Archive Page 25

July 18th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Fort Howard, Rear View, oil on panel, Matt Klos

Jim Hall has a great selection of previously exhibited work on the walls at Oxford Gallery this summer in a show titled “Reprise“. Some of my favorite paintings from previous shows are on view, as well as many I overlooked. The one above, a small work from Matt Klos, came from the series he did of scenes in Baltimore’s Fort Howard.

July 16th, 2015 by dave dorsey

The artist’s reception at the 79th Butler Midyear Exhibition at the Butler Institute of American Art is this Sunday afternoon. The collector who bought the painting and loaned it to the museum for the exhibition pointed out to me yesterday that they featured it on their page announcing this year’s show. I’m honored. I wish very much that I could attend on Sunday but I have a previous engagement.

The artist’s reception at the 79th Butler Midyear Exhibition at the Butler Institute of American Art is this Sunday afternoon. The collector who bought the painting and loaned it to the museum for the exhibition pointed out to me yesterday that they featured it on their page announcing this year’s show. I’m honored. I wish very much that I could attend on Sunday but I have a previous engagement.

July 13th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I’m down with Opie. Yeah, you know me.

It’s July and I’m fishing for ideas by producing a lot less of everything than usual. I’ll be back. (In August.) Those are nice Chuck Taylors on Ron Howard. The high tops back then weren’t as high as they are now.

July 3rd, 2015 by dave dorsey

|

I’m in California for a week with my family, but I thought I would pass this notice about a show back home along, something I’d like to see when I get back next week. Artists include: Betsy Lee Taylor, Jean K Stephens, Cathy Chin, Lanna Pejovic , Denise Heischman , Bob Dorsey, Carol Acquilano, Kathryn Bevier, Gloria Betlem, Alan Singer, Gail Thomas, Amy Stummer, Robert Heischman, Jane O’Donnell, Rebecca DeMarco, Bill Stephens, Jim Mott, Phyllis Bryce Ely, Paula Crawford and more.

This is an exhibition of “plein air” paintings and drawings by regional and national artists invited to submit art all summer long in an ever changing exhibition. Works will be framed or presented unframed and may even reflect unfinished sketch states as well as fully finished.

The exhibition is designed to encourage artists to get out and paint and present their work without the usual formality and cost of showing.

The gallery will accept new works from our invited artists each Thursday for the duration of the show and so it will “organically grow” throughout the season.

For more information please contact Denise Heischman or Mary Reakes at:

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2015, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

Mill Art Center & Gallery

61 North Main St.

Honeoye Falls, NY 14472

|

|

|

|

June 30th, 2015 by dave dorsey

From the Sad Stuff on the Street blog.

Sad stuff on the Street.

June 23rd, 2015 by dave dorsey

After my last show at Oxford, I decided to tackle the most ambitious painting I’ve ever done. It’s another in the series of tabletops I’ve been doing for a long time–I did the first one, back in the 90s. Why I keep returning to the format isn’t entirely clear to me, other than to say I don’t feel I’ve exhausted the rewards this template, with its unusual downward-looking perspective, a literally bird’s-eye view of a tabletop. What’s unusual, this time, is how long I expect to work on the painting. First, I’m going to spend more time on each part of this painting than I have before, developing the image as slowly as it requires, so that every element gets as much attention as all the rest. I’ve already put about six weeks into it and don’t expect to be done until the fall, partly because the summer always pulls me away from the easel for several weeks every year, but mostly because it’s a set of complex objects requiring gradual, painstaking development. While I’m doing it, I’m going to try to clarify to myself how and why I started doing this sort of image, why it allowed me to absorb certain influences and incorporate them into my own work, and what sort of meaning the images seem to have, even though I have been creating them simply as a way of addressing formal challenges, not conceptual ones. My blog output is likely going to lighten up since my energy goes first to this painting, and hopefully some small ones I’ll be able to do along the way as I finish this. That’s Poppy, the newest member of our clan, peeking out at you from inside my iPhone.

June 15th, 2015 by dave dorsey

The Doge’s Palace, John Ruskin

There’s an interesting overview of how John Ruskin took the perception of beauty as a foundation for social reform here. His drawings are exceptional; the ones of Venice remind me of Canaletto. I’m not sure I share his view of beauty and his passion for reform: the perception of ugliness often means you aren’t seeing what’s actually there. There’s delight in reading Salinger’s catalog of a medicine chest’s contents in Franny and Zooey, but I doubt it would have passed the Ruskin test for beauty. But he seemed to value the act of paying attention as the root of what’s good in life, and art was a way of practicing it.

So Ruskin thought it helpful for us to observe and be inspired by nature (he was a great believer that everyone in the country should learn to draw things in nature). He wrote with astonishing seriousness about the importance of looking at the light in the morning, of taking care to see the different kinds of cloud in the sky and of looking properly at how the branches of a tree intertwine and spread. He took immense delight in the beautiful structures of nests and beavers’ dams.

June 13th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Novalis

A finely written piece, again from The Paris Review, from a young Rochester novelist on how costly ultramarine paint once was. It’s fascinating how an artist using cheaper substitutes would be taking terrible career risks. Now it’s one of the less expensive paints, something I use constantly but mostly to mix with raw umber to get an equivalent for very dark grays and a substitute for black. There are some inspiring paeans to ultramarine here, though the great poet of blueness is missing: the German scientist, Novalis and his “blue flower,” the symbol of German Romanticism. Yet for me, ultramarine isn’t “true blue.” It’s a blue that leans toward purple, and you’ll find it far more often in nature than a purely neutral blue, which I’ve found nearly impossible to locate out in the world. In our garden, I’ve seen what I considered a pure blue only once in a delphinium that survived our winters only a couple years and was impossible to find again. There was almost no trace of green or red in its blue flowers. Blue has no more appeal for me as a color than anything else in the spectrum, yet it was amazing to see blue, and just blue, itself out there in the yard, rather than some commonplace blue tinted toward of violet or purple, as ultramarine is. From the essay:

Michelangelo couldn’t afford ultramarine. His painting The Entombment, the story goes, was left unfinished as the result of his failure to procure the prized pigment. Rafael reserved ultramarine for his final coat, preferring for his base layers a common azurite; Vermeer was less parsimonious in his application and proceeded to mire his family in debt. Derived from the lapis lazuli stone, the pigment was considered more precious than gold. For centuries, the lone source of ultramarine was an arid strip of mountains in northern Afghanistan. The process of extraction involved grinding the stone into a fine powder, infusing the deposits with melted wax, oils, and pine resin, and then kneading the product in a dilute lye solution. European painters depended on wealthy patrons to underwrite their purchase. Less scrupulous craftsmen were known to swap ultramarine for smalt or indigo and pocket the difference; if they were caught, the swindle left their reputation in ruin.

June 11th, 2015 by dave dorsey

On my recent visit to the home and studios of Bill and Jean Stephens, I got a look at a wall full of work Bill has been doing. The little grove of trees (where Jean built her human-sized nest of branches and twigs) fascinates Bill, and he’s been doing an extensive series of paintings and drawings inspired by it. Recently, he took a small suite of these paintings and sanded them down, erasing upper layers of the paint and revealing far more abstract and beautifully colored areas underneath: from representation back to abstraction with a technique that almost fits into the Japanese gutai sense of letting the erosion of materials become an essential part of how a work of art will turn out. In this case the erosion is intentional. I really like what he’s ending up with, though he may be tempted to reverse course and start finishing things more. But unfinishing a painting is an interesting idea. Take it back in time to something that wasn’t actually visible at any point along the way.

June 9th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Jim Mott’s saguaro from his stay in Tuscon

Jim Mott, my friend the itinerant painter, has modified his M.O. just slightly. He’s an itinerant painter who now, sometimes, becomes a . . . hm. . . sojourning painter, I guess. Not to put too fine a point on it, technically speaking, he goes somewhere now and hangs around longer. Until lately, he’s been doing very long-distance laps for the sake of his painting. He’s a soul with a stopwatch ticking for the act of seeing (which is life, isn’t it)? He usually goes to a faraway place, like Washington state, and then comes home slowly, like Odysseus (but without nearly as much bloodshed along the way), through Idaho and Colorado or whatever, Wyoming, say. He stays with people who feed him in exchange for a painting of their surroundings. No money changes hands. Only hospitality for a tribute to the ordinariness of the place.

In Arizona not too long ago, he tried a new tack. He stuck around for a month and did minature Joseph Campbell day-trips out and back, over and over again, right around Tuscon. He came home to Rochester with shots of some fresh work, and I told him I thought it opened up a new way of exploring his relationship with people and landscapes far from home. Every day he would generate a new GPS point on the map, using a computer–would this count as some kind of self-fulfilling sortilege? I hope so. It would be cool and James Merrill-y to think of it that way, but it was digital divination as Stanley Kramer might have filmed it: his lottery delivered him to the runway of an airport one day and a dried-up aqueduct on another. (Go to the train station and paint it, Charles Hawthorne told his students. Go to this ditch and paint it, Jim’s computer told him.) Sticking to plan and principles, he got out his paints and looked hard. Which means the looking is much easier and rewarding, for all the rest of us, now that he’s back. I’ll never think of my Garmin app in the same way again.

June 7th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Some of my favorite paintings by Jean Stephens are the ones she’s done of bird’s nests. I recently visited her home and studio, where she lives and works with Bill Stephens in Honeoye Falls, south of our home in Pittsford–I spent most of my time talking with him and Bill Santelli. It’s a fantastic place, secluded at the end of a private lane, with an artificial pond infiltrated by rushes and cattails, bird houses everywhere, and a long slope that descends from behind their place to a small grove of neatly, evenly spaced trees. In this little copse, Bill rakes the leaves into long, sinuous mounds that meander around like the paths of enormous moles. Jean has been taking all the dead limbs and twigs and building a human-scaled nest. I wanted to take it home and curl up inside it.

June 5th, 2015 by dave dorsey

The Mezzanine is one of my favorite novels, which is why I like to think of Nicholson Baker as a Rochester homeboy. The entire novel took place on an escalator that once existed downtown here. From the intro to an interview with Baker in The Paris Review:

The Mezzanine is one of my favorite novels, which is why I like to think of Nicholson Baker as a Rochester homeboy. The entire novel took place on an escalator that once existed downtown here. From the intro to an interview with Baker in The Paris Review:

Few other authors would notice, as Baker did in The Mezzanine, that late-twentieth-century American men trying to pass through a door at the same time always say “oop” to each other instead of “oops.” After some twenty-five years of writing, Baker’s reputation is as unusual as his work. He has been praised, widely and enthusiastically, for his style, humor, originality, and empathy. (As Martin Amis once put it, “Throughout his corpus there is barely an ordinary sentence or an ungenerous thought.”) At the same time, some critics have very publicly loathed a handful of his books, most vociferously Vox(“tedious”), The Fermata (“repellent”), Checkpoint (“scummy”), and Human Smoke(“childish”). Many of Baker’s talents are self-consciously small: meticulously inventive phrasemaking, a masterfully intimate tone, and a superhuman gift for observation. He has a Dutch-painterly reverence for everyday rituals and objects—a belief that they will start to glow with significance if we only pay close enough attention. This has left Baker open to the charge that the work itself is trivial, quaint—a bubble of old-fashioned belletrism floating through a harsh modern world. (Leon Wieseltier, writing in The New York Times, once called Baker’s novels “creepy hermeneutical toys.”)

What’s disguised by Baker’s cheerful tone, however, is his passionately sustained conviction that we should honor the details of our lives rather than getting carried away by projections and abstractions. In this quest, Baker has seemed continually willing to risk puzzling his fans and inflaming critics; he has shown an indifference to publishing fashions that few authors could have sustained. One index of this independence is that, although Baker has been published for his entire career in magazines such as The New Yorker and The Atlantic, he has never held a staff position. “I felt I had to be someone who would leap in from outside,” he told me, “and do some nutty thing and then run away cackling.”

Baker is fifty-four years old, but you can still see the teenager in him: he is self-consciously tall and shy, and his face turned red, often, when we talked about his books. He lives in a rambling eighteenth-century house on the border of Maine and New Hampshire. We spoke there for several hours, first in the kitchen and then in the living room, next to the fireplace in front of which he wrote A Box of Matches. Later, Baker drove me to a restaurant in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where, as we entered, a man exiting at the same time very distinctly said, “Oop!”

May 30th, 2015 by dave dorsey

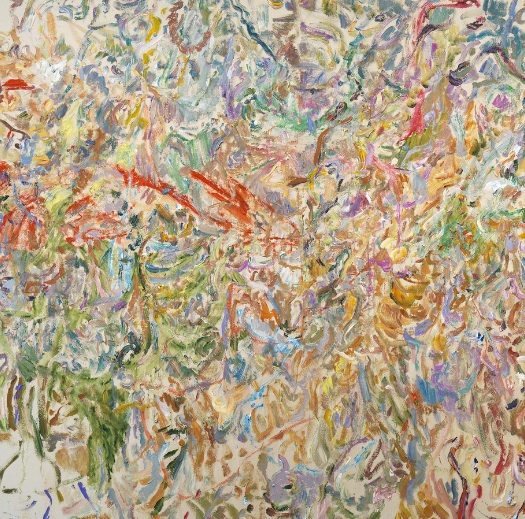

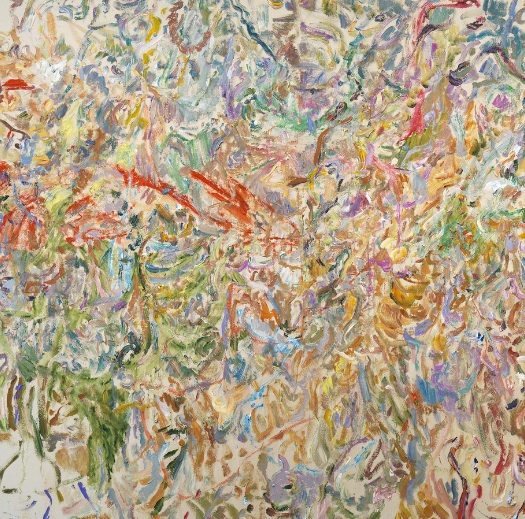

Angle of Landscape, detail, Larry Poons

A nice reflection in Artsy about the Larry Poons show at Danese, one of my favorite galleries in NYC. I saw the last show of his latest work there a while back. Like Thiebaud, he’s as prolific as ever, regardless of age. The work seems somewhere between late Monet and 50’s AbEx, with his color reaching back to the French, for me at least. Bonnard, maybe?

May 28th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Plaid Pantry, oil on plywood, (2010), 9 7/8″ x 10 3/8″, David Rosenak, at Portland Art Museum

“It can be such an insane, strange undertaking to be an artist.” –Sarah F. Burns

But it can be worth it. To wit, from Sarah F. Burns:

David Rosenak has become sort of a mentor (for me) or an example of having integrity as an artist. So, to set the stage for how he has been an example, I’m going to share where my head is/was. I felt — and still feel — internal pressure to legitimize my obsession with art by turning it into a business. But I’m not capable of “branding” myself with a style and making pieces that are predictable and popular. I absolutely think art is a noble profession and if people sell their work well enough to put food on the table, I think that’s awesome! It’s great when art can be appreciated widely, but if you’re an artist you also know there’s an icky, slippery slope . . . when you’re making art mainly for other people. On the other hand, most of us are not simply expressing ourselves for its own sake, but trying to reach out and connect to some unknown viewer in an authentic and sincere way.

(untitled) 2013, oil on plywood, David Rosenak, 18 3/8″ x 16 3/4″

Along with that struggle, there is the battle for technical skills, real ideas and the essential but unpredictable spark of magic that makes good pieces work. It can take years to even come close to making something really special. Years of self-examining, persistent, steady work. To be really great, you have to start young and have some successes; many of those successes are self delusions, but that’s no matter, they keep you going, keep you pushing forward. After all that you still may not have achieved something great, or may not get recognition until you’re gone. It can be such a strange and insane undertaking to “be an artist”.

So here I am, needing to justify all this by making it a business and I meet David. The time when I meet him and first see his work is at a point where he has achieved something special through years of trial and error and persistence. His work is desired by collectors, galleries want to sell his work, and David simply says “No, thank you”. He does not sell his work. I repeat — his paintings are not for sale. He has goals for his work, for sure. He doesn’t create it “for himself” – as the corny line goes. He wants it to be seen in the world by as many people as possible. He knows how long they take to make, how hard he worked to make something he is truly proud of and he wants to cast them in a place where they have the best chance to grow.

And he knows they are precious. They take months and months to complete. He puts scores of hours into each piece. Because time stops for no man, his window for making them is pretty small – as it is for us all – but heightened by the fact that ten years ago David discovered he has Parkinson’s disease, which causes tremors, making painting tiny things a challenge. When he first noticed the tremor it was in his right hand, and after three years he trained himself to paint with his left. (This is so typical of David. Persistent.) Now he can only paint on his good days, still with the left hand.

More interesting things about David: he is color blind. When David was young and testing out his influences, he tried a few paintings in the style of Wayne Thiebauld, but since Thiebaud’s thing has a lot to do with color, David realized he was trying on someone else’s shoes (we all do that when we’re young, but some of us never grow out of it). Then he noticed his primary teacher was making some greyscale paintings, and he realized he’d been fighting a battle with color he had no hope of winning, so he switched to greyscale in 1981 and hasn’t looked back.

David has painted cityscapes since the late 80’s; he showed me a few scenes near his house in a medium sized scale. And they were cool. Then he made them small (nothing larger than 20″ and most average 10″ on the long side) and bam! They suddenly really worked. As the scale was becoming more intimate, the subject moved closer and closer to his home. All the views are of his back yard or his view toward downtown Portland (Oregon). Since he has the subject, scale and approach settled, he is focusing on compositions, and they get more and more mature. He likes to joke that he is essentially making the same painting over and over again in an attempt to improve it. And he has many plans for new paintings within that framework. The adage of freedom coming from limitations is really true, I guess.

Since his subject matter is his yard and what he can see from it, it’s useful to say something about his home. He has a wild, artsy little compound in SE Portland, full of cats and dogs and amazing plants, and all tended to by his neighbor and long time friend, Moe (Maureen). Moe is a gardener and you see in the paintings records of Moe’s work and their friendship. David lives kind of like a cat, moving around his territory, napping, enjoying bits of shade or bits of sun, walking over to his studio a few blocks away to paint, taking the bus across the river to his day job. His paintings are the way a cat would record things because they feel so still, yet so full of life. Like a cat, they contain long moments of stillness while being ready to spring to action at any second. They’re also neutral like a cat. They’re not saying, “Let’s go do this!” or “Think this!” but, “This is fine as it is. I’ll find a comfortable place here.” They say, “I see it all, and it’s fine.”

May 25th, 2015 by dave dorsey

A portrait of Lenin, from the photograph of him lying in state. This is one of those paintings that makes you want to pick up a brush immediately. It reminds me of Michael Borremans, who had a knock-out show at Zwirner a while back, stunningly good, but since then. . . hm.) And this is stronger than his work. With both, less is more. I like Ghenie’s sense of humor. This interpretation of Lenin’s dead face reminds me of Blake’s life mask.

May 22nd, 2015 by dave dorsey

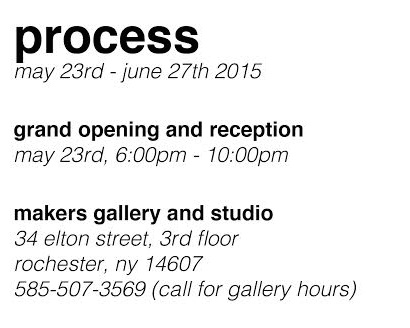

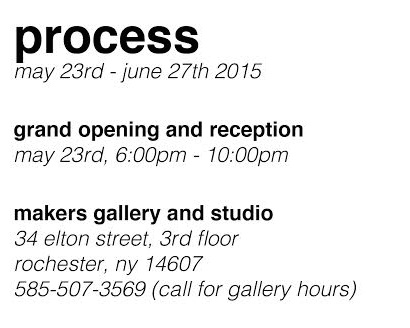

This sounds like a great idea, from the email I got:

Join us at Makers Gallery and Studio, Saturday May 23rd from 6-10pm for our inaugural show entitled process. We are located in the Neighborhood of the Arts on the third floor of 34 Elton Street, Rochester (parking is directly across the street). Avvino will be providing drinks and hors d’oeuvres.

Makers Gallery and Studio was founded by Alexander Gruttadaro, Anni Gruttadaro and Edward Zachary Graham. This studio is going to open its doors to a variety of art classes and workshops, taught by Alexander, Sari Gaby and other great local artists.

This first show is about beginnings: the beginning of this studio and an exploration of the artists process. Each artist will feature works in progress as well as finished works, to develop a better understanding of how and why they create. Each artist will allow you a look into their intimate space, as a modified version of their own studio. Our aim is for the viewer to better understand how work is created, so you can not only admire the finished product, but also the steps each artist takes on their journey. Each featured artist has a unique and recognizable style, giving depth and variety in this first show.

We hope to see you at the first of many exhibitions and look forward to being a collaborative part of the special art community Rochester is so well known for.

If you have any questions or wish to unsubscribe to our e-mails, please contact us at the information provided below. We look forward to seeing you on Saturday!

Regards,

Sari Gaby,

Alexander Gruttadaro

Todd Stahl

Bill Stephens

May 21st, 2015 by dave dorsey

After four decades of painting—actually a little more than that—it might be something of a mystery to a non-painter why I would put in five or six hours painting today, before or after three or four hours of doing work that brings in most of the money I need to pay bills. I sold seven paintings at my last show, so far my most successful show, measured in income, and yet through the sale of artwork I make only a small portion of the modest amount my wife and I need to continue living the way we do. Still, my ideal day is to paint for more than half of my working hours and then do what other work I need to do in order to keep my income at a level that sustains us. Why paint, though? Why not put those hours into something more lucrative? The short answer is, because I love it. It’s a necessity for me. But that’s little more than a tautology: I paint because I need to paint. Why do I love it? Why does any painter make pictures? What does it all mean? (And let’s be honest. I don’t love all of it. As Bill Santelli put it earlier today, there are long hours that feel like mowing the lawn with scissors.)

After four decades of painting—actually a little more than that—it might be something of a mystery to a non-painter why I would put in five or six hours painting today, before or after three or four hours of doing work that brings in most of the money I need to pay bills. I sold seven paintings at my last show, so far my most successful show, measured in income, and yet through the sale of artwork I make only a small portion of the modest amount my wife and I need to continue living the way we do. Still, my ideal day is to paint for more than half of my working hours and then do what other work I need to do in order to keep my income at a level that sustains us. Why paint, though? Why not put those hours into something more lucrative? The short answer is, because I love it. It’s a necessity for me. But that’s little more than a tautology: I paint because I need to paint. Why do I love it? Why does any painter make pictures? What does it all mean? (And let’s be honest. I don’t love all of it. As Bill Santelli put it earlier today, there are long hours that feel like mowing the lawn with scissors.)

I’ve been circling around this question for several years here, getting glimpses of an answer from different angles, at least in my case. And, when I have some time, I want to write at length about why painting points to a way of being engaged with the world that seems in greater and greater peril, with the rise of technology. All genuine work is in peril now, but especially craftsmanship rooted in tradition. Matthew Crawford’s new book has much to say about this, as did his first one. What’s become clearer for me are the motivations that don’t drive me to paint. (I might be better off if these other motivations did drive me, but they don’t.) It doesn’t depend on making money, though the income helps considerably and makes it easier to do the work. The metaphor of the pinball game used by the engineers to describe their work in Soul of a New Machine applies here: winning the game is getting to play another free one. It’s self-perpetuating. It doesn’t depend on recognition or exhibitions. Last year, I had work in eight shows—five of them juried. I’ve applied to nine juried shows this year and got into only one. What does that mean? Nothing, in terms of my dedication to painting. I don’t need to hear people talking about me either: my dealer here, Jim Hall, put it succinctly when he said recently that so much art that continues to be made on the assumption that it’s possible to be “cutting edge” often seems to be work created in order to be talked about. Work that offers little purchase for a discursive mind is considered decorative or otherwise beneath consideration. Some of my favorite artists created pictures about which it’s hard to say anything useful other than write a poem to honor them: you see their world and want to live in it by looking at it or singing about it. The foremost example would be Van Gogh, of course, but there are dozens of others. So being talked about doesn’t motivate me—or rather not being talked about has little effect on my eagerness to make a painting.

So, my situation hasn’t changed since the long years when I painted and didn’t show my work. My eagerness hasn’t waned, because the act of making a painting is the point: it’s both the means and the end. When I sit down to paint, I still feel as if there is nothing else I would rather do than make a painting, until maybe, hours later, I get up to make a sandwich, and I’m motivated to start spreading peanut butter instead of paint. Whether I’m recognized or rewarded makes no difference. I painted for decades and rarely showed anything I was doing, partly because I didn’t want to and partly because my sort of representational work seemed to have no place in what was happening in the world of art. It wasn’t until the economy collapsed in 2008 that I got serious about showing and possibly selling work—a pretty funny and Quixotic bit of timing, given the economy since then. But it was a good indication that my motives didn’t grow out of whatever the world was going to give me in return for the work. I guess I’m saying that the motivation to paint is circular. Or is it recursive? I need to paint because I want to keep painting. I need to see what it shows me. Which will get me nowhere, other than where I already am, maybe to see it for the first time. So, for now, I’ll step out of that loop of thinking, and I get back to just doing it.

May 17th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Series Fifth Element (Water), Jose Sanchez (Felox), Medelin, Columbia, oil on board, 21″ x 15.6″

One of two paintings by Jose Sanchez (Felox) chosen for Manifest’s INPA 4.

May 14th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Cantoria Omaggio: Luca Della Robbia, Debra Stewart

The current show at Oxford Gallery, “The Condition of Music,” grows on you. Walk a few circuits around the gallery and spend time with individual work; it will open up and begin to resonate. Some pieces, though, make their impression immediately: Chris Baker adds a poetic twist to  one of his beautifully geometric construction sites by placing a musical quartet of hard-hatted players atop one of his buildings in “Building Suite.” At first you don’t realize they’re there, but then you spot them, letting their concert rain down gently on the work below. It’s a surprisingly poetic touch and reminded me, in a good way, of some of the best New Yorker covers, a meditation on the emotional polarities of city life. Tom Insalaco’s night cityscape opens a colorful new chapter in his work. The heavy traffic on a rainy, twisting highway creates a shining, brilliant-hued study in light and dark, with car lights strung along their lanes like musical notations on a staff. A post-rain rush hour, in what’s probably an early winter dark, never looked so good. Ray Hassard’s “Song” MORE

one of his beautifully geometric construction sites by placing a musical quartet of hard-hatted players atop one of his buildings in “Building Suite.” At first you don’t realize they’re there, but then you spot them, letting their concert rain down gently on the work below. It’s a surprisingly poetic touch and reminded me, in a good way, of some of the best New Yorker covers, a meditation on the emotional polarities of city life. Tom Insalaco’s night cityscape opens a colorful new chapter in his work. The heavy traffic on a rainy, twisting highway creates a shining, brilliant-hued study in light and dark, with car lights strung along their lanes like musical notations on a staff. A post-rain rush hour, in what’s probably an early winter dark, never looked so good. Ray Hassard’s “Song” MORE

May 13th, 2015 by dave dorsey

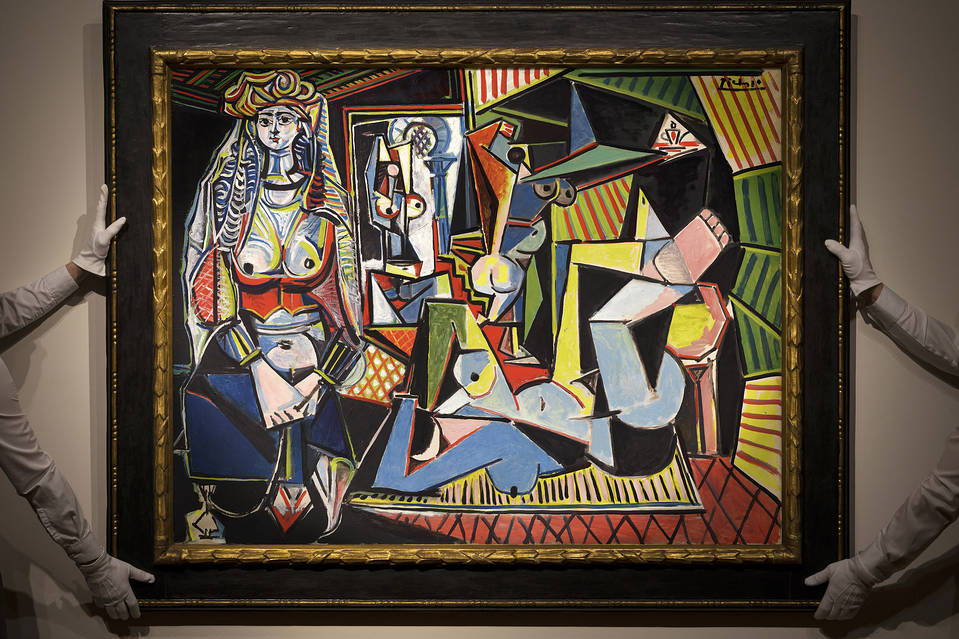

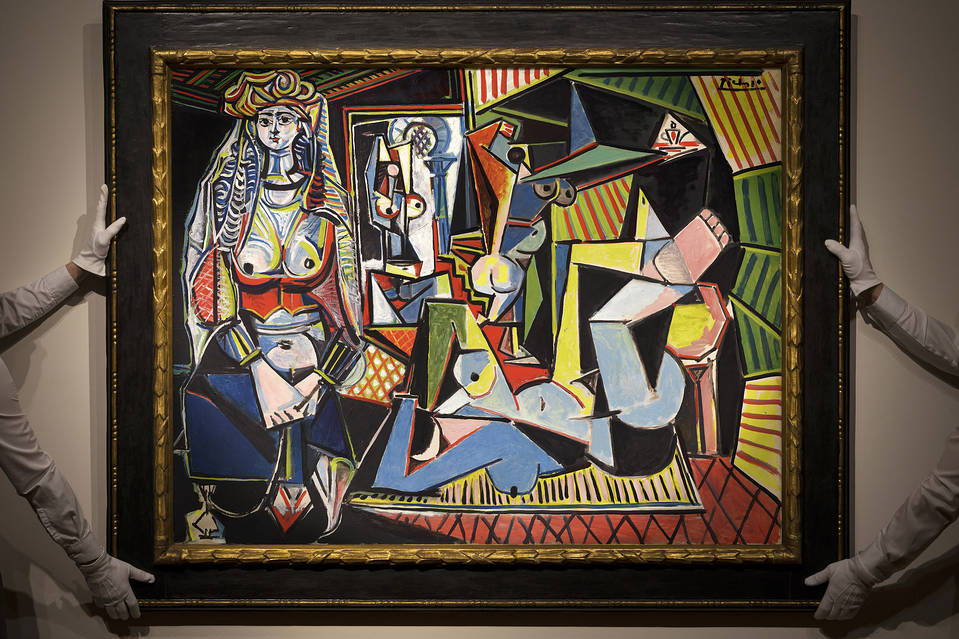

Women of Algiers (Version 0), Picasso, $179 million

This is an interesting perspective on the bull market for enormously expensive, high-end art. From the New York Times. The analysis of the fractal patterns of income distribution in the highest percentiles isn’t something I’ve read before:

The astronomical rise in prices for the most-sought-after works of art over the last generation is in large part the story of rising global inequality. At its core, this is the simplest of economic math. The supply of Picasso paintings or Giacometti sculptures (one of which sold for $141 million in the same auction this week) is fixed. But the number of people with the will and the resources to buy top-end art is rising, thanks to the distribution of extreme wealth.

One of the most important findings of the leading economists who study inequality is that wealth and incomes at the very top are “fractal.” What they mean is that when you zoom in on the upper end of wealth distribution, patterns repeat themselves in an ever more finely grained pattern.

Partners at law firms who are in the top 1 percent of all earners have seen their incomes rise faster than successful dentists who are in the top 10 percent. But by a similar margin C.E.O.s of large companies who are in the top 0.1 percent are seeing incomes rise faster than those law firm partners. Hedge fund managers in the top 0.01 percent are similarly outperforming the C.E.Os.

And the kind of people who can comfortably afford to pay a nine-figure sum for a Picasso, the top 0.001 percent, say, are doing still better than that.

The Washington Post commented on the recent $179 million Picasso sale:

This art market boom isn’t as pretty a picture as it seems, however. First, there are worries that it’s all a bubble that could burst at any moment. But then there are bigger concerns about the wider societal costs of such an inflated art scene.

The person who purchased Picasso’s masterpiece may be anonymous. But there are signs that we are all paying the price for such extravagant private auctions. Public museums can’t keep up with soaring prices. Now the magisterial “Women of Algiers” could disappear back into a dark mansion den or, even worse, a climate-controlled, tax-exempt airport warehouse until it has appreciated sufficiently in value.

The artist’s reception at the 79th Butler Midyear Exhibition at the Butler Institute of American Art is this Sunday afternoon. The collector who bought the painting and loaned it to the museum for the exhibition pointed out to me yesterday that they

The artist’s reception at the 79th Butler Midyear Exhibition at the Butler Institute of American Art is this Sunday afternoon. The collector who bought the painting and loaned it to the museum for the exhibition pointed out to me yesterday that they