Archive Page 33

New Burnes

A new, very assured portrait from Sarah Burnes, in Oregon. Love how, as usual, she keeps the values bright, narrowing the range of light/dark, as well as restricting her palette to a very limited number of muted colors, with all that feeling concentrated in the slightly pinker tones around the mouth, one fingertip and an elbow. And her previous painting in the background feels completely integrated into the scene, as if the model is dreaming or remembering on earlier moment in that chair.

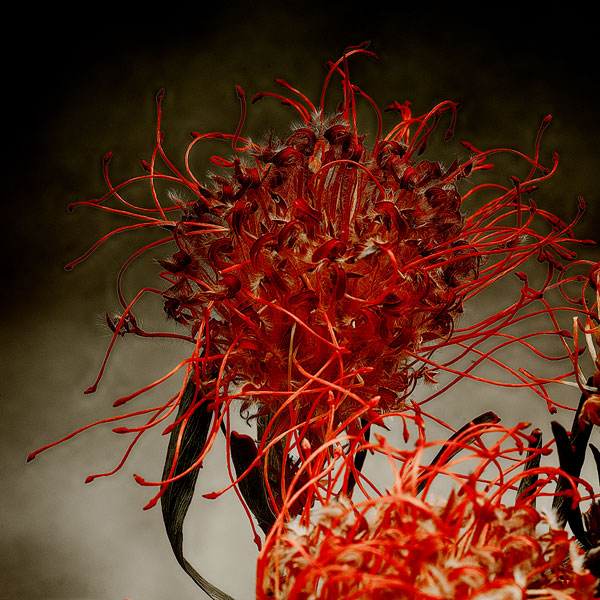

Remembrances

I’m eager to see Alan Gaynor’s solo show at Viridian Artists, starting this week: his shift toward the organic forms of these wilting flowers struck me as different from all of his previous work when I first saw them. All of his work is personal, but there’s a depth of feeling and vulnerability in the new work that’s arresting. His earlier shots of architecture reflected the passion he’s invested in four decades as a successful New York architect, yet the flowers are a shift toward something more intimate and unruly. He started taking this series while his wife was dying, and the gravity of his inspiration comes through in the beauty he finds in what are essentially leftover decorations, ready to be tossed out. His opening reception is tonight at Viridian. I talked to him a few days ago about his work:

Alan Gaynor: When I was in architecture school I took a photography course because I thought I didn’t know how to photograph, and I thought I should at least be able to take vacation pictures. I studied with a woman who gave us an assignment to take a roll of film, back in the day of wet developing. We’d shoot it and develop it on our own and come in with contact sheets. I did two rolls because I’m an overachiever. This was in 1969 maybe. I came back with my contact sheets and she looked at me in front of fifteen people in the class. She said Oh my God, do you know Eugene Atget’s work? I said, “I have no idea.” She said, “You should look it up. These are wonderful.” That was the beginning. I photographed all through college. I graduated from 35 mm to 4 x 5 and I shot 4 x 5 black-and-white film for years. I put it down since starting and growing this business was a double-time job. About twenty years ago I picked up the camera again and again started shooting black-and-white because I didn’t know how to process or print color. It was too difficult for me. I set up a dark room and started taking courses with people like John Sexton who was an apprentice to Ansel Adams for a long while. With some people who were very large names and from every one of those people I learned something. I started shooting buildings and cityscapes. Then I got interested. My son is seventeen and he was a subway freak since he was four years old. He had a real wanderlust as a child. I began to appreciate the subways in a way I hadn’t before. I stopped and started looking at them. I had to get a pass from the MTA and set my camera up, but I still got my chops broken by the police but that was OK. They’d let me finish the shot and that’s all I cared about. I had a pass but you don’t want to argue with them. I’d beg them to let me finish the shot. I shot some landscapes for a while. I switched to digital.

DD: That would make color possible.

AG: It made color easy but black-and-white difficult until I learned to convert to black-and-white. I love Indian architecture, Islamic architecture. I started doing these panoramas from mid-level up in buildings. Those were taken knowing exactly how they were printed. A city you experience as a layering of buildings not individual architecture. The layering of one thing on top of another on top of another on top of another. Those panoramas were designed to express that. Then during this period my wife got very, very ill.

DD: I think that’s a big factor in what’s going on now in your work.

AG: It’s a very big factor. The first flower shot I took were tulips I bought for her. They were her favorite flower. As they were dying, she was dying. After that I started photographing half-dead or three-quarter-dead flowers sort of as a tribute to her but also to work it out as a photographer.

DD: Those are fascinating. The first of your work I saw were the panoramas that seemed very controlled, not that these aren’t controlled, but they’re opposite in the quality of line, the color . . . it’s all controlled in the way you frame it. You’re setting it up no matter what you shoot.

AG: The thing about photography, it’s all about framing. I take very few photographs. It’s extremely deliberate. The camera is something I use to compose; it’s not random. It’s why I don’t do street photography. I don’t do people. I look at someone like Walker Evans who did both that and the sort of things I do. He did lots of different things. I’m only interested in the composed; not the accidental or photographing people doing wonderful things or funny things. Not that I don’t like people, it isn’t what I’m interested in photographically.

DD: Gary Winogrand, for example.

AG: He’s a very fine photographer. But it isn’t random. Everything informs what you do. My being an architect informs what I do even when I’m photographing flowers.

DD: With the flowers, the whole situation with your wife is there in those pictures and other people wouldn’t take them that way.

AG: They wouldn’t see the beauty in dying flowers. I don’t know who else shoots dying flowers; not that I was looking to do something nobody else was doing. Part of the democratization that the camera gives is that anybody can click a button but not everyone can see or compose; not everyone sees the shot in front of them. It isn’t a matter of putting the camera on automatic and walking down the street.

DD: Describe for me how you do the flowers.

AG: It’s very simple. I wait until the flowers get to a particular state and then use a relatively diffuse overhead light only. I shoot against a seamless gray background most of the time. I started out using a Canon 5D Mark II graduated to a Hasselblad with a macro lens. It’s a lovely piece of machinery. I have an Arca Swiss view camera with a digital back. My camera of choice is the Hasselblad. I have an older one that will take a 39 megapixel back with a proper mount. Hasselblad lenses are wonderful. It’s certainly not a consumer camera. When I shoot architecture with my Canon I go nuts trying to correct the distortions. The lens distortion. Canon lenses are wonderful but it’s not a Hasselblad lens or a Leica lens.

DD: You get curving lines?

AG: Yes. Barrel distortion. The Haselblad lens is much higher quality. The panoramas are done on a 6 x 9 view camera with Rodenstock or Schneider view camera lenses, with a sliding back that allows me to stitch together three or four shots. Those are wonderful lenses. If I set the view camera right I don’t get distortion. It’s a lot of the work, and it has taken me years to learn. There is a lot of work I couldn’t do. If you took me to a photo studio, I would not be able to shoot products.

DD: That has a lot to do with lighting.

AG: Yes, and I use very rudimentary lighting.

DD: Are you reflecting off a white surface?

AG: No, it’s direct light. It’s being filtered through a shade-like material. I shoot on my dining room table, frankly.

DD: Do you use a full spectrum bulb?

AG: No. In Photoshop the gray is gray, or some other color I want. A lot of it is post-production.

DD: You have to get depth of field right though.

AG: You can do focus stacking. With RAW files, it allows you—I haven’t done it yet—but it allows you to stack focus. You shoot ten RAW files, each one is focused at a different depth.

DD: Like HDR, for exposure.

AG: Yes. A lot of what I do is post-production.

DD: When you pick these flowers, are you picking them specifically for the photographs?

AG: I have a friend who works for a commercial florist and I pick up her dead flowers. After an event, I get the flowers.

DD: That goes with the whole feel of what you’re doing with the shots. They’re almost like found objects.

AG: Either I take them or they go into the trash, or the compost if we’re being ecologically responsible. I feel like I’m getting to the end of the flowers, but I don’t know. I’m so involved in the architectural business, with the move to the new location, I’m not sure.

DD: How long has your firm been around?

AG: This is our fortieth year. In ’75 I decided I needed to be in Manhattan. I was in Brooklyn at the time. For $85 a month I had a full floor of a brownstone.

DD: That’s amazing.

Costs, rewards, deliberations

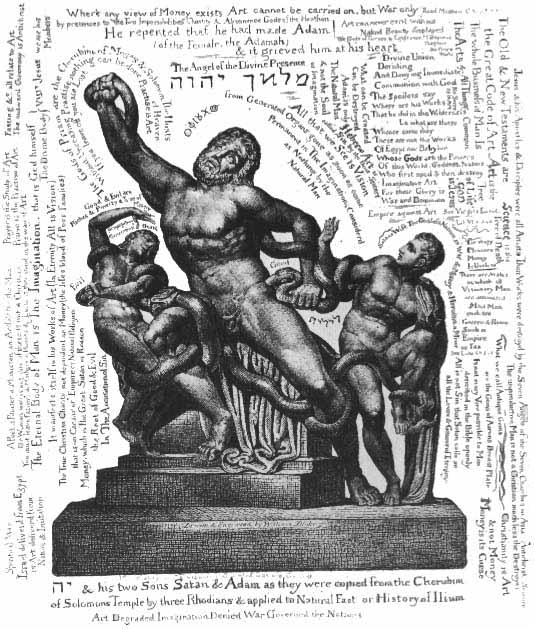

“Where any view of Money exists Art cannot be carried on . . .”

–William Blake’s annotations to the Laocoon

I grew up in a world in which what artists aspired to was to be able to go to their studio, make art, sell a work occasionally, so they can buy some Wheaties, and some records, and listen to records, and make art, and eat Wheaties. And that was their goal: stay away from the straight world, and stay away from the university, and live their lives.

When I was invited to apply for membership at Viridian Artists in 2011, I didn’t first take my samples around to regular commercial galleries in New York City to see if any would represent me for no charge other than, well, half the revenue of anything they sold. Fifty percent commissions didn’t bother me. That’s standard. A gallery has to eat too. At the time, I didn’t think I had the track record to have, say, a Hirschl & Adler take me on—wishful thinking even now, no doubt—yet I still deliberated a while before committing myself to $7,500 for two and a half years of participation and a solo show. (That $7,500 is only the beginning, as I’ll describe shortly.) Once I joined, my first task was to help the gallery move from its old space on W. 25th St. to its current spot on W. 28th because it was already in need of a less expensive venue for its members—as real estate continues to get pricier in New York City. By “help the gallery move” I mean I carried a lot of stuff down several floors and crammed it into the bed of Rush Whitacre’s pickup, at which point we drove it a few blocks north and unloaded it. Putting in the labor was part of the deal. Members agree to work at the gallery for many hours every year, which is a way of supporting it, but also, for those of us who live hundreds of miles away, another additional cost and benefit. The cost you measure in dollars: gas, lodging, parking, beer, Philly cheesesteaks, Thruway tolls, rides through the Lincoln Tunnel, subway fare, and admission to museums. (Some of that isn’t really a requirement of membership but an unavoidable consequence of coming down for a visit.) The benefits of hanging around Manhattan are less tangible, but just as real, and I will get to those down below.

Now, three years later, I face the choice of renewing my full membership MORE

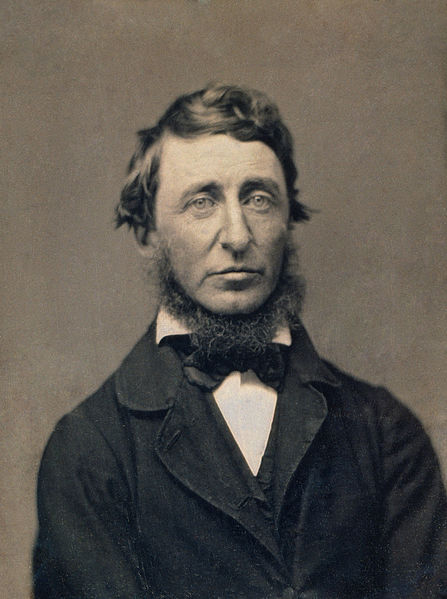

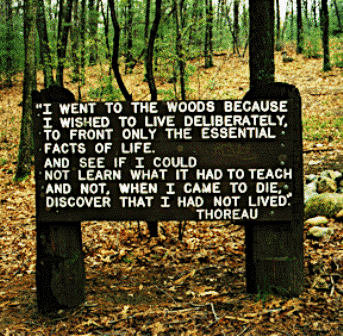

More of Henry and me

After a couple years in the working world, when I decided to return to college and enter graduate school to study literature in the 70s, I read Walden. It has always struck me as an essential book for anyone attempting to leave behind commonplace assumptions—the sort of wisdom that advises you to focus on earning money, gaining power, being well-known, contributing to society, and so on—and simply spend a couple years doing nothing but being aware of life. (Of course, if you get married and have children, all the commonplace wisdom kicks into gear, which is what happened to me.) Granted, Thoreau found a more direct way to “be aware of life” than by studying what people had written about life, yet Walden is full of quotes, so I imagine his two years spent doing what most people would consider nothing was occupied with a fair amount of reading. Hence, Walden is a reasonable book to read before driving to Illinois to study Melville, instead. (I was still thinking fondly of you, though, Henry.)

After a couple years in the working world, when I decided to return to college and enter graduate school to study literature in the 70s, I read Walden. It has always struck me as an essential book for anyone attempting to leave behind commonplace assumptions—the sort of wisdom that advises you to focus on earning money, gaining power, being well-known, contributing to society, and so on—and simply spend a couple years doing nothing but being aware of life. (Of course, if you get married and have children, all the commonplace wisdom kicks into gear, which is what happened to me.) Granted, Thoreau found a more direct way to “be aware of life” than by studying what people had written about life, yet Walden is full of quotes, so I imagine his two years spent doing what most people would consider nothing was occupied with a fair amount of reading. Hence, Walden is a reasonable book to read before driving to Illinois to study Melville, instead. (I was still thinking fondly of you, though, Henry.)

I’ve always been pleased by the fact that, early on, Thoreau shared his budget with his reader. It wasn’t really a budget, but closer to the equivalent of a receipt from Home Depot, detailing how much he spent on the little house (a room more than a house) he built for himself at the edge of the pond. I don’t know how much, in current terms, a dollar was worth in 1850, back before the Civil War began, but inflation aside, his investment sounds pretty reasonable:

Boards, ………………………… $8.03½, mostly shanty boards.

Refuse shingles for roof and sides, 4.00

Laths, ………………………….. 1.25

Two second-hand windows with glass, … 2.43

One thousand old bricks, …………… 4.00

Two casks of lime, ……………….. 2.40 That was high.

Hair, …………………………… 0.31 More than I needed.

Mantle-tree iron, ………………… 0.15

Nails, ………………………….. 3.90

Hinges and screws, ……………….. 0.14

Latch, ………………………….. 0.10

Chalk, ………………………….. 0.01

Transportation, ………………….. 1.40 I carried a good part on my back.

In all, …………………… $28.12½

These are all the materials, excepting the timber, stones, and sand, which I claimed by squatter’s right. I have also a small woodshed adjoining, made chiefly of the stuff which was left after building the house.

I intend to build me a house which will surpass any on the main street in Concord in grandeur and luxury, as soon as it pleases me as much and will cost me no more than my present one.

A house for $28. I think you might have gotten a foreclosed underwater house at auction in Detroit for that in 2009, but I don’t think I could build even a Lego version of Henry David’s home on that budget now. I’m not sure it would pay for a movie for two, if you require popcorn. MORE

Is the price right?

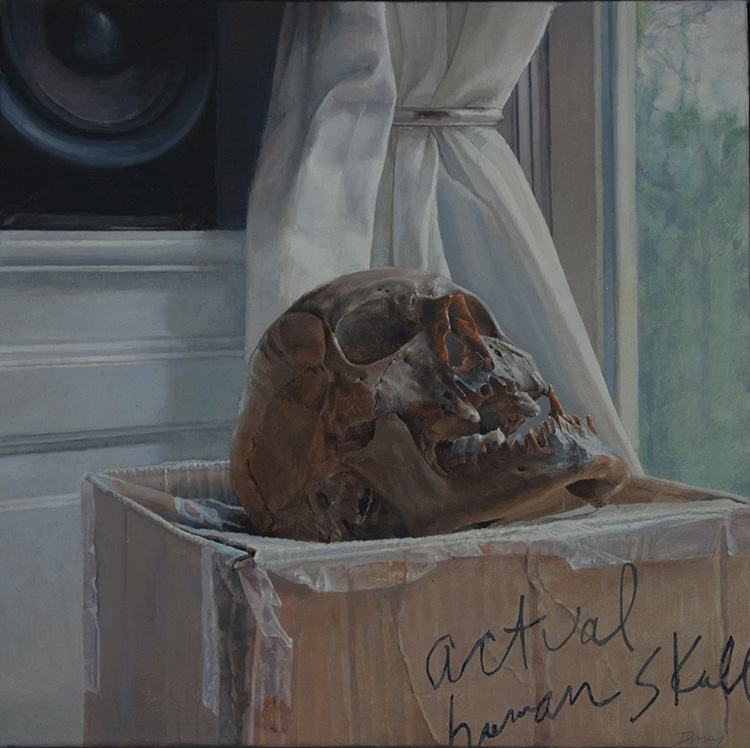

Painting is one way to live a meaningful, gratifying life, but it’s rarely a good way to make a living. Trust me, nothing bears this out better than my own pursuit of painting for the past few decades. Mostly, I’ve done it privately, without showing my work, as I went about the job of earning a living through my writing. For the past seven or eight years, I’ve started exhibiting my work, selling it, winning a few awards, and testing to see if I can’t find more of a market, and more recognition for what I do. As a result, I’ve sold paintings for thousands of dollars (though not lately), in itself a happy outcome, though never remotely enough to paint as a way of paying all my bills. I’ve been reviewed favorably several times. In my mailbox, I’ve found an unexpected check from a museum in Marin County as a reward for winning the top prize in a juried exhibition there–and I’ve been handed money a couple other times as a recognition of my work’s quality. I’ve been included in two of the Manifest international exhibitions in print, an honor valued by artists around the world who recognize in it a model for gaining exposure among those who don’t judge art by reputation or price. In short, I’ve been noted for the quality of my work, in under-the-radar ways, and people have wanted to own it enough to pay as much as $6,000 for one of my paintings. I consider these things encouragement along the way toward . . . well, this is one of the challenges of being an artist, simply knowing where you actually expect it to lead. (More thoughts on that challenge at a later date.) In my own case, if nothing else, I wish it could simply lead toward the ability to keep making art on a daily basis, art that other people want to look at or own or talk about, or simply to make art that would be the equivalent of working as an engineer in Soul of a New Machine, where a creative crew didn’t expect to get rich by developing a new computer, but wanted the equivalent of a winning pinball game that awarded them at least one more free game of pinball. In other words, to do something self-sustainingly creative. Which circles back to the subject of money in some form or another.

So, in other words, by various measures I’m modestly successful, yet not in a way that means that I have any particular standing as an artist where it is considered to count the most (I don’t myself accept this measure of quality): among the elite set who buy for museums, review for the major art publications, create a fast track for recent Ivy League art grads who ask more for their work than I suspect I ever will, though they have been making art for five or six years, and I’ve been painting seriously since the 70s. In other words, you can belong to a relatively small set of people who produce very good work and still be considered little more than a pilot fish swimming vigilantly around the fins of the sharks, trying to stay alive on what the apex predators don’t swallow from the larger currents of money that flow through galleries like Gagosian and Zwirner and wherever else the economically lucky few show and sell their work. (Some of that work is excellent, even though it’s ridiculously expensive.) None of this is necessarily unjust or wrong, but I sometimes wonder how many people realize that the vast majority of the art being produced in the world today is done quietly (discounting the occasional, uncalled-for noise of this blog) by people like me, who do it out of devotion rather than common sense, who don’t sustain ourselves by selling our work, and instead teach or drive cabs or staff a gallery or write for income—insert dozens of ways to make a living here—in order to paint or construct or script something during the half day we allocate for the making of art, often seven days a week, every week of the year. It’s easy enough to see our work, if you seek it out, but it seems to me that fewer and fewer people are seeking it out now, and the buying of art has become something mostly the richest people do at brief, migratory gatherings of those who can keep the price of anointed art in the hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars.

At the start of Walden, Henry David Thoreau offered what I consider the most intimate glimpse into his project of finding transcendence in nature: he shared his budget. He reduced his spiritual pursuit, his dream of a fleeting union with nature, down to the dollars and cents that actually kept it going. The man had a sense of humor, and he may have been a transcendentalist but he was as stubbornly realistic as they come. I don’t recall reading much commentary about this extremely Yankee gesture of toting up the pennies he had to earn and spend to aim for a higher state of consciousness. I consider the pursuit of art, at least the way I do it, as a way of walking along a path at least parallel to Thoreau’s: you hope, along the way, to get a glimpse of something greater than the daily grind, hidden within it, and, like all good things, it costs you something, in both economic and personal terms. If you’re an artist at my level, anyway. If you’re a Warhol or a Koons, it seems you just get paid to do whatever you decide to do when you get up in the morning. I and my peeps–you know who you are–aren’t familiar with this state of affairs.

Next up, when I’m able: the budget for a solo show when you bear the costs yourself. (As I’m doing for one in June.)

Weird works

You may not think I’m weird, and I may live in a suburb and tend a garden, but talk to people who know me, all right? I am. I really am! This Atlantic: article points out that this would be a good thing, in marketing terms, even though studied weirdness when it comes to the art world doesn’t appear to be in short supply:

Our brains associate eccentricity and creativity in musicians, painters, writers, and other artists—as long as weirdness doesn’t feel like a gimmick. Once we form a stereotype of the erratic artist, we may see those who fit the stereotype more snugly as being better artists.

However,

Even if you decide to scheme up a whole crazy artist persona, it’s likely that at least some people won’t see through the plot and will grant you greater regard. So don that outfit of veal or vomit—assuming you’re doing something edgy with your work. If, however, you’re hoping to make it big in still life, it’s probably better to keep the food on the table.

Oh.

It’s alive

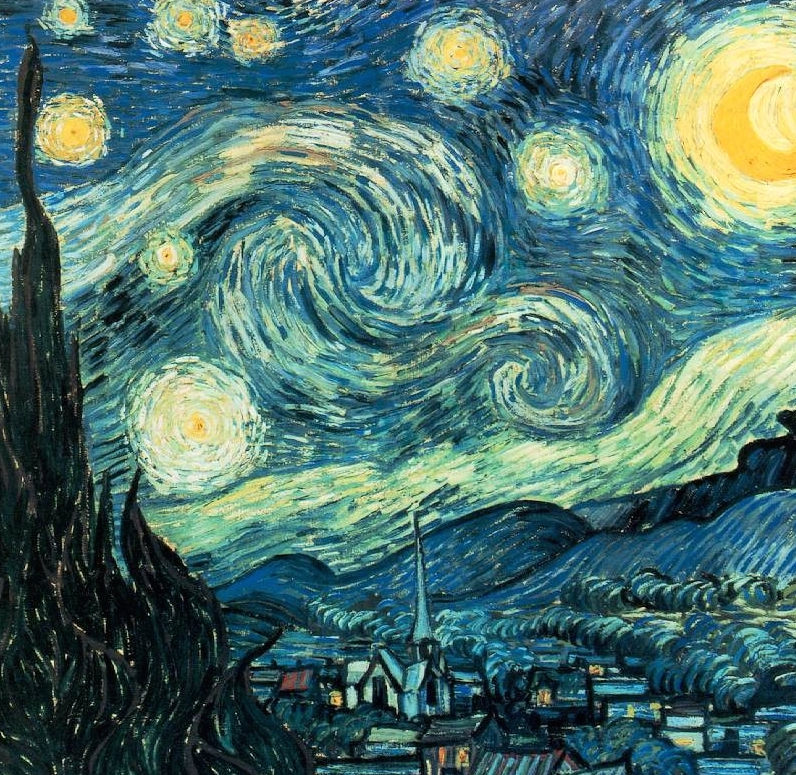

Visual art attempts to go places that words and thought can’t reach. I couldn’t help but think of Blake, Van Gogh and Burchfield–and the “everliving fire” of Heraclitus, for that matter–while reading this skeptical atheist scientist’s account in the New York Times of when the whole world seemed to be come alive around her. It was a harrowing experience that she now can’t find words to describe and was consistent with mystical experience described in most cultures. Her rediscovery of this experience many years later in her journal enabled her to reach “a truce with God”:

Visual art attempts to go places that words and thought can’t reach. I couldn’t help but think of Blake, Van Gogh and Burchfield–and the “everliving fire” of Heraclitus, for that matter–while reading this skeptical atheist scientist’s account in the New York Times of when the whole world seemed to be come alive around her. It was a harrowing experience that she now can’t find words to describe and was consistent with mystical experience described in most cultures. Her rediscovery of this experience many years later in her journal enabled her to reach “a truce with God”:

Fortunately, science itself has been changing. It was simply overwhelmed by the empirical evidence, starting with quantum mechanics and the realization that even the most austere vacuum is a happening place, bursting with possibility and giving birth to bits of something, even if they’re only fleeting particles of matter and antimatter. Without invoking anything supernatural, we may be ready to acknowledge that we are not, after all, alone in the universe . . . it could be that the universe is itself pulsing with a kind of life, and capable of bursting into something that looks to us momentarily like the flame.

Upcoming shows

My work will be featured in a number of shows this spring and summer. It was a bit of good news just in time to pick up my mood this morning that I’ll have a painting in the 29th Tallahassee International at Florida State University. I’m honored to be among some impressive company. I’d like to know more about Cynthia Mason’s work, for example. Here are some shows on schedule so far:

SOUTHWORKS, Oconee Cultural Arts Foundation, April 11 – May 9.

PROVERBS AND COMMONPLACES, Oxford Gallery, May 3-June 14.

POLARITIES, Still Lifes and Other Oppositions, solo exhibition, Viridian Artists, June 10-June 28. Reception: June 12, 6-8pm.

29th TALLAHASSEE INTERNATIONAL, Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts, Aug. 25 to Oct. 5.

INTERNATIONAL PAINTING ANNUAL 4 Exhibition in Print, Manifest.

I hope to get into a couple more, but if I don’t, I can’t promise that I’ll keep you informed about it.

Gallery mortality alert

Long directories of open galleries and the recent overview of the gallery scene in the New York Times to the contrary, your trusty sentinel will continue to conduct his ongoing gallery death watch. Many seem to believe lately that all we’ll have in the future are buyers with jet lag from art fair hopping or carpel tunnel from Web surfing, followed by the writing and mailing of checks. The Internet has been good to me, in that regard, now and then, and may bring buyers in the future, thanks primarily to Art Brokerage, but a solo show in a gallery is for me the equivalent, in music, of a great album, as opposed to a single. Where are the White Albums, the One Man Dogs, the Evil Empires of our day? Well, actually, some bands, like Spoon, do produce integrated sets of music on LP. Gimme Fiction, for example. Fox Confessor Bring the Flood, which is all of a piece, from Neko Case. The album as a coherent unit of creative effort survives. And great solo shows, like Susie MacMurray’s at Danese, are still happening. I’d hate to lose them. The best shows are greater than the sum of their parts. The museums we will have always with us, anyway, right? But the loss of galleries is just another loss of Main Street mom-and-pop commerce in favor of the big box warehouse. This article tries to finger the culprits, but it’s pretty much everything: our top-heavy ancien regime income distribution (that wouldn’t be a pejorative historical reference if the super rich woke up to what’s needed), the Internet, the art fair, and, I think, the way art has tended since, well, Manet, addressing itself to a more and more exclusive, insular audience. Art is itself part of the problem when it’s a cerebral, clever, recherche exercise addressed to a tiny coterie of initiates and forgets that mysterious beauty is Job One.

From the piece by Anthony Haden-Guest: “One truism is that the market now governs the art business as never before and that the market is subject to the 99/1 effect, as most markets seem to be these days. What I mean by this is that there is generally one percent of winners in a market and then there is everybody else.”

Sue McNally

Wonderful painting. Instantly recognizable as a “cover version “–in musical terms–of Burchfield’s painting, and yet it stands on its own perfectly, and is clearly the work of this artist, Sue McNally. A great example of how creative work can draw deeply from earlier art, without “commenting” on it in a postmodern way, but simply by absorbing what was most powerful in the past and extending, deepening it, personalizing it.

Everything must go. Maybe.

In a recent story in the New York Times about Detroit’s dilemma, whether to sell its art collection to pay its debts in bankruptcy, Robert Frank suggests that the art market ought to be seeking out lesser-known work by emerging artists rather than bidding up the value of “masterpieces” in turf battles for trophies. Yet what the article emphasized for me was how dismal it is, indeed, to reduce a work of art to its economic role in the world, as if its price is an accurate way to express its value in the lives of those who make or encounter it. “Yes, communities benefit from famous paintings, but they also benefit from safer roads and better schools.” Oh well. On a completely different note, apparently, if Detroit decided to hold its garage sale, I might actually be able to own Bruegel’s Wedding Dance for $200 million? That would be the highest price ever paid for a painting, but somehow it sounds like a bargain in a world where you add a trillion here and a trillion there and pretty soon you’re talking about real money. From the article, whose opening summarizes the plight of talented artists working in the “long tail” of the market everywhere:

Yet the point remains that prices affect the options we face. Relative to famous art, lesser-known works have become much cheaper in recent years, despite no evidence of any decline in their quality. In a rational world, this change would encourage curators to invest more heavily in emerging artists.

Many of these artists produce works that are deeply affecting, yet surprisingly affordable. Talented curators could assemble collections of their art that would delight visitors and draw fulsome praise from critics. And as those works became better known, their value would climb rapidly.

Ownership by public or nonprofit institutions is also not a prerequisite for public exhibition of prized art. The superrich pay so much for these works largely because they are already so famous. Yet being chosen for prominent display in public spaces was how many of these works became famous in the first place. If fewer museums owned them, the rich would have good reason to lend them more often for public display, as indeed many already do, thus preserving and enhancing their value. If sold, many of the institute’s famous works would return as loaners, along with such works from other collections.

If billionaires choose to bid up the prices of trophy art, that’s their privilege. And because most of them will die with large fortunes unspent, they can buy what they want without having to buy less of other things they value. But because money for worthy public purposes is chronically in short supply, city officials and true philanthropists must grapple with agonizing trade-offs.

Yes, communities benefit from famous paintings, but they also benefit from safer roads and better schools.

Galleries galore

Reports on the death of the art gallery, as an institution–as opposed to the air fair–may be premature, though I do see a lot of struggle. I got a going-out-of-business flyer yesterday from what has traditionally been the most commercially successful, if less discriminating, galleries here in Rochester. It was advertising a 75% off sale. For art. It has been going out of business, it seems, for well over a year now. I wonder if that could simply be an ongoing stance that works as a business model. Going out of business, but never quite gone.

Reports on the death of the art gallery, as an institution–as opposed to the air fair–may be premature, though I do see a lot of struggle. I got a going-out-of-business flyer yesterday from what has traditionally been the most commercially successful, if less discriminating, galleries here in Rochester. It was advertising a 75% off sale. For art. It has been going out of business, it seems, for well over a year now. I wonder if that could simply be an ongoing stance that works as a business model. Going out of business, but never quite gone.

On the more hopeful side, the New York Times published, a few days ago, a collection of pieces celebrating how New York City remains the center of the art gallery world, even if it hasn’t remained the center of art world as a whole: which the article points out has spread to Berlin, London, and other parts of the globe. I intend to read through this survey of the gallery scene in detail, before my next visit to Manhattan in a couple weeks. I know my haunts in Chelsea, but it would be fun to venture elsewhere. My favorite line from the bunch, from Holland Cotter about the current show at Zwirner: “Mr. Wolfson himself appears in mock-punk drag, as if to finesse illusions about art’s connection to some mythically resistant underground.” Resistance is just a pose, earthling, especially if you’re represented by the new power in art commerce. It would appear that the last of the underground would appear to be leaving New York shortly: Clayton Patterson.

Postal windfall

From a friend, who lives in a town in Tennessee and sends me links I often comment on here and who acts as voluntary (Tennessee is the volunteer state) copy-editor for this blog.

From a friend, who lives in a town in Tennessee and sends me links I often comment on here and who acts as voluntary (Tennessee is the volunteer state) copy-editor for this blog.

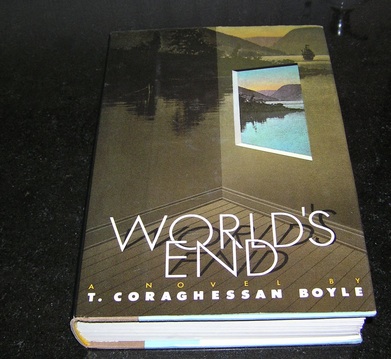

Walt: Got a package in the mail containing a letter from the Post Office. “The enclosed material was discovered loose in the mail and has apparently become separated from its packaging. If you feel the entire contents has not been recovered… Please accept my sincere apologies… The loss of or damage to any piece of mail is as disappointing to us as it is to our customers… Signed, Supervisor, Undeliverable Mails.” In the package, a hardcover book: “World’s End” by T. Coraghessan Boyle. If it was “loose in the mail…separated from its packaging”, how did they figure out it was meant for me? Anyway I didn’t order it, so how did they figure out it was meant for me, which it wasn’t?

Dave: Apparently, you have been identified as the only person in town about whom it’s considered remotely possible you would be reading him.

Walt: Hey, Frank, it says, “In rich and sensuous prose, studded like a mace with knobs of black humour, Boyle invokes the colonial past … Not since Thomas Pynchon has any fresh American writer so cunningly lit the fuses of history so that they detonate in time recently past.” Well hell, send it to that Thomas guy over on Tyler, who else?

Dave: You, yourself, are studded like a mace with knobs of black humor, so . . . good detective work.

Getting into the Met

Cinderella’s odds of getting her foot into the door at the Metropolitan rise considerably when it’s bare. From the Sunday Book Review: “Less than 5 percent of the artists in the Modern Art section are women, but 85 percent of the nudes are female.”

My stop is an F minor

FROM: Sound Opinions #431

James Murphy may have mothballed LCD Soundsystem, but he wants you to make some underground music for him. If it works, music will rise up like steam from those grates where you hear the subway passing below your feet. Every subway station will have its own song, which it will compose and play spontaneously, at the touch of a passenger’s body, passing in and out of the station. That has to qualify as a public art project. no? Those astute Chicago boys at Sound Opinions publicized this recently in one of their interviews:

James Murphy: I’m trying to do music for subways.

SO (joking): You’d have to be really loud.

JM: I’m serious.

SO: Really?

JM: I’ve been trying for 14 years to make the turnstiles make music. I want to make every station in New York have a different set of dominant keys. I want each subway station to make music in a particular dominant key so that when someone grows up and hears a piece of music he might think, “Wow, that’s like Union Square.” When you go through a turnstile it would beep in a certain note. The root note would have a higher percentage of going off, and then a third and a fifth note. (Editor’s, uh, note: That would make a major chord. ) Each turnstile would have a random note generator based on a certain percentage. During rush hour, they might make a beautiful sound. New York is a brutal city, and I love it, but this would be one little bit of kindness.

SO: It could start in Jersey on the PATH trains, and New York would get jealous.

JM: You could have your active brain turned off but hear the notes of your station and wake up from your book and know it’s time to get off. Of course I’m envisioning a New York where everyone’s reading on the train.

Or they could have LCD Soundsystem in their earbuds and all that body music would be for naught. Wish somebody would take him up on it. What are the odds De Blasio would even consider it?

Calling all fellow canaries . . .

You can find a few thoughts on how the Internet and technology are eroding the middle class–and democracy along with it, if you follow the logic–in this interview with Jaron Lanier from Salon. It offers musings from Lanier, an artist and musician and computer scientist, as well as a professional contrarian, on how the creative class is the canary in the digital coal mine. But he’s addressing every species of bird: “Because technology will get to everybody eventually.” (His thoughts on authorship and books is especially noteworthy, on how books, as a medium, are connected to “personhood” more than as a vehicle for imformation. Which for me is why a painting matters.)

All of this ought to be weighed against how much the Internet actually makes possible for an artist. For Lanier, who is interested primarily in musicians, the Internet offers a ton of exposure but doesn’t create an economic model to sustain the music. It’s a truism now that bands have to go on the road perpetually and live off gate receipts and t-shirt sales, rather than through sales of what they record in the studio. (There are always exceptions.) I know some artists can actually make a steady income by selling work from their websites, though I doubt that the numbers are large. What the Internet does offer is a way to get one’s work out in front of people, even if it’s only as a reproduction. Yet it also helps enormously in getting the actual work onto walls where people can stand in front of it. Online you can find all sorts of opportunities for exhibitions, both domestic and international. I had a painting shown in London based on a call for entries I found online. This would never have happened without electronic media. Visual art has rarely been a sensible career path. The role of teaching has been crucial as a way to make art and make a living. Art school is as close as you can get to a sinecure that allows enough time to steadily produce art. The only drawback is that it’s incestuous, in a way–educators training future educators how to educate, with output that reaches a tiny circle of devotees, probably more future educators. But maybe that’s the story of most art since painting began, with very few household names emerging into the awareness of a general public.

The larger story here is how technology is undermining most of our assumptions about individual effort, in any field, and its connection to money. Lanier talks a lot about Eastman Kodak, here in my back yard, and how Instagram with its 13 employees isn’t exactly an adequate substitute for the 140,000 generously paid Kodak workers whose jobs will never come back. It’s interesting that Lanier picked Kodak because it was a purely capitalistic enterprise that cared, in a serious and tangible and institutional way, for it’s workers–partly to keep them from unionizing, but also because George Eastman created that kind of culture. He was among a number of CEOs who felt responsible to their communities and their employees, and they rewarded people accordingly. Frank Gannett, who ran Gannett Co., headquartered here for decades, was exactly that kind of CEO, as well, and Joe Wilson at Xerox, too, in the early years when it was based here. There are still CEOs like that around, John Mackey for example, but not enough. What’s interesting is how Lanier looks at how technology, and the economy it creates where money rises into a few pockets, has made subsistence harder, not easier, for lone artistic strivers. He tends to focus on musicians. For him, their current struggle is just a prelude to what everyone is going to be enduring as technology narrows the distribution of income and eliminates jobs. I liked his sardonic take on Google’s dictum that “information wants to be free”: which means my information, your information, and everyone else’s can be freely sold by Google, to advertisers–and Google’s few beneficiaries are the only ones getting wealthy in the process. Facebook: same thing. On the other hand, Facebook and Twitter foster democratic upheavals in the Middle East. They do what they are meant to do very effectively, but economically they’re parasitical. They just aren’t paying the producers, you and me, for what they make from our information. It’s, uh, free.

My apologies to Salon, and Lanier, for quoting so much of this out of its context. Right after he says information shouldn’t be free, I borrow some of his and pass it along, for free. And there you go . . .

From the interview:

In a raw kind of capitalism there tend to be unstable events that wipe away the middle and tend to separate people into rich and poor. So these mechanisms are undone by a particular kind of style that is called the digital open network.

Music is a great example where value is copied. And so once you have it, again it’s this winner-take-all thing where the people who really win are the people who run the biggest computers. And a few tokens, an incredibly tiny number of token people who will get very successful YouTube videos. Everybody else lives on hope or lives with their parents or something.

One of the things that really annoys me is the acceptance of lies that’s so common in the current orthodoxy. I guess all orthodoxies are built on lies. But there’s this idea that there must be tens of thousands of people who are making a great living as freelance musicians because you can market yourself on social media. And whenever I look for these people – I mean when I wrote “Gadget” I looked around and found a handful – and at this point three years later, I went around to everybody I could to get actual lists of people who are doing this and to verify them, and there are more now. But like in the hip-hop world I counted them all and I could find about 50. And I really talked to everybody I could. The reason I mention hip-hop is because that’s where it happens the most right now.

So when we’re talking about the whole of the business – and these are not 50 people who are doing great. Or here’s another example. Do you know who Jenna Marbles is? She’s a super-successful YouTube star. She’s the queen of self-help videos for young women. She’s kind of a cross between Snooki and Martha Stewart or something. And she’s cool. I mean, she kind of helps girls with how to do makeup, and she’s irreverent. She’s had a billion views.

The interesting thing about it is that people advertise, “Oh, what an incredible life. She’s this incredibly lucky person who’s worked really hard.” And that’s all true. She’s in her 20s, and it’s great that she’s found this success, but she makes maybe $250,000 a year, and she rents a house that’s worth $1.1 million in L.A.. And this is all breathlessly reported as this great success. And that’s good for a 20-year-old, but she’s at the very top of, I mean, the people at the very top of the game now and doing as well as what used to be considered good for a middle-class life. And I don’t want to dismiss that. That’s great for a 20-year-old, although in truth, in my world of engineers that wouldn’t be much. But for someone who’s out there, a star with a billion views, that’s a crazy low expectation. She’s not even in the 1 percent. For the tiny token number of people who make it to the top of YouTube, they’re not even making it into the 1 percent.

The issue is if we’re going to have a middle class anymore, and if that’s our expectation, we won’t. And then we won’t have democracy.

I have 14-year-old kids who come to my talks who say, “But isn’t open source software the best thing in life? Isn’t it the future?” It’s a perfect thought system. It reminds me of communists I knew when growing up or Ayn Rand libertarians. It’s one of these things where you have a simplistic model that suggests this perfect society so you just believe in it totally. These perfect societies don’t work. We’ve already seen hyper-communism come to tears. And hyper-capitalism come to tears. And I just don’t want to have to see that for cyber-hacker culture. We should have learned that these perfect simple systems are illusions.

For more along these lines, look here. His notion of micro-payments sounds interesting, but how would that work? I get a fraction of a penny for everyone who clicks on a hi-res JPEG of a painting I’ve done? It doesn’t seem like much of a substitute for an essentially tenured job at Kodak in the 60s and 70s.

The architecture of the internet must support a global, universal micropayments capability. In this way, anyone could charge for information made available online, whether it is music or a program for a future robot. A silly YouTube-like prank might generate a windfall for a silly teenager, while a scholar’s writing might be only occasionally accessed, but over a long period might still generate enough income to be of use. People could then re-create the best social formula that has been achieved thus far in human experience. Middle class people could own something- the information they produce- that would give them sustenance as they have children and age.

In order for this scheme to work, there would have to be some structural changes introduced gradually, as I explain in the book (You Are Not a Gadget). This direction is the only way to create a human-centric internet, instead of one that serves the cultists who believe in information more than people. It would not attempt to make information free, but instead make it affordable. It is worth noting that this is exactly how the web would have developed if the initial design proposal for it, dating back to the 1960s, had been carried out. It is the obvious way to design the network if people are your top priority.

The Rush

Rush Whitacre’s solo show, Shadows, is opening on March 28 at the Parkersburg Art Center in West Virginia. He’s been planning this for quite a while. I was worried he’d quit painting altogether because he’d gotten so focused on his writing when he left Brooklyn and returned to Ohio to be near his aging father in 2012. Leave it to Rush to give his show a tagline that quotes a famous line from a Depression-era radio drama. He answered a few questions for me:DD: It looks big from the photographs of the space.RW: It’s my first solo exhibition. Huge space, 4,500 square feet, with 15 large walls, 15 small walls. I’ll be exhibiting a lot of shadow art, drawings old and new, some drawings from my book Mabast. Four of them are five feet by seven feet, charcoal on moonstone paper.

DD: Some big paintings too no doubt.

RW: All of the LifeCycle flower paintings will be in the show, a triptych of roses, 15′ x 8′, irises 22′ x 12′, sunflower 11′ x 24′ (the size of Picasso’s Guernica), daffodils 4′ x 6 and a new dead flower 11′ x 13′. Also in the show will be a painting of a public sculpture in Marietta, Ohio carved by Mount Rushmore’s sculptor. Several paintings of scenes from my novel will have similar proportions. The smallest is 2′ x 6′.

Beauty, happiness, innocence, joy, and love

Wonderful to see Agnes Martin’s work honored as the Google search engine logo today. Look in vain for anything that will convey the beauty and stillness of her paintings on the Web. It’s yet another example of how little a reproduction can convey what an actual painting can communicate–in a particular and unique place and time, where your body is also required. Sorry Internet, deal with it. Her subtle application of color eludes photographs and computer screens. I saw her paintings on a visit to Santa Fe with Donna Rose, when we drove to Santa Fe from Albuquerque, where we’d flown to hear Dave Hickey interview Ed Ruscha at the Tamarind Institute. Martin’s work has an amazing sense of depth, despite the fact that she’s essentially working in a minimalist tradition. Her surface doesn’t appear flat at all, and the simple forms seem both distinct and yet continuous with everything else in the picture. She felt she belonged with the abstract expressionists, with a spirituality that shunned intellectualism. As the Pace Gallery wonderfully put it on their website for a show a decade ago: “Martin has historically explored non-referential and transcendent themes of Beauty, Happiness, Innocence, Joy and Love.”