Archive Page 17

July 18th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Chevron Bowl, oil on linen, 12″ x 16″

Chevron Bowl and Red Bartletts will be on view at Minot State University in the Northwest Art Center’s Americas 2017 from August 15 through September 28.

Red Bartletts, oil on linen, 10″ x 18″

Chevron Bowl was included in an exhibition at the New Jersey Center for Contemporary Art late last year. This is the first exhibition for the pears. They are both part of my effort, in parallel with the more highly realistic work I do, to experiment with a faster, simpler, and in some ways more painterly method–closer to Dickinson’s premier coup paintings, as he referred to them. In this work, I’m thinking always of Fairfield Porter, the perceptual painters, and, inevitably, Matisse. The aim is to keep a fairly tight sense of draftsmanship with a greater focus on value and color rather than detail and line–even though crisp delineation is always there in some areas of the work. I was very happy with the results in Chevon Bowl, and loved the outcome with the pears as well, though it ended up being more consistent with what I traditionally have been doing.

July 14th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Breakfast with Golden Raspberries, detail. oil on linen, 22 x 46, 2016.

I was honored to be informed that I won Director’s Special Mention at the Butler Institute of American Art’s 81st Midyear Exhibition for “Breakfast with Golden Raspberries.” I had intended to attend the opening this year, but was sorry to miss it, coming back from California two days later. Hard work is rewarded: it’s probably the most labor-intensive painting I’ve ever done, with some areas that needed reworking repeatedly. From what I can tell, at this distance, it looks like a fine show, and I may get there to see it, yet.

June 29th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Two Flavors (Ice Cream Cone), Wayne Thiebaud 2003

I’ve often talked with Bill Santelli about having personal, felt rules, a set of boundaries for how I paint, which create a skeleton of principles around which to make a picture I want to see–which is my first rule, actually, to paint only what I really want to look at, with almost no other consideration. It’s odd, but I can stray from this rule so easily, for one reason or another, without quite being aware how I’m gradually drifting from the delight of the true path. For a while, Bill tended to push back whenever I asserted this and then began to understand what I meant. This was no surprise since his work operates so obviously in accord with what I was saying; I think it was just that he bristled at the onerous associations he had with the word “rules.” Today, I heard the same kind of idea expressed in an interview on All Songs Considered, put into our larger nihilistic, postmodern predicament of having the license to do anything at all and call it art. It was a comment during an interview with the members of Phoenix in a discussion of the French band’s new album, Ti Amo:

The issue is that there are no more limits, in terms of music. Everything is possible. Most of our time we spend in the studio we spend it to create a frame, just to have . . . limits, so we have something coherent in the end.

All of this seems related to Kandinsky’s idea of “inner necessity,” the desire that impels you to make art in a certain, individual way–and the long search to come upon that feeling of necessity. To discover that internal compass, Phoenix will come up with a single image, like a high concept for a movie, around which to create an album. I loved hearing how the spirit of the new Phoenix album, the aesthetic of its overall sound, was centered on the gestalt, the feel, of ice cream. There was something so Thiebaud about that, to embrace that spirit, especially in Paris, of a particular kind of lush pleasure as a guiding aesthetic for a new album in this era of political vitriol and spurts of terrorist violence. It struck me as a radical affirmation of joy in art, for its own sake–like Matisse cutouts or Agnes Martin’s glowing stripes. That’s a delight to the ears of this painter who continues to paint his share of confection and candy.

We could not have released this kind of record in a period of relative happiness. We needed the darkness to come up with this naive and joyful music. We didn’t control it. It’s just what happened. We write music not really knowing what we’re doing, but when it’s done, we realize . . . we have a safe harbor for ourselves. We have hope. It’s uncontrolled.”

Those words almost sum up what I expect and desire from the unknowing act of painting, naive and joyful and willfully ignorant of whatever others think painting needs to be–how “important” it should strive to make itself–in order for the work, when it’s done, to be exactly what I want to see, even if I’m the only one who’s looking.

June 26th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Spiral Bowl with Flat Screen, oil on linen, 16″ x 24″

I’ll be showing Spiral Bowl with Flat Screen at Xavier University Art Gallery’s “Art at the X” from Aug. 25 through Sept. 22. It’s been a number of years since I’ve shown there, and I’m happy to be joining the exhibition again.

June 13th, 2017 by dave dorsey

The past two years have been a desultory mix of so many obligations that it has been nearly impossible to hew to a daily painting discipline. Typically, I’ve enjoyed two months of fairly uninterrupted work and then faced a month when I might have only a few days available for painting–earning some money as a writer, putting in time as a caregiver for my parents, working on our house, visiting my kids in California. As of this June, though, I’ve been able to paint every day and should be able to stick with this schedule into the foreseeable future, with only some short breaks here and there. It’s put me in a much better mood, in general, though that’s tempered by the fact that I’ve reached a point where I’m more critical of the work I’m doing, as I do it. I keep wrestling with a specter of what I recognize as a hyper-sensitive discouragement about results, when the results are actually perfectly fine because what I’m doing and seeing in the work is part of the evolution, the path. Ironically, I feel as if I’m at a threshold where my methods and skills are such that I can reliably do certain things now that weren’t possible before, so I have to fight an impatience that arises when I’m not surprised by what I’m doing. (I’m still struggling as I go, facing uncertainties, but it’s more within a broader range of confidence, so my success at this or that doesn’t impress me as much.) I need to be patient and do what I know how to do for a while, consolidate what I’ve learned about how to paint, in order to build a body of work over the next couple years–which means I have to fight the impatient urge to push past this stage into something a little bolder. More on that later.

Meanwhile, in an email alert from Open Culture, I learned that I can listen to hours of Joseph Campbell lectures for free now on Spotify. Quelle pleasant surprise. I immediately started listening to his lectures at Cooper Union in the late 60s, and after only a few minutes Campbell got right to the heart of the matter and confirmed that I will have some pleasant hours ahead of me:

One of the problems man has to face is reconciling himself to the problem of his own existence, and this is the first function of mythology is that reconciliation of consciousness with the mystery of being, not criticizing it. Shakespeare and his definition of art where he says, art (or the art of acting,) holds the mirror up to nature. It is a perfect definition I would say of the first function of mythology. When you hold a mirror up to your self, your consciousness becomes aware of its support, what it is that is supporting it. You may be shocked with what you see; or you may be pleased that you become aware of yourself, your consciousness becomes aware of that darkness, that Being which came into being out of darkness and which is its own support. The first function then of a mythology is the reconciliation of consciousness to the foundations of being and the realization of their mystery as something that consciousness is not going to be able to criticize, not even going to be able to elucidate, not even going to be able to name. It is something beyond naming, beyond all definitions, and when that is lost one loses the sense of awe, which Goethe calls the best thing in man. One loses the sense of gratitude for one’s privilege of having a center of consciousness aware of these things.

May 28th, 2017 by dave dorsey

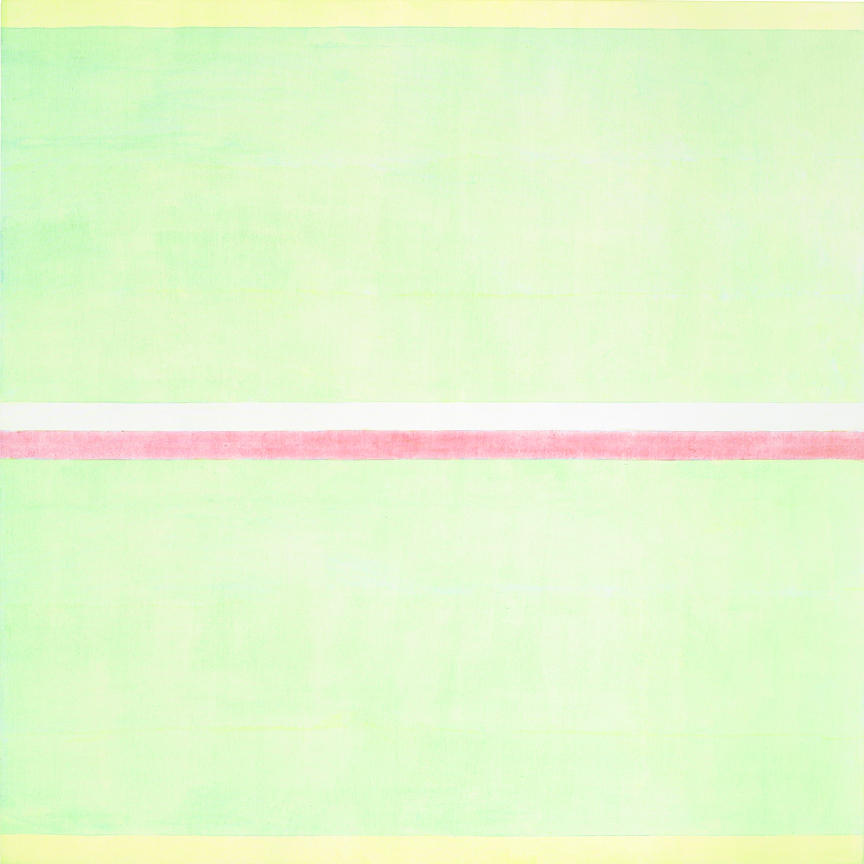

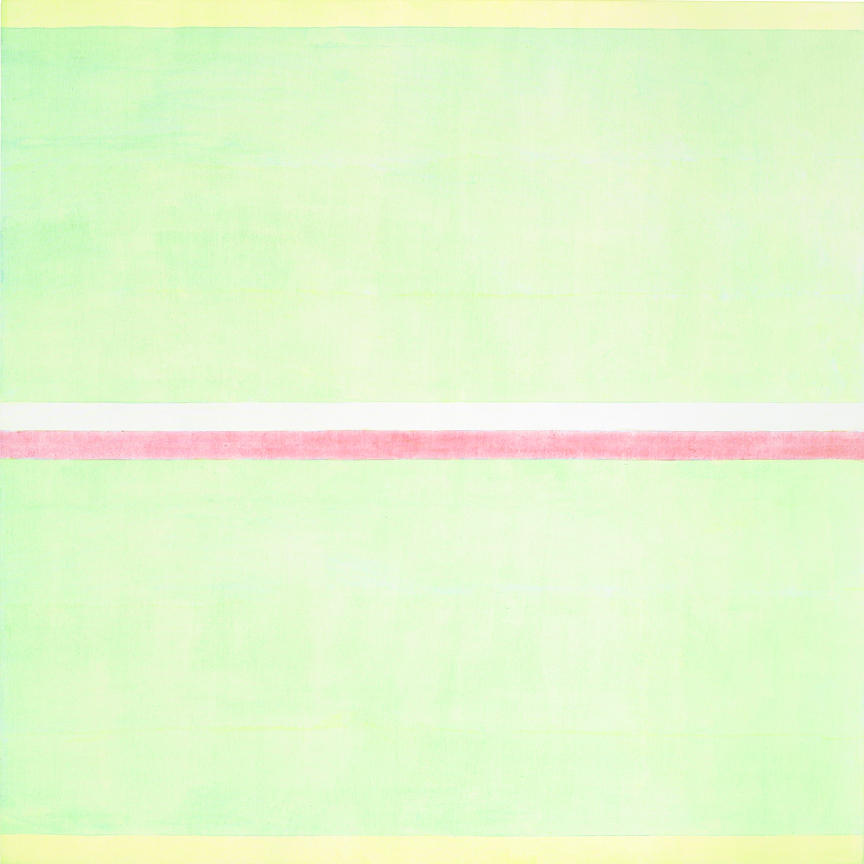

Agnes Martin, Gratitude, 2001, acrylic and graphite on canvas, 60 x 60 inches

Thoughts on how not to think, from Agnes Martin:

The life of an artist is a very good opportunity for life.

When we realize that we can see life we gradually give up the things that stand in the way of our complete awareness.

As we paint we move along step by step. We realize that we are guided in our work by awareness of life.

We are guided to greater expression of awareness and devotion to life.

You must say to yourself: “How can I best step into this state of mind and devote myself to the expression of life.”

You must not be led astray into the illustration of ideas because that is not art work. It is ineffective even though it is often accepted for a short time. it does not contribute to happiness and it is finally discarded.

The art work in the Metropolitan Museum or the British Museum does not illustrate ideas.

The great and fatal pitfall in the art field and in life is dependence on the intellect rather than inspiration.

Dependence on intellect means a consideration of observed facts and deductions from observation as a guide in life.

Dependence on inspiration means dependence on consciousness, a growing consciousness that develops from awareness of beauty and happiness.

To live and work by inspiration you have to stop thinking.

You have to hold your mind still in order to hear inspiration clearly.

May 25th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Introspection, Dario Tazzioli, carrara marble.

I had some fascinating conversations with fellow artists at the reception for Doppelgangers at Oxford Gallery, where Jim and Ginny Hall have assembled another fine group show. It drew a large crowd, and it may have offered the largest number of pieces of any show they’ve ever put together, more than sixty. Many of the contributors took the theme as a pretext for submitting a pair of works, some two- and some three-dimensional, and yet everything seemed to fit perfectly into the available space. The idea of doppelgangers inspired or at least drew some exceptional work that had already been completed. As always, it’s impossible to do justice to everything on view, but again Dario Tazzioli’s sculpture was a magical affirmation that the artistic past is also its present and future. His Introspection, the bust of a young woman with a mane of flowing, wavy hair, carrara marble carved with a hand-turned bow drill—delivered to the show from Italy—stands as a quiet traditional tour de force, a testament to how nothing is off the table in art now. “Anything goes in art” used to mean that Warhol could fill a room with balloons and call it a masterpiece; now it means that the heritage of Donatello can still speak powerfully to a contemporary audience.

Tom Insalaco’s two paintings of faces offer the same lesson in a darker mood. They are the work of a man who has, for decades, been inspired by and driven to honor the Renaissance and baroque periods. He continues to quietly labor at his home studio in Canandaigua, NY, with more than one room turned into warehouses for his past work, all of it deserving a serious retrospective, but as if often the case with brilliant work done in obscurity, no one seems to be knocking on his door offering to revive interest in his remarkable career, which moved over the years from photo-realism to a reverence for the Old Masters. Since last year I’ve been studying and reading about Piero Della Francesca, whose work, especially, toward the end of his life, strikes me as powerfully alive and evocative and stylistically individuated in a completely contemporary way—which again suggests that emulating the mannerists or the Old Masters or the early Renaissance, or any other period, doesn’t need to be even a quasi-ironic undertaking, as it is with John Currin or Kehinde Wylie.

I had a long, probing conversation with Phyllis Bryce Ely about the recent work of hers I’d seen earlier in the day at Main Street Arts in Clifton Springs, NY: MORE

May 7th, 2017 by dave dorsey

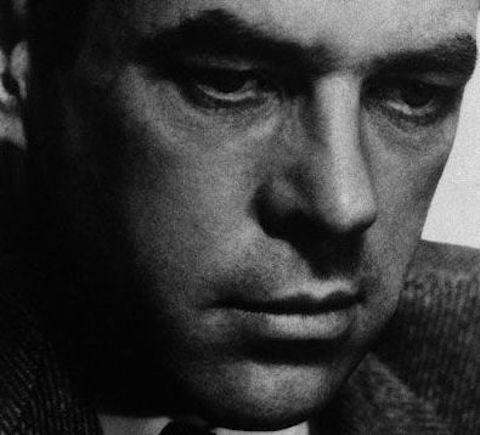

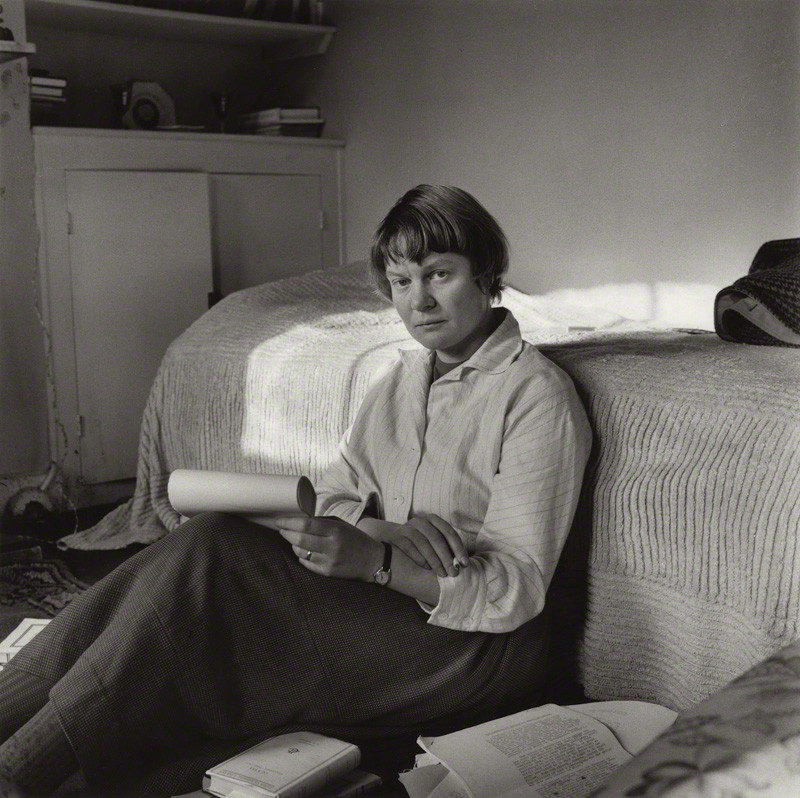

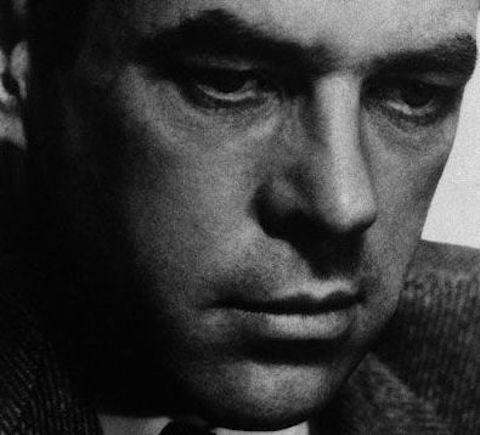

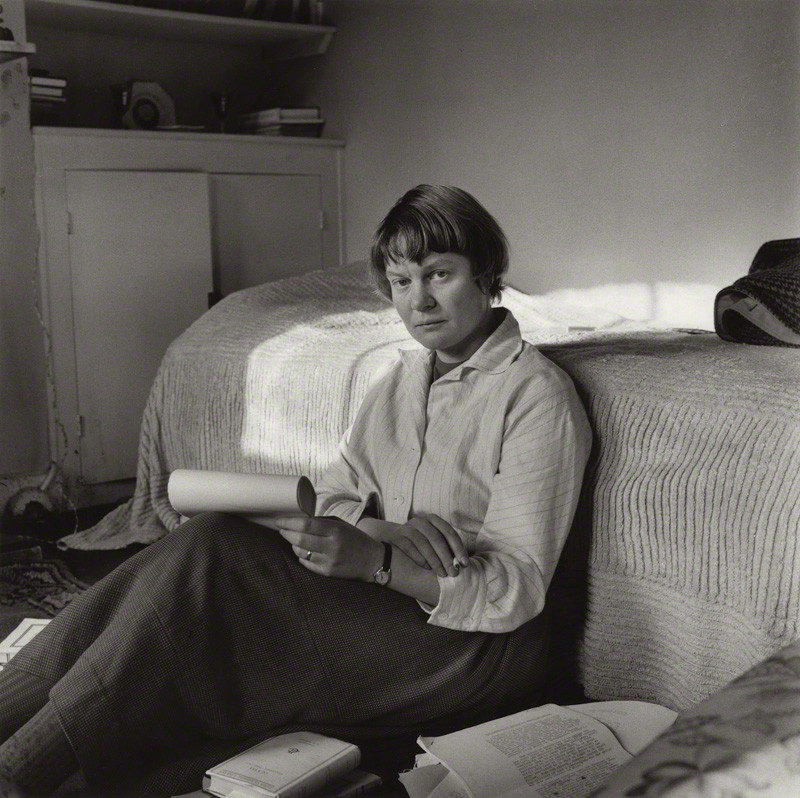

Iris Murdoch, by Ida Kar, 1957 National Portrait Gallery

Iris Murdoch, from Existentialists and Mystics:

Following a hint in Plato (Phaedrus, 250) I shall start by speaking of what is perhaps the most obvious thing in our surroundings which is an occasion for ‘unselfing’, and that is what is popularly called beauty. Recent philosophers tend to avoid this term because they prefer to talk of reasons rather than of experiences. But the implication of experience with beauty seems to me to be something of great importance that should not be by-passed in favor of analysis of critical vocabularies. Beauty is the convenient and traditional name of something that art and nature share, and which gives a fairly clear sense to the idea of quality of experience and change of consciousness. I am looking out of my window in an anxious and resentful state of mind, oblivious of my surroundings, brooding perhaps on some damage done to my prestige. Then suddenly I observe a hovering kestrel. In a moment everything is altered. The brooding self with its hurt vanity has disappeared. There is nothing now but kestrel. And when I return to thinking of the other matter it seems less important. And of course this is something that we may also do deliberately: give mention to nature in order to clear our minds of selfish care. It may seem odd to start the argument against what I have roughly labeled as ‘Romanticism’ by using the case of attention to nature. In fact, I do not think that any of the great Romantics really believed that we receive but what we give and in our life alone does nature live, although the lesser ones tended to follow Kant’s lead and use nature as an occasion for exalted self-feeling. The great Romantics, including the one I have just quoted, transcended ‘Romanticism’. A self-directed enjoyment of nature seems to me to be something forced. More naturally, as well as more properly, we take a self-forgetful pleasure in the sheer alien pointless independent existence of animals, birds, stones and trees. ‘Not how the world is, but that it is, is the mystical.’*

I take this starting point, not because I think it is the most important place of moral change, but because I think it is the most accessible one. It is so patently a good thing to take delight in flowers MORE

April 20th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Breakfast With Golden Raspberries, oil on linen, 22″ x 46″

I was pleased to learn that Breakfast with Golden Raspberries was invited to another exhibition, the Midyear at the Butler Institute of American Art, July 9-August 20. It will be its third event since last fall, after exhibitions at Marin Museum of Contemporary Art and at Manifest Creative Research Gallery. There were almost 900 entries from 313 artists, with 83 pictures accepted.

April 9th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Head of Bodhisattva, Pakistan, Gandhara, 3rd-5th century, gray schist.

As art collectors, John and Mable Ringling fished with a net. And you get the impression that they wanted you to see nearly everything they snared in their trawls through Europe and Manhattan, even though what’s on exhibit at The Ringling in Sarasota is only a fraction of the permanent collection. You’re confronted with a numbing quantity of art in quick succession, but with a recurring revelation of brilliance in every gallery. Those little epiphanies of mastery kept luring me into a sort of Easter egg hunt as I moved from room to room.

I spent a few hours inside the museum on my last full day in Florida last week and came away extremely impressed which much of what I saw and grateful for having the chance to see the Asian wing—a rich little vein of ancient Asian art and antiquities. The exhibit of Cypriot treasures is a profound experience of the past conveying a deep spiritual resonance for any contemporary visitor interested in Asian spiritual traditions. The museum did a beautiful job in giving you an enormous roadmap, as it were, almost as long as the entire Asian wing, showing how Cyprus was positioned so that the Silk Road’s routes converged near the island. Most of the Eastern routes funneled through or around the island and then moved into Europe, therefore Cyprus naturally snagged a lot of the cargo moving from East to West. This show has been as expertly mounted as anything you would see at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—from which Ringling purchased the bulk of the collection in 1928. (One wonders how much of a bargain he might have gotten by waiting a couple years.) The Cypriot exhibit proves that this particular purchase was one of the most amazing and successful casts of Ringling’s net into the sea of world art. He may not have had the cautious and flawless taste of, say, a Duncan Phillips, but as a collector the efficiency of his methods sometimes worked beautifully.

Under the governance of Florida State University since 2000, The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art has become a significant cultural resource—and walking through it now you get the sense that you’re seeing a chrysalis that’s just beginning to open up. You get glimpses of the butterfly’s anatomy, and it’s going to be a while before you see it fly, but the metamorphosis is underway. The challenge facing those who run it now will be how much they need or want to honor John and Mable Ringling’s original intent. In many galleries, the founders created interior spaces that resembled the sort of European rooms where the work originally might have been hung—coffered ceilings in one gallery, red walls, wood paneling and trim, in many—offering an historic replica of aristocratic European interiors. For me these spaces distract from the mastery and brilliance of many individual works. The crimson walls loom around the edges of the paintings. I kept wanting to see particular paintings given a little more room to breathe and to forget the walls the way I would in the neutral white cube of a contemporary gallery. I wondered how much more powerful the enormous, lavish, maximalist cartoons Rubens painted as models for tapestries would have looked in the luminous and neutral ambiance of, say, David Zwirner’s Chelsea gallery. And there were Old Masters—Cranach, Velazquez, and Hals—that towered over neighboring work and would have been better served by being a little more removed from their lesser company. The museum is planning, over the next few years, to completely redesign the way its collection will be viewed—which was part of the pleasant anticipation I felt as I got more and more acquainted with what’s happening there. The curatorial challenge has to be both interesting and frustrating: whether or not to remain as true as possible to what the Ringlings wanted and (if those constraints matter) how to do justice to the full potential of the collection’s best work.

The overall impression you get from the core collection is that Ringling liked to buy his art in bulk to create a major cultural resource tout suite—and his focus on volume suppressed what might have grown into a more selective passion for Old Masters and Baroque art. He seemed to have been following the traditional path of the American capitalist mogul: build wealth by any available means and then elevate (and maybe redeem) yourself in the third act of your life by becoming a philanthropist. J.P. Morgan and Henry Clay Frick perfected this sort of shape shifting by creating what have become two of Manhattan’s cultural crown jewels. Likewise, the Ringling could end up being the pinnacle of Florida’s art museums. It’s one of the greatest virtues of capitalism’s concentration of great wealth into individual ownership: it can leverage world-changing projects, in very short order. Bill and Melinda Gates come to mind, among many others, and Ringling was cut from this same mold.

What’s on view right now is remarkable—for me, the survey of Cypriot Asian objects was the best reason to visit the place. The small Searing Wing, though it’s a slight overview of modern and contemporary work, offered me my first look at a painting by Jon Scheuer, a stunning piece—I’ve loved his work in reproductions but it was impossible to see the sensuous complexity of his brushwork from photographs. Seeing the actual work had a big impact on my understanding of his work. As I wrote to Bill Santelli afterward, Schueler is closer to a Romantic than an abstract expressionist, more Turner than De Kooning. It was odd that photography was prohibited in this wing when I couldn’t find a catalog for what was being shown there—and catalog sales seems to me the only rational argument against photography now, given that the current pandemic of Compulsive Instagram Syndrome seems the best way to bring people into an exhibition.

The most impressive exhibit, by far, though, in terms of the intelligence and scholarship that went into gathering and presenting the show was A Feast for the Senses—a sort of Babette’s Feast of artwork from the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance assembled to show the marriage of sensory and spiritual experience in courtly and religious ritual. It convenes more than a hundred objects from multiple sources: the Morgan Library, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Designed to offer a “multi-sensory experience,” through multiple galleries, the show infuses rooms with scents and background music or bird songs, and a few things visitors can touch. It was put together in conjunction with Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum, and deserved a much longer span of attention than I gave it. You come away from the exhibit with a view of the Late Middle Ages as a period of time much more illuminated by intelligence and wit than one might have thought, and where earthly appetites and the senses were incorporated into religious devotion. It was a fertile period, and in every piece you feel an entire civilization awakening from a long retreat from Hellenic civilization—the doorstep of an explosion in knowledge and creativity that set in motion the events that led to the world we’re living in now.

According to one of the docents monitoring a gallery in the Asian wing, The Ringling recently drew 5,000 visitors in a single day (the adjoining Circus museum has to be a huge attraction as well)—so what’s happening there is certainly working. On my way back to my car in the packed parking lot, I realized how knuckleheaded I’ve been to miss what’s been going on there over the past 15 years. The last time I’d visited in the museum was in the 90s before the current long-term restoration of the institution. I’ll be visiting every time I’m in Sarasota now.

April 5th, 2017 by dave dorsey

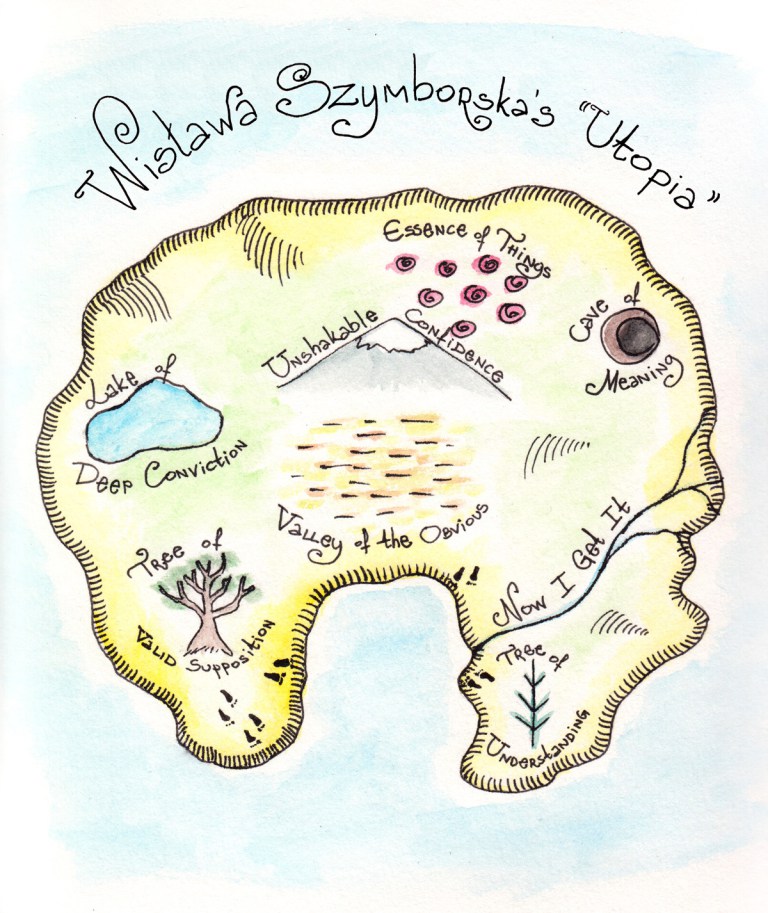

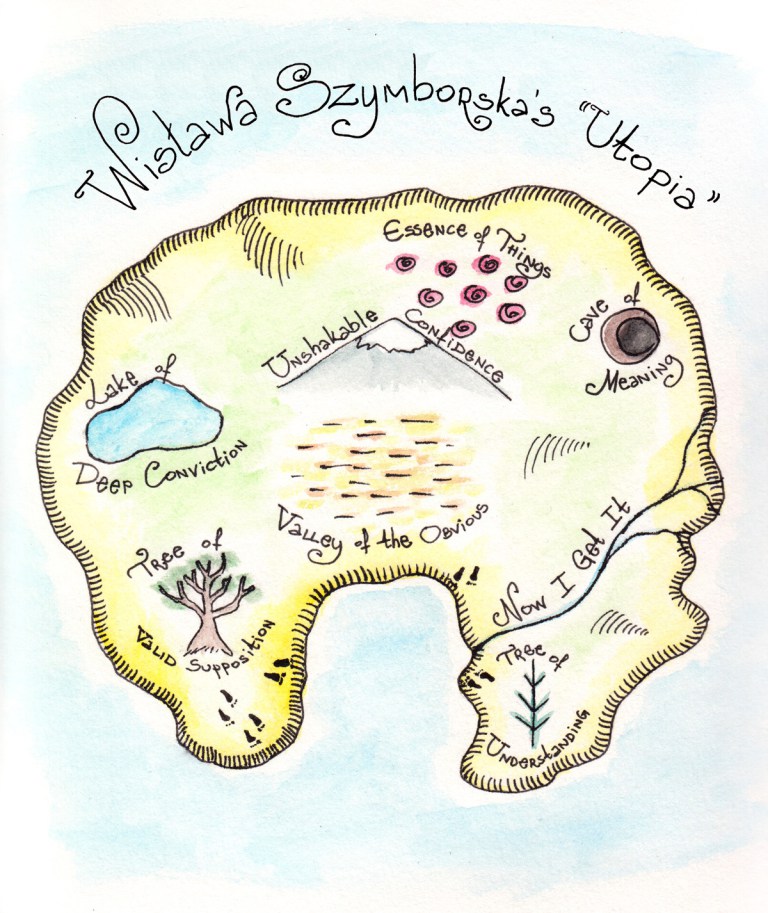

Utopia, Maria Popova

The truth, from Maria Popova in Brain Pickings:

“Attempt what is not certain. Certainty may or may not come later. It may then be a valuable delusion,” the great painter Richard Diebenkorn counseled in his ten rules for beginning creative projects. “One doesn’t arrive — in words or in art — by necessarily knowing where one is going,” the artist Ann Hamilton wrote a generation later in her magnificent meditation on the generative power of not-knowing. “In every work of art something appears that does not previously exist, and so, by default, you work from what you know to what you don’t know.”

What is true of art is even truer of life, for a human life is the greatest work of art there is. (In my own life, looking back on my ten most important learnings from the first ten years of Brain Pickings, I placed the practice of the small, mighty phrase “I don’t know” at the very top.) But to live with the untrammeled openendedness of such fertile not-knowing is no easy task in a world where certitudes are hoarded as the bargaining chips for status and achievement — a world bedeviled, as Rebecca Solnit memorably put it, by “a desire to make certain what is uncertain, to know what is unknowable, to turn the flight across the sky into the roast upon the plate.” —Brain Pickings

April 3rd, 2017 by dave dorsey

While spending a few weeks in Florida this month—helping my parents with some condo-related chores they can’t do themselves now—and getting in some morning runs on the beach, I’ve set up a little provisional studio to keep working on a current painting. (Running at low tide on the hard wet sand is the perfect surface; it gives underfoot just slightly, like an old wrestling mat.) I’d shipped the painting down, along with all the supplies I needed ahead of time, but my labors here kept me away from it for a couple weeks. It’s a little harder to spend a few spare hours on a canvas after half a day of cleaning out a garage when you have the equivalent of a mild, sunny summer day beckoning to you from the open garage door. With mockingbirds singing, ospreys building nests, jatropha in bloom, and a continuous cool breeze moving through the place from the Gulf of Mexico, it’s not as easy as it is in Western New York to keep your eyes aimed at a canvas. I even spent one afternoon at Myakka River State park checking out alligators sunning themselves on the river bank. So many ways not to work, so little time. I even spent two days driving the seven hours to Key West and back, with a full day and night in the southernmost key, stopping in Key Largo on the return to snorkel in the Atlantic coral reef.

What I found during all this time away from a canvas is that it can begin to look less and less inviting, the further in time you get from your last brushstroke. Every glance makes you wonder how much time it will take to actually complete the area you’ve started, and doubts creep in about either your ability or your enthusiasm. The charm begins to wear thin. The mojo wanes. Yet—and this is what I’ve encountered over and over, and it still comes as a slight surprise—as soon as you pick up a brush and put paint to canvas, everything snaps back into focus, the painting stirs fully awake as you break the spell. It’s as if no time has passed and the momentum returns immediately—four hours go by and you have to force yourself to put down the brush to eat.

There’s some sort of axiom in nature and in human enterprise: something is either growing or its dying. It can’t be put on hold. The longer I stay away from the work, the more it shrinks into the emotional distance and exerts less and less pressure on my attention and drive. In a sense, I can put it on pause, and it will stay as it is for as long as I stay away from it. Yet I have less and less of an impulse to return–so in a sense, it’s dying to me. What Poe called the imp of the perverse eventually takes hold: the paradoxical urge not to even look at the half-finished work when the way is open and time available to return to it. I’m drawn into a fallow period, the inertia of not painting. Yet one touch and it all comes back—because at that point, again, it’s growing into what it will become and that forward progress pulls me right back into a satisfying engagement with the work. My heart is right back in it. And the painting is as alive as it ever was. Between that stagnation and revival falls the shadow, as T.S. Eliot would have put it. I wonder how many paintings I’ve lost sight of in that shadow, without realizing all I needed to do was one step back into the light by picking up a brush.

April 1st, 2017 by dave dorsey

“In those days my world was no bigger than a couple of blocks. Huge worlds are in those two blocks. All I wanted to do was paint. It was like I couldn’t control it . . . I had tremendous freedom, my own little place that really would be such a world.” —David Lynch: The Art Life

March 30th, 2017 by dave dorsey

March 16th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Still Life with Golden Raspberries, oil on linen, on view in “PLACE” at Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati. I was very pleased to be invited to show at Manifest again this year. All of the shows there right now look excellent. Photos courtesy Jason Franz at Manifest.

Still Life with Golden Raspberries, oil on linen, on view in “PLACE” at Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati. I was very pleased to be invited to show at Manifest again this year. All of the shows there right now look excellent. Photos courtesy Jason Franz at Manifest.

March 14th, 2017 by dave dorsey

March 2nd, 2017 by dave dorsey

Libica, Elise Ansel, oil on linen

During my tour of the L.A. Art Show in January, a glimpse of Elise Ansel’s work from a distance reeled me into the Ellsworth booth about as quickly and effectively as anything I spotted in my tour of the entire fair. It was a small study based on a Poussin painting, reducing the original image to an abstract expressionist composition full of perfectly harmonized, intensely saturated tones with areas that looked as if the paint went straight from tube to canvas. If I had seen Ansel’s work before, and I may have, in a more absent frame of mind, it didn’t draw me in. This time, as I stood before that little study, I felt about as pleased as if I’d just stumbled upon the largest chocolate egg in a hunt on Easter morning. (Most of the work in the fair was a lot less stunning, therefore exceptional work tended to stand out even more powerfully than it would have done in a curated show. I had the same reaction to Kim Cogan’s small paintings a few booths away.) Barry Ellsworth, the gallerist, was staffing his own booth and told me a little about Ansel when I asked who’d done the painting, and he mentioned that she was also represented by Danese/Corey where, about a week ago, I discovered that Ansel has a new solo show. For anyone interested in seeing her work first-hand, the work will be on view in Chelsea for another ten days and includes some paintings even more remarkable than what I saw in California.

Ansel’s images are compelling for two reasons. First is the luxuriance of her rich, intense color, creating harmonies that feel both inevitable, yet freshly unpredictable, and sensuously felt. Her color is both inviting and beautiful. Matisse would have enjoyed these paintings, though it was Picasso who was more inclined to rework the occasional Old Master in his own idiom. She reprises images from Rubens or Veronese or Michelangelo, taking the original painting as an occasion to build a spontaneous, rapid translation of the historical painting’s colors into a contemporary calligraphic abstraction, freeing the colors of the original to overwhelm the original artist’s intent and completely define the new image. What she retains, though, is the original painting’s spiritual energy submerged into the libidinous pleasure of her color—the lyrics of the source are gone, as it were, and only the melody remains.

Second, she works essentially as an abstract expressionist, building flat patterns of various tones, and yet she’s able to convey a sense of great volume and space, a depth of field that has nothing MORE

February 27th, 2017 by dave dorsey

This is a ceramic representation of the earth as originally imagined in an Iroquois creation myth of the “world on a turtle’s back.” In the original myth the world rests on the back of a giant turtle, the American Indian equivalent of the Medieval notion of a firmament. In Barron Naegel’s reworking of the myth, the turtle and the planet are fused into one orb, the shell forming the bedrock below the life on the surface. Which happens to be, more or less, close to the way we view the planet ourselves. In Naegel’s small solo show at Keuka College you can see his latest figure drawings and his reinterpretation of the Iroquois myth in raku pottery. The drawings are masterful and traditional, studies from models at Steve Carpenter’s studio, and bring to mind the Renaissance and the Grand Central Atelier, though in them he’s trying to find a middle ground between representation and abstraction. One in particular, a cluster of figures woven together into a braid of limbs, brought to mind Nude Descending a Staircase. His raku planet is the show’s stand-out, and it was literally a trial by fire, a spontaneous process of discovering color experimentally through chemistry and heat–turning him into a bit of an alchemist. Here is how Barron described the process of getting the orb to its finished state through “re-oxidation”:

This is a ceramic representation of the earth as originally imagined in an Iroquois creation myth of the “world on a turtle’s back.” In the original myth the world rests on the back of a giant turtle, the American Indian equivalent of the Medieval notion of a firmament. In Barron Naegel’s reworking of the myth, the turtle and the planet are fused into one orb, the shell forming the bedrock below the life on the surface. Which happens to be, more or less, close to the way we view the planet ourselves. In Naegel’s small solo show at Keuka College you can see his latest figure drawings and his reinterpretation of the Iroquois myth in raku pottery. The drawings are masterful and traditional, studies from models at Steve Carpenter’s studio, and bring to mind the Renaissance and the Grand Central Atelier, though in them he’s trying to find a middle ground between representation and abstraction. One in particular, a cluster of figures woven together into a braid of limbs, brought to mind Nude Descending a Staircase. His raku planet is the show’s stand-out, and it was literally a trial by fire, a spontaneous process of discovering color experimentally through chemistry and heat–turning him into a bit of an alchemist. Here is how Barron described the process of getting the orb to its finished state through “re-oxidation”:

Raku can be a scary process, to say the least. I usually use tongs to remove the work. However I had to use an alternative approach, which in this case was to just grab it. I had all this  apprehension about heat, so I used firemen gloves blanketed with phone books completely saturated in water. First of all, I don’t have a Raku kiln which makes this process a lot, lot easier. So I basically have to lean over into the heat. The object itself is molten and it’s about as heavy as a bowling ball, but one with oil all over it, because of the molten glass. A slippery bowling ball at 1900 degrees! The process of Raku is based on reduction: it’s all chemistry. I’m stripping away the oxygen from the

apprehension about heat, so I used firemen gloves blanketed with phone books completely saturated in water. First of all, I don’t have a Raku kiln which makes this process a lot, lot easier. So I basically have to lean over into the heat. The object itself is molten and it’s about as heavy as a bowling ball, but one with oil all over it, because of the molten glass. A slippery bowling ball at 1900 degrees! The process of Raku is based on reduction: it’s all chemistry. I’m stripping away the oxygen from the glaze and introducing more carbon, which changes the metal colorants. How did I get it to where I wanted it? The blue and green you see on the surface are the result of re-oxidation. The first time I fired it, it came out red, looking more like Mars! I reheated it to about 800 degrees a baseline temperature, and then with a welding torch reworked areas to get certain colors. I had to try three times to get it to work out.

glaze and introducing more carbon, which changes the metal colorants. How did I get it to where I wanted it? The blue and green you see on the surface are the result of re-oxidation. The first time I fired it, it came out red, looking more like Mars! I reheated it to about 800 degrees a baseline temperature, and then with a welding torch reworked areas to get certain colors. I had to try three times to get it to work out.

Using firemen’s gloves and wet phone books as a buffer between the gloves and the pottery, which would have stuck to the molten glass, he was able to retrieve his globe from the fire. It’s an unpretentious technique also used at the Corning Glass Works for handling molten forms only an hour’s drive away. It struck me that with his ceramic planet, Naegel was replacing oxygen with carbon in the surface to get the color he wanted, much as we’re doing (sort of) to the actual planet, but in his case, it had exactly the desired effect: turning a dull red sphere into this emerald world.

February 20th, 2017 by dave dorsey

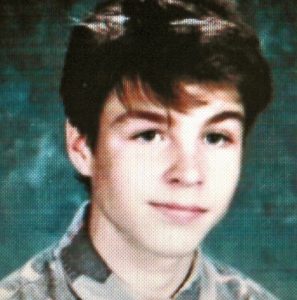

Ryan Adams, a while ago

You get the sense from some creative work, Proust’s maybe more than anyone who ever lived, that the author of the work considered everything in some sense magically interesting or valuable–and this is where language offers no adjective for what a work of art actually conveys, the isness of things. It isn’t that what’s being represented is valuable, or marvelous, or (pick any other available adjective.) It’s something else. What you sense from looking at a Van Gogh or reading Swann’s Way is how the individual who created the work had what the fellow I’m going to quote below called a total appreciation for life just as it is-with nothing left out, including the crime and the evil and the horrible suffering and injustice. Bruegel has this quality–there’s nothing that isn’t worthy of being painted, and when he paints it, it’s suddenly (again, try to imagine that non-existent adjective or noun). There’s no word for what’s going on in that transformation or disclosure that happens in art. Language has no verb for the work being done by the painting or the novel. Celebrate, affirm, savor, appreciate, cherish–sorry, no. Below are seemingly extemporaneous observations that attempt to express (bumping intentionally up against the limits of language and showing how words fail to capture what’s going on) the urge to create something that will condense life itself into some created thing, or (what amounts to the same thing) alchemically make something inanimate appear to come alive. In a way, the urge to create is something like the will to be so aware of everything that you yourself are fully alive. These are remarks from the singer Ryan Adams, talking with Bob Boilen in the most recent episode of NPR’s All Songs Considered. It gets close to showing how impossible it is to say what’s really happening in great creative work, in any medium:

You manifest a meaning from a thing to yourself, in whatever format, a painting, a poem, a song, an article, or a novel or a note to a friend or a drunken text or email or spray painting on brick walls or inappropriately decaling your car. You conjure this feeling. There’s this thing inside of human beings, this total appreciation of being alive. It’s so profoundly in our gut. Even all of these people who would seemingly be horrible people, somewhere in there there’s this longing, this reaching up, and in the right way if it’s channeled, there’s some kind of a notion in them of “I have to document this thing that I saw” that becomes these songs, or these poems. We’re all in the high school of life and waiting for the teacher to turn around so we can take that pen we’ve been chewing on long enough that it’s got a sharp enough end that you could scratch your initials into that ventilator in gray/blue paint over by the window. It’s the same thing as those beautiful drawings in caves, where you see pictures of horses and wild game they were hunting. That person that day was either thinking of how beautiful those animals were or how it felt to be out there with them that day.

February 17th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Sweet Kate, In for Repairs, Ray Hassard, oil on canvas

I came away from the current show at Oxford Gallery craving more excellent oils from Ray Hassard. His pastels are masterful and the latest work he’s been doing in Florida may be better than anything he’s done in the past: the way he captures the light so that it gives a sense of depth and even immense volume to the space in these small landscapes is remarkable. Yet, maybe because I’m an oil painter, my favorites are the oils in the current Oxford show. Like a number of other Oxford artists—Chris Baker and Matt Klos—he’s fascinated by the most commonplace scenes. Beyond the immediate pleasure offered by the color and the play of light and shadow, he conveys a sense of completion and harmony in scenes that invites you to look again, in a fresh way, as if for the first time at scenes you otherwise might not even notice. Hassard picks the least auspicious subjects: a leftover holiday decoration on New Year’s Day, a crossing guard brandishing a stop sign, or someone nearly lost in shadow cleaning and repairing an old boat in storage. My favorite painting of Hassard’s was in a previous show at Oxford, a small image of a parked pickup truck, a view one could enjoy of thousands of trucks parked in small towns and villages anywhere in dozens of states—and you would never give any of them a second look if you passed them on the way to somewhere else. The light, the color, and the abbreviated rendering with assured brushwork—he could have done the painting in a single sitting, en plein air—concentrate energy and a sense of ease in Hassard’s execution. Bill Santelli and Bill Stephens joined me at Oxford to see the new work and Santelli pointed out how Hassard again and again composes an image, like Diebenkorn, so that smaller areas of comparatively intense activity are clustered close to a top edge, with a more uniform expanse of color beneath it—a field, a floor—creating a tension between the complexity of form against an open void below it. Hassard’s real subject is the unity and uniformity of the light, rather than anything it reveals in particular. My favorite in this show is Sweet Kate, In For Repairs, his view of an old boat maybe being readied for another launch. It’s actually one of his least colorful, a field of neutral tones with a few small notes of muted orange, blue, green and a tiny stripe of red. In the foreground: a trash barrel with a loose load of scrap jutting out in all directions like a month-old bouquet, and a narrow, tall pylon. All the activity he depicts, the subject of the work, is just visible, pushed to the background, half-hidden in shadow. The worker, up on a ladder, is barely indicated, perfectly done, with a few patches of color, tucked away, almost out of view, like an Easter egg. The light is modulated gently throughout the entire scene, and even the higher reaches of the repair shop are dark but still dimly illuminated, with the darkest shadow reserved for small pockets of space under the boat. You feel the day, the season, a world in which the boat repair is neither more nor less interesting than the trash in the barrel—it’s all good and essential to the whole.

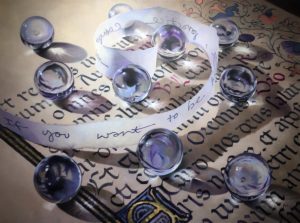

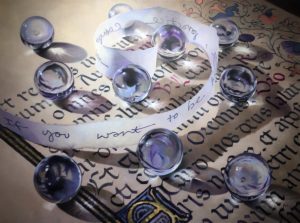

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.

Still Life with Golden Raspberries, oil on linen, on view in “PLACE” at Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati. I was very pleased to be invited to show at Manifest again this year. All of the shows there right now look excellent. Photos courtesy Jason Franz at Manifest.

Still Life with Golden Raspberries, oil on linen, on view in “PLACE” at Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati. I was very pleased to be invited to show at Manifest again this year. All of the shows there right now look excellent. Photos courtesy Jason Franz at Manifest.

This is a ceramic representation of the earth as originally imagined in an Iroquois creation myth of the “world on a turtle’s back.” In the original myth the world rests on the back of a giant turtle, the American Indian equivalent of the Medieval notion of a firmament. In Barron Naegel’s reworking of the myth, the turtle and the planet are fused into one orb, the shell forming the bedrock below the life on the surface. Which happens to be, more or less, close to the way we view the planet ourselves. In Naegel’s small solo show at Keuka College you can see his latest figure drawings and his reinterpretation of the Iroquois myth in raku pottery. The drawings are masterful and traditional, studies from models at Steve Carpenter’s studio, and bring to mind the Renaissance and the Grand Central Atelier, though in them he’s trying to find a middle ground between representation and abstraction. One in particular, a cluster of figures woven together into a braid of limbs, brought to mind Nude Descending a Staircase. His raku planet is the show’s stand-out, and it was literally a trial by fire, a spontaneous process of discovering color experimentally through chemistry and heat–turning him into a bit of an alchemist. Here is how Barron described the process of getting the orb to its finished state through “re-oxidation”:

This is a ceramic representation of the earth as originally imagined in an Iroquois creation myth of the “world on a turtle’s back.” In the original myth the world rests on the back of a giant turtle, the American Indian equivalent of the Medieval notion of a firmament. In Barron Naegel’s reworking of the myth, the turtle and the planet are fused into one orb, the shell forming the bedrock below the life on the surface. Which happens to be, more or less, close to the way we view the planet ourselves. In Naegel’s small solo show at Keuka College you can see his latest figure drawings and his reinterpretation of the Iroquois myth in raku pottery. The drawings are masterful and traditional, studies from models at Steve Carpenter’s studio, and bring to mind the Renaissance and the Grand Central Atelier, though in them he’s trying to find a middle ground between representation and abstraction. One in particular, a cluster of figures woven together into a braid of limbs, brought to mind Nude Descending a Staircase. His raku planet is the show’s stand-out, and it was literally a trial by fire, a spontaneous process of discovering color experimentally through chemistry and heat–turning him into a bit of an alchemist. Here is how Barron described the process of getting the orb to its finished state through “re-oxidation”: apprehension about heat, so I used firemen gloves blanketed with phone books completely saturated in water. First of all, I don’t have a Raku kiln which makes this process a lot, lot easier. So I basically have to lean over into the heat. The object itself is molten and it’s about as heavy as a bowling ball, but one with oil all over it, because of the molten glass. A slippery bowling ball at 1900 degrees! The process of Raku is based on reduction: it’s all chemistry. I’m stripping away the oxygen from the

apprehension about heat, so I used firemen gloves blanketed with phone books completely saturated in water. First of all, I don’t have a Raku kiln which makes this process a lot, lot easier. So I basically have to lean over into the heat. The object itself is molten and it’s about as heavy as a bowling ball, but one with oil all over it, because of the molten glass. A slippery bowling ball at 1900 degrees! The process of Raku is based on reduction: it’s all chemistry. I’m stripping away the oxygen from the glaze and introducing more carbon, which changes the metal colorants. How did I get it to where I wanted it? The blue and green you see on the surface are the result of re-oxidation. The first time I fired it, it came out red, looking more like Mars! I reheated it to about 800 degrees a baseline temperature, and then with a welding torch reworked areas to get certain colors. I had to try three times to get it to work out.

glaze and introducing more carbon, which changes the metal colorants. How did I get it to where I wanted it? The blue and green you see on the surface are the result of re-oxidation. The first time I fired it, it came out red, looking more like Mars! I reheated it to about 800 degrees a baseline temperature, and then with a welding torch reworked areas to get certain colors. I had to try three times to get it to work out.

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.

In reproductions, it’s hard to recognize how masterful Barbara Fox’s work is in reproduction. Her images of scattered glass balls resting randomly on illuminated manuscripts are stunning, not only in how perfectly she captures the behavior of light, but also in her handling of oil. There’s a double-entendre in that word “illuminated” in her work: the calligraphy itself suggests pages from the Book of Hours, but these pages are, as well, illuminated by an angle of light she returns to again and again, falling across the page, and through the orbs, from the upper edge—from above, given the viewer’s frame of reference. So these are illuminations of illuminations, and what at first seems puzzling and restrained, the way in which Fox paints almost the same image again and again, begins to feel like a disciplined, repetitive meditation. When you stand close to one of these paintings, the way Fox applies oil confirms and strengthens the sense of perfection she achieves—from a few feet away you have the sense that her script and orbs are as crisply defined as a hard-edged abstract, but up close there is a feathery quality to her lines and edges from the way her paint rides the fabric’s texture. That painterly quality is part of what makes the image glow. In one of the most impressive paintings, the largest canvas, A Sense of Possibility, a translucent ribbon falls across the page on which someone has written words that take a while to decipher—you see them from the front and the back, so without a mirror handy, you have to create a reverse image of the cursive writing in your head. Bill and I finally cracked the code even though we had to guess the two key words, given the angle of the ribbon: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Happy and compassion are almost missing, but enough of the second word is visible. The words of the manuscripts beneath her orbs hide their meaning, unless you’re fluent in Latin, but even this wisdom, revealing and yet withholding itself simply by holding its curve, makes you work to understand it. As all wisdom does. Once you do, it feels almost like a commentary on all of Fox’s work: it’s a practice to achieve a stillness that serves as the home for that compassion, and the happiness that flows from it.