Eve Mansdorf

Upstairs View, Eve Mansdorf, oil on linen, 26 x 30

the painting life

Hell, rising from a thousand thrones, oil on canvas, 77″ x 77″, Dolby Chadwick

Breakfast With Golden Raspberries, oil on linen, 22″ x 46″

I was humbly surprised to be informed recently that I’m a finalist for the Manifest Grand Jury Prize, with a cash award of $2,500, which will be bestowed on the best single work exhibited in the entire 13th season at Manifest Gallery. This means the organization’s panel picked Breakfast with Golden Raspberries as the best work in its particular exhibit earlier this year. The final award will involve the contribution of as many as 20 jurors and the few dozen works under consideration will have been culled from more than 15,000 entries to all of the Manifest shows throughout the past season.

Here’s a summary of the process from the notification:

Two Paint Cans, Wayne Thiebaud

More Thiebaud, on how he isn’t and was never a Pop artist, is self-taught, and doesn’t trust art that’s rooted in ideas, from another book published in the same year as the one in the last post, Realists at Work, John Arthur, Watson-Guptill, New York, 1983:

You’ve described yourself as a self-taught painter. Does that mean you didn’t study painting?

No. I started as a sign painter and did fashion illustration, furniture drawing, lettering, and cartooning without going to school. At twenty-eight or twenty-nine, when I went back to college, I got credit for most art courses by special examination by that time I had exhibits, Army experience, and so on. I have courses on my record showing I studied painting and drawing, but those were generally by challenge; they just gave me grades. I took art history, courses like the psychology of art, lots of art education courses, but no formal training.

I believe I saw your rows of pies in Life magazine in the early sixties. Your work kept getting linked with Pop Art at that time, which I thought was a bit of a distortion. Much of Pop Art relied on the look of mechanical processes and played down the effect of the hand.

If anything, my interest was the opposite, more out of the tradition of Velazquez, Manet, to Eakins, through people like Jasper John and Richard Diebenkorn, for whom the signature gesture is central.

When I painted the first row of pies, I can remember sitting and laughing—sort of a silly relief—“Now I have flipped out!” The one thing that allowed me to do that was having been a cartoonist. I did one and thought, “That’s really crazy, but no one is going to look at these things anyway, so what the heck.”

Some people have talked about the irony in my work and the idea terrifies me. That’s something I’m not interested in on a conscious level, and the reason I’m not is because that kind of explication of an idea vitiates its power. If I were using what intelligence I have to be ironic, I couldn’t be smart enough for myself. I would be disappointed, and I’m generally disappointed in irony for that very reason. It seems self-explanatory and anticipatory in a way that never interests me. The reason I don’t like classical surrealism if there is such a thing, is that it seems already to have arrived before you’ve seen it. Even a good painter like Magritte—his ideas put me off.

You may be opposed to irony, Wayne, but not to wit.

No, I think wit is a very high form of attainment. Any kind of wit is one of the toughest things to do. Also, it’s one of the things that’s missing in so much of the art world. When you lose the capacity for a sense of humor in an art form, you lose a sense of perspective.

I was just talking to Harry Rand, who wrote a book on Gorky, about how, when you get so you can do something, you don’t want to do it anymore, and he said, “Yeah, that’s very hard, but I think one of the things that painters have to learn is that it’s all right once in a while to shoot fish in a barrel.”

Art history in its essence is an organic, growing, and changing discipline. It’s more like a private game refuge, a treasure of exotic and wonderful rare Art Beasts. And our interests continue to change as we find out more and more. It’s hard for me to recognize something like progress or evolutionary development, say in a Darwinian sense, in the development of art. For instance, though I’ve conscientiously studied his paintings for many years, I just can’t find anything new, conceptually, in Paul Cezanne. For me he’s just a damn good painter, who’s using practically every device, convention, and trick in a painting, but he was so terrific, so bright, so careful in trying to be true to his relationships, that the painting is different, not because of any invention, despite his beliefs, but because of the composite structure and complexity of his perceptions translated into paintings.

–Wayne Thiebaud, from Art of the Real, edit. Mark Strand, Robert Hughes forward, Clarkson N. Potter, New York, 1983

In the fewest possible words, and his typically humble voice, Wayne Thiebaud here says nearly everything an artist needs to know about his or her relevance at any given place or time in the world of art. To wit: the historical sense of place and time don’t matter now. Everything is permitted; but only a few things are worthwhile. Thiebaud came to this realization after Arthur Danto did, but before Danto started talking much about it in 1995. By the 60s, when Thiebaud emerged by being mistakenly classified as a Pop artist, it became possible to do anything and call it art. There were no longer any limitations on what could be considered a work of art, something Duchamp asserted decades before, but it was a cynical declaration of freedom that didn’t flourish until the Pop artists adopted that same philosophical stance and liberated artists to do whatever they wished. The ironies embedded in Pop’s appropriations struck Danto as an integral part of the game, I think, but irony isn’t required and if anything it cheapens much of Pop and makes it far less interesting than it ought to be. (Don’t forget that Pop gave us Jim Dine.) It’s now entirely possible to paint like an Old Master without a postmodern smirk (some of Richter for example)—because the work has the same power now as it did hundreds of years ago. What Thiebaud is trying to say, and which remains difficult to articulate clearly, is that an authentic individuality matters more than any other consideration in art—and this individuality is infused into a painting subconsciously, not by choice. It’s about style, not stylization, as Susan Sontag said. Style is involuntary. A painting needs to be an extension, a replication not necessarily of something seen but of the wholeness of a painter’s identity, “the composite structure and complexity of his perceptions translated into paintings.” It has nothing to do with conceptual justifications or ideas or meanings and messages. A painting is more like a sacrament, a host for the life of the painter, than an expression of something a painter simply thinks up. It isn’t about thought, and it isn’t about hewing to anything but what an individual’s need to paint requires, which is something to be learned anew with each painting, something felt rather than known, discovered through act and instinct and a physical struggle with the qualities of paint.

Taffy #1, Oil on Linen, 46″ x 46″

Standing Taffy

This cairn of taffy squeezes

into shapes that Hammersley,

Stella, or Matisse

might have liked, loopy

curves of subtle tones,

color contained, simple as a tune

or cream uncoiling into a cup.

Stacked, unstable acrobats

lean, and come near

to teetering onto stone.

There’s a timid cheer

in their defeated smiles

that spiral through caramel,

raspberry and peach,

those fields of foggy color

wrapped in wax

and twist-tied into chipper bows.

Sweets, created to melt

into fleet flavors,

no one can respect,

nor put to use,

signifying nil but the need to please.

Dimpled, dented, crumpled,

they sag as if under more

than the punished bulk

of one (or two) of their own.

Those wings will never fly, guys,

but you’re serenely ready

in the purity of your hues

to stand for nothing but what you are.

Chevron Bowl, oil on linen, 12″ x 16″

I was pleased to learn that Minot State University purchased Chevron Bowl, which was included in Americas: All Media 2017. As a part of the school’s permanent collection it can be exhibited and also used as a teaching tool. It has always seemed that the school puts a special emphasis on printmaking exhibitions, so it seems appropriate that they wanted to hold onto this painting. It’s one of my best efforts in a more painterly approach to the process of making a picture, one in which I’m often thinking about the techniques of serigraphy. With all of my work now I apply a first layer of paint in discreet areas of uniform color, with an effort to establish the right value relationships between these flat shapes, so that the hue may be off here and there, but the image breaks down properly into lights and darks. Then I go to work within these sections of flat color, adding detail and tweaking color, both in my typical, painstakingly realistic work, and in less defined paintings like this one, where the effort is to work wet-on-wet, keeping the premier coup quality of the paint–and maintaining the sense of flat patterns established in the first application of paint.

In both processes I want to develop the painting in stages, keeping corrections to a minimum so that the color remains fresh and alive, yet with paintings like Chevron Bowl I want the ghost of flatness, as it were, to be an active element in the viewing experience. I want what the viewer sees in this work to waver just a bit between two and three dimensions. I want areas of color to remain as uniform as possible, which means I sacrifice precise, granular detail for the sake of preserving the evidence of my brush and hand. The execution becomes much simpler and the quality of light in a painting like this feels more delicate and resonant, the paint a bit less opaque. Because you’re not looking at something rendered with a sense of photographic accuracy, the mind is attending to both the paint itself and what the paint seduces your mind into seeing. In that conflict, the frisson of those two things–the image of the world I’m creating and the flat pattern of paint on cloth–I’m trying to bring a certain kind of life to the work different from what’s there in the verisimilitude of my more extremely realistic work.

Now that he lives in Oregon, instead of Western New York, I don’t get a chance to have coffee with Rick Harrington anymore, and I miss it. I think the last time I saw him was at his home and studio here, after he’d had his first surgery on his vocal chords. He used to be the loudest guy in the room; now he sounds more like Super Dave Osbourne leaning over to say something in a movie theater. His surgery saved his life, probably, but for a long, long time, the anesthesia dulled his brain in a way that made him wonder, as many of us do, about signs of early-onset something or other. But he’s come out of the fog and sounds like a new man. As he puts it here, he got lost in his mind. I thought I would pass this especially interesting and encouraging post, after a long silence:

OK, so it happened. I was warned, and didn’t act quickly enough. Nothing like a friend thinking maybe you’d died to get you off the dime.

A couple months ago we were in New York, on Long Island, visiting my marketing consultant. I’m her favorite pro-bono client, the sort of privilege you get when your daughter happens to be a spectacular designer. I’ve been futzing over a new logo/identity, which she usually lets me muddle through on my own until I go astray with type and such. Then she shepherds me back in, (i.e., takes over and gives me a file when she’s ready). Anyway, she pulled up my website to see where we were currently, (yeah, I know – wouldn’t you think she’d be current, checking in every few days?).

Dad! You haven’t posted anything since 2015! People are going to think you’re dead!

I gave her my best hangdog look.

Knock it off! You don’t get to use cancer! That’s history. Over. Time to move on!

I admitted I knew that, but was trying to worm my way out of my complete and utter negligence of the publicity side of my career. She got me to promise to get back to updating, to journaling, to keeping current.

But I didn’t. I thought a lot about it, but I didn’t do it. We lost my younger sister Cindy this year. If you knew Cindy, you’d think it impossible, something as puny as cancer taking her. But cancer’s not puny, and despite strength and courage unimaginable to me, to say nothing of a will way stronger than iron, Cindy is gone. The earth should have cracked at her passing, the universe should have split. But as loss so often is, it was quiet, leaving us all deflated and heartbroken. It’s taken some time for me to regain focus.

I have some vague recollection of posting a while back about habits, and how mine are nearly all bad. And over the past few years, since before 2015, I’ve gotten way out of the habit of posting anything, out of the habit of a lot of things.

So, I’ll catch you up, briefly. See if I can’t get a habit started again. Sometime a while back I was diagnosed with cancer in my vocal chord. If you’ve known me a long time, you’ll remember a voice that could really holler. I was loud. As a child I was asked by innumerable teachers to get everyone’s attention. In high school, the adorable little girls next door, Amy and Julie Hoffman, told their mother they were afraid of my brother Todd and me. They’re so loud, was their explanation. I could stop my dogs in their tracks at 400 yards, occasionally terrifying innocent bystanders (even some not so nearby) in the process. Yeah, that’s gone. But I’m still here. Two surgeries to extract the cancer, two more to rebuild my voice as much as my throat would allow, and then, once I was convinced I was going to live, I had my knee replaced. It would have seemed a waste of money otherwise.

And I lost my mind for a bit. Or more accurately, was kind of lost in it. I was unable to digest a book, paint well, and seemed to have suffered almost a complete loss of my sense of direction. I didn’t even know I had a sense of direction, I was just never really lost, comfortable still when others were sure I (we) was, or might have been, lost. A midnight paddle, for example, and portage and more paddling through the Adirondacks that left my brother-in-law a little fuzzy on how we’d arrived at our campsite. That sort of thing. But after my medical adventures, it was gone, along with the rest. And a few other oddities, skips of perception, etc. Finally after a couple of really strange and disconcerting episodes scared me to the doctor, my GP, my wonderful GP, ran a few tests and confirmed two things-

And the cancer seems to have been dealt with. When will my mind be my own again, I asked. Well, that’s a tough one, he said, (or something along those lines). You need to be active, to sweat a lot, to make your system circulate, and it will come back with time. But there’s really no telling how long it will take. A couple years. Maybe more. So get busy, he said, with life, with living. Don’t think about it.

Hard not to think about. And I’m hard headed. I was raised to work, so I kept painting. Poorly for a long while. They made beautiful flames when they burned.

I went to Alaska and ran a remote river with friends. I walked the dogs. A lot. Exercised. We welcomed an amazing granddaughter into the world. And after the kids gave me permission, I convinced Darby we should move back to the Pacific Northwest of my youth.

And then, seemingly in the blink of an eye, Darby got a job that really excited her, in Portland, OR, my home town. Next thing I knew, she was there working, we bought a house I hadn’t seen other than Zillow, and with the help of friends and family, we packed up a truck, loaded three cats and the White Devil into Darb’s truck, Uly in the cab with Todd and me, and off we went to Oregon City, OR. A trip we all swore we’d never do again, but I knew I had to repeat it a few months later with the rest of our stuff, with my buddy Paul Driscoll along as co-pilot.

Damn. What a pain in the ass. Seriously. But we’re here now, and I love Oregon as much as I did when I was a kid. More for all the years of missing it. The whole place is new to me again, and I hope to explore it until I drop, 35 or 40 years from now. Rivers to run, mountains and coast to hike, and steelhead to chase. At least that’s the plan. I’m not new to the idea of plans going awry, of punches to the head, but I’m making plans anyway.

And granddaughter No. 1 has been joined by a little sister, and a cousin. That’s the downside of the move – them so far away. But it’s actually quicker to fly back and see them than the drive was. And I don’t have to drive through New Jersey traffic. And the other part of this plan is grandma and grandpa’s ultimate summer camp. Hiking, horses, rivers, rafting, paddling, ocean…. they’re not going to want to go home. And until they get out here, or if they don’t, we’ll be back there frequently.

So out of the blue, I get a call the other day. I didn’t recognize the number, and didn’t answer. But there was a message, and it’s from an old fishing buddy- like way back old, college days. I call him back, we catch up a little, and he said, Yeah, I was on your website, and I saw that you hadn’t posted since June of 2015. I was afraid you were dead.

So this is the first attempt at re-establishing the habit. To let you all know, I’m not dead. There are a few updates tucked in here, on the Artist Statement page. And the painting above. I’ve been working a lot, with a bunch of pieces finally coming together. More soon. I think. If not, Emily, give me a swift kick this time. I can’t have anyone else thinking I’m gone.

ps- (do blog posts have ps’s?)- This spring, something has cleared out more of the cobwebs. I suddenly have more ideas than I can keep track of. Like it was pre-cancer. I have some summer travel in between, but I’ve got to find a larger studio this fall. So much to do. Big stuff. Stuff I’m really excited about. I’ll try to remember to keep you all in the loop.

So, if you’ve read this far, I need to say Ive migrated the Field Notes to my new website- the one I got scolded for not updating. I’ll post here a few more times, but at some point it will all be over there. It can be found at: http://www.richardcharrington.com/field-notes/

It’s tin man hands. And it’s a good look. If Goldfinger had been named after a different precious metal, his victims might have had this kind of shine, only all-over. These are Mandi Antonucci‘s fingers, after kneading a lump of graphite putty to coat them thoroughly enough to do some experimental finger-drawing. Her drawings, which employ some of the techniques of optical illusion Escher used, seem to be more Jungian snapshots of her psychic history and personal struggles than his cerebral studies in recursive visual structures. One of her psychological self-portraits is endearingly entitled Daydream Believer, in a nod to The Monkees, beloved by her mother who turned Antonucci into a devotee as well, after overhearing Davy Jones sing his tunes to those Wrecking Crew arrangements so many times. Her interesting, accomplished work can be seen now at Maker’s Gallery.

It’s tin man hands. And it’s a good look. If Goldfinger had been named after a different precious metal, his victims might have had this kind of shine, only all-over. These are Mandi Antonucci‘s fingers, after kneading a lump of graphite putty to coat them thoroughly enough to do some experimental finger-drawing. Her drawings, which employ some of the techniques of optical illusion Escher used, seem to be more Jungian snapshots of her psychic history and personal struggles than his cerebral studies in recursive visual structures. One of her psychological self-portraits is endearingly entitled Daydream Believer, in a nod to The Monkees, beloved by her mother who turned Antonucci into a devotee as well, after overhearing Davy Jones sing his tunes to those Wrecking Crew arrangements so many times. Her interesting, accomplished work can be seen now at Maker’s Gallery.

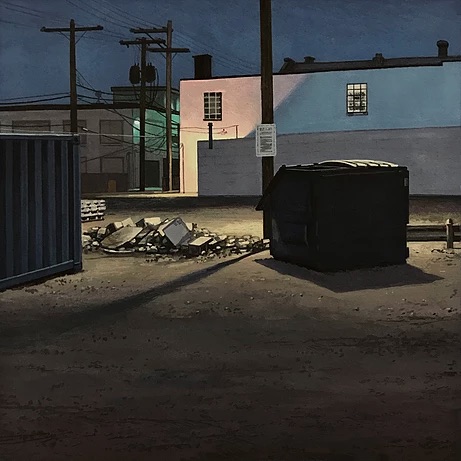

Thanksgiving Day, Linden Frederick

I discovered Linden Frederick only last year, on a visit to Forum Gallery, where they are especially proud to represent him, judging by the conversation I had there. It’s impossible not to love his work, as precise as any photorealist’s but full of humble, wistful emotion about human life, unlike so much of the strangely cold hyper-realism that prevails in the commercial art world. It’s no wonder that he’s the darling of writers as diverse as Ann Patchett and Richard Russo (Frederick’s world looks like an exhaustive slide show of homes and hangouts in one of Russo’s towns). The Center for Maine Contemporary Art has a show up now, a sort of team effort among all Frederick’s literati fans, where they have brought their own narratives to the paintings he’s done, fabricating stories around his still images. It’s a fabulous idea for a show, which I would have named Bring Your Own Narrative. Here’s the esteemed roster:

Anthony Doerr (All the Light We Cannot See)

Andre Dubus III (House of Sand and Fog)

Louise Erdrich (The Round House)

Joshua Ferris (Then We Came to the End)

Tess Gerritsen (Rizzoli & Isles series)

Lawrence Kasdan (Raiders of the Lost Ark)

Lily King (Euphoria)

Dennis Lehane (Mystic River, The Wire)

Lois Lowry (The Giver)

Ann Patchett (Bel Canto)

Luanne Rice (Crazy in Love)

Richard Russo (Empire Falls)

Elizabeth Strout (Olive Kitteridge)

Ted Tally (The Silence of the Lambs)

Daniel Woodrell (Winter’s Bone)

In clicking around Frederick’s site, I discovered you can order giclee prints of his work, for a few hundred dollars apiece. It’s heartening to see an accomplished, successful artist of his stature doing this, despite the long-standing prejudice against these prints in the art world–partly because many lesser galleries push them as if they were the equivalent of woodblocks, serigraphs or lithographs. They aren’t, but in my view, reproductions like these serve as a genuine way to connect with people who love the work but can’t afford the original. Offering reproductions on archival paper this way ought to become commonplace. In this economy, the people who would identify the most with the world Frederick depicts could hardly afford one of his actual paintings: there’s a sort of justice in making the next-best-thing available to at least some of them. Real recognize real, as they say.

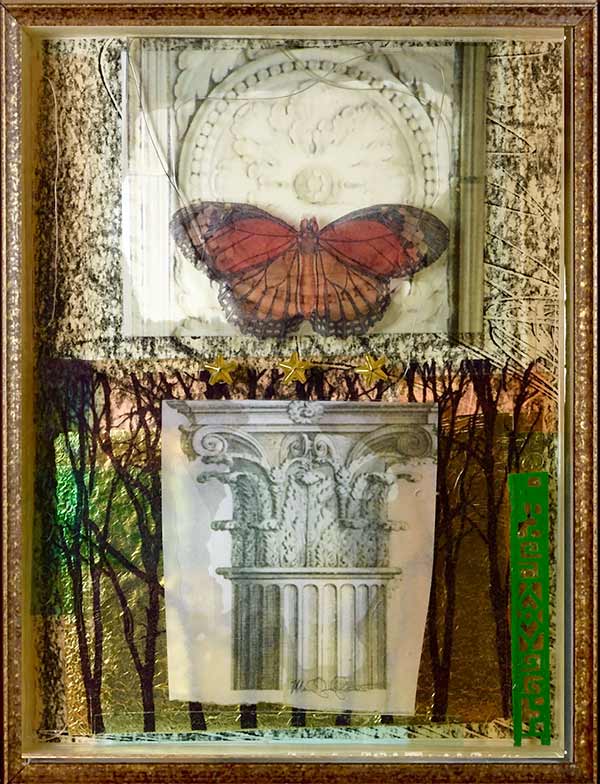

Monarch 3, Margery Pearl Gurnett

Jim Hall wrote such a fine essay about work on view now at Oxford Gallery, by Margery Pearl Gurnett, along with some fine still lifes by Patricia Tribastone, It helped me understand why I like her work, so I’m sharing it here:

Probably no concept is more fundamental to the Post-Modern aesthetic than that of “appropriation”: the reuse of images and materials borrowed from other sources. And no concept has generated more controversy. The amalgamation of historical images by contemporary artists like Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer has been lauded as complex social and cultural commentaries. The wholesale “borrowings” by artists like Richard Prince, on the other hand, have attracted charges of plagiarism and sparked numerous legal actions. The task confronting art critics and historians, copyright lawyers, and cultural anthropologists, therefore, is one of differentiating between the legitimate and the illegitimate uses of “appropriation,” and the idea that continually emerges in this discussion is that of “recontextualization.” Simply stated, “recontextualization” refers to the manner and extent to which materials borrowed from one context are reconfigured in a different context to assume different signification.

A fine example of “recontextualization” is the work of Margery Pearl Gurnett. Gurnett appropriates images from a variety of sources, including many of her own creation, incorporating them in new contexts with different significations. And the means by which this “recontextualization” is accomplished is glass. Layering semi-transparent image upon image under thin panes of transparent glass, the artist creates a composite image in which several images are perceived literally through each other. Perceiving the images simultaneously rather than serially changes the temporal dimension with which we apprehend them. In a traditional painting or collage, the eye moves over the flat surface reading each image or part of an image in sequence. In Gurnett’s work, the composite image is apprehended at once and seems to resonate with associations and multiple levels of meaning.

A motif which appears in various forms in many of Gurnett’s pieces seems to suggest the non-linear way in which her images work: the spiral or helix. MORE

Katie, Mike Tarantelli

You have a couple more weeks to see a marvelous invitational show at Main Street Arts. It includes work from eight artists working in the Rochester/Finger Lakes region. The work is consistently great and often surprising in a way that makes you keep coming back to look at many of the paintings. I’m proud of the work of a few of my friends in this one: Tom Insalaco’s consistently mysterious and usually dark portraits and figures in his contemporary baroque style; Jim Mott’s night paintings, brilliant, quickly executed grisaille studies full of feeling for nature and a hint of spirituality; and Chris Baker’s increasingly masterful gouaches from Scotland and many other places. One of his paintings, Skye, below, was my favorite in the show, and I’m eager to see his two-person show with Jean Stephens at Oxford Gallery soon. Kurt Moyer’s big representation of a forest floor works as all-over abstract, the way some of Welliver’s denser forest interiors do, with a sumptuously handled surface. Mike Tarantelli’s small portraits reminded me of early Lucien Freud before he started troweling on the paint like a possessed mason in his signature way, back when he was doing those ultra-sharp faces and figures, whose precision looked almost imaginary. There’s also great work from Belinda Bryce, Lacey McKinney, and Sarah Sutton. Everything is fresh and sometimes startling in its immediacy. I love Main Street Arts. It’s a good friendly space, bright, with big storefront windows and plenty of room for larger work and fresh intelligence in its curating. The show ends Oct. 6.

Skye, Chris Baker

Construction Lot Nocturne, Gouache on paper, 8″ x 8″

There’s another week left in a show of small works by Christopher Burke, in Columbus, Ohio, at Brandt-Roberts. These carefully constructed urban nightscapes often have a dumpster or trash receptacle serving as fulcrum for everything else in the picture. In his choice of subjects, Burke has taken to heart Charles Hawthorne’s advice to go paint the train station. He paints the spot few others would stop to appreciate and makes it a source of pleasure. These paintings remind me of a variety of other work, in the best way possible–he’s assimilated his influences without being derivative. Matthew Cornell’s show not long ago at Arcadia, when it was still located in downtown Manhattan, depicted maybe a slightly earlier hour of twilight that bathed his assiduously realistic paintings of homes he’d inhabited throughout his life. As do Linden Frederick’s popular scenes of dusk. Burke favors the same crepuscular glow, the sky slipping into sleep mode, with artificial lamps already burning in back streets. Yet his images are astringent, abstracted and minimal, structured into grids of crisply delineated form. His palette is severely disciplined, pared down to a very basic range of hues, both in these and his usual oils of buildings in the daylight hours. Yet the emotion these gouaches evoke works like a faintly heard melody, their soft illumination pushing back against the quiet emptiness of deserted alleys and streets. Sometimes one of the skies in these paintings on paper suggests the light of the city itself shining up and then banking down off the clouds. It’s the light you see and love along with the bittersweet ache of solitude when walking home from a pub, with more than a bit of a buzz, at 2 a.m. (Those were the days.) It’s a world without human figures, everyone inside or else on the other side of town, a few windows shining with hints of routine domestic mysteries hidden behind those walls. What I love most about this series are his dumpsters and trash bins, the least picturesque subject one could pick at that hour, loved only by those who search for ways to survive another day by diving into them. The night gives Burke the ability to push his geometric bent even further toward abstraction in the way light falls and the shadows cut on the bias across a wall. There’s nothing here with a dimension larger than 16 inches and the smallest painting is 5″ x 7″, which is miniature to me, and yet the scale doesn’t diminish his ability to suggest detail and give his scenes the crisp definition reminiscent of Sheeler’s more representational paintings. But his mood is closer to Hopper, and even to the American Scene paintings from his fellow buckeye, Burchfield. Amazingly, he not only has this solo show of more than twenty paintings up now in Columbus, his two-person show in Chelsea at George Billis will open on Nov. 7.

A reminder from Manifest:

THE 8th ANNUAL MANIFEST PRIZE

$5,000 Cash Award + Solo Feature Exhibit of the ONE Prize-winning work

Deadline: October 1, 2017

In 2015 we were excited to announce that the annual Manifest Prize (ONE) award was increasing to $5,000. This concretely underscored our non-profit organization’s strong desire to reward, showcase, celebrate, and document exceptional artwork being made today, and to do this in a tasteful non-commercial yet very public way. Further, the Manifest Prize is intended to incentivize and support the creation of excellent work into the future. Manifest’s mission is centered on championing the importance of quality in visual art. This project is one aspect of the realization of that mission and we are happy our board of directors has approved the continuation of the significant award amount.

The entry process for the 8th annual Manifest Prize award (and ONE exhibit) is now open.

Open to works of any media, any genre/style, any size…

There are no restrictions on submissions to The Manifest Prize. Artists who have submitted to or been included in previous Manifest projects are welcome to submit to any future project, including the Manifest Prize.

Works submitted must have been completed within the past five years (2012-2017 for the 8th Manifest Prize).

IMPORTANT! Works submitted MUST be available for the exhibition period of early December through mid-January in order to be eligible for the prize. Submission constitutes a formal agreement to provide the work for exhibit should it be selected.

Jury Process: Manifest’s normal selection process involves a complex two-part system. This exhibit will be juried by an anonymous 7-15 member panel of professional and academic advisors with a broad range of expertise from across the United States. Because of the nature of this project, works approved by the first jury will be passed through a second, and possibly a third jury round, with jurors being shuffled from round to round. The work receiving the highest average score will be awarded the prize. The ten next highest scoring works will be the semi-finalists. Juror comments will be posted in the gallery and in the Manifest Exhibition Annual publication.

In addition to the cash prize and solo feature gallery exhibit at Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati, the prizewinner will have multiple pages devoted to their winning work in the season-documenting Manifest Exhibition Annual (MEA) hardcover publication, including artist’s statement, bio, and jury statements. The ten semi-finalist works will be included in the MEA as well.

Submission deadline: October 1st of each year

http://www.manifestgallery.

The economy has been stagnant for the vast majority of people for decades now—wages have stalled since the mid-70s, as profits and productivity have never stopped climbing. This long-term decline has been disguised by the dot.com mania and the real estate bubble, and the current, overheated stock market. As people point to traditional, superficial indicators of growth, and the media fails to explore what’s actually happening economically for most people. This makes it hard to connect the dots and understand why many galleries are struggling and some going under. It seems only the wealthiest have money to spend on art, and most of it is going to the highest end—in other words, the “brand” mentality governs spending, with people buying work at higher-priced work that seems more assured of rising in value. The dubious assumption behind all this is that the current art market actually prices work according to its actual value as art rather than as a predictable investment.

Nan Miller recently announced she was finally, really, closing her gallery here in Rochester, NY, after years of appearing to be going out of business and selling work accordingly. For years now, the Oxford Gallery, where I exhibit, has been offering work at a discount during the summer in order to stimulate sales, and Jim Hall’s inventory of 19th century American art has become more difficult to sell in recent years. None of this has to do with the quality of the work itself.

Bill Santelli and I were discussing all this yesterday when he got a notice of yet another gallery closing in Europe: “Freymond-Guth, the art gallery founded by Jean-Claude Freymond-Guth in Zürich in 2008, is abruptly closing (after being) named as one of 11 young dealers revitalizing their local art scenes earlier this summer.”

The site published a farewell letter sent to the owner’s mailing list. Here are excerpts:

Much has been said about how the art world has changed in the last years. I will not repeat it here. The consequences for art in an increasingly polarizing society ultimately built on power, finance and exclusion are clear. What I would like to address though . . . is a sentiment (best) described as alienation. Alienation in all relationships between all participants. Alienation in a climate where space and time for reflection, discussion and personal identification with form and content of contemporary art have become incompatible with the ever growing demand in constant, global participation, production and competition. MORE

Selfie, oil on panel, 12 x 12

My recent self-portrait, premier coup mode, will be in the upcoming invitational exhibit at Viridian Artists, “Selfies & Self-Portraits: 21st Century Artists See Themselves.” Sept. 5-30. Between my current effort and the next painting I hope to do a small series of faces in a similar way, on thick MDF panels, as this one was done.

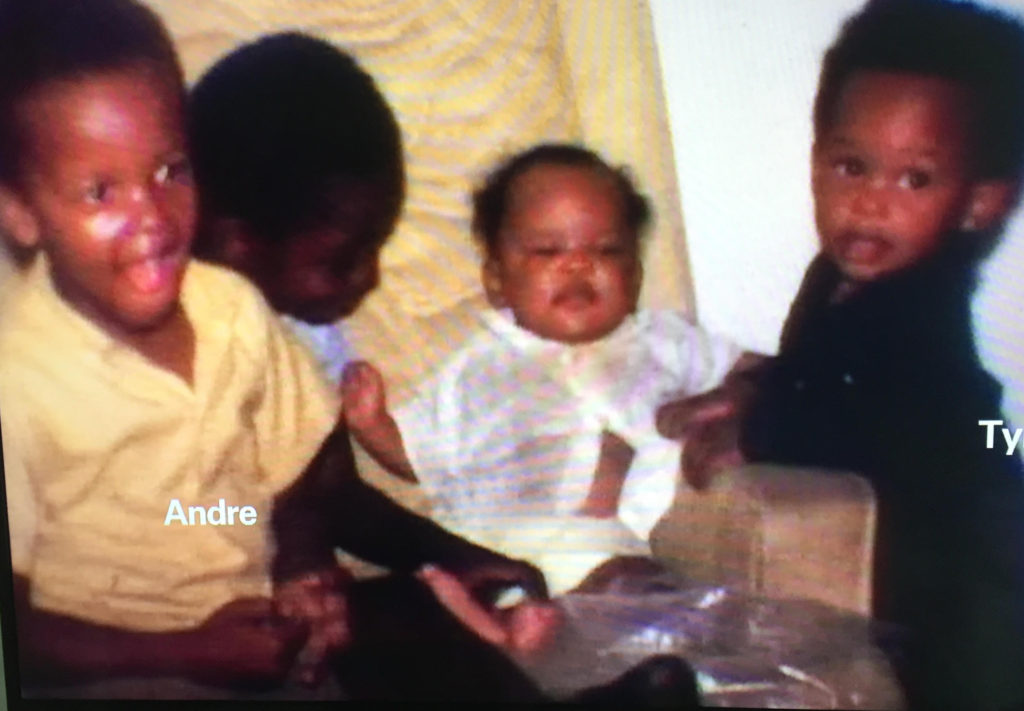

Andre Young, aka Dr. Dre, and his brother Tyree, far right

The The Defiant Ones on HBO is a stirring documentary that made the hair on my arms stand up, exactly the way Dr. Dre got “goosechills” on camera as he remixed a favorite track from the past. The show humanizes this billionaire rapper in a way I haven’t seen since I spotted the snapshot of Nas when he was seven on the cover of Illmatic. That moment in the documentary, with Dre in thrall to a song from his past and the hair prickling on his arms, reveals the endearing nerd, the Dennis Wilson-obsessive, inside Dre—and, even moreso, within his business partner, Jimmy Iovine. An inner nerd drove each of them to the success they enjoy. Iovine’s incessant, fanatical, round-the-clock pursuit of production excellence resulted in a string of incredible career breaks as the skinny brilliant studio rat adjusting the mixer for John Lennon, Foghat, Bruce Springsteen, and Patti Smith, all of that just a launching pad for the success that followed. He and Dre both had the drive of Miles Teller’s character in Whiplash: a kind of zombie apprenticeship to an insatiable talent.

My first taste of Dre was his work with Snoop Dogg on Doggystyle. That mashup of funk and hiphop into a nasty celebration of gangster pleasures reminded me immediately of my forgotten delights in Johnny Guitar Watson back in the 70s. In both cases, funk and G funk, it was fun transgression, the way rock had once been a slightly forbidden pleasure. You knew it was just wrong, as it made you grin. Tipper Gore aside—remember her campaign against all of the foul language?–if you’re rapping, you can pretty much get away with anything. All is permitted, and so we’re free to enjoy all that badness vicariously, a musical day off from your own well-behaved boogie life. Along with Nirvana, it felt like a cure for everything that had happened to music in the 80s other than the rest of the bands that emerged out of punk.

Hiphop had been keeping alive the worship of a certain kind of beat that MORE

Jim Mott paid a visit last week and we talked for a couple hours, as he sat in one of our Adirondack chairs and sketched a bit of what he saw in the yard, probably some of the birds attracted to our feeders. He was wearing a Red Sox cap someone had left in his car once, and was in a good mood, thanks to the fact that he has a job working with a nature conservation group to supplement whatever he makes from his art. Most of the time, Jim trades his paintings for room and board, when he’s in his Itinerant Artist mode, but he also sells and has a show coming up with several other regional artists. It was a good conversation, and here is some of it:

JM: On those rare cases when I sit down and really draw something it’s so refreshing but it’s hard to make myself do it. I do a sketch and think maybe I’ll do a painting from it and then I see everyone else holding up their phone cameras. Working from sketches, we’d be doing art the way we did it thirty or forty years ago. Richter certainly relies on photography.

DD: Richter’s name has come up a lot in the past few days. I was just emailing with Rick Harrington who was talking about how he’s been watching Richter’s videos. And I was emailing this morning with Bill Stephens and Bill Santelli and we were talking a little about Richter.

He does those big squeegee paintings which I really like.

I do too.

I saw some of his photo-real paintings in Chicago.

We talked about that.

Up close the presence of the paint is so sublime.

I think he focuses a lot on the quality of the surface. I think he’s looking to Vermeer and Old Masters for the photorealistic paintings. He gets that very soft edge.

But what makes the paint feel so there is that there’s such a sense of material. Its like the feel of something done with limestone.

Rick and I have talked about our disappointment with Walton Ford’s paint. You stand back and it’s one hell of an image and it really works, but the love of the paint doesn’t seem to be there. You can see the paint and it’s very evident; it’s a jumble of paint up close but it doesn’t have that quality you’re talking about. But it works.

This is a distraction but you’ve probably seen this book. (Jim handed me a coffee table book he’d brought with him, a catalog of George W. Bush’s portraits of war veterans.) MORE

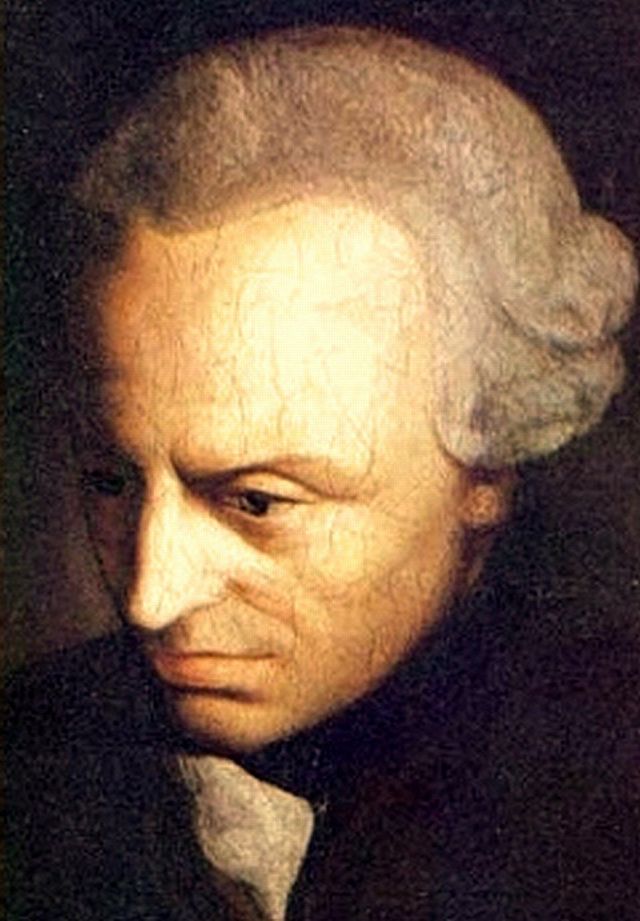

Kant

In the The Sublime and the Beautiful Revisited, Iris Murdoch rexamines an aesthetic distinction that most people would associate with Edmund Burke—how what is beautiful and what is sublime occupy completely different modes of human experience. Her subject is Kant, though, and Kant presented Burke’s distinction in a slightly different way. For Kant, art creates a beautiful object, worthy in and of itself. A painting doesn’t instruct, or serve any purpose at all, but is a self-justifying object where human imagination and understanding come together in harmony. A work of art, by definition, has to be entirely intelligible, in this view—or, rather, its value resides in its intelligibility, even though it has nothing specific to say. It just is, and that’s enough, the way things in the world are what they are and are nothing else—and you recognize and appreciate it immediately for what it is, as you would a flower or a vase. It is what it is, transparently beautiful, and that’s quite enough. Kant isn’t interested in what doesn’t surrender to reason—reason equals freedom equals virtue. Moral choice for him was the exercise of reason, cutting through the murk and mess of individual human experience and emotion, facing toward what was universal and just plain reasonable, so that the individual could act on that knowledge. Beauty, in art, is the experience of seeing a hint of this order, this understanding, shine forth from something created.

With the sublime on the other hand, Kant follows Burke’s earlier distinction: it is an experience of the tension between reason and what’s beyond its grasp, the threatening mystery and magnitude of nature. In that confrontation between understanding and what resists reason, intransigent and hostile and overpowering, there was a thrill in which a human being feels gratified at being free of that threat, of being guided by the “dignity of reason” in the face of the inaccessible and inhuman snow-covered Alpine peak. Half a century later Melville felt only dread, even horror, at the whiteness of the whale—inscrutable, blank, pitiless, and alien. (That shift, the rise of dread and despair, in Melville and Kierkegaard and Nietzsche–and I suppose you could go on indefinitely with other figures, Munch and the expressionists and so on—would seem the most significant development in 19th century culture, emptying out into the angst and nausea of the existentialists.) Kant would have smiled with bemusement at Melville’s anxiety: Herman! Buddy! You’re troubled by the color white, sailor? Really? A color? For Kant, humanity transcends nature because we can establish and affirm what is intelligible and therefore superior to the opacity of the natural world, and thus exercise our freedom from it and give it meaning—which sounds very much like an apology for what we are now doing in science and technology and nearly everywhere else in our postmodern realm. We’re remodeling the unsatisfactory natural world, to our liking, along with human nature itself, as the genetic code becomes our sandbox. Good luck with that.

Murdoch takes Kant’s idea of the sublime, though, and brings it down to earth—what replaces the implacable and opaque in nature becomes, for Murdoch, the other human being. The woman in the seat next to you on the flight is just as stubbornly resistant to human will, and just as confounding to one’s solitary comfort as the vast silence of the starry sky. And yet with the passenger staking her claim to both armrests in 13A, you have a choice to make: you can tolerate and understand her or you can hate her. There’s no avoiding her, unfortunately. Loving her is probably out of the question, unless it’s a flight from New York to Sydney and the conversation takes a novel turn. By contrast, the Alps don’t care how you feel about them. She takes Kant’s acknowledgement of the way in which the world resists understanding and turns it into a certain kind of attention and the moral choice that can flow from it. For her—her essay was published in 1959—what Kant saw in the individual’s uneasy relationship with nature’s power transfers directly into what’s missing in contemporary art, especially fiction. For her, most fiction, and by implication other art forms, avoids this uneasy apprehension inherent in Kant’s notion of the sublime when applied to other people. What gets written is either a self-absorbed elaboration of the author’s own experience or obsessions—stripped down into mythic form—The Stranger or The Catcher in the Rye—or else it’s a thin journalistic/political account of contemporary life, full of verisimilitude, with characters that serve whatever predetermined purpose the novelist has in mind for them. Given that choice, she prefers, say, the pointlessness of The Catcher in the Rye. Yet, for her, the greatest novelists, such as Tolstoy, created a world populated by characters whose reality vastly exceeded whatever purpose they could have served for the writer—they demonstrated that the author succeeded in the heroic effort to forget himself by imagining, making real, other human beings completely distinct from the author’s personality. Their reality was the achievement, not anything the author wanted to say by making them real. And this is the heart of Murdoch’s entire philosophy: a human being’s greatest progress in realizing what is good comes as a consequence of being intensely aware of anything other than the self, but best of all, other human beings. That effortful awareness makes love possible. And one of the ways this love can manifest itself is by creating art—the most powerfully moral form of art being fiction. Updike criticized J.D. Salinger for loving his characters more than God loves them, but Murdoch would say there is no such thing as loving one’s fictional creations too much, as long as they aren’t just your avatars.

For her, George Eliot and Tolstoy and Jane Austen, were the masters of this self-effacement—Shakespeare even more so, as a playwright. She moves back and forth between philosophy and fiction/art, pointing out that you can find the same dichotomy among the philosophers, like Sartre and even Kierkegaard, on one side—the spiritually solipsistic freedom of the individual wrestling with God or just the contingency of life—and the linguistic philosophers like G.E. Moore or Wittgenstein, who seem to simplify all agonized moral choice by ironing out the various meanings of the word “good” in ordinary human language. (Admirably she gets through the entire essay without ever quoting Sartre’s famous “hell is other people.”) Define your terms and the way becomes clear; simply figure out what the “good” means in any given usage of the word and then do it. She doesn’t put it that simplistically, but makes it sound just about that dry and lifeless and easy. To know what’s right will lead to doing it—that idea goes back to Socrates. For her, in this choice between what she recognized as the two dominant modes of philosophy, what got lost was the problem of other people, all of those beings who exist and have needs beyond the boundaries of the thinker’s head and whose behavior creates dilemmas that can’t be solved by thinking about them, or making choices, in isolation. And doing what’s right, even when you know it, is generally a challenge for nearly everyone. And this is precisely what was getting lost, in her view, in fiction—the necessity of getting to know people who are completely different from you and wrestling with the demands for attention they place upon you, demands for sympathy, for action. For Murdoch, the art of the novel peaked with George Eliot and Anna Karenina and then began to decline.

Hers is an intensely moral vision of life. So it’s no wonder that the person who is missing in all this—a novelist she so strenuously avoids mentioning—is Proust. In Proust it all comes together in a way she probably wasn’t able to acknowledge—mostly because in Proust, as in Heidegger (whom she didn’t grapple with until it was too late in her career), an explicit concern with morality is almost entirely absent. Proust improvised an astonishingly complex social world from his own experience while obsessively examining a kaleidoscope of subjective, finely-calibrated emotional experiences—a fractal vortex of internal states (mostly having to do with sexual jealousy) of mind and heart. For Camus, Proust was the best example of the ideal of the artist who refuses the intellectual/philosophical extremes—he explores the rain forest of his own inner life and the inner life of others without ever going so far as to become a surrealist, and he constructs a beehive of human beings around his narrator, who give the reader a sense of the real, actual, objective world, though his approach never becomes journalistic. He embraces a poetic and yet exhaustively observant Middle Way. His characters are probably the most complex creations in all of fiction since Hamlet. But there is no moral dimension to his world—Harold Bloom puts him almost in a class by himself in Western literature, linking him to the Hindu sages, having recognized some fundamental unity in the good and bad, life and death. He looks past it entirely and gives to his characters his dispassionate and tolerant and inexhaustible curiosity and delighted awe—as if each human being, no matter how depraved or perverse or silly and shallow or great and admirable, were equivalent to a work of art so fascinatingly intricate and integrated that to pass any sort of moral judgment on his or her behavior would overlook that character’s marvelous complexity. The rain of his rapt attention falls on each of them, the just and the unjust, in equal measure. In a way, Proust sees people with the same detached but avid delight that a collector of insects brings to his display case, and yet he’s anything but detached about human life—the slippery, fluctuating continuum of feeling and intuition are almost all that matter in his world. It’s his medium. What’s diminished in Proust isn’t just the moral dimension, but love which is more than erotic compulsion or emotional dependency. As Bloom points out, the only real love in the novel is evident mostly in the narrator’s relationship with his mother and grandmother. To say the least, his vision lacks a certain friendly warmth, and so I think Murdoch, whose philosophy is all but Christian—a sort of gospel of goodness and love without God—had to avoid grappling with this figure who did exactly what she required by creating a multitude of unpredictable, living human beings, each dramatically distinct and independent from the author himself. He has no designs on them, they are allowed to be simply what they are, the sprawling mess of their behavior seeping like colors of the rainbow throughout hundreds and hundreds of pages, free to do whatever they most naturally do, because the huge novel is orchestrated almost without a plot. The problem for her had to be that Proust didn’t recognize the significance of moral choice—we are what we are, and it’s a marvel, for better or worse. He was a mystic for whom paradise is everywhere, in all the minute particulars of the world around him—completely out of reach to his purposeful, everyday (and moral) mind, but present everywhere in the pages of his book. Proust’s creative relationship to the world is, for me, identical with a great painter’s who presents the world–his or her world–just as it is, for its own sake, without any agenda or purpose other than to make it alive and real.

A detail of Summer Storm by Jean K. Stephens, one of many great paintings on view at Oxford Gallery in the summer show.

A detail of Summer Storm by Jean K. Stephens, one of many great paintings on view at Oxford Gallery in the summer show.