the title, the thinking takes over and the looking falls in line behind it. Doh.

March 9th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Green Sky Landscape, Charles Webster Hawthorne

As a follow-up to my previous post on my visit to the shows about perceptual painting in Maryland, I read a small book put together by the students of the man who inspired those two exhibits. When Hawthorne talks about how reasoning should not be part of painting, he means something specific: when you paint a person or a house, don’t paint as if you were a surgeon or an architect, simply see the spot of color it forms in your field of vision and paint that, not work form any prior knowledge about the “thing itself.” In other words, be a phenomenologist. But he also suggests that larger reasoning, theories or ideologies or conscious points of view about life are also alien to the sort of painting he advocated. Intentional narrative, message-imparting, intellectual content only turn painting into a package for some precious thought inside it. It becomes rarefied illustration of the thought comes first, the knowledge, and the painting serves it: the painting should give rise to thoughts, if there are any to be had, but mostly it should convey what it is through seeing, not thinking. That wasn’t how painting worked for him, and was probably at the heart of what drove the Impressionists, who were Hawthorne’s predecessors, to rebel against academic painting that served to illustrate classic myth, Biblical stories, and historical narratives. Painting had become a form of illustration. For Hawthorne, there should be no thought involved in the motive for a painting other than the logic of how it is shaped and how the colors are chosen, for no other purpose but to see the beauty in, essentially, everything, including the train station, as he like to put it. Not simply for the pleasure of visual experience. Seeing, for him, I think, was about far more than the visual sensations you get when you aim your eyes at the horizon or a bottle or a face. It’s about embracing an entire world by glancing at one small part of it, and if the painting is good enough, subconsciously, a certain wisdom about that world comes along with the perception of beauty. Abstract reasoning, beyond the logic of how to construct an image, only gets in the way of that.

From Hawthorne on Painting, Charles Webster Hawthorne’s advice to his students:

It is not the sentimental viewpoint but the earnest seeking to see beauty–in the relation of one tone against nother–which expresses truth–the right attitude. If you’re a thoughtful humble student of nature, you’ll have something to say–you don’t have to tell a story. You can’t add a thing by thinking–what you are will come out.

You cannot bring reason to bear on painting–the eye looks up and gets an impression and that is what you want to register. Painters don’t reason, they do. The moment they reason they are lost–subconscious thought counts. MORE

March 7th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Still Life, David P. Jewett, oil on linen on board

This stove is painted with a soul–there is as much beauty and religion in this painting of this black iron stove as in any of your so-called religious paintings. That is sacred–you have put your heart in it. One of the greatest things in the world is to train yourself to see the beauty in the commonplace . . . a freight car or a wash line of clothes . . . — Charles Webster Hawthorne

At two recent exhibits in Maryland, I saw paintings far quieter and more subtle, and therefore a lot more emotionally compelling, than the superficially clever, high-priced spectacle that routinely flows through the art market. It was a genuine relief how these shows created the sense of an uncovered tradition in the practice of visual art reaching back into the 19th century (and maybe further), a tradition where less is more, where the small trumps the huge, and silence is more inviting than showmanship. At first the paintings can look familiar and comfortable, as if they were witnesses to the past relocated into the present and given new names, but when you apply some sustained viewing to them—and listen to someone like Matt Klos, the curator for A Lineage of American Perceptual Painters, which just closed at The Mitchell Gallery—these painters can be surprising, unpredictable, and revelatory. Even the oldest, historical work Matt assembled for the show in Annapolis felt alive, fresh, and even offbeat, offering qualities I hadn’t noticed before even in a few of the paintings I’d seen in the past.

I met Matt a number of years ago when I began exhibiting at Oxford Gallery here in Rochester, where Matt grew up. I liked his work immediately and began to follow what he was doing over the past five or six years. I wanted to ask him more about how much effort was involved in putting the show at Mitchell together, but we didn’t have enough time to do that in the three hours we spent together, too busy talking about the work and exchanging thoughts about painting in general. The MORE

March 5th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Bridal Accessories, detail, Richard Estes

I really want to see this one. From the article on a Richard Estes exhibition with, for the first time, his photographic sources: “What this exhibition makes clear is how unrealistic his Photorealism is from the standpoint of photography.”

March 3rd, 2015 by dave dorsey

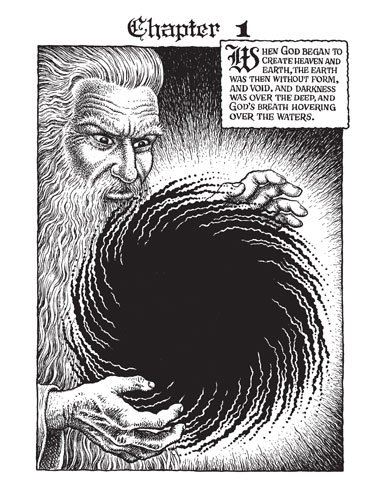

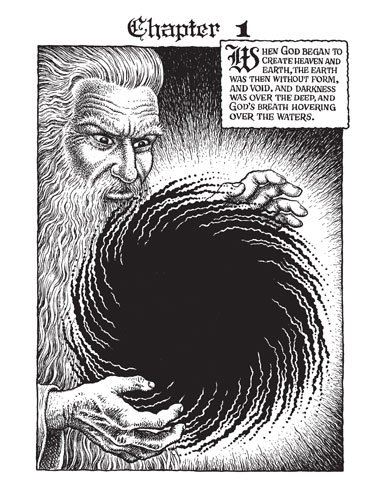

R. Crumb keeps on truckin’. He recently put in four years as a hired illustrator. And it was very good, apparently. I loved Classics Illustrated as a kid. He doesn’t exactly sound grateful, though. Blake would have loved the gig. From Paris Review:

R. Crumb keeps on truckin’. He recently put in four years as a hired illustrator. And it was very good, apparently. I loved Classics Illustrated as a kid. He doesn’t exactly sound grateful, though. Blake would have loved the gig. From Paris Review:

INTERVIEWER

Let’s begin with Genesis. Where did this book come from?

R. CRUMB

Well, the truth is kind of dumb, actually. I did it for the money and I quickly began to regret it. It was an enormous amount of work—four years of work and barely worth it. I was too compulsive about the detail. With comics, you’ve got to develop some kind of shorthand. You can’t make every drawing look like a detailed etching. The average reader actually doesn’t want all that detail, it interferes with the flow of the reading process. But I just can’t help myself—obsessive-compulsive disorder.

February 28th, 2015 by dave dorsey

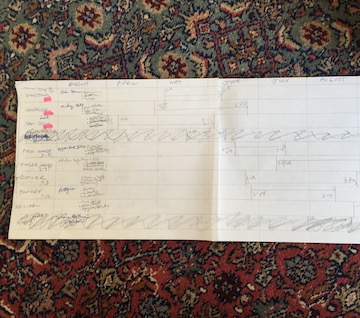

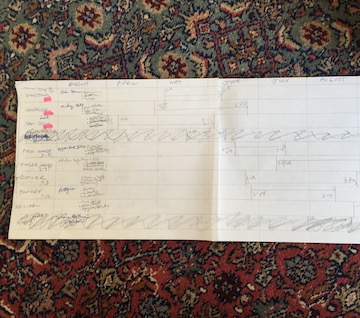

This is how I plan my year in terms of exhibitions. A pencil. A straightedge. Some lines to see how shows do or don’t overlap, so I won’t have to send the same painting to two places at once. Almost everything I would want to get into is listed. The ones at the top with the pink dot I’ve already entered. There are so few juried exhibitions anywhere that seem worth entering–surprising because it seems like an easy way to draw in revenue, with the accumulated fees. Maybe eight possibilities this year, in addition to my two-artist show at Oxford Gallery. Manifest might have something down the road that’s worth a try. I skipped several I got into last year, just because I thought it was unlikely that I could get into them again. I chart out the dates between delivery of the work and end of the show, so that I can see at a glance which ones leave enough wiggle room for me to get a painting back in order to resend to another show. Most of them overlap. The “season” is mostly in the warmer months, even though a lot of shows are in the South. Two of these are other member-run galleries like Viridian Artists (which I don’t have the money to join again), which is fine because they have good jurors, though I’m not looking to be a gallery member. Slim pickings, but a whole morning’s work to chart this out. I’d already researched and found these shows using directories of juried exhibitions on line, weeks ago, for the most part, though I found the last one only a couple days ago. Simple, humble stuff. Yet the CV I build from it matters. If I start approaching commercial galleries in New York, the long list of shows I’ve been in, and the places that have let me exhibit, will demonstrate that the work is worth considering. The lack of solo shows is a minus, but I haven’t had the body of work to do one really. I’ve sold a lot of what could expand a portfolio. I might start later this year proposing a solo show at Manifest with whatever I’ve got on hand plus the work I do between now and the fall. Then start looking for other places; but I want to knock on some doors in New York City later in the year, maybe late summer/early fall. Given the way the market works, few galleries are probably scouting for new painters, but I won’t know unless I try. I’d like to produce six smaller still lifes, like the onion I recently finished, as the core of the portfolio and then add half a dozen more from what I’ve done so far. A few very quick paintings too–I want that to become a habit.

This is how I plan my year in terms of exhibitions. A pencil. A straightedge. Some lines to see how shows do or don’t overlap, so I won’t have to send the same painting to two places at once. Almost everything I would want to get into is listed. The ones at the top with the pink dot I’ve already entered. There are so few juried exhibitions anywhere that seem worth entering–surprising because it seems like an easy way to draw in revenue, with the accumulated fees. Maybe eight possibilities this year, in addition to my two-artist show at Oxford Gallery. Manifest might have something down the road that’s worth a try. I skipped several I got into last year, just because I thought it was unlikely that I could get into them again. I chart out the dates between delivery of the work and end of the show, so that I can see at a glance which ones leave enough wiggle room for me to get a painting back in order to resend to another show. Most of them overlap. The “season” is mostly in the warmer months, even though a lot of shows are in the South. Two of these are other member-run galleries like Viridian Artists (which I don’t have the money to join again), which is fine because they have good jurors, though I’m not looking to be a gallery member. Slim pickings, but a whole morning’s work to chart this out. I’d already researched and found these shows using directories of juried exhibitions on line, weeks ago, for the most part, though I found the last one only a couple days ago. Simple, humble stuff. Yet the CV I build from it matters. If I start approaching commercial galleries in New York, the long list of shows I’ve been in, and the places that have let me exhibit, will demonstrate that the work is worth considering. The lack of solo shows is a minus, but I haven’t had the body of work to do one really. I’ve sold a lot of what could expand a portfolio. I might start later this year proposing a solo show at Manifest with whatever I’ve got on hand plus the work I do between now and the fall. Then start looking for other places; but I want to knock on some doors in New York City later in the year, maybe late summer/early fall. Given the way the market works, few galleries are probably scouting for new painters, but I won’t know unless I try. I’d like to produce six smaller still lifes, like the onion I recently finished, as the core of the portfolio and then add half a dozen more from what I’ve done so far. A few very quick paintings too–I want that to become a habit.

The tricky part in all this entry scheduling is the possibility of a sale early on, which I’d have to make contingent on being able to show the work in a later show. I could always show in the earlier exhibitions without putting a price on the work.

February 24th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Still Life with Pocket Door

If someone were to ask me right now what my painting is about, I might offer something that would probably occur to me if I were someone else appraising the work I’ve done over the past couple years. I might say Dorsey is continuing to work in several different modes: adding to the series of large jars he has exhibited in the past, doing a few suburban landscapes, and exploring smaller alla prima paintings executed very quickly, almost like Japanese sumi-e. In all of this work, he’s drawn to the ordinary and everyday. Mostly, though, he has continued his central pursuit of fairly traditional still life. His love for this genre seems to come from a variety of influences. Yet the effect of these paintings when seen together, aside from whatever virtues still life has always had, is to make one feel as if the artist is wistful, even desperate, for a world that’s fast disappearing. There’s something about these paintings that reminds one of the rag waved in the air by the uppermost member of that pile of survivors in Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa, the one trying to catch the eye of a savior on the tall ship just emerging over the horizon before time runs out on the life raft. In a time when the middle class seems to be rapidly disappearing, taking with it the promise of opportunity for most people in our society, Dorsey seems to be drawn again and again to the subject of domestic serenity as embodied in a little heirloom sugar bowl or a couple flowers from a backyard garden. Intentionally small potatoes—though, strictly speaking, he hasn’t painted any potatoes yet. Domestic happiness was the daemon of both Chardin and Vermeer, two painters who have had a powerful sway over his work so far. It isn’t a small thing, though, to have reminders of what it meant in America to have a flourishing middle class, a thriving bourgeoisie so despised by intellectuals, the economic topsoil of a robust free society, something fast disappearing in the world right now.

This might be what someone would say about the paintings in this show, though it’s merely hindsight and speculation on my part. None of this even crossed my mind as I’ve done this work, MORE

February 22nd, 2015 by dave dorsey

For an bit of interesting commentary on the power of contemporary media, try the first episode of Black Mirror. It’s also a sidelong statement about . . . well, watch. The series as a whole is well done.

February 22nd, 2015 by dave dorsey

Dining Room into Living Room, Mark Karnes, 2009-2012, acrylic on Masonite

In fortuitous lulls during the Siberian Express of snow and frigid temperatures here in the Northeast during the past week, I drove six hours to Maryland to see two fantastic exhibits, both devoted to “perceptual painting.” One, organized by Matt Klos, tracks the largely unrecognized history of this movement, showing how perceptual painting enables representational art to evoke a liminal, dreamlike intimation of a world around and within the surface of things. That may be a pretentious-sounding way to say that perceptual painters enable you to see what they saw, mostly through direct observation, but they also convey a loving, sustained hunger to evoke something much larger, the poetry of the everyday. I’m getting ahead of myself, though. I want to write a long post about both shows, or maybe several posts, when I’ve tackled some other things on my plate, and this is simply a quick reminder for anybody within a few hours of Annapolis to invest an afternoon on these shows before they come down. It’s some of the most compelling painting being done right now, and it’s also an interesting attempt to further define what “perceptual painting” is, in the wake of earlier shows, such as the one recently at Manifest and a year ago at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. It kills me not to be able to attend the exhibition events today, but I pass this note along from Matt Klos for anyone able to attend:

My curator’s talk for “A Lineage of American Perceptual Painting” has been moved to Wednesday, February 25th at 5:30pm located at St. John’s College in the Drawing Room adjacent to the Mitchell Gallery. There will be ample time to walk through the gallery before and after the talk. St. John’s College, Mitchell Gallery, 60 College Ave, Annapolis, MD 21401

A panel discussion for the exhibition will be held this Sunday February 22nd at 3:00pm also located at St. John’s College. Follow signage when you arrive to the gallery… we will either meet in the auditorium or the drawing room depending on turnout. Although not required please call the gallery to rsvp for both events,

410-626-2556.

St. John’s College, Mitchell Gallery, 60 College Ave, Annapolis, MD 21401

“Lineage” Artists and Panel Discussion participants will include:

James Fitzsimmons

Elizabeth Geiger

Philip Geiger

Mark Karnes

Scott Noel

Charles Ritchie

Aaron Lubrick and Matt Klos will moderate. Several questions will be asked of the panel including this one, The painter Jake Berthot in a letter to Ryan Smith once wrote, “The mind lies and is capable of making a justification for anything. The eye and the hand are incapable of lying. Look with your heart and it will tell you through your eye what your hand needs to do.” Can you talk to us about what you think Mr. Berthot may have meant? What does that statement mean to you? I hope you’ll come join the conversation.

Special guests Erin Raedeke, David Campbell, and John Lee will also attend the Panel Discussion. These artists currently have work on view at Anne Arundel Community College in the Cade Gallery in an exhibition “Subject & Subjectivity” curated by Matthew Ballou. On the day of the Panel Discussion (Sunday, Feb. 22nd) artists will be on hand in the Cade Gallery to discuss the exhibition starting at 1pm. John A. Cade Center for Fine Arts, Cade Gallery, 101 College Pkwy, Arnold, MD 21012

February 20th, 2015 by dave dorsey

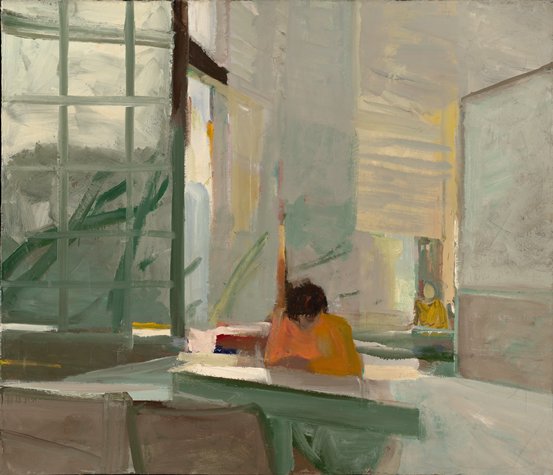

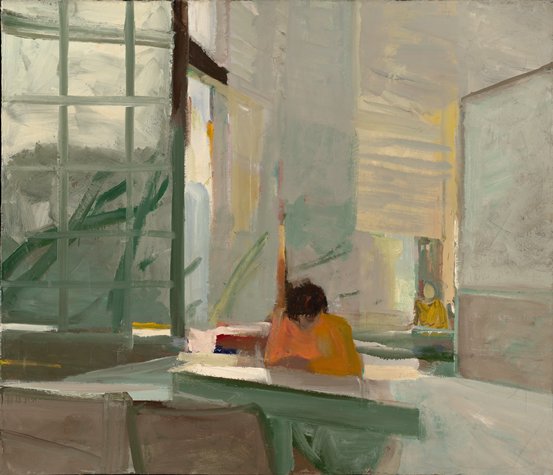

Orange Sweater, Elmer Bishoff

February 16th, 2015 by dave dorsey

My lifelong, simmering interest in Martin Heidegger, plus my recent quick rereading of early Nietzsche, has a couple friends wondering if I’ve become a dreaded existentialist, whatever that is. (No doubt this would mean someone who understands what “existential threat” means.) The answer would be “no.” My faith, humble and simple and nonsectarian as it is, remains unshaken—it’s a way of life, not a set of propositions about the world. But Heidegger keeps appearing in my path, even when I’m not seeking out books or essays about him. For example, while painting this week, I caught up with some of the latest episodes of In Our Time, a great, brisk discussion from the BBC about almost any subject as long as it’s dense with information: history, music, religion, art, and philosophy. I clicked on the “Phenomenology” episode and listened to a discussion that repeatedly reminded me of why I started painting years ago, as a way of seeking “meaning.”

Melvyn Bragg had three guests: Simon Glendinning, from the European Institute at the London School of Economics, Joanna Hodge, from Manchester Metropolitan University, and Stephen Mulhall, from the University of Oxford. The discussion turned out to be a sort of back door into an examination of what has generally been called “existentialism” though none of the panelists ever once used the word, instead referring to Heidegger and Sartre as phenomenologists because their work descended from Edmund Husserl’s. This off-the-cuff dissection of phenomenology was articulate and effective—and quick—so I’m going to reproduce some of it here, partly because by the end of the podcast I was struck by how much painting is, or should be, a phenomenological exploration.

Here are portions of the conversation, paraphrased and condensed in places, starting with an overview whose bearing on representational painting should be glaringly obvious:

Stephen Mulhall:

Phenomenologists are fascinated and struck by the fact that we grasp and comprehend all of the various entities that the world throws at us in the course MORE

February 14th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I’m an avid admirer of Suzie MacMurray’s work, after stumbling onto her show at Danese/Corey in 2013 and spending quite a bit of time there absorbing it. I got an email from her about a new installation, Cloud, to commemorate the loss of British soldiers in the First World War. Wish I could get across the pond to see it, but I’ll be checking for glimpses via the Internet. Sounds intriguing, and substantial, and no doubt brilliantly done.

February 12th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Memorial Art Gallery at Night, Jim Mott, oil on board

I had a desultory conversation with Jim Mott recently, touching on why we paint, so I’m just going to leap into it in media res:

Jim: In a better world the agenda for painting since the Sixties might have been to integrate the abstract and the real.

Dave: Everybody tries to some degree. I think that’s really what painting is, even the most abstract is representational and vice versa.

J: But to have the dialog between them . . .

D: Right. What I love about your work is that you create that tension between the painterly quality and the image.

J: My worldview isn’t defined very well. I try to do tighter stuff but it doesn’t work. I would love it if I could do a Van Eyck. But I think it doesn’t mesh with what reality is.

D: How so? MORE

February 10th, 2015 by dave dorsey

This story in the Sunday Times seems like a brief scenario from a Kurt Vonnegut novel, as he might have imagined the world decades into the future. A high-tech, high-security warehouse where art can be stored and never need to be moved ever again, while traders buy and sell it at their computers, capitalizing on fluctuations in price. The physical reality of the artwork ceases to matter or even mean anything, since no one ever needs to see it again. The headline for this report yesterday in the print edition was “Art in Residence” but now, online, it has been improved to “Art for Money’s Sake.” From the article:

The wealthiest Americans have grown wealthier since the Great Recession, and many are investing their wealth in art. Especially with bonds and other assets offering rock-bottom yields, the art market — where reports of record-high sales now emerge regularly — has an obvious appeal. According to a survey last year by Deloitte and ArtTactic, an art-research firm, 76 percent of art buyers viewed their acquisitions as investments, compared with 53 percent in 2012. And with more collectors viewing art as a financial investment, storage can become an artwork’s permanent fate.

Largely hidden from public view, an ecosystem of service providers has blossomed as Wall Street-style investors and other new buyers have entered the market. These service companies, profiting on the heavy volume of deals while helping more deals take place, include not only art handlers and advisers but also tech start-ups like ArtRank. A sort of Jim Cramer for the fine arts, ArtRank uses an algorithm to place emerging artists into buckets including “buy now,” “sell now” and “liquidate.” Carlos Rivera, co-founder and public face of the company, says that the algorithm, which uses online trends as well as an old-fashioned network of about 40 art professionals around the world, was designed by a financial engineer who still works at a hedge fund. The service is limited to 10 clients, each of whom pays $3,500 a quarter for what they hope will be market-beating insights. It’s no surprise that Rivera, 27, who formerly ran a gallery in Los Angeles, is not popular with artists.

February 8th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Onion on a Carved Table, oil on linen

If you wanna kiss the sky better learn how to kneel. –U2

I posted a picture of Onion on a Carved Table a while back in a state of trepidation right before I started work on the onion, which I’d saved for last. In the post I talked about how I had to deal with the anxiety of tackling that onion skin. I worked through it, and I’m happy enough with the results that this will be in the two-artist show in March at Oxford Gallery.

I’m at the same point in a larger and more involved painting right now, hoping to finish it in time for the show, as well as submit it for consideration for the Finger Lakes Exhibition at Memorial Art Gallery. The current painting is completely done except for its most complex object, in the foreground, an ornate wine bottle holder that is more or less a family heirloom, which sits, in the picture, on the countertop in our kitchen, with the sink behind it. It is slightly tarnished silver, and capturing the way that surface shines and also doesn’t quite shine in places is enormously challenging, partly because there isn’t a flat point anywhere on the surface of that metal cup, embossed with tiny grapes and pears and vines. I woke up a couple nights ago at 2:30 and couldn’t get back to sleep, which hasn’t happened much this winter so far, so I came downstairs and looked at the progress on the painting and felt an impulse to toss it out (which must overcome any painter at some point). I didn’t, but sat down in the artificial light and worked on it for two hours, long enough to feel that I may manage to complete it satisfactorily by the end of the month. At the end of February I will have invested two months of daily work into this painting, seven days a week, longer than I’ve put into any previous work. Essentially, right now, it’s more a matter of will and desire than skill: if I can work quickly enough on the first coat of paint and then slowly enough on the successive modifications to it, within the time left to me, it will come together. But that’s more a question of character, focus, determination and perseverance–as well as an ability to suppress the anxiety that two months of work will end up wasted. It won’t. But, even if its satisfactory, the painting might not be exactly what I’d hoped or what I know I could have done, and that’s almost as discouraging as the prospect of giving up.

My familiarity with this kind of inner test of tenacity is why two recent movies about the creative process moved me so deeply: Birdman and Whiplash. I didn’t think Birdman could be equalled for the way in which it portrayed the pain of creative effort, and the joy of its fulfillment. That link between the pain of struggle and an ability to be joyful as a result of it is what I heard in my recent rereading of Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy where he had already begun to suggest how art can be a counterforce to nihilism. It can reconcile you to suffering and transform it into joy. A little painting, as much as a Greek tragedy, can be a way of affirming that joy in life as a whole, with all of its unavoidable suffering and tragedy. This may sound a little pompous in relation to worries about how to paint a wine bottle holder, but when you are in that state of doubt about your ability to create something that does affirm the joy of appearances, the prospect of failure can feel excruciating. On top of whatever struggle you happen to be going through in your non-painting life–which was Nietzsche’s real subject, the agonies of life itself. Which is where Whiplash–to get back to my point–may have surpassed Birdman in the way it shows how extreme creative effort is willing to put up with any level of sacrifice, and those stakes are raised to harrowing levels in the movie, before the drummer can break through to something greater than what he’d ever been able to do, because joy was waiting there. Even if that joy is nothing but your own response to having done exactly what you’d hoped and, even so, still feeling more than pleasantly surprised by the results.

I’ve got a lot of work left to do before I get there. Six weeks in, this is the hard part.