Archive Page 28

January 18th, 2015 by dave dorsey

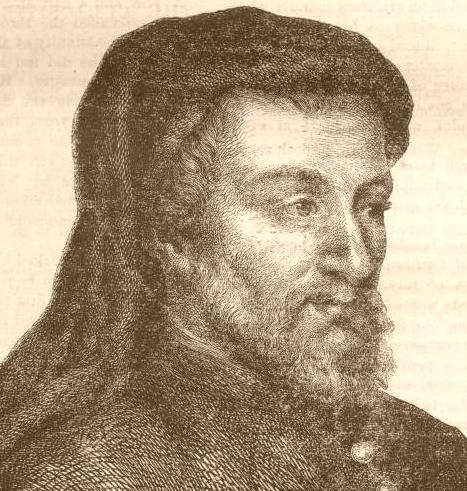

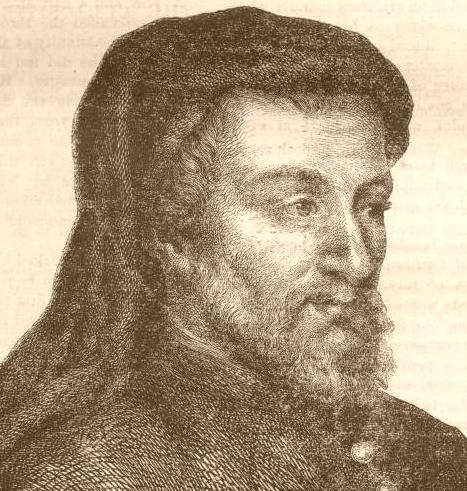

Chaucer, as new as he ever was

I was browsing through the squibs in the front of the most recent The New Yorker fresh from my mailbox, hoping to find something to see on a quick trip to Manhattan where Nancy and I, along with a couple friends, have tickets for the Matisse show at MoMA. I spotted three things that stood out, not for what they were critiquing, but for the thoughts expressed in these A.D.D.-friendly five-sentence reviews. Here they are:

1. Museum of Modern Art: “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in the Forever Now.”

“The ruling insight that the thoughtful curator Laura Hoptman proposes and the artists confirm is that anything attempted in painting now can’t help but be a do-over of something from the past, unless it’s so nugatory that nobody before thought to bother with it.”

(But my first response to this was: I will see your nugatory and raise you a negatory. Yes, history has run its course for visual art. The notion of progress is dead. But I have some humble qualifications that fly in the face of what I this show’s apparent tone and spirit. More below.)

I turned the page and found my counterpoint already put into words:

2. Marcus Roberts

While raising money on Kickstarter for his latest project–recording a suite of music that he wrote some twenty years ago, called “Romance, Swing, and the Blues”–the pianist and composer declared that “all great jazz is modern jazz–whatever the age of the piece, we make it ‘modern’ (relevant to our own time in history) when we play it.” This multi-stylistic dictum informs his work with his new twelve-member band, Modern Jazz Generation, which recently released a double album of the material.

(Obviously, right? The individual performer makes it new. Anyone who has heard a great cover knows this.)

3. “The Contract”

In the European Union, artists receive a royalty each time their works are resold. The U.S. has no such droit de suite, but in 1971 the curator-dealer Seith Siegelaub drafted a rarely used contract to guarantee artists fifteen percent of profits from future sales. The conceit of this show is that all the works in it . . . are subject to the agreement. Is this premise better suited to an article or a symposium than it is to an exhibition? Probably, but in this turbo-charged art market the show has the rare virtue of subordinating speculators’ profits to artists’ welfare. (The show, at Essex Street, was over on Jan. 11, even though this issue of The New Yorker is dated Jan. 12. Which is typical of these notices in The New Yorker: some seem to sit in the queue until after their use-by date.)

Last things first. I wish I’d seen this show just to have been in a place briefly MORE

January 16th, 2015 by dave dorsey

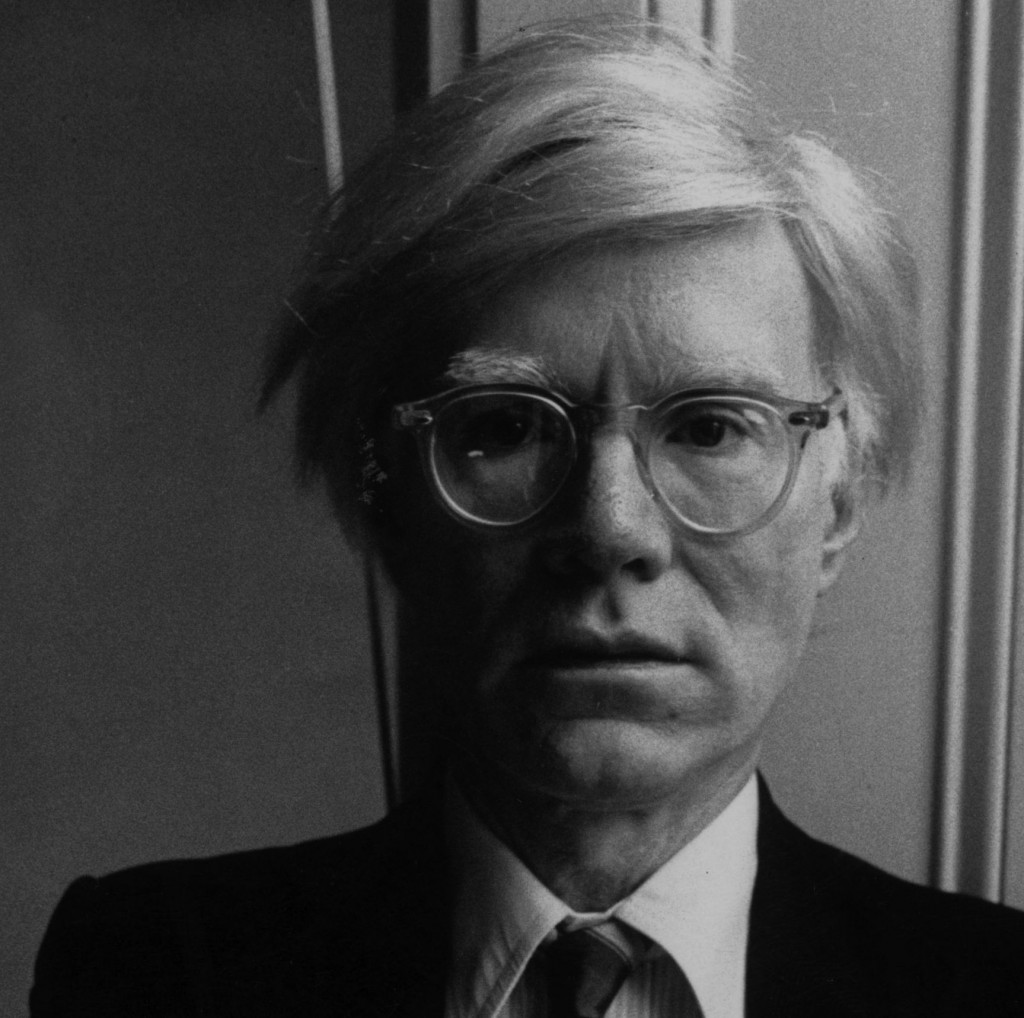

(Photo by John Minihan/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

From Kevin Pollack Show, #223:

Joel Murray: Back in the day, we were out one night, with Gilda Radner and my mother . . .

Kevin Pollak: We?

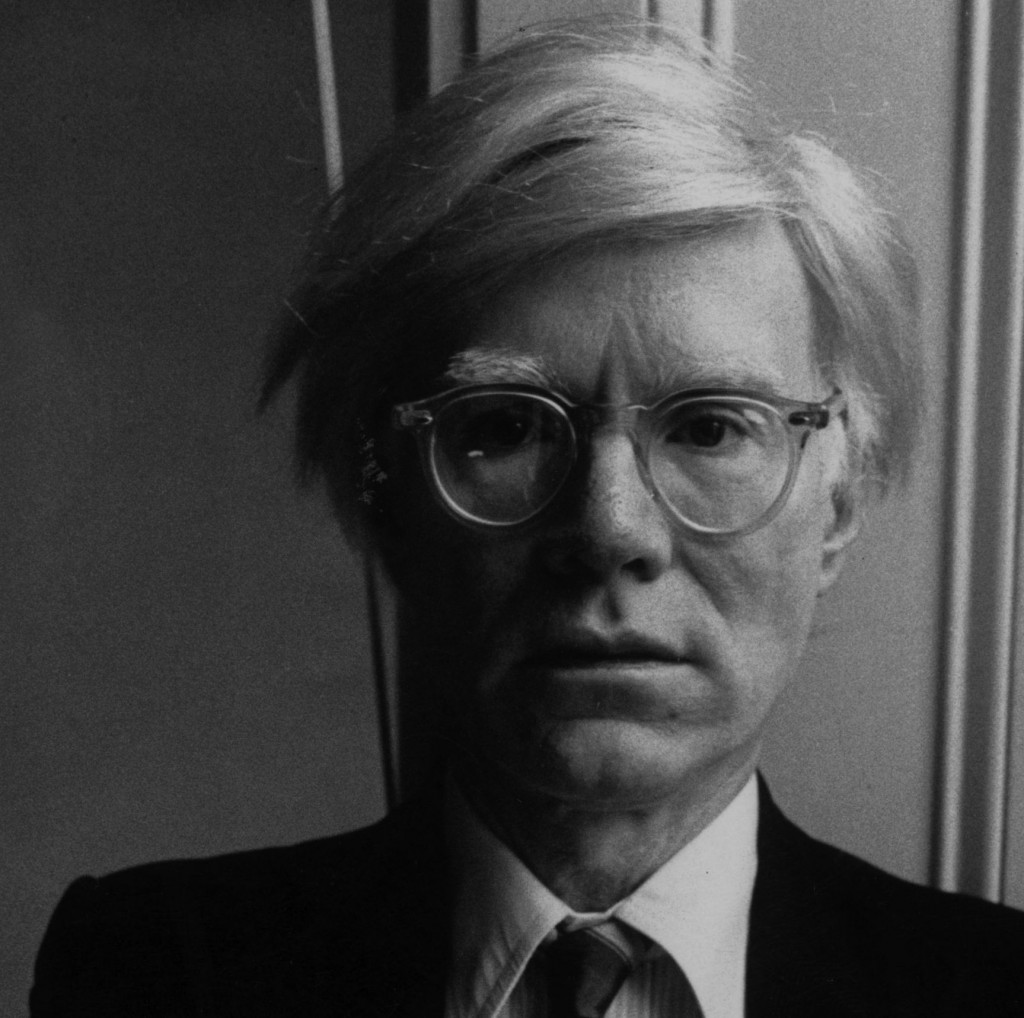

Joel Murray: My brother Brian and Bill. I wanna say this is the same night we saw Robin Williams at the Copacabana early in the evening with Lucy Arnez. Saw Robin do a show that blew us away. This is 1979, 1980. I laughed my ass off and I sat next to this strange guy who did not laugh once. White-haired fellow. I was like, who is the dead wood? Oh, that’s Andy Warhol. (Beat) Did not find the show funny.

Speaking of Warhol, even after he had become a major celebrity, I read this morning that Warhol more or less kept his day job, doing magazine illustration as late as 1986. That old Pittsburg work ethic dies hard. Plus, it was as much a work of art as anything else he did.

January 14th, 2015 by dave dorsey

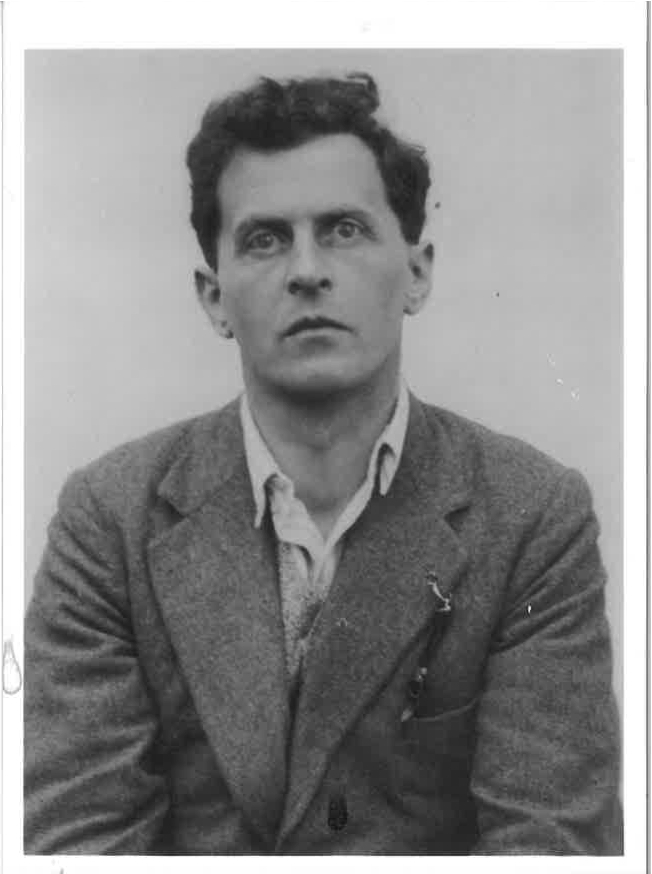

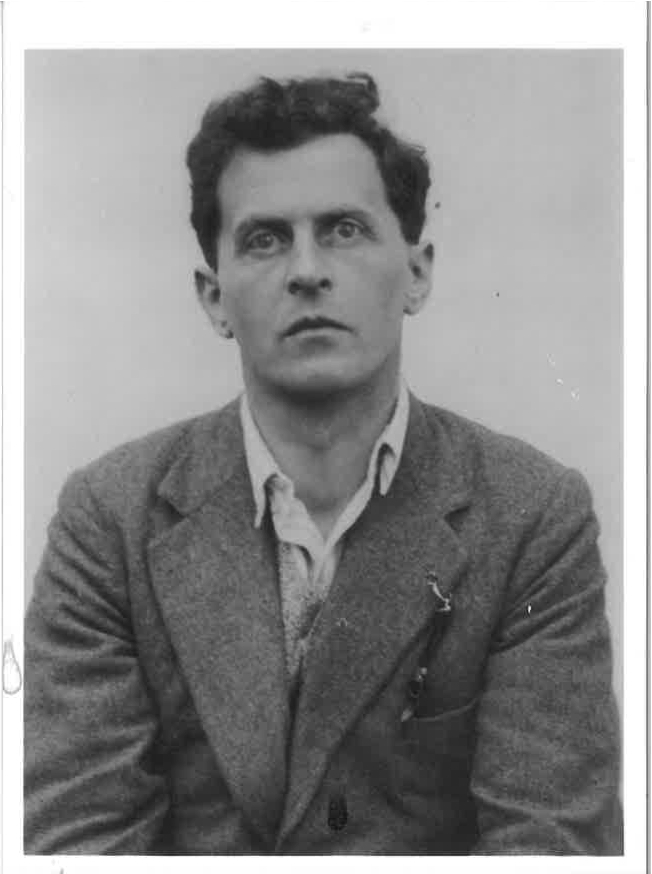

Ludwig Wittgenstein

A shot from a small piece where poets pick their favorite photographs in the Paris Review. (Speaking of which, I read a few days ago that George Plimpton was at Bobby Kennedy’s side when the candidate was shot. Did Plimpton ever do anything boring aside from brushing his teeth? I’m assuming he did it the way the rest of us do.) Ann Lauterbach, on this picture of Wittgeinstein:

The Wittgenstein photograph is unsettling; it’s as if he can barely see out from his mind’s fervent activity. There’s something eerie about looking back at him, into his uncomfortable, intelligent eyes, and thinking about the silence that every photograph compels us to acknowledge. I think about this silence often, and the indifference of images to it, and the ways in which captions try, but ultimately fail, to undermine it. Wittgenstein thought a lot about the relationship of silence to words . . .

As did Heidegger. Images as far more akin than writing (and thinking) to the silence Wittgenstein pondered. Poetry gets closer to it than any other form of writing. “Indifference” puzzles me: “The indifference of images to this silence.”

January 12th, 2015 by dave dorsey

It’s gonna need some windows.

Will Harlem become the new Bushwick? “We should be cultivating affordable housing in general.” http://bit.ly/1zZny6R

January 10th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Jim Mott’s oil of a dog walker he saw in Arizona

I could write a dozen posts based on my conversation this week with Jim Mott. Knowing me, I probably will eventually, one way or another, but one small point we talked about just surfaced while I was working on something entirely unrelated to painting. We both spoke about work habits and how difficult it can be to paint on a fixed schedule. He has intense resistance before sitting down to paint. He’s told me in the past that he approaches every new painting feeling as if he has to learn all over again how to make a picture, though he knows a wealth of things about how to paint. As painful as it is, he thrives on this sense of flailing at the start, struggling to simply get a grip on what he’s going to do, mark by mark–the instability of that moment seems necessary for getting a purchase on what has to be done each time he sits down to paint. My habits are much different. I have a set of methods that enable me to ignore those uncertainties, up to a point, and they make the earlier stages of building a painting almost routine–with the exception of the first stage, seeing the image I want to paint. That’s when I feel exactly as Jim does. Discovering that image is really the first moment of anxiety and struggle for me. Since I work with photographs I’ve taken, I can spend half a day or most of a day, just trying to compose and capture a picture that will end up as the source for a painting. Jim faces the same uncertainty when he wanders through a landscape looking for what he’s going to paint–and he had a funny story about how, on one of his peregrinations, he used a GPS coordinate generator to find utterly random scenes, and how he forced himself to paint even the most unappetizing views of the region, based on the locations his software calculated. He forced himself to stick with the locations without, as it were, rolling the dice again.

Normally, for me, finding a picture just means working within the slightest variations of light and setting around my own home, involving a few objects I’ve painted before. It’s amazing how difficult this can be, because I need to have some kind of emotional response to what I’m seeing; there has to be something enticing about recreating it in paint, and that’s not easy to inspire, even if I’m simply setting up a still life in an artificial way. It’s never a sure thing. I can even come up with a shot that I believe is exactly what I need but when I begin to paint it, I realize it won’t come together properly, and I abandon the painting. Also, I can lose what felt like a compelling image in the middle of painting it, which is when the struggle returns. There’s a point in almost every painting where I start doing things I don’t know how to do–problems I haven’t had to solve before. I discard far more paintings than I would like, but that moment of deciding that a painting doesn’t work–and it can be even after the painting is finished–is close to the mysterious crux at the heart of what painting is. A painting has to live, which is different from saying a representational image needs to resemble life itself. A painting can be an exact replica of what’s in front of the lens, either an eye’s or a camera’s, but that doesn’t mean it will come alive for a viewer. It needs to do more than simply look real; it needs to feel alive, both as a scene, and as a physical object on a wall. That comes, in my view, from the difficult delight of laboring, with an appetite for the work, hours and days and weeks or months, making a thousand marks, and another thousand, with a sense of wanting the paint itself to convey its own vitality, in addition to the way it persuades the eye that it isn’t simply looking at paint. To be that invested in something as fundamental and physical and mostly subservient as the act of painting is what’s required for the final work to strike others as vital and arresting. But what that life is, the quality of both presence and absence a good painting has, as people themselves do, the way it discloses and offers so much while also giving the sense of withholding just as much, and leaving so much out, unarticulated–there doesn’t seem to be any way of objectifying how this happens, or even describing it. The routines only take me so far, and then I’m as adrift as Jim before he starts working, from start to finish. The best indication that it’s coming together though, is nothing more authoritative than a feeling (which sounds nebulous but isn’t), a sense of anticipation and a willingness to keep working on a particularly tough section until it’s right, a surrender to the terms of what’s beginning to appear as you realize the unique challenge the work represents. Keeping that hunger alive, the appetite to keep applying paint, even when something resists everything you already know how to do, is what eventually makes the painting work. It’s something an individual achieves alone, and can’t be taught, though it’s easy to see its results in all the great paintings of the past. Seeing it in previous paintings is how I realized I wanted to paint in my teens.

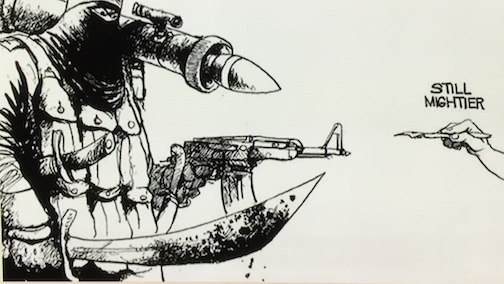

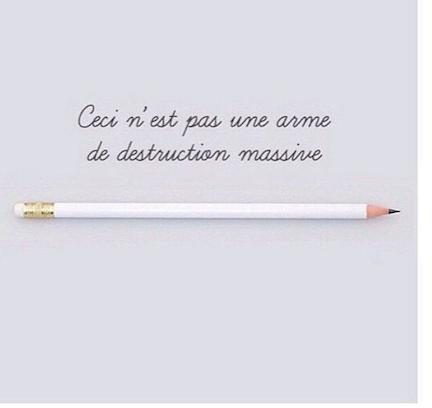

January 8th, 2015 by dave dorsey

January 6th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I spent a couple hours talking with Jim Mott yesterday, which I’ll write about shortly, but I wanted to pass along this nice opening paragraph from the September New York Review of Books he gave me:

“Imagine the Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art as the perfect storm. And at the center of the perfect storm there is a perfect vacuum. The storm is everything going on around Jeff Koons: the multimillion-dollar auction prices, the blue chip dealers, the hyperbolic claims of the critics, the adulation and the controversy and the public that quite naturally wants to know what all the fuss is about. The vacuum is the work itself, displayed on five of the six floors of the Whitney, a succession of pop culture trophies so emotionally dead that museumgoers appear a little dazed as they dutifully take out their iPhones and produce their selfies.

Of course even those who take a serious interest in Koons know that he’s also full of baloney. Roberta Smith, reviewing the Whitney retrospective in the Times, comments on his “slightly nonsensical Koonspeak that casts him as the truest believer in a cult of his own invention.” That is well put. The essential fact about the Koons cult, however, is not that Koons invented it, but that it has gained such extraordinary traction, in the art world and well beyond. Day after day, the crowds are lining up outside the Whitney, waiting to get in to see the Jeff Koons show. What are they to make of the tens of millions of dollars that have been squandered on this work? What are they to make of the critics and historians who are defending Koons with a belligerence that allows for no debate? And what are they to make of the Whitney Museum of American Art?

That Koons will be Koons is his own business. That he has had his way with the art world is everybody’s business. No wonder the people in the galleries at the Whitney look a little dazed. The Koons cult has triumphed. For his next project Koons should consider manufacturing a ten-foot-high polychromed aluminum Kool-Aid container.

Jed Perl, New York Review of Books

December 29th, 2014 by dave dorsey

“Chief among the virtues is gratitude. Friendship would be a close second.”

–Robert Harrison, Entitled Opinions, 2006

December 27th, 2014 by dave dorsey

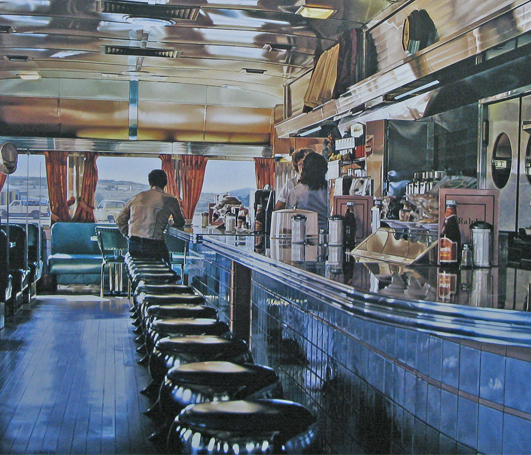

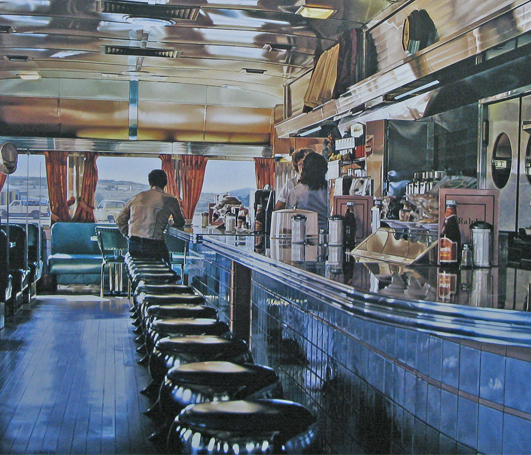

Ralph Goings, Ralph’s Diner (1981-1982), Oil on canvas.

Not surprisingly, the deadline for being an originator of photo-realism has long since passed, but photo-realism itself is still alive and well, though it doesn’t attract much critical attention. It was interesting and a little amusing to run across (in Wikipedia) these “rules” for determining whether an artist was an originator of photo-realism, or just a late-coming follower of the school. My response to Rule Number Three . . . well, yeah.

The word Photorealism was coined by Louis K. Meisel in 1969 and appeared in print for the first time in 1970 in a Whitney Museum catalogue for the show “Twenty-two Realists.” It is also sometimes labeled as Super-Realism, New Realism, Sharp Focus Realism, or Hyper-Realism.

Louis K. Meisel, two years later, developed a five-point definition at the request of Stuart M. Speiser, who had commissioned a large collection of works by the Photorealists, which later developed into a traveling show known as ‘Photo-Realism 1973: The Stuart M. Speiser Collection’, which was donated to the Smithsonian in 1978 and is shown in several of its museums as well as traveling under the auspices of SITE. The definition for the ORIGINATORS was as follows:

1. The Photo-Realist uses the camera and photograph to gather information.

2. The Photo-Realist uses a mechanical or semimechanical means to transfer the information to the canvas.

3. The Photo-Realist must have the technical ability to make the finished work appear photographic.

4. The artist must have exhibited work as a Photo-Realist by 1972 to be considered one of the central Photo-Realists.

5. The artist must have devoted at least five years to the development and exhibition of Photo-Realist work.

What’s missing in the way most people talk about photo-realism is the power it derives from its having been built slowly, with physical objects and substances, not simply because it’s an amazingly skillful duplication of a photographic image. Something essential goes into the painting, which wasn’t present in the photograph, even when the finished work looks like an exact replica of the photo. (Though even the best photo-realist work rarely looks exactly like a photograph.) I think what distinguishes the painting of an image captured with a camera (and this is obviously part of what makes Vermeer, the original photo-realist, great) has to do with the “aura” of an original work of art, which Walter Benjamin dismissed as something mass media had exterminated. Not so fast. The physical act of making a painting, one brushstroke at a time–whether it’s abstract expressionism or photo-realism or anything in between–conveys something tangible but difficult to name. It also alters the photographic image incrementally in a hundred small ways that have to do with an artist’s unique preferences and taste. If you gave the same photograph to two different photo-realists, you would be able to distinguish one painting from the other, no matter how similar they were, and those differences embody the unique ways an artist gets his materials to obey him, or doesn’t–and then learns to adapt to what he can and can’t do with paint. All of this gives a painting its personality, presence, and the sense that it’s somehow alive. The essence of a photograph, its vitality and power, isn’t tied to a specific physical object, in a particular place–I think it’s far more infinitely reproducible. A photo-realist painting brings the image back into the physical world. It’s as much an object on the earth as the person who made it, and the essence of a painting is connected to the limitation of its physical nature, which is also its unique advantage, and part of what essentially makes the great paintings so expensive. In their own way, they’re one of a kind, even if they look exactly like something that could have been reproduced a million times.

December 25th, 2014 by dave dorsey

![Mosaic icon of the Virgin Episkepsis, late 13th century [Credit: Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens]](https://thedorseypost.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/madonna-and-Child-892x1024.jpg)

Mosaic icon of the Virgin Episkepsis, late 13th century [Credit: Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens]

December 21st, 2014 by dave dorsey

“The sun that reigned over my childhood freed me from all resentment.”

–Albert Camus

Camus was born in Algeria, Nov. 7, 1913.

His father was a poor agricultural worker. His mother was illiterate and nearly deaf and worked as a “domestic.” A cleaning lady.

When Camus was less than a year old, his father died as a result of his wounds in World War I.

His mother moved her family into his grandmother’s three-bedroom apartment in the Arab Quarter of Algiers. They lived there with his mother’s two brothers, six family members in all. The grandmother was domineering, cruel, and ostensibly carried a whip made from the neck ligament of a bull. Apparently, she was all Albert had, until he found some books. The apartment had no electricity or running water; the toilets were on the landing and shared with the two other apartments in the block.

In his acceptance for the Nobel Prize, he said, about the current terrorism in Algeria, as it struggled to free itself from France, “‘People are now planting bombs on the tramway of Algiers. My mother might be on one of those tramways. If that is justice, then I prefer my mother.”

His remark caused a stir in Paris. Sartre, the Marxist, accused him of having the “morality of a Boy Scout.” Yet it was a philosophical stance, not a sentimental one, placing a value on individual human life above all ideology or political agendas. It was really an extension of things he’d written in The Rebel. He was one of the writers who got me through college, thanks to an extracurricular reading list I assembled myself. Life happens, one human relationship at a time, and Camus pointed out that ideas and ideology and theories and “isms” blind everyone to the humble fact that one human encounter at a time is all we have. The rest is automatic pilot. I think of it as humble friendship. Theories kill or cost way more than they’re worth. Meaning follows perception and action; things and people matter more than any meaning you can attach to them consciously, or creatively–and on their own have a complex human significance you can’t package as a metaphor or turn into a message. If that finds its way subliminally from the work to the viewer, it’s because the artist gets out of the way and lets it happen, one friend to another.

December 19th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Christie’s priced this Baselitz at around $600,000. How does he make ends meet?

An article on Georg Baselitz in The Independent seems designed to make your jaw drop. Aside from the comments about female artists, there is an equally funny remark from someone pushing back against Baselitz by dissing him, on the grounds that his work doesn’t pass the sales test he sets up in his remarks. The point is that the highest price his work has fetched is “only” $4.5 million. That says more about the haywire perspective here than anything else. My riposte to Baselitz would be nothing but a list of female painters whose work I love, or at least like quite a bit: Martin, Frankenthaler, Riley, Saville, O’Keefe, Matthiasdottir, Fish, Freilicher, Krasner, Cassatt. . . and quite a few lesser-known women I’ve written about here. I’m surprised he didn’t fault women for failing to turn their images upside down. From The Independent:

Women cannot paint well, despite making up the majority of art students, according to one of Europe’s pre-eminent post-war artists. Georg Baselitz, who was lauded by the Royal Academy five years ago as one of the greatest living artists, dismissed women painters, saying that they “simply don’t pass the market test, the value test”, adding: “As always, the market is right.”

“Women don’t paint very well. It’s a fact,” the 75-year-old German artist told the German newspaper Der Spiegel. “And that despite the fact that they still constitute the majority of students in the art academies.”

Baselitz conceded there were exceptions, pointing to Agnes Martin, Cecily Brown and Rosemarie Trockel. After praising Paula Modersohn-Becker, however, he added that “she is no Picasso, no Modigliani and no Gauguin”.

Griselda Pollock . . . co-author of Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, said: “Only few men paint brilliantly and it’s not their masculinity that makes them brilliant. It’s their individuality. Baselitz says women don’t paint very well, with a few exceptions. Men don’t paint very well either, with a few exceptions.”

Sarah Thornton, who wrote Seven Days in the Art World, said: “I disagree with him; the market gets it wrong all the time. To see the market as a mark of quality is going down a delusional path. I’m shocked Baselitz does. His work doesn’t go for so much.”

The record for a work by Baselitz was £3.2m in 2011 for his work Spekulatius.

“Men don’t paint very well either.” Just that and nothing more would have been the perfect response.

December 17th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Almost done. Only the onion to go, plus a little smoothing on the blue walls of the dining room behind the still life. I’ve been thinking of a show built around “interior still lifes” where the surrounding room is as significant as the everyday objects in the forefront. I’m doing this one mostly a familiar and reliable way, one section at a time, working each small area to completion and then moving on, though in places I’m doing lobes of flat color to establish comparative values and then I drop in, by air, and start wandering around in there, raising up actual terrain, wet-on-wet, within those flat mapped out areas of color. I’m going to finish the onion gradually, one centimeter at a time. That’s a carved wooden table my parents gave us, with a couple leafs to allow all of to get around it. Around the table will be our daughter and son-in-law, their new baby, Poppy, along with our son-in-law’s parents, and my parents and my brother. At the center of it all, emotionally, will be the new baby, and then the rest of us who are just hanging around hoping for good things from these younger people. The blue walls and white chair rail in the room were Nancy’s choice, so it’s a kind of earth-and-sky thing in the painting, with the blue napkin under the candy dish. (An onion is like candy to a real cook, isn’t it?) I lied about that wall color when I changed it to a dull orange in a quick still life of a cream pitcher on that same table, which I sold in my last show at Oxford Gallery two years ago. I miss that painting. This is a completely different piece of work. There’s more Velazquez than Manet in this one, though that was something I realized only as it was happening. (Manet worked under that Spanish influence and broke free of it without losing everything it taught him, but I’m splitting the difference here a bit.) The onion is going to be a challenge, with the satiny color of that translucent and bronze skin, but that’s making me eager to get to the easel as early in the morning as I can. This painting has been a turning point for me in my work for the two-artist show at Oxford Gallery in March, because from the very start I couldn’t wait to get back to it, just wanting to dig with paint into the carved shapes of that wooden table. (I was even thinking about this painting while I sat at the bar at Parnell’s on First Avenue last weekend, three hundred miles away from it.) It felt like reshaping that table with my brush as I made those relief carvings appear on linen. It grew out of a photograph and I didn’t settle on the image until, eventually, I aimed the camera downward to do justice to that table and the way the light played on it. Maybe I’ve made that onion harder to reach than ever, having jinxed the process by talking about it. We’ll see.

December 15th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Being a midwife rather than a dictator suggests to me the difference between Braque and Picasso. Einstein puts the hair into perspective too.

Being a midwife rather than a dictator suggests to me the difference between Braque and Picasso. Einstein puts the hair into perspective too.

From The Guardian:

So, anyway, album of the year! Hooray! Did you feel that St Vincent would be so critically acclaimed as you were making it?

[Laughs.] I mean, no! It’s not that it felt bad, more that I don’t write from the point of getting critical success. That feels like a quick way to artistic death labyrinth. You have to approach the creative process with reverence and respect, but you also have to give yourself over to it and say: “The music will tell you what it wants to be, so try and get out of the way, try and be a midwife instead of a dictator.” . . . It was kind of like … I don’t have children, but this is what I imagine having children would be like. I’m from a family with a lot of kids, and I was later down the line … by the third kid, or the seventh kid, you’re just like: “Yeah, stay out as late as you want! Do whatever!” You learn to just let them be what they want to be.

The Guardian review of St Vincent claimed that your style icon is Einstein …

Yeah, I’m quite an Einstein fan. I love that he only had one outfit because he needed to conserve brain space. He essentially had a uniform so that he didn’t have to think. When you can make those macro decisions automatically, you free up a lot of time for more important things.

Have you taken this on in your own life?

Yeah … I mean, I’m organised. I’m obsessed with the idea of building systems and how systems work. So I’m definitely the person who spends their time creating the system and then implements the system. That way, you’re not reinventing the wheel every single day.

December 13th, 2014 by dave dorsey

At Quartz, someone actually wrote this:

At Quartz, someone actually wrote this:

“Anyone who is a serious member of the creative class,” Art Basel director Marc Spiegler told Reuters last week, “is going to come into our fair. We’re getting a lot of requests from CEOs and CMOs who’ve never come to the fair.” In other words, there is a legitimate turn taking place as the idea of an immensely lucrative contemporary art market ceases to seem like a sign some market bubble is about to pop. With each passing year, contemporary art becomes a more plausible tent-pole for the global creative economy.

I love how two sentences can herd the creative class into very close quarters with CEOs. The opportunity and income gap is nowhere more extreme than in art. As soon as someone says a hyper-inflated market for things of extremely flexible value isn’t a bubble, you know it’s a bubble. A long-lasting one, maybe, but nevertheless. The point of the article is that art may be going the way of high-end cuisine, becoming accessible to a far larger market, though it seems it might be compared more accurately to tulip bulbs than to the latest iteration of risotto with chile oil.

“Anyone who is a serious member of the creative class is going to come to our fair.” I could make a long list of names of hugely talented members of the creative class who don’t have the time for it because they are too busy being creative.

The Economist explains that the big fair has spawned a lot of satellite events and galleries, as well as parties, and whatever money settles into that river delta of spending will go to emerging artists. Fair enough, no pun intended. But mostly its a carnival of conspicuous consumption, isn’t it?

Throughout all this, Miamians put up with the influx of cognoscenti and socialites with good humour. It does not matter that the traffic is snarled up and pretentious outsiders are flaunting their bulging bank accounts; this is a colourful pageant that not only bolsters the local economy but showcases genuine, creative talent. And with winter setting in elsewhere, the warm sunshine is fantastic. The city has come a long way from being the place where, as Lenny Bruce put it in the 1970s, ”neon goes to die”.

For a week or two, then, the exceptional artist who has merely average income might have a chance to happen upon people who love his or her work enough to pay for it. But it’s hard to see how this helps most galleries in New York City or in smaller cities around the country actually stay in the black from month to month. And it’s hard to imagine decent little galleries in mid-sized cities being able to afford a presence at Art Basel.

The Quartz article suggests to me that primarily Art Basel still offers the super-rich an opportunity to sell to the super-rich with a growing attendance from actually creative people who show up out of voyeuristic curiosity. The premise is that the world is becoming more and more visually sophisticated, thanks to Instagram, Facebook, and a life increasingly devoted to looking at electronic screens for communication, information and entertainment. What the article doesn’t explore is how the economics of all this would actually change in favor of the middle class: how the affordable mid-value work, what used to be the emerging effort that had the most potential to go up in value, if a beginning collector placed his or her bets properly, now gets overlooked in favor of the obscenely priced work which appears to be guaranteed to increase in value. The illusion of this insulated jet-set economy is that the creative risk of the buyer has been removed: it’s an investment with a lock on profit. That does impose on visual art a tent-pole mentality from the movie industry, though it’s hard to see how sales at Art Basel will help fund the work of artists who make little for their efforts, the way a major movie could give a studio enough profit to make lesser, award-worthy fare. I guess the answer would be: come to Miami and put up your little booth and try to tell your work once a year to the buyers who can’t afford Koons. The tent-pole model has already been adopted by the book business, with its focus on blockbuster tomes at the expense of the mid-list. I’m not sure how the entire “creative class” will benefit from the fact that unimaginable sums of money move from one enormous bank account to another as a result of a big art fair. Good movies can still make money. Good books too. Good paintings as well. There is some fine work at Art Basel. But as always, art fair or no art fair, it’s a tiny percentile of the creative class who can actually do it for a living, and to have to start modeling one’s idea of how to reach people with a painting on what happens at Art Basel is a very depressing prospect.

December 9th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Marching NYC, 1943, Arthur Leipzig, Harold Greenburg Gallery

From New York Times, Dec. 5, via Walt Thomas:

To look at these pictures today is to catch intimations of the evanescence of both youth and a city. In his 1995 book, “Growing Up in New York,” Mr. Leipzig called himself “witness to a time that no longer exists, a more innocent time.”

“We believed in hope,” he wrote.

He began photographing New York children in the early 1940s and continued, off and on, into the mid-1960s. He said his inspiration was “Children’s Games,” a 1560 painting by the Flemish master Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Mr. Leipzig was intrigued, he said, that the games played in Renaissance-era Flanders were similar to the ones he observed outside his window…

…At the Photo League, Mr. Leipzig studied under Sid Grossman, who urged him to apply intuition to his growing knowledge of composition and technique. At the beginning of the course, Mr. Grossman sent him to MoMA three times until he finally reported being moved by a painting, a Picasso.

“Now we can begin to work,” Mr. Grossman said, according to Mr. Leipzig in his 2005 book, “On Assignment.”

December 8th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Self-Portrait c.1799 by Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775-1851

From a friend who listens to Mark Kermode’s podcast, which I do as well, but haven’t had time for it in a while: “Kermode said regarding Mr. Turner that he has never done such a positive review of a movie and yet had so many negative responses to the movie and his review.” Below is a passage from his review in The Guardian which ended with this line, ” . . . this (is an) awards-worthy portrait of a man wrestling light with his hands as if it were a physical element: tangible, malleable, corporeal.”

While his art engages, Turner’s personal life is depicted as increasingly insular and alienated, particularly in relation to the women who fall into his selfish circle. An early abrasive encounter with Mrs Danby (Ruth Sheen), by whom he has fathered two neglected daughters, establishes the artist as cruelly unwilling to acknowledge his adult responsibilities, preferring to be pampered by his own father rather than shoulder the burdens (and bereavements) of paternity. Meanwhile, housekeeper Hannah (Dorothy Atkinson, strong yet pitch-perfectly pitiable) dutifully accommodates Turner’s random needs for sexual relief, her own unspoken affections unmatched by his physical advances, which have the character of an assault. Brothels are visited for inspiration; the corpse of a drowned woman fires a feverish creative urge. Only in his relationship with Margate widow Mrs Booth (Marion Bailey) does Turner seem able to make an intimate personal connection.

For all its evident admiration of his work and legacy (Turner refuses to sell his paintings for a handsome £100,000, insisting that they will be left to the nation), this is also an honestly unsympathetic portrait of the artist as an aging man. On the canvas there is great beauty, while in his life there is ugliness aplenty.

Can’t wait to see it, the beauty and the ugliness both. The friend who called my attention to this also questioned my notion that loving a particular artist’s work is a kind of friendship with that artist–that the work conveys to you the man or woman who made it. There’s a crackpot theory that Walter Sickert was actually Jack the Ripper, and I agree that you can’t get to know Sickert quite well enough through his work to intuit that he liked to kill his models. What you do get to know, in a global way, through an artist’s work is the nature of that person as an artist: which involves a whole range of intuitions beyond what an artist thinks he or she is doing while creating a work of art. My love of Louisa Mattiasdottir’s work doesn’t tell me anything about how she behaved when she wasn’t painting, but all of the aesthetic choices she made in each painting, intentionally or not, consistently show me a complex set of perceptions that hang together in a way that adds up to her vision of the world. It adds up to who she is, as a painter. I don’t need to enumerate all the qualities her choices embody: intense and sustained emotion in an austere landscape, the ability to see the beauty of a particular sweater or a cluster of sheep (if that horizontally striped sweater was wool, who knows, there’s even more going on there maybe . . . ). In admiring her work, I have the equivalent of a friendship with someone who was able to see the beauty of simplicity and constraint, both in the Icelandic climate she apparently loved and in the way she painted. When I look, say, at Basquiat’s work, I see something almost entirely the opposite, and I find it unfriendly, even though many others see childlike exuberance in what he did. That doesn’t mean I think the work is bad. I just don’t have much affinity for it, and since I’m not a professional critic, I don’t need to know more than that.

Turner’s an interesting test of this friendship theory. I’m good friends with him, in his identity as a painter, but maybe I wouldn’t want to spent much time with him over a pint. Though I’m not sure I’d rule that out. I think artists are their best selves while painting, or at least their most effective selves, and that’s the person I want to spend time with and get to know–through the painting, not through the biopic. And what I get from a painting or a body of work is as complex and subtle and partly subconscious as what I gain through actual friendship with the people around me in my non-painting life. It’s holistic, not conceptual.

December 6th, 2014 by dave dorsey

I don’t think Artsy wants to eliminate this.

Following up on my last post, about Artsy, at ArtSlant there’s an interesting rumination on whether online exhibitions of art can ever replace the experience of seeing work in a physical space. I think it’s a misunderstanding of what Artsy is attempting to do. It might occasionally enable people to give up brick-and-mortar exhibitions, but that isn’t the point. It’s more of an attempt to enable people to find exactly what they want in art and then track it down in the physical world, if they like. It doesn’t appear to me that Artsy is trying to replace galleries and museums, but rather give people a way to connect more effectively with them. You can read “Do We Need Galleries Anymore” here at ArtSlant. The writer also mentions Walter Benjamin’s views on the “aura” of a work of art, which can be encountered only by being in the presence of the work itself, but in my reading of Benjamin, it seemed that he was quite happy to see the artwork’s spurious (in his view) “aura” disappear in favor of mass access to art, through mechanical reproduction. So he would support online exhibitions and access, and be pleased to see galleries disappear. He was basically a Marxist who recognized that the art business was a mainstay of capitalism: reproduction of works would make them accessible to anyone, regardless of income. I like the notion of making art accessible to anyone, but that doesn’t mean that the original would lose its value, neither in its “aura” nor in its economic value. John Berger was dreaming when he took Benjamin’s view and went on to say that “the modern means of production have destroyed the authority of art. For the first time ever, images of art have become ephemeral, ubiquitous, insubstantial, available, valueless, free.” Digital images of them have achieved that status, but not the work itself. In other words, everybody wins: those who want to see the work but can’t afford to do that in person, or own it, and those few who can own the original as well.

December 4th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Jon Pestoni, Windshield, 2014, from the Artsy overview of Art Basel

I’m finally recovering enough time and attention to sit up and look around after one of those months of needing to neglect everything I thought I needed to do–but which I guess I didn’t need to do, since it didn’t get done. Such as writing this blog. Still, it felt as if I were goofing off, when I was actually busy getting through November. I hate that: busy but feeling like a slacker. But December is here and I can see a bit beyond my To Do list. One of the first things I saw this morning was Artsy, a new website and organization that looks poised to do something extremely useful (probably, it’s already doing it, and I’m way behind the curve, but they are hiring a lot of people, so that seems at least semi-poised . . .) It appears to be devoted to giving people a central place for following what’s happening in art and maybe finding ways to buy some of it or simply learn more about it. The website design is beautiful, simple, sophisticated, and friendly, If I’m understanding it properly, among other things, Artsy wants to use algorithms to make it easier to identify art that might be of interest to you and see connections with other art that might not have been obvious before. And follow nearly anything or anyone connected to the making or exhibiting or sale of art. That’s the key: a combination of the best elements of Pandora and Twitter and Spotify and Instagram. It can help you stay on top of what’s happening at exhibitions and art fairs, be a sort of concierge for collectors, and it offers an iPhone app that even allows you to organize art on your phone and serves as a guide for any art fair Artsy hosts.

One thing that comes through, this isn’t your typical little start-up. I don’t MORE

December 1st, 2014 by dave dorsey

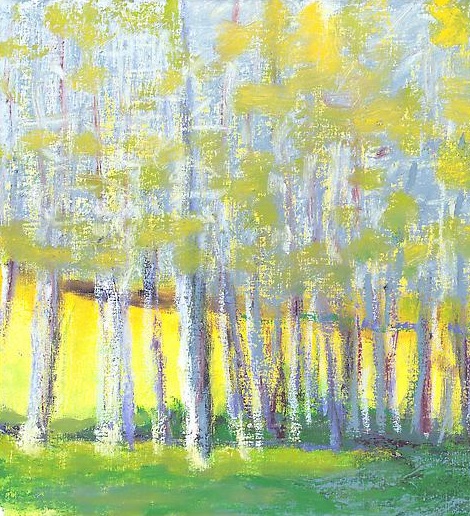

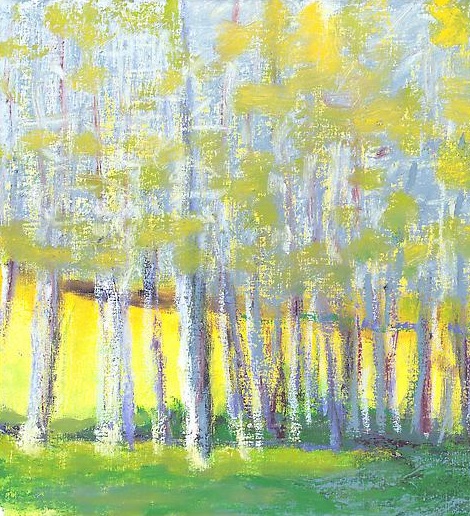

Growing Out of Dark Green, Wolf Kahn, oil on canvas

Popular and profound would be the grail. Easier said than done, but this is nice to hear:

From Tracey Emin’s unmade bed to Damien Hirst’s diamond-studded skull, the work of Britain’s avant garde artists has been lauded and derided down the years in almost equal measure. But now one of the country’s leading arts figures is to launch a ferocious attack on work that “rejoices in being incomprehensible to all but a few insiders”.

In a lecture on “the purpose of the arts today”, to be delivered today in London, Julian Spalding, a former director of three of Britain’s foremost museums and galleries, will say that the public purse should only fund work that is “both popular and profound, as truly great art is”. He will also criticise the supporting of works that appeal “to a self-congratulatory in-group”.

— The Guardian.

![Mosaic icon of the Virgin Episkepsis, late 13th century [Credit: Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens]](https://thedorseypost.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/madonna-and-Child-892x1024.jpg)