Archive Page 29

December 9th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Marching NYC, 1943, Arthur Leipzig, Harold Greenburg Gallery

From New York Times, Dec. 5, via Walt Thomas:

To look at these pictures today is to catch intimations of the evanescence of both youth and a city. In his 1995 book, “Growing Up in New York,” Mr. Leipzig called himself “witness to a time that no longer exists, a more innocent time.”

“We believed in hope,” he wrote.

He began photographing New York children in the early 1940s and continued, off and on, into the mid-1960s. He said his inspiration was “Children’s Games,” a 1560 painting by the Flemish master Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Mr. Leipzig was intrigued, he said, that the games played in Renaissance-era Flanders were similar to the ones he observed outside his window…

…At the Photo League, Mr. Leipzig studied under Sid Grossman, who urged him to apply intuition to his growing knowledge of composition and technique. At the beginning of the course, Mr. Grossman sent him to MoMA three times until he finally reported being moved by a painting, a Picasso.

“Now we can begin to work,” Mr. Grossman said, according to Mr. Leipzig in his 2005 book, “On Assignment.”

December 8th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Self-Portrait c.1799 by Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775-1851

From a friend who listens to Mark Kermode’s podcast, which I do as well, but haven’t had time for it in a while: “Kermode said regarding Mr. Turner that he has never done such a positive review of a movie and yet had so many negative responses to the movie and his review.” Below is a passage from his review in The Guardian which ended with this line, ” . . . this (is an) awards-worthy portrait of a man wrestling light with his hands as if it were a physical element: tangible, malleable, corporeal.”

While his art engages, Turner’s personal life is depicted as increasingly insular and alienated, particularly in relation to the women who fall into his selfish circle. An early abrasive encounter with Mrs Danby (Ruth Sheen), by whom he has fathered two neglected daughters, establishes the artist as cruelly unwilling to acknowledge his adult responsibilities, preferring to be pampered by his own father rather than shoulder the burdens (and bereavements) of paternity. Meanwhile, housekeeper Hannah (Dorothy Atkinson, strong yet pitch-perfectly pitiable) dutifully accommodates Turner’s random needs for sexual relief, her own unspoken affections unmatched by his physical advances, which have the character of an assault. Brothels are visited for inspiration; the corpse of a drowned woman fires a feverish creative urge. Only in his relationship with Margate widow Mrs Booth (Marion Bailey) does Turner seem able to make an intimate personal connection.

For all its evident admiration of his work and legacy (Turner refuses to sell his paintings for a handsome £100,000, insisting that they will be left to the nation), this is also an honestly unsympathetic portrait of the artist as an aging man. On the canvas there is great beauty, while in his life there is ugliness aplenty.

Can’t wait to see it, the beauty and the ugliness both. The friend who called my attention to this also questioned my notion that loving a particular artist’s work is a kind of friendship with that artist–that the work conveys to you the man or woman who made it. There’s a crackpot theory that Walter Sickert was actually Jack the Ripper, and I agree that you can’t get to know Sickert quite well enough through his work to intuit that he liked to kill his models. What you do get to know, in a global way, through an artist’s work is the nature of that person as an artist: which involves a whole range of intuitions beyond what an artist thinks he or she is doing while creating a work of art. My love of Louisa Mattiasdottir’s work doesn’t tell me anything about how she behaved when she wasn’t painting, but all of the aesthetic choices she made in each painting, intentionally or not, consistently show me a complex set of perceptions that hang together in a way that adds up to her vision of the world. It adds up to who she is, as a painter. I don’t need to enumerate all the qualities her choices embody: intense and sustained emotion in an austere landscape, the ability to see the beauty of a particular sweater or a cluster of sheep (if that horizontally striped sweater was wool, who knows, there’s even more going on there maybe . . . ). In admiring her work, I have the equivalent of a friendship with someone who was able to see the beauty of simplicity and constraint, both in the Icelandic climate she apparently loved and in the way she painted. When I look, say, at Basquiat’s work, I see something almost entirely the opposite, and I find it unfriendly, even though many others see childlike exuberance in what he did. That doesn’t mean I think the work is bad. I just don’t have much affinity for it, and since I’m not a professional critic, I don’t need to know more than that.

Turner’s an interesting test of this friendship theory. I’m good friends with him, in his identity as a painter, but maybe I wouldn’t want to spent much time with him over a pint. Though I’m not sure I’d rule that out. I think artists are their best selves while painting, or at least their most effective selves, and that’s the person I want to spend time with and get to know–through the painting, not through the biopic. And what I get from a painting or a body of work is as complex and subtle and partly subconscious as what I gain through actual friendship with the people around me in my non-painting life. It’s holistic, not conceptual.

December 6th, 2014 by dave dorsey

I don’t think Artsy wants to eliminate this.

Following up on my last post, about Artsy, at ArtSlant there’s an interesting rumination on whether online exhibitions of art can ever replace the experience of seeing work in a physical space. I think it’s a misunderstanding of what Artsy is attempting to do. It might occasionally enable people to give up brick-and-mortar exhibitions, but that isn’t the point. It’s more of an attempt to enable people to find exactly what they want in art and then track it down in the physical world, if they like. It doesn’t appear to me that Artsy is trying to replace galleries and museums, but rather give people a way to connect more effectively with them. You can read “Do We Need Galleries Anymore” here at ArtSlant. The writer also mentions Walter Benjamin’s views on the “aura” of a work of art, which can be encountered only by being in the presence of the work itself, but in my reading of Benjamin, it seemed that he was quite happy to see the artwork’s spurious (in his view) “aura” disappear in favor of mass access to art, through mechanical reproduction. So he would support online exhibitions and access, and be pleased to see galleries disappear. He was basically a Marxist who recognized that the art business was a mainstay of capitalism: reproduction of works would make them accessible to anyone, regardless of income. I like the notion of making art accessible to anyone, but that doesn’t mean that the original would lose its value, neither in its “aura” nor in its economic value. John Berger was dreaming when he took Benjamin’s view and went on to say that “the modern means of production have destroyed the authority of art. For the first time ever, images of art have become ephemeral, ubiquitous, insubstantial, available, valueless, free.” Digital images of them have achieved that status, but not the work itself. In other words, everybody wins: those who want to see the work but can’t afford to do that in person, or own it, and those few who can own the original as well.

December 4th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Jon Pestoni, Windshield, 2014, from the Artsy overview of Art Basel

I’m finally recovering enough time and attention to sit up and look around after one of those months of needing to neglect everything I thought I needed to do–but which I guess I didn’t need to do, since it didn’t get done. Such as writing this blog. Still, it felt as if I were goofing off, when I was actually busy getting through November. I hate that: busy but feeling like a slacker. But December is here and I can see a bit beyond my To Do list. One of the first things I saw this morning was Artsy, a new website and organization that looks poised to do something extremely useful (probably, it’s already doing it, and I’m way behind the curve, but they are hiring a lot of people, so that seems at least semi-poised . . .) It appears to be devoted to giving people a central place for following what’s happening in art and maybe finding ways to buy some of it or simply learn more about it. The website design is beautiful, simple, sophisticated, and friendly, If I’m understanding it properly, among other things, Artsy wants to use algorithms to make it easier to identify art that might be of interest to you and see connections with other art that might not have been obvious before. And follow nearly anything or anyone connected to the making or exhibiting or sale of art. That’s the key: a combination of the best elements of Pandora and Twitter and Spotify and Instagram. It can help you stay on top of what’s happening at exhibitions and art fairs, be a sort of concierge for collectors, and it offers an iPhone app that even allows you to organize art on your phone and serves as a guide for any art fair Artsy hosts.

One thing that comes through, this isn’t your typical little start-up. I don’t MORE

December 1st, 2014 by dave dorsey

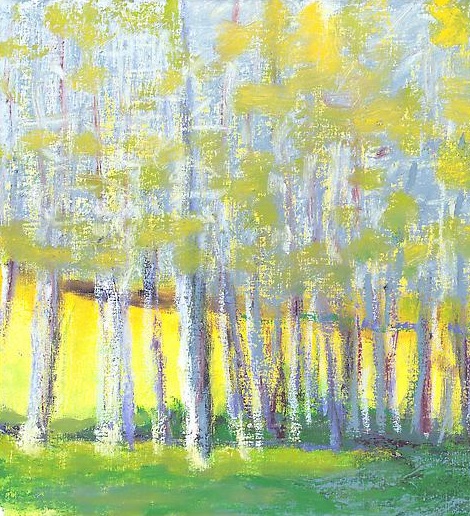

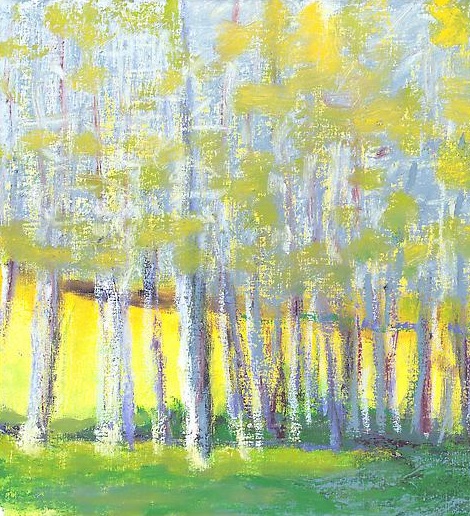

Growing Out of Dark Green, Wolf Kahn, oil on canvas

Popular and profound would be the grail. Easier said than done, but this is nice to hear:

From Tracey Emin’s unmade bed to Damien Hirst’s diamond-studded skull, the work of Britain’s avant garde artists has been lauded and derided down the years in almost equal measure. But now one of the country’s leading arts figures is to launch a ferocious attack on work that “rejoices in being incomprehensible to all but a few insiders”.

In a lecture on “the purpose of the arts today”, to be delivered today in London, Julian Spalding, a former director of three of Britain’s foremost museums and galleries, will say that the public purse should only fund work that is “both popular and profound, as truly great art is”. He will also criticise the supporting of works that appeal “to a self-congratulatory in-group”.

— The Guardian.

November 30th, 2014 by dave dorsey

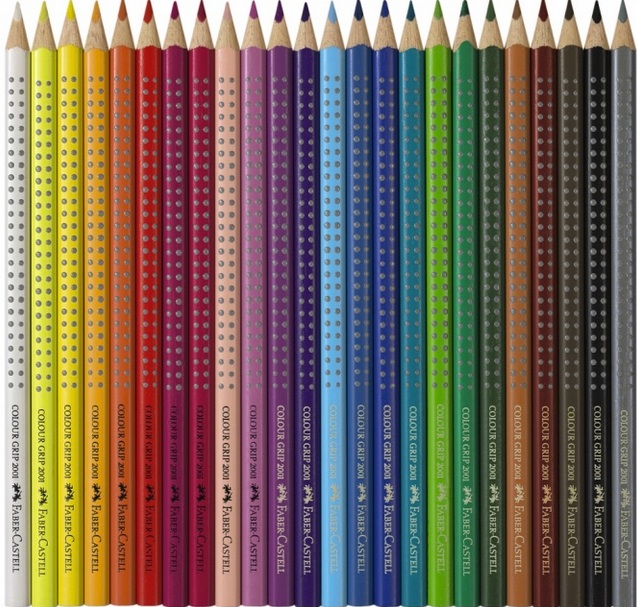

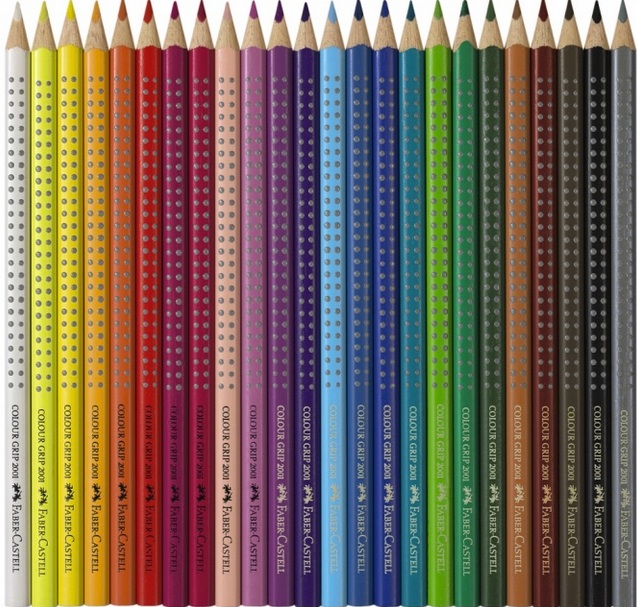

The Path 28, Bill Santelli, prismacolor on paper

About a month ago, I spent a couple hours at our Barnes & Noble’s Starbucks here in Pittsford talking with Bill Santelli, a local artist about my age who is also represented at Oxford Gallery; he does some fantastic abstracts and sells more work than most artists I know, including me. We got onto the subject of being “an artist” as opposed to simply being a painter. I told him I’ve never wanted to be “an artist”; I just want to paint. The idea of being famous or having some recognized role in the “art world,” either as a painter or a writer, feels odd, maybe even a little uncomfortable. I like the feeling of producing satisfying work, but I feel at home in a sort of creative isolation, for some of the same reasons I avoided getting a degree in fine arts. I want to pick my influences. I still distrust much of what’s considered interesting now in the art world, as I was decades ago, and I belong to the school of thought that people become what they behold, or at least MORE

November 17th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Still Life with Lemons, George Braque

Over the past year, more and more, I’ve been involuntarily daydreaming as I paint, in a way that reminds me of what Gaston Bachelard talks about in The Poetics of Space. It’s an idiosyncratic book, beautifully evocative and almost impossible to classify, though it’s often considered a work of philosophy because of its approach to something that sounds absurdly limited: what happens psychologically and emotionally when a person encounters certain kinds of space. It explores how people experience rooms, forests, shells, corners, closets, drawers—and how different the shapes and volumes of these spaces evoke entirely different kinds of dreams. For him, various environments relate in specific ways to the human body and the way people actually inhabit or employ different spaces comes to take on multiple meanings. For him, space is essentially a state of mind rather than the staging area for travel and physical measurement. As Bachelard says in his introduction, the phenomenological approach of the book requires the reader to simply pay attention to how the experience of space can enlarge an individual’s receptivity to new imagery. He puts aside any inherited philosophical or psychological theories and simply examines what’s happening, in human terms, by paying attention to this own encounters with space and how it opens up a state of reverie, a daydream. Different shapes and sizes of space unlock different kinds of dreaming, a treasury of moods, feelings, and mental images. I think what he’s actually doing is elucidating how poetry and painting evoke a sense of a world.

As you read the book it inspires the kind of daydreaming he refers to MORE

November 14th, 2014 by dave dorsey

A three-part show about the human and animal body (heads, arms and legs, and skulls) opened at Manifest–I wrote about it two posts ago–and this remarkable gallery in Cincinnati drew 293 people to the reception. (The email from Manifest to participants was specific about the number, didn’t round it up to “around 300”, which is testimony to the integrity of this gallery and its programs.) Even without the upward rounding, that’s quite a turnout, for any gallery, anywhere. I couldn’t be happier to have a painting in the show, and I have pictures of how it looks (above, for example) thanks to the team at Manifest, who sent shots to all the artists chosen for the shows.

A three-part show about the human and animal body (heads, arms and legs, and skulls) opened at Manifest–I wrote about it two posts ago–and this remarkable gallery in Cincinnati drew 293 people to the reception. (The email from Manifest to participants was specific about the number, didn’t round it up to “around 300”, which is testimony to the integrity of this gallery and its programs.) Even without the upward rounding, that’s quite a turnout, for any gallery, anywhere. I couldn’t be happier to have a painting in the show, and I have pictures of how it looks (above, for example) thanks to the team at Manifest, who sent shots to all the artists chosen for the shows.

Also, the program’s 4th International Painting Annual has just been published (my work was included in it as well) and will soon be available for purchase here. About the annual, from the Manifest website:

about the INPA 4

For the INPA 4 Manifest received 1560 submissions from 563 artists. The publication will include 125 works by 92 artists. Essays by Philip Gerstein and Laura Grothaus will also be included.

Eleven professional and academic advisors qualified in the fields of art, design, criticism, and art history juried the fourth International Painting Annual. The process of selection was by anonymous blind jury, with each jury member assigning a quality rating for artistic merit to each work submitted. The entries receiving the highest average combined score are included in this publication.

November 12th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Detail of background, in progress, from my most recent still life

To continue the train of thought from my last post, I’m working on a modest still life, very simple, painting it at Goldilocks speed, not too rushed but not too cautious, either. If I can generalize an area of varied color into a single hue, I’ll do it, and save the detail work for later, or leave it, or I might linger as long as it takes on certain details. While I’ve been working on this painting, my mind has felt restfully attentive to the quality of the paint I’m applying as much as the image I’m trying to create. I’m working from a photograph I took of a small pewter sugar bowl in our kitchen, and I’m sticking to the narrow depth of field in the shot, which blurs the background slightly. It’s my version of photorealism, though it won’t pass for a photograph up close. I’m simply being straightforward about the artifacts of a shot taken at a certain aperture setting. I almost always use my own photography when I paint an image, sometimes working from multiple shots of a subject in order to get what I want. I had a conversation recently over lunch with Rick Harrington about visibly “pushing paint around.” Rick’s sense was that being faithful to a photograph was antithetical to his love of how paint feels as you apply it and how paint is what a painting is really about. Working from a photograph feels constraining to him, and takes his focus away from the paint itself. Clement Greenburg would approve. I went away feeling as if I disagreed, though not entirely, but without being able to pin down why the conversation left me ambivalent.

I’m happy if I’m working economically, getting more out of the paint than I seem to be putting into it. I keep the process as simple-minded and transparent as I can. The painters I usually respond to most enthusiastically show me exactly what was happening as the painter worked: everything seems to be there on the surface in Fairfield Porter or Neil Welliver or Jenny Saville, which makes the final result so much more remarkable when the image clicks into place, despite how little precise detail the painter is actually rendering. You can track their effort and you can see how they did what they did, though when you stand back you see more, it seems, than the effort they invested. There are no tricks in the magic act. It’s just paint on a surface, and yet it’s also a scene that evokes all sorts of reactions as you forget that it’s paint. The tension is there between seeing the paint and seeing the scene, and the more I can see how simply and directly the painter created the image, the more interesting the tension between paint and image becomes.

Sometimes, for me, this means being very true to the source MORE

November 4th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Face First. Reed Govert’s oil portrait in the current exhibit at Manifest.

I had lunch with a couple friends a couple weeks ago, one of them fellow painter Rick Harrington. We had an interesting discussion about the importance of paint. Two painters talking about paint. Shocking, isn’t it? Rick was expressing his feeling that working from photography inhibits him and has a tendency to turn his attention away from paint and more toward fidelity to the image, the effort of duplicating a camera’s lifeless, flat image. (I disagreed that this is what a camera always gives you, though it’s often true of landscape photography, and Rick paints mostly outdoor scenes and landscapes.) Behind his reservation was the commonly held assumption that working from a photograph becomes an effort to simply copy the photograph rather than using it as a starting point, a fixed reference for doing something based on it. Often that effort can be nothing more than capturing a hyper-realistic duplicate of what the photograph shows, but usually it means altering quite a bit of the shot in subtle ways, or even radical ways. And sometimes it means combining half a dozen shots into a single image. But Rick was right about how, while working from photography, there’s a temptation to slowly inch your way across a canvas, perfecting each square inch as a replica of the corresponding inch in the photograph. (I think there’s pleasure and there can be some big rewards in doing that, but I understand what he’s saying. That kind of slavish obedience to the photograph can rob the painting of life and energy.)

I kidded him about being a brushwork fascist, but I came away MORE

October 25th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Girl with the Banksy Accessory molested in Bristol.

A new mural by elusive graffiti artist Banksy has been vandalised just 24 hours after it appeared on a wall in Bristol, his hometown. Tenant Ellie Morgan . . . said: “It’s a real shame and a bit annoying. Someone just snuck down, did it and then snuck off.”

Wait, what? Isn’t that Banksy’s M.O.?

Pop quiz, multiple choice: 1. Turnabout is fair play. 2. What goes around comes around. 3. Hoist by one’s own petard.

October 23rd, 2014 by dave dorsey

Cow, oil on linen, 18.5 x 37″

I was happy to get an email a few days ago informing me that my still life of a cow skull will be shown along with ten other skull paintings in Losing Your Head at Manifest, in Cincinnati. I was startled at how small the selection was for this show, given the typical flood of entries, with only nine artists exhibiting:

Thank you so much for participating in this process and for your patience! Our jury for this competitive exhibit resulted in the final selection including 11 works by 9 artists. We received a total of 340 entries from 131 artists. Your exhibit is currently planned to be presented in our North Gallery, and it promises to be quite stunning!

I have Lauren Purje and Susan Sills to thank for the inspiration behind the three skull paintings I’ve completed in the past year and a half. Lauren challenged me to try a human skull–and the biggest challenge turned out to be simply getting my hands on one, which I’ve written about before. Once I’d completed and shown it, Susan stepped up and offered to loan me a baboon skull, which she’d come across on a trip to Africa, and gave me outright the cow skull I used for the painting that will be shown at Manifest. The baboon painting just came home from a show at Minot State University, and the human skull painting arrived home yesterday from the Tallahassee International at the FSU Museum of Fine Arts. These vanitas paintings are uniquely challenging but also uniquely rewarding: conveying the complexity of the surface of a weathered, aged skull, discolored from time in the soil, brings an unusual sense of fulfillment when it turns out well.

October 20th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Bay of Sanary From La Cride, 1938, oil on canvas, 23″ x 28″

This image comes from an exhibition catalog published by Tibor de Nagy gallery for a show of Edwin Dickinson’s work in 1996. It arrived last week after I found it online, in new condition, with several good color reproductions of his work, though not as many as I’d hoped. It includes an appreciation by the poet Mark Strand, whose writing about art has been included in a number of art books I’ve bought over the years:

Edwin Dickinson may be one of the least known and least appreciated twentieth-century masters. The reasons probably have to do with the reticence of his best paintings–the quick, improvisational ones he called “premier coups” or “first strikes.” These small, gestural canvases manage, with uncanny ease, to combine airiness and precision. In painting after painting we experience a rightness of scene, a simplicity and directness in suggesting, say, the haze of a summer’s day, or the damp dispersal of seaside light. There is a softness about his paintings that seems the visual correlative of affection, an immediacy that seems a form of surrender to the view at hand. Dickinson’s scrupulous attention to atmosphere, to the feel and prescence of light, to what is most ephemeral in our daily lives, give his paintings an elegiac cast. They are intimate depictions of nature at its most elusive and beguiling.

From the Brooklyn Rail:

Throughout his life, Dickinson credited (Charles W. Hawthorne, an underrated realist painter) with teaching him “That plane relationships (i.e., subtly shifting tonalities) are more representable through comparative value than through implications of contour.”

From the catalog:

Anyone who wishes to elucidate the art of Edwin Dickinson (1891-1978) is confronted by a stubborn paradox: the painter developed and mastered two apparently contrary modes of expression, and skillfully mediated between them for more than fifty years. Dickinson’s first way of working was manifested in large visionary canvases, for which a painstaking understanding of three-dimensional design was demanded. Created from memory and imagination, each elaborate painting could take years to construct, and the artist never deemed any of them completed to his satisfaction. Dickinson’s second principal means of expression was manifested in several hundred landscapes distinguished by their air of spontaneity, liquid fracture, and vivacious handling. Painting directly from nature and out of doors, these canvases were created au premier coup, mainly in Western New York, Cape Code and rural France, each in one sitting. After a session of three or four hours, Dickinson considered a picture done and walked away from it . . .

October 17th, 2014 by dave dorsey

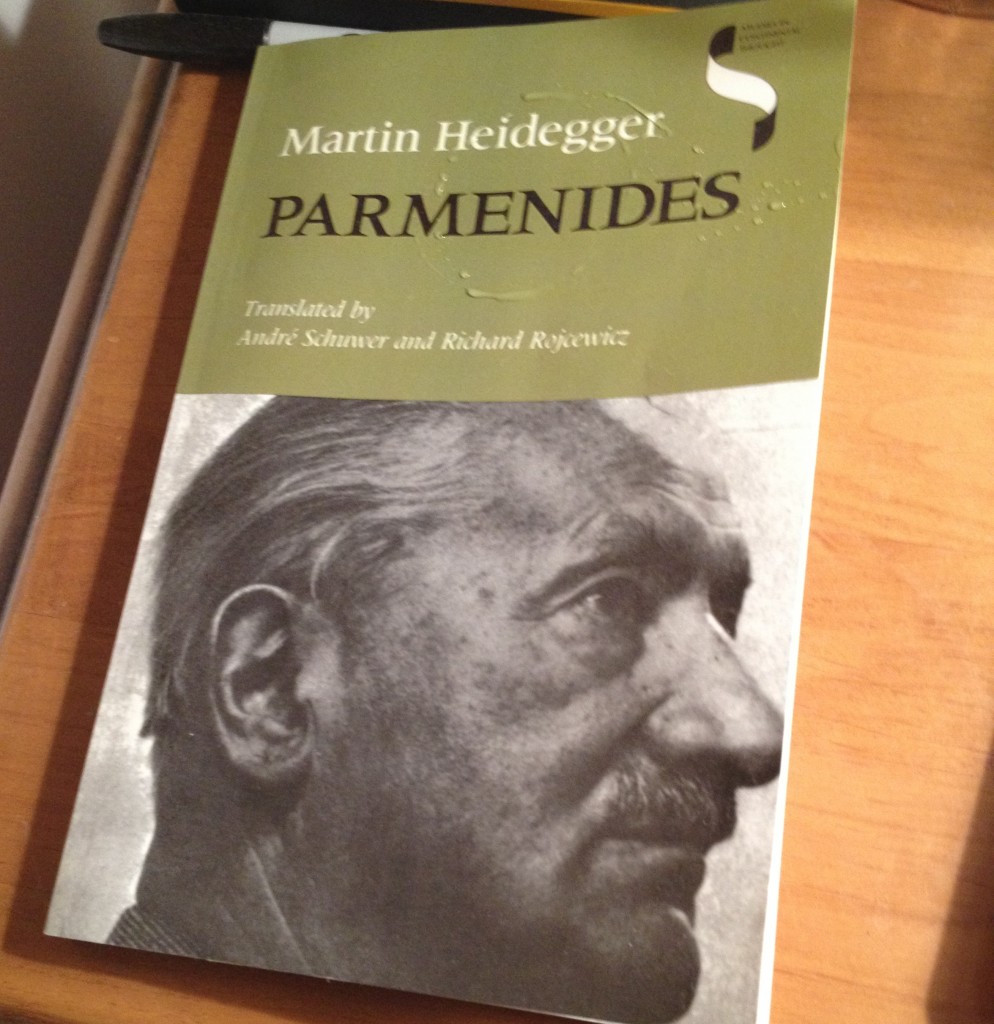

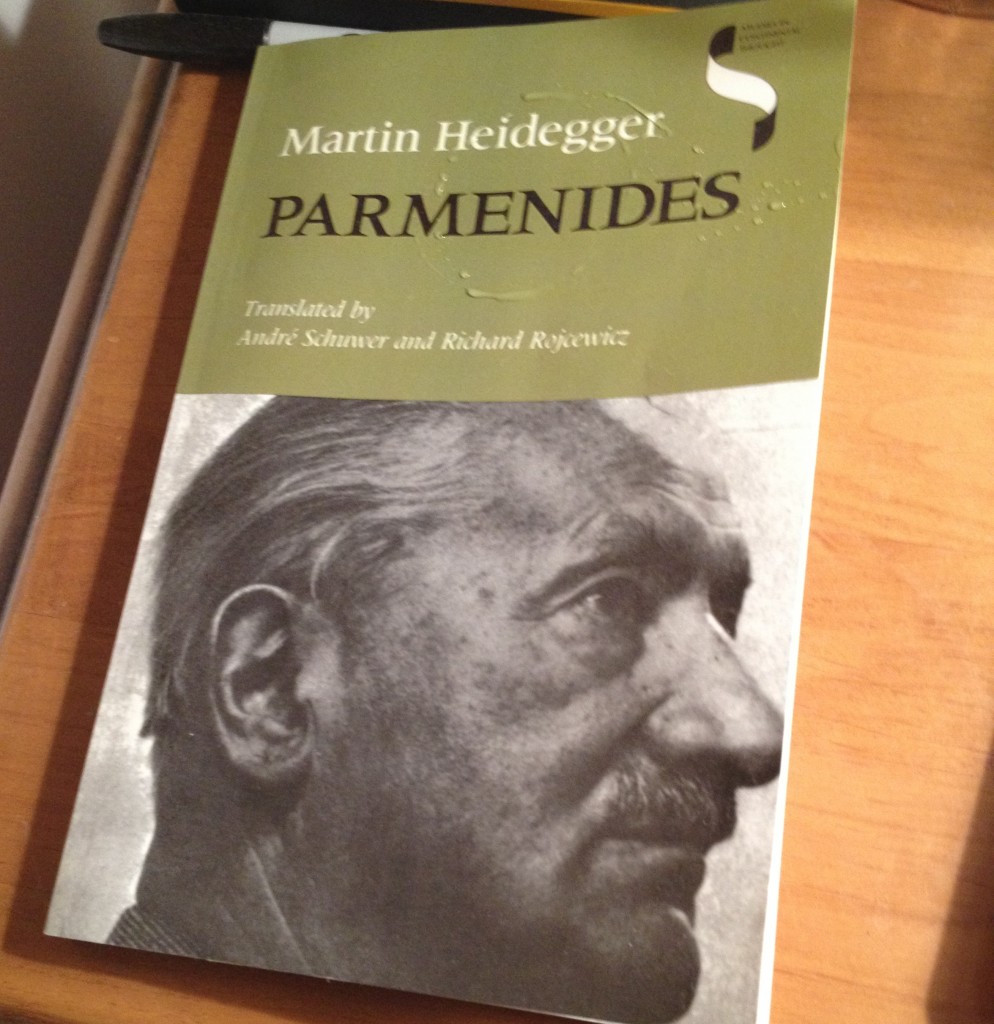

Some current light bedside reading.

This past summer I was driving from Rochester to Chautauqua, to spend a few days helping Peter Georgescu put together a new book proposal, which turned out to be productive (and gave me a chance to work with Andrew Terrell, a very young former White House staffer who seems to know everything that’s going to happen in Washington before it actually happens.) On my drive, somewhere in the Southern Tier, using a podcast app on my iPhone, I stumbled onto a program that has since become something I regularly listen to while painting: Entitled Opinions, by Robert Harrison, a professor of French and Italian at Stanford. It’s an intellectual oasis, a golden island of conversation that constantly makes me whisper, yes, exactly to myself while I’m absorbing it. Its archive makes available ten years of programming, a buried treasure. I can’t wait to make my way through it. Harrison’s professorial post doesn’t reflect his depth of learning in a wide variety of fields: either he’s a very quick study or he retains everything he’s investigated from decades of research and reading. Many of his guests also teach at Stanford, or Berkeley, or at another school here or in Europe. He’s not only erudite but persists in thinking along lines that have been abandoned by many philosophers these days. As far as I can tell from my layman’s perch, philosophy these days wants to find a safe harbor in brain research, rather than interrogating the mystery of things in a way that does little more than ponder unanswerable questions. These days thinking about consciousness tends to regard it as just one more phenomenon to be objectified, on the assumption that human nature is yet another biological mechanism to be understood and eventually improved upon through some kind of intervention. In the podcast I listened to in the car, a conversation about Heidegger with Thomas Sheehan, the guest and host mentioned at one point a philosophy convention where all the Heidegger specialists huddled in one corner and talked amongst themselves, with little contact with anyone else at the event, an anecdote that made me laugh with approval. Good for them! That image probably offers a clear picture of how much weight Continental philosophy carries these days in American academia.

The discussion with Sheehan, who has a book on Heidegger coming out shortly, was primarily about Being and Time, Heidegger’s most influential book. I never managed to get through it in college, though I studied Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, which grew out of Heidegger’s work. Ever since then, I’ve dipped into Heidegger’s later writing, with special attention to The Origin of the Work of Art. And since I heard this podcast, MORE

October 15th, 2014 by dave dorsey

The World’s Biggest Drawing Festival runs throughout October; you can read more here. You can sample a charming children’s book on drawing/painting/printing like the great artists from The Guardian here.

October 13th, 2014 by dave dorsey

People say that Florence teaches you to see differently — that as the soft light moves across the ocher buildings, you see colors you never noticed before.

People say that Florence teaches you to see differently — that as the soft light moves across the ocher buildings, you see colors you never noticed before.

It taught Kevin Systrom, a co-founder of Instagram, to see differently. He attributes his inspiration to a photography class he took in Florence while at a Stanford study-abroad program about a decade ago. His teacher took away his state-of-the-art camera and insisted he use an old plastic one instead, to change the way he saw. He loved those photos, the vintage feel of them, and the way the buildings looked in the light. He set out to recreate that look in the app he built. And that has changed the way many of us now see as well.

–T.M. Luhrmann, New York Times

October 11th, 2014 by dave dorsey

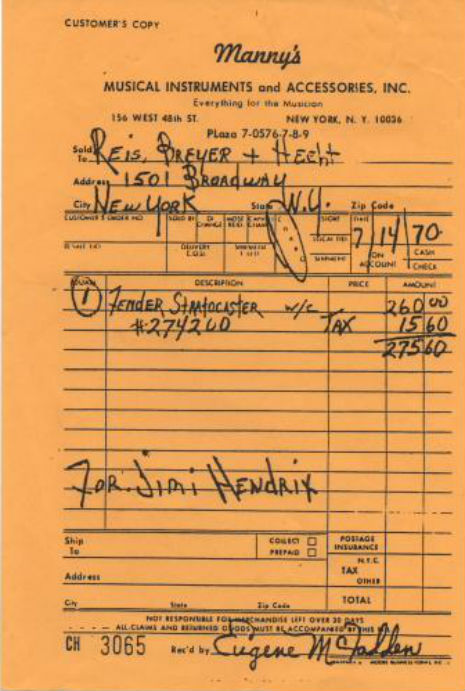

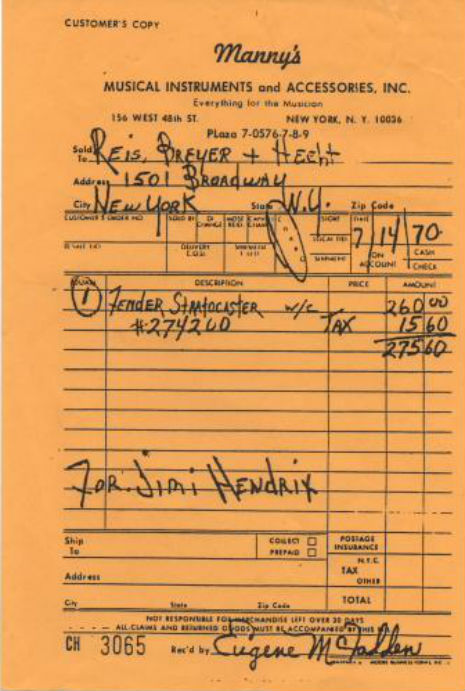

Little did he know he had only a month left to play it.

October 9th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Selfie, Oil on Panel

I’ve begun to have a deeper appreciation for deadlines. I’ve been painting on firm deadlines for a couple years now, first for a two-person show at Oxford Gallery in 2012, then a solo show at Viridian Artists this past summer and now another two-person show at Oxford in March, 2015. This last deadline is pushing me to do things I haven’t done before, such as work on more than one painting at a time, and it’s also motivating me to develop more efficient ways to paint.

There’s a certain optimum pace for developing a painting. Too slow and fastidious, and the life drains out of it. Executed rapidly, it can sometimes come alive in a rare way, but it’s an unreliable and risky way to proceed with something that might quickly fall apart—which are then wasted in a discouraging way on a deadline. When I attempt premier coup work, as Edwin Dickinson referred to it, and I know it’s going well, the propulsive momentum of the work adds a different kind of vitality to the image. The effort gets concentrated into a comparatively brief time, and the life of the marks vibrate with the pressure of that quicker execution. It’s the most difficult way to paint well, because much is at stake and there’s little “going back over.” I read somewhere long ago that Francis Bacon loved tight deadlines. He would do much of his work for a particular show at the last possible minute and hang the paintings still wet. It isn’t hard to believe, given the the way he pushed paint around. For him, it worked. Yet I love, just as much, paintings that take weeks or months to complete, and they convey something far different and more subtle, some hint of what Keats called “solitude and slow time.” I’m attempting to finish examples of both kinds of painting for the show next year. In either case, deadlines are giving me a greater sense of discipline, as well as a wistful sense of how much time I used to have to do other things. (On top of the daily painting, seven days a week, I’m also up early, working on writing projects that bring in the bulk of my income. I paint with the time left free—and I’m able to do it every day.)

I tend to work in successive shifts of three or four hours, with breaks for meals or errands. I’m learning to get more done in each of these windows of opportunity. I calculate exactly how much I need to finish on each day throughout a given month and then track whether or not I’m ahead or behind of my quota. I expect by the end of the work for this next show, I’ll be producing probably twice as much work as I have in the same period of time in the past. One thing I’ve observed, no matter how much I’m enjoying work on a given painting, I procrastinate before sitting down and picking up a brush. Once I do, and once I put down the first mark of the day, it’s as if I’m already at full speed. There’s no ramping up, no acceleration: I’m fully immersed on the step-by-step progress of making the image come to life.

On balance, deadlines are helping me take my work to the next level, not only because it’s making me refine my work methods, but also because there’s no way to adhere to them without bringing the most focused sort of attention to the process. That attention—a heightened awareness of what I see and what I’m doing—is what it’s really all about. It would be nice if I could bring it to my entire life.

October 7th, 2014 by dave dorsey

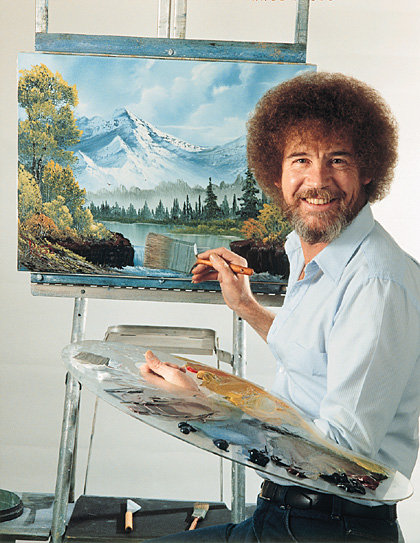

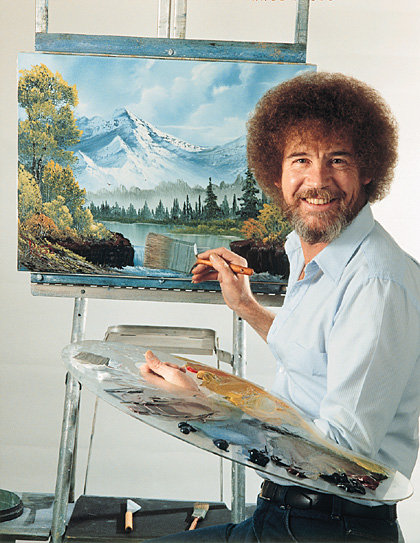

The actual Bob Ross, not needing to sell real estate in Florida.

A friend sent me “Glengarry, Bob Ross” from McSweeney’s. As I read it, I could see Baldwin, in a Malcolm Gladwell wig: First place, my BMW. Second place, a set of palette knives. Third place, penniless immortality.

Get mad, you sons of bitches. Get mad. You know what it takes to paint cozy log cabins that speak the softest parts of the human soul? It takes BRASS BALLS.

The link will yield even funnier lines.

October 5th, 2014 by dave dorsey

“It is a very slow process in comparison with taking the photos and it is the opposite in that you are confined to a small dark room instead of being out and about in the light and the air,” Steinmetz said about doing his own developing and printing. “The darkroom is where I really confront what I’ve been doing, whether I have been successful or not and whether making a print is really worth all of the effort. Doing darkroom work yourself helps you to become a better editor of your work, which in turn helps you be a better photographer when you are out there working. Today’s world is so fast-paced with instant results in so many aspects of our lives, that in comparison, darkroom work seems to be an alien relic from an ancient world.” —Mark Steinmetz