Doppleganger

Work in progress from Bill Santelli, for the upcoming Doppleganger group show at Oxford Gallery. I’m half done with my offering for the show, and the undone half is making me nervous. Maybe that’s fitting, given the theme.

the painting life

Work in progress from Bill Santelli, for the upcoming Doppleganger group show at Oxford Gallery. I’m half done with my offering for the show, and the undone half is making me nervous. Maybe that’s fitting, given the theme.

Piero della Francesca, Madonna and Child with Saints, Brera

The hardest task in life is to know yourself. In his essay on Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection, which Huxley called the greatest picture in the world, he makes this astute observation, but he saves his greatest wisdom until the end. The last sentence should be tacked to the wall of every painter’s studio:

“Is Fra Angelico a better artist than Rubens? Such questions, you insist, are meaningless. It is all a matter of personal taste. And up to a point this is true. But there does exist, none the less, an absolute standard of artistic merit. And it is a standard which is in the last resort a moral one. Whether a work of art is good or bad depends entirely on the quality of the character which expresses itself in the work. Not that all virtuous men are good artists, nor all artists conventionally virtuous. Longfellow was a bad poet, while Beethoven’s dealings with his publishers were frankly dishonorable. But one can be dishonorable towards one’s publishers and yet preserve the kind of virtue that is necessary to a good artist. That virtue is the virtue of integrity, of honesty towards oneself. Bad art is of two sorts: that which is merely dull, stupid and incompetent, the negatively bad; and the positively bad, which is a lie and a sham. Very often the lie is so well told that almost every one is taken in by it–for a time. In the end, however, lies are always found out. Fashion changes, the public learns to look with a different focus and, where a little while ago it saw an admirable work which actually moved the emotions, it now sees a sham. In the history of the arts we find innumerable shams of this kind, once taken as genuine, now seen to be false. The very names of most of them are now forgotten. Still, a dim rumor that Ossian once was read, that Bulwer was thought a great novelist and ‘Festus’ Bailey a mighty poet still faintly reverberates. Their counterparts are busily earning praise and money at the present day. I often wonder if I am one of them. It is impossible to know. For one can be an artistic swindler without meaning to cheat and in the teeth of the most ardent desire to be honest.”

–Aldous Huxley, “The Best Picture”, 1925, from The Piero Della Francesca Trail, John Pope-Hennessy, 1991

Reading this passage recently offered me a slightly different way to think about the title of Houellebecq’s latest and more compelling novel, Submission. The word “difficult” here worked like a droll, understated punch line, which is how most of the wit works in Houellebecq. From The Map and the Territory, Michel Houellebecq:

Many years later, when he had become famous—extremely famous, truth be told—Jed would be asked numerous times what it meant, in his eyes, to be an artist. He would find nothing very interesting or original to say, except one thing, which he would consequently repeat in each interview: to be an artist, in his view, was above all to be someone submissive. Someone who submitted himself to mysterious, unpredictable messages, that you would be led, for want of a better word and in the absence of any religious belief, to describe as intuitions, messages which nonetheless commanded you in an imperious and categorical manner, without leaving the slightest possibility of escape—except by losing any notion of integrity and self-respect. These messages could involve destroying a work, or even an entire body of work, to set off in a radically new direction, or even occasionally no direction at all, without having any project at all, or the slightest hope of continuing. It was thus, and only thus, that the artist’s condition could, sometimes, be described as difficult.

Last week, two days before the Inauguration, I somehow managed to fly into Washington D.C. and then back home the same afternoon without seeing any signs that our new President was about to ascend to his office. It was an uninterrupted ride from Dulles to Embassy Row, near Georgetown, where I had a meeting with one of Eastern Europe’s ambassadors to the U.S. to talk briefly about working with him on a book project. But our lunch plans were interrupted by a delegation of his countrymen who were insisting on attending the Inauguration. While he attended to his guests, I was happy to amuse myself for an hour before we were able to meet. His administrative assistant was incredibly solicitous and offered to keep me company until he was able to return, but instead I wandered around Embassy Row, had a quick salad at Pizzeria Paradiso on Dupont Circle and then realized the Phillips Collection was a couple blocks away.

It had been years since I’d visited the Phillips, which I recalled as one of the best art-viewing days of my life, the permanent collection was so good. I was able to spend only about twenty minutes there this time, most of which I invested in the rooms where the institution’s large holding of Jake Berthot’s paintings was temporarily on view. I moved quickly past the earlier paintings until I came upon a fairly recent one of a lone bare tree. At first sight, it was remarkable, and the longer I stood before it, the more it offered up–I’m repeating an observation that has been made before about his work, that after long viewing what you see in his work becomes increasingly rich and subtle. His work ranged from nearly pure abstraction to his minimal, often Turneresque evocations of the natural world around his Catskill studio. His engagement with heavily-layered paint brought to mind Stanley Lewis and even Auerbach, though Berthot’s accretion of thick oil feels more tranquil. There’s a dark serenity in his images, a truce–or perhaps a productive trade agreement–with mortality. His work resonates more with the Taoist void, a sense that form in nature rises up out of something inexpressible and inchoate, but intensely alive. Even in that very short window of time, I felt I’d discovered work both remarkable and masterful. A very serendipitous encounter, thanks actually to Google Maps, which–when I routed my walk back to the embassy–had helpfully pointed out that the Phillips was only a short walk from the bar where I was finishing lunch, and only a block from my appointment.

Hyperallergic interviewed Berthot a few years ago, not long before he died, and it was a revealing conversation. He was mostly self taught, though he did some coursework in his youth, and over the years he groped toward his final approach in fits and starts. For a while, early in his career, he found himself doing constructed canvases and then painting them in a single sitting, until he realized he’s reached a dead end, working from ideas rather than feeling. He found a way out as he stood before a De Kooning, when one aspect of the painting opened up the approach his used from them on, which sounds akin to Agnes Martin’s methods in much of her work. He started to rely on an idiosyncratic grid as the seed for everything that followed–not as an aid for drawing a subject, but as a catalyst for feeling his way forward with the application of paint, creating a field of tensions and a sense of volume that guided how he applied his oil. The interview is fascinating.

JS: Yes. You made abstract paintings for many years before you started landscape-based paintings. The shift was received as very dramatic, but did it feel dramatic to you?

JB: Yes. It was huge. I was a cowboy-boot-wearing New York painter. I’m not a New York painter anymore. I am living in nature as the subject. The way I felt earlier could be summarized by de Kooning’s comment, “I wouldn’t paint a tree if you gave me a million dollars.” And for a year after I moved upstate, I was still doing the paintings I had been doing in New York: abstract paintings.

In my early days in Soho, a businessman who visited the studio remarked of a painting, “That looks like the most beautiful landscape on the worst possible day to see it.” I had titled the piece, Pennsylvania Road Trip. It was abstract, and I would have denied that it had anything to do with nature or the landscape. But it was inspired by this long bus trip I took to Pennsylvania. I was just blown away by nature as I looked out the bus window.

But living here (Catskills), I realize that I didn’t have a choice. I didn’t want to disguise nature. I realized that these spaces kept coming up in my work, and I had to go there. Young painters now know me as a representational painter. Many of my peers wonder what happened to the abstract painter. No matter what, I am still the same painter.

Even though my work now is landscape-based, it is more abstract than it was a few years ago. It is dealing with the space in the middle. At first I was painting the volume of the tree in space. Next, what I felt was that space itself has volume. And now, it is the light that has volume.

There is a phenomenological truth that exists in nature. Some days it is totally flat, other times and days, filled with endless voids and volume.

I never thought, because of my age, I would have enough time to shape, build and work with nature’s complexity. Now, I don’t want to depict nature; I want to paint nature’s phenomena. The painting is always the boss. I go where it says to go; it is endless. That’s the beauty of painting. That is its freedom. It all leads back to the horse.

If you want to understand the reference to the horse, read the interview, when he talks about his parents and the drawing of a horse his mother kept on the back of a picture of the Last Supper in their dining room. The relationship of form to void in that line drawing–his first exposure to art–prefigures the essence of what he was trying to do in his mature paintings.

Freedy Johnston and friends, in concert at The HiFi Bar, Sept. 8, 2016

Will Sheff: I was talking to Mike Stuto the owner of The HiFi Bar, and he was saying to me about that bar, “If I listen to somebody else about the bar, and I make changes to it, and it fails, I feel like a fool. But if I make my own decision and that fails, well I was wrong and I don’t feel ashamed about it.” I’ve come to believe that with success and failure, there’s a heavy degree of randomness, or maybe unknowableness and unpredictableness to it, but if you follow your heart or passion, then you kind of win.

Todd Barry: I guess we should both start singing “My Way” now.

–The Todd Barry Podcast #133

A few months ago, I discovered The HiFi Bar. Just writing that sentence reminds me of the Art Brut lyric: “I can’t believe I’ve only just discovered The Replacements.” (At least I’ve been a rabid fan of The Replacements for many years, but that doesn’t make up for having discovered The HiFi Bar this late.) It’s a unique refuge for music in a place smaller than almost anywhere I’ve heard music other than my own bedroom, a particular harbor of honesty and quality in a world devoted to everything but those two qualities. It’s aptly named because this is the sort of place I think John Cusack would have built when he decided to break out of retail LP sales and become a music producer at the end of High Fidelity. Walking in, before I understood where I was, I felt as if I’d found a home-away-from-home. Even without a performer on the tiny stage in back, it had the feel of a great, classic pub, like Pride of Spitalfields, near Brick Lane, where I once happened to be installed on a stool when a cohort of London policemen filed in for a retirement party. On that night, a few years ago, one of them seated himself at the upright piano to play a medley of Elton John and I asked him for some cuts off of Tumbleweed Connection, but he admitted he didn’t know the album. (How is this possible?) It was one of those warm and unguarded moments among strangers, full of heart, when you feel as if you’ve been adopted by the clan you’ve stumbled into, if only for an hour or two. My hours at HiFi last week were like that. I came away thinking, this is what practicing any art is about.

A week or two before I drove down to New York City, I bought tickets for Freedy Johnston’s performance there, and then read what little is out there about him. He’d been named Rolling Stone’s “Songwriter of the Year” in the mid-90s; he’d done recordings produced by T. Bone Burnett and Danny Kortchmar; he’d been celebrated by critics as a ‘songwriter’s songwriter.’ Yet, all of that, and this was the only concert I could find for him in all of last year in the usual listings. Why was he playing here? So I went back to the entrance, where the woman at the door was still awaiting newcomers, with her small list of those who had bought tickets to the show. My name was third down on the print-out of maybe twenty names, at most, and I could see she’d checked it off MORE

Pacifica, Kim Cogan, Maxwell Alexander Gallery, Sante Fe

My photograph, from the L.A. Art Show, doesn’t do it justice.

Persimmon and Stone, oil, Zhang Qing, China

Persimmon, oil on panel, Jeffrey Ripple, Arcadia Contemporary

There were both on view at the L.A. Art Show.

Water PPWG 16, detail, oil on canvas, Young-il Ahn, Korean

I spent Thursday afternoon at the L.A. Art Show, which concluded tonight. While much of it was of little or no interest, there were pockets of remarkable work, and I was gratified that my flight home got delayed by rain–denizens of Southern California apparently get premonitions of the world’s end when a steady rain begins to fall. Traffic slows dramatically. Jets get delayed. And all in reaction to a moderately steady rainfall. It’s pretty funny. (If you want a serious brush with death by weather, come to Rochester NY, and see what it takes to shut down the Thruway in January.) So I moved my flights a day forward, to Friday, giving me a leisurely visit to this big art fair which drew 70,000 people in 2016.

Toward the end of my meandering through the Convention Center, I came across a booth staffed by Baik Art, a gallery on La Cienega. Though the monochromatic surfaces looked at first like something I’d quickly forget, I turned a corner and saw a couple more of Young-il Ahn’s canvases and paused long enough to be drawn into them. I’d never heard of this painter before. The intelligent and perceptive young woman staffing the booth approached to tell me about him. He was born in Korea, moved to L.A. since the 60s, and now in his 70s, he’s been a painter for 50 years. He’s spent decades trying to capture the soul of the Pacific Ocean in these meditative images. I told her how much they impressed me.

“But don’t you wonder why?” I asked. “It’s a mystery, isn’t it, what makes such simple, repetitive images so good?”

She knew I wasn’t really asking. I would find it impossible to specify anything in the painter’s facture that struck me as exceptionally skillful, based on the standards I’d apply to most paintings. They were meticulously executed, which is obvious in the detail above, but trying to explain why the care he took with his mark-making has such a powerful impact on the viewer is like trying to pin down why the simplicities of Agnes Martin or Frederick Hammersley are so compelling and irresistible. You sense they adhere to some obsessive, personal imperative, so that every detail has been subjected to the most intense scrutiny and effort–and the energy of this kind of attention radiates from the surface. One feels the need to resort to come kind of corollary for Hindu distinctions between gross and subtle bodies–an invisible aura?–a whole metaphysics of painting that few people would find persuasive, including me. But my sense was that a quality, an X, akin to that kind of Vedantic distinction operates in all painting, so that something is conveyed through visual means by a painting as a whole, but is nowhere identifiable with any particular tangible qualities you can isolate and identify. You can easily spot the surface excellence in most paintings, but work like this conveys far more than pleasure and beauty and craftsmanship–and yet how to describe what that extra something is and how this transmission takes place? It’s nowhere and everywhere in the painting.

From the cover of the latest American Arts Quarterly, Richard Maury’s Vetrina, 2016, courtesy John Pence Gallery, San Francisco. His work reminds me of John Koch’s, but I love Maury’s work where I simply admire Koch’s. The light of a Koch interior is clearly the light of upper Manhattan, not the Mediterranean. It makes a huge difference to live and work in Florence, Italy. Nothing is lost in Maury’s shadows–everything in one of his paintings is lucid, glowing in a light that seems like the visual equivalent of happiness. That bright patch of yellow wall from the house across the way, glancing through the unseen window and bouncing off the glass of the framed drawing would have drawn as much praise from Proust as the little patch of yellow wall in the Vermeer he wrote about–but which has never been identified conclusively. Gazing at a Richard Maury painting is a fitting way to begin a new year: his work makes me think the future is bright for painting, where anything and everything is still possible.

From the cover of the latest American Arts Quarterly, Richard Maury’s Vetrina, 2016, courtesy John Pence Gallery, San Francisco. His work reminds me of John Koch’s, but I love Maury’s work where I simply admire Koch’s. The light of a Koch interior is clearly the light of upper Manhattan, not the Mediterranean. It makes a huge difference to live and work in Florence, Italy. Nothing is lost in Maury’s shadows–everything in one of his paintings is lucid, glowing in a light that seems like the visual equivalent of happiness. That bright patch of yellow wall from the house across the way, glancing through the unseen window and bouncing off the glass of the framed drawing would have drawn as much praise from Proust as the little patch of yellow wall in the Vermeer he wrote about–but which has never been identified conclusively. Gazing at a Richard Maury painting is a fitting way to begin a new year: his work makes me think the future is bright for painting, where anything and everything is still possible.

The Nativity, Piero della Francesca

‘A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

And the camels galled, sorefooted, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

and running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;

With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins.

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arriving at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you might say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

–T.S. Eliot

From Art Times:

In the summer, (Motherwell) lived and worked in a house on the harbor in Provincetown, Massachusetts. For most of the rest of the year he lived in a stone carriage house in Greenwich, Connecticut. In both places Motherwell created his abstract expressionist canvases and collages in houses that he redesigned to suit his own needs and those of his wife, photographer Renate Ponsold, and family. Both houses were spacious, casual, crammed with paintings and prints — his own and those of other major figures of his era . .

From a conversation taped in Provincetown in June 1986:

How important to you and your work is the place where you live?

RM: I was born in a seaport, and have always preferred to live in one. There is an old European saying that you dress for other people but eat for yourself. I feel the latter way about a home and couldn’t care less what anybody else thinks. What I like is informal, unpretentious – very much a studio feeling.

Have you always worked at home?

RM: From time to time I’ve been invited to work in California, Paris, wherever. I did it once and it was a disaster. I cannot work unless I’m surrounded by my own work and my own things. Most artists feel this way. You know the classic French artist’s studio was a wide room with beds and a kitchenette, slanting skylights and a little balcony. It’s not the bourgeois set-up with every room having an assigned function. The work going on in that open space is the essence of life. If you’re not home, near the studio, you can lose the best moments. There is something demonic about art that can’t be fitted into normal environments and sociability.

SPACE

Art About the Between

Clay is molded to make a vessel, but the utility of the vessel lies in the space where there is nothing. Thus, taking advantage of what is, we recognize the utility of what is not. – Laozi

This is not a call for works about outer space. Rather it is a call for works which explore the subtler concept of the distances or spaces between things, or spaces which things occupy. Examples include, but are by no means limited to NEGATIVE SPACE, EMPTY SPACE, DISTANCE, POSITIVE SPACE, DEPTH, PERSONAL SPACE, and so on.

People often take space for granted, neglecting to respect its importance in defining our world and understanding of reality. Our interest in how this theme is addressed by visual art is broad, and artists may interpret it widely when selecting works to submit. This call is an open question seeking an answer about how artists address space as a subject, or key aspect in the design and creation of their work.

This theme is very open to interpretation and to any and all visual arts media.

Submission deadline: January 4, 2017

http://www.manifestgallery.org/space

PLACE

Art About Location

Designed to complement its sister exhibition, SPACE, this exhibit seeks works MORE

Jim Mott at work

Some worthy notions from the mailbag, this time from Jim Mott, moderately incensed by a work of art he saw on a visit to the Memorial Art Gallery here in Rochester:

1

These thoughts were prompted by the MAG’s recent acquisition, a red sign that says “Knowledge is Power”. It has been mounted on the exterior of the museum, at the entrance. It is a jarring presence, an eyesore in what was one of the museum’s best parts. And the slogan itself is just very irritating in that context – a piece of empty visual noise, and the sad fulfillment of Tom Wolfe’s prediction for contemporary art in The Painted Word (1975): He noted that contemporary art had become so reliant on verbal theory that eventually words alone would be the visual art…

After a few days of extreme, maybe unreasonable, irritation, I did some research and found out the slogan was taken from a protest sign at Ferguson. <Jim went to Ferguson to paint for a bit on one of his itinerant tours. –dd> So it’s politically “relevant”…. But I think it’s idiotic for the acquisitions people not to see how the meaning has been lost – or worse – in the process of appropriation and decontextualization. It’s so opposite of what’s needed for art and for people viewing art. (I think I might not object much at all if the sign were inside, thoughtfully situated, with some contextualization. Maybe.)

2

Every artist – maybe every person – must feel, in childhood and youth, early stirrings of inspiration, intimations of power, glimpses of access to some great mystery that’s behind everything but usually hidden. The first question is, do you take it seriously, this elusive thing that no one else seems to notice or talk about? A sense of beauty and wonder and maybe later terror and uncertainty, all deep within, and deep without, maybe glimpsed in a dandelion, a speck of dust, a beam of light, frost crystals, the flight of a bird, the tone of someone’s voice… a significance barely there yet suddenly looming to a cosmic scale?

Do you serve the source or try to make it serve you? Is there a right answer? One, the other, neither, both?

I’m reminded of a conversation recounted by Dietrich Bonhoeffer in Letters and Papers From Prison. I read it in college. He said, when he was young, he had a friend in the church who wanted to become a saint. Bonhoeffer decided his ambition was to have faith. When I first read that I did not understand the significance of the choice. They were both abstractions and somehow did not feel relevant to me. So much was based on intuition back then; I did not have definitions for things.

Now I see how it might apply to anyone, of course, but particularly artists. It is about external status, worldly accomplishment versus relationship. Do you want to be a saint or have faith? Do you want to be famous, recognized, celebrated… or find ways to relate as transparently as you can to the source of your inspiration and to other people. Do you want your work to be bought by a museum or to move someone – not through sensation but through the realization of something deep or subtle shared.

The two are not of course mutually exclusive, even though I tend to think you must choose to give priority to one or the other. Sharing or relating – truly reaching people with your art can be enhanced by success, being collected, being deemed important. And in some cases art that effectively shares truth, beauty, inspiration, depth, wonder is taken seriously, does well in the marketplace. Sometimes there’s a hunger for it even there, if its packaged right. Although beware the hunger of the marketplace, that chews up and spits out and serves a power very different from the one that incites us to reverie and wonder.

Faith or honor, relationship or status. The people or the market. An artist should not have to dwell too much on such considerations, but a little bit, yes.

I think what bothered Jim most was the word “power” in the piece at MAG. My reaction would have been to be more skeptical about “knowledge.” The idea that visual art conveys “knowledge” puts it into a very Western, post-Enlightenment box, and constrains the way someone looks at the work, prompting them to ask of it certain things it may not have been meant to deliver–because it was busy conveying something more vital. Visual art is uniquely able to convey something far more encompassing than conscious knowledge strictly through perception, before thought can get to it.

Consider the lives of birds and fish. Fish never weary of the water; but you do not know the true mind of a fish, for you are not a fish. Birds never tire of the woods; but you do not know their real spirit, for you are not a bird. It is just the same with the religious, the poetical life: if you do not live it, you now nothing about it.

Consider the lives of birds and fish. Fish never weary of the water; but you do not know the true mind of a fish, for you are not a fish. Birds never tire of the woods; but you do not know their real spirit, for you are not a bird. It is just the same with the religious, the poetical life: if you do not live it, you now nothing about it.

–Kamo no Chomei, Hojoki (Ten Foot Square Hut)

The word painting could be substituted for “poetical” and Chomei’s thought would still apply.

Dana Gould

Dana Gould served as a guest host on Kevin Pollak’s podcast recently, and he had this exchange with his guest. I love the term “jam econo,” which isn’t just about money.

Jonah Ray: A lot of people want fame and money and if they have a knack for comedy they use that to get fame and money . . . lot of people go too big (in) how they go about things. Mike Watt, of the Minutemen, has this saying, “We jam econo.” Stay within your means. Do what you can within your own self. Don’t get further in your life or career on credit. Do it within your realm of possibilities.

Dana Gould: That was an understanding I came to about my stand-up career, and I think this applies to all people who consider themselves craftsmen or artists. It took me decades to come to this conclusion. So much of your career is, “if I get this, then I’ll get this.” Your career is now. You’re here. This is it. It’s great. If you are actively building your career, you’ve made it. If you are working at Barnes & Noble trying to gin up the balls to do an open mike, you haven’t made it. If you do an open mike, you’ve made it. The rest is just a level of degree.

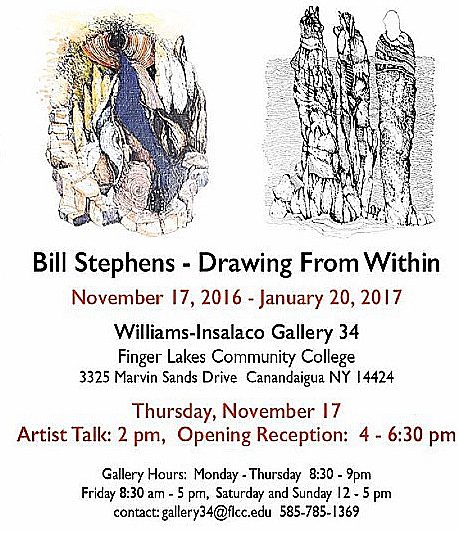

Drawing from Within, a solo show of drawings by Bill Stephens, is on view in the Wayne Williams and Tom Insalaco Gallery at Finger Lakes Community College. It isn’t a large space, but Bill’s drawings fit perfectly into it, and the show makes a striking impression when you walk in. Everything is framed and matted in such a way that his line drawings look, at a glance, as intricate as old engravings. He uses pens with an extremely fine point, creating form with cross-hatchings, Durer-like, never using solid blacks or grays. I’ve seen previews of this work at our get-togethers for coffee, and I’ve always been impressed, but the work makes a much deeper impression when you see it gathered together this way–the cumulative effect demonstrates how consistently his vision has emerged in this new direction for his work. His world holds together, stylistically, from each drawing to the next. They offer glimpses, from slightly different angles, into his unique and integrated inner world. Some of his images look almost like illustrations from Dante: clusters of souls migrating toward something beyond themselves.

What’s most interesting to me about Bill’s work is that the drawings are the outcome of a process rather than an attempt to render something already visible. His puts down lines and follows where they lead him, a journey to discover the forms that emerge as he improvises his way to an image that often fuses landscapes with botanical, animal, and human shapes. Everything seems an extension of everything else. The end result is surrealistic, and his process echoes surrealism’s “automatic writing,” letting the subconscious guide the hand. Yet as much as I was surprised to be reminded of Dali in many of these drawings, the feelings they evoke are far from the cool theatricality of Dali’s eerie, melting shapes. He’s enthralled by nature, and his enthusiasm infuses everything with a warm energy. He isn’t wedded to any particular sort of landscape–you can find echoes of his wooded Western New York backyard as well as the mesas of the Southwest. Mostly these are dreamscapes where vaguely recognizable forms emerge from the least expected sources–much of what he depicts seems to want to grow a pair of legs, even rock formations.

Bill’s talk about how and why he draws was completely extemporaneous and casual, yet it was often eloquent, and consistently illuminating. He says that each time he sits down in the morning in his studio, he brings a beginner’s mind to what he’s about to draw. For reference, he often refers to the notebooks he fills with quick, adept sketches when he travels, many times jotting quick, haiku-like impressions in the margins. He passed around these notebooks during his talk. The words hover around the edges, subordinate to the drawings. He and his wife, Jean, also an accomplished artist, are both enthralled by nature, and in their work they invest a spiritual depth into the simplest, most common and familiar aspects of the natural world, animal, plant and mineral.

In the days since Bill’s talk, having seen how intensely he’s venturing into this new series without knowing where it will lead, I’ve begun to realize that his process is, for me, a microcosm of how an artist’s career ought to evolve. The best work emerges from an effort to do something more and more consonant with the inarticulate feel of applying a medium in a certain way to a support–without knowing exactly where the effort will take you.The more you let other considerations come into play, the more they drain the life from the final image. Bill Santelli rode down to the show with me and on the way back we talked about how hard it is to stay focused on this factor of feeling one’s way forward in a particular painting, and, in a larger sense, in one’s career. The only reliable guide is to simply keep attempting to paint, or draw, what you most want to see. And you can work for years, or decades, without quite knowing what that is–or be constantly struggling to stay focused on it. Paint only what you want to look at: it sounds like the easiest thing in the world, but everything conspires to make you ignore that desire for any number of reasons: because what you might do won’t sell, or get shown, or be critically recognized, or because you want to belong to a particular “school” of work that has other requirements for admission. In these drawings, Stephens is answering only to what he wants to see emerge, line by line, and drawing by drawing, without any other consideration in play. And yet, groping forward in this way, sticking to process, he gets results that have an unexpected imaginative resonance.

In The Duino Elegies, Rilke spoke about how nature wants to “become invisible” through a certain kind of human reverence for it:

Earth, is it not this that you want: to rise

invisibly in us? – Is that not your dream,

to be invisible, one day? – Earth! Invisible!

What is your urgent command if not transformation?

I suspect in Rilke’s own life, this meant translating the tangible world into poetry. With Stephens, it’s just the reverse. His line, as he puts it down, creates its own necessity, so that while he draws he isn’t copying what he sees, but rather hopes his experience of nature will be translated, subconsciously, into tangible images that convey what might otherwise remain invisible, even to himself.

Candy Jar #9, oil on canvas, 52″ x 52″

Candy Jar #9 will be awarded Best in Show tonight at The Red Biennial, presented by The Cambridge Art Association, on view at the Kathryn Schultz Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The exhibition was jurored by Joseph D. Ketner II, the Henry and Lois Foster Chair in Contemporary Art Theory and Practice at Emerson College, Boston. He also holds the position of distinguished Curator-in-Residence. His professional expertise is as a curator and art historian specializing in European and American Modern and Contemporary Art, and nineteenth-century African-American art.

Agnes Martin, Cuba, New Mexico, 1970s

“You have to have a mind of winter to see nothing that is not there, and the nothing that is.” — Wallace Stevens

1

Agnes Martin painted like a thief. She seemed to be attempting to leave behind as little evidence of herself–or anything else–whenever she touched a canvas. It’s a self-effacing posture consistent with her immersion in Taoist spiritual traditions, and it’s part of what gives the rigorous austerity of her work its humble charm in the current Guggenheim retrospective. Yet as impersonal as the work appears, it’s often as beguiling as a simple, four- or five-note melody from nursery school. You climb the whorl of the Guggenheim’s spiral gallery, craving more than what’s there for much of the way. It makes you hungry for color, expecting to get it once you reach that museum’s higher elevations. Yet when it arrives, it leaves you wanting even more. Her tones are as faint and subtle as the pinks and blues in a Turner dawn. Meanwhile, there’s almost nothing to see in one pencilled spreadsheet grid after another, rows and columns of rectangles stacked on rectangles, each one as empty as the next. Then you’ll suddenly come upon a large, thin veil of paint that looks as soft and sensuous as felt or velour. The paint has a surface Thiebaud would have appreciated, though its almost the opposite of his impasto, more like a faint layer of powdered sugar on a cushion of icing, and, as if to heighten the effect through contrast, she scores that paint with a net of lines drawn into the still-soft medium. Again and again you feel a serene tension between the extreme simplicity of her means — the near-absence of all form — and the often sensuous, tactile surface, where the weave of the fabric, the absorbent gesso and finally the thin washes of paint all fuse to become a physical object that looks as if it were made to be stroked with your fingertips. (Which is an interesting urge considering the fact that she maintained she was trying to visualize an immaterial, spiritual state.) While the painting does seem to convey a state of mind, it also seduces you with its physicality. You note these polarities only if you stand and look with persistence, surrender to the static hum of her color or lack of it. Her art requires you to slow down and gives you almost nothing to think about. Judging from the evidence in this retrospective, it’s probably safe to assume she was constantly wondering how one might translate into paint the “no-mind” of Ch’an Buddhism’s Sixth Patriarch: awaken the mind without attaching it to anything.

2

I had never heard of Agnes Martin until four or five years ago, when for the first time I came upon one of her paintings, Untitled #6, at the MORE

I’ll be there for the talk, and for a tour of the show. I’ve been watching Bill work on this series for a while, and own one of the best ones he’s done. It’s fascinating work, and I have a sense that Bill is always balancing between conscious technique and subconscious impulse, tending the process without quite controlling where it leads or knowing where the drawing is going to end up. It unveils itself to him, as much as it does for the viewer. The one in my collection feels like an illustration for Dante’s Inferno, but a lot of the work seems biomorphic, the forms growing as naturally as seeds and branches.