Worlds apart

From Proverbs and Commonplaces, Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY.

the painting life

From Proverbs and Commonplaces, Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY.

In painting, it can be hard to keep the cart behind the horse. For me, normally, paint comes first and everything else follows along behind. There are many ways to be clever and cerebral with a work of art, and most of them lead away from the subconscious drive to paint—a painting can too easily become a dutiful illustration of an idea. In my solo show in a couple weeks at Viridian Artists, entitled Polarities, I was drawn toward an idea of contraries as a basis for juxtaposing one kind of painting with another—or opposite principles within a single image. I arrived at the title and theme by looking at the work I’ve done over the past five years or so and seeing oppositions everywhere in the way I’d painted—in ways I hadn’t consciously registered while I was doing the work. At that point, I started working on some ideas for a few more paintings to complete the show. I was letting the idea of polarities serve as a basis for creating images that would fit, neatly or not, into the theme. For some people, this would be an occasion for applause, paintings that have “something to say”, work with a conceptual dimension, but I saw it as a Faustian bargain. Clever often means contrived. For the most part, though, the concepts here followed the work, sitting obediently in that cart securely behind the urge to paint.

I did one painting, Treaty: Jelly Bean Bullets, after coming up with my theme, though it took me weeks to arrive at the title. I kept stapling little notes at the crest of my easel’s middle strut, just above the upper edge of the painting, each note bearing a fresh, potential name. Armistice, no, Gun Control, no. Cease fire. Ugh. At first I was going to pair one of my candy jars with a jar full of empty Luger shell casings I found at Etsy, where they’re available in bulk as a craft supply for people making “steampunk jewelry.” Leave it to the Internet. I did a study or two of the empty shells and then at some point I saw how easily MORE

From Proverbs and Commonplaces, Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY.

From Proverbs and Commonplaces, Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY.

The novels of Herman Hesse were a hot item in the 60s, with their romanticism, their mix of Jungian psychology and Eastern mysticism and their hippie-friendly dreaminess. I read most of them when I was in high school. I loved the opening of Steppenwolf, the yearning of Harry Haller, the depressed, cerebral, central figure who takes a room in a clean, well-lighted boarding house and lingers on the stairs admiring the cleanliness and order of the home’s little windowed corners, all the attention devoted to middle-class comfort and restraint. He loved it because it was a levee against the tide of darker impulses and brooding that pulled him, throughout the book, toward a pyschologically liberating and dangerous life on the margins of respectability. Its tension between the passion for order and normalcy and the imaginative pull of the unpredictable is how the book fascinated me years ago when I read it. The other night, in an email, I read a quote from Mark Twain, sent from an acquaintance–“Be good and you will be lonesome.” It reminded me of Dostoyevsky’s Prince Myshkin, who was so good he simply uttered whatever he thought, without calculation, always telling the truth, or what appeared to be the truth to him, and the most fundamental truth he uttered was that “beauty will save the world.”

So I did a search for Prince Myshkin to refresh my memories about him and came across an out-of-print essay about him from Hesse, who was deeply influenced by Dostoevsky. To my surprise, it led me toward Hesse’s notion of polarity and how Myshkin himself was a figure who reconciled polarities by being rooted in something more fundamental than the world of opposites (in a Joseph Campbell kind of way). As Hesse puts it, about a scene where the prince is rejected by everyone around him:

On the one side society, the elegant worldly people, the rich, mighty, and conservative, on the other ferocious youth, inexorable, knowing nothing but rebellion and hatred for tradition, ruthless, dissolute, wild, MORE

The Metropolitan has joined in the trend championed by Google, Getty and the National Gallery and has uploaded 400,000 images of art for free public viewing, with resolutions fine enough to give you a “feel” for the surface texture. So quit taking pictures of permanent collections and just look while you’re there. As with Google’s art project, the photography is so good you can see much of what was only available by looking at the actual work, except for a sense of scale.

This is a great guide for buying good art that’s far more affordable than what gets traded at the air fairs in one particular city–Toronto, just a hop across the lake for us in Rochester. It’s a great point-by-point argument for buying art that represents a choice between a good painting and a new high-end flat-screen TV. That’s no Sophie’s Choice.

This is a great guide for buying good art that’s far more affordable than what gets traded at the air fairs in one particular city–Toronto, just a hop across the lake for us in Rochester. It’s a great point-by-point argument for buying art that represents a choice between a good painting and a new high-end flat-screen TV. That’s no Sophie’s Choice.

My friend Jim Mott came by a little while ago to discuss painting, “Tim’s Vermeer,” marriage, money, the uncanny behavior of birds, and an app he invented and created with the help of his partner, Bruce Campbell. A few days later, as a follow-up, he introduced me to a spot on the southern shore of Lake Ontario where you can see a dozen kinds of warbler in the course of an hour. They congregate there, biding their time before flying across the lake into Canada, maybe waiting for it to warm up enough to justify the effort. I photographed half a dozen warblers, a thrush I’d never seen before, a screech owl, a Lincoln sparrow and a couple catbirds. It was my first “birding” excursion, aside from climbing out of my TV-viewing chair to get a shot of a bird on our birdbath in the backyard.

The bird talk wasn’t completely unrelated to what he came to demonstrate: the game he made, called Dazzle, which is for sale on iTunes. It was designed with a couple disparate things in mind: the markings of a black and white warbler–which we saw in the woods a few days later–and the nautical camouflage used in World War I, called dazzle. Playing the game is simple: you try to rotate diagonal black-and-white squares to either match up colors for yourself or avoid matching them for your opponent. Points are assigned based on the number of matches. The level of simplicity is somewhere between Tic Tac Toe and Minesweeper. The game offers a virtual roll of dice to determine which square you have to rotate, and you can either play against the app or against another person.

“One of the things I like about it is that you can do something else intelligent, like have a conversation, while playing it,” he said.

Since Jim’s project, as an artist, is to take money out of the picture when it comes to art–traveling around the country and staying with people overnight in exchange for a painting of their surroundings–this app represents a very minor equivalent to a grant application or tenure for other artists. In other words, income not related to art sales. He created it to inspire the competitive urge, but also to give players a chance to get fascinated enough with the patterns they’re creating to quit caring who wins. That would be a nice principle to see applied to a lot of other activities. I bought it. It’s fun. Better yet, it’s like a donation to a Kickstarter campaign, without the Kickstarter.

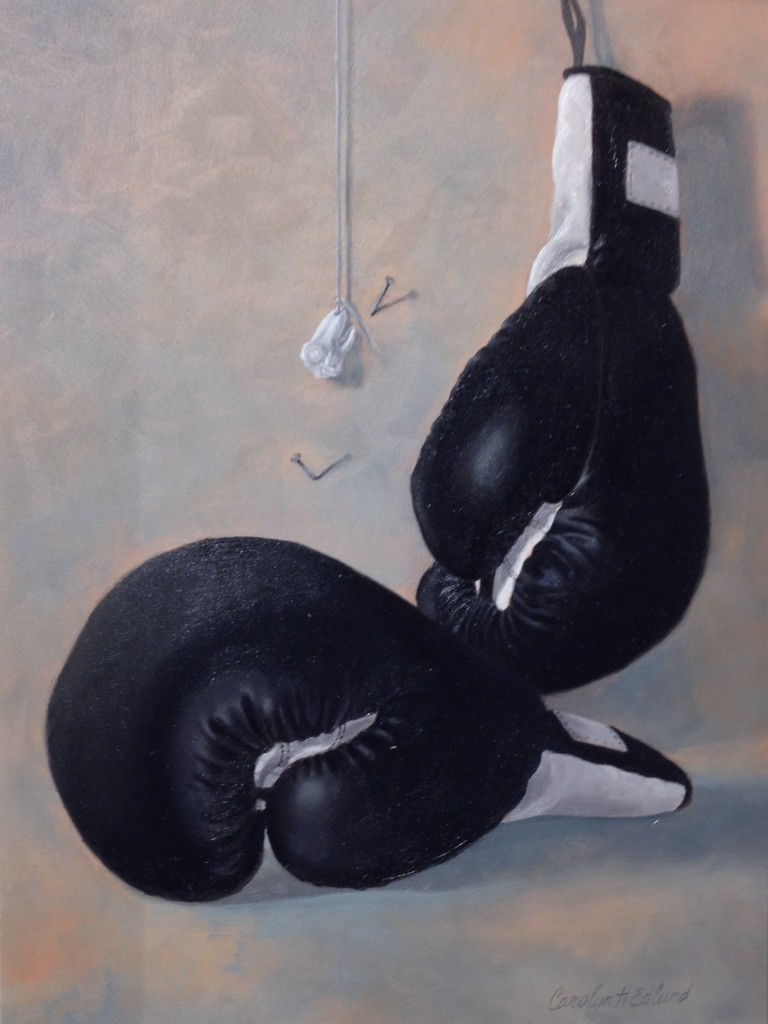

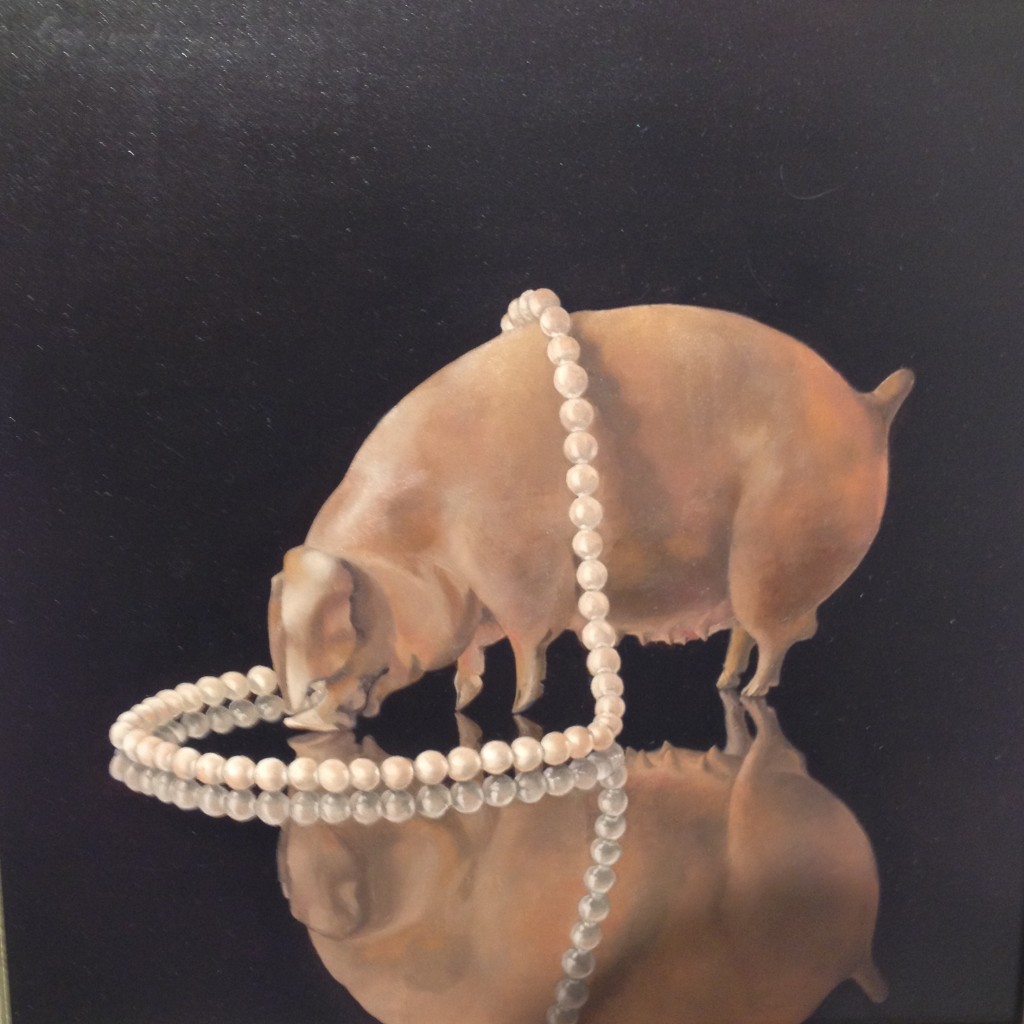

More from Oxford Gallery’s “Proverbs and Commonplaces” exhibit. Carolyn Edlund’s Fighting Tooth and Nail and Pearls to Swine.

More from Oxford Gallery’s “Proverbs and Commonplaces” exhibit. Carolyn Edlund’s Fighting Tooth and Nail and Pearls to Swine.

A first-ever collaboration is being staged at Ceres Gallery on May 24 at 4 p.m.: Vernita Nemec will perform in honor of under-recognized artists backed by the improvisations of Cat Casual’s William Benton, the singer and guitarist from Shilpa Ray and Her Happy Hookers. Vernita, our director at Viridian Artists, has presented her performance art as Vernita N’Cognita, in honor of unknown and uncelebrated artists, in the United States, Hungary, Japan, Ireland, Germany, Mexico and France, including performances at the Pompidou Museum in Paris and Documenta 13 in Kassel.

A first-ever collaboration is being staged at Ceres Gallery on May 24 at 4 p.m.: Vernita Nemec will perform in honor of under-recognized artists backed by the improvisations of Cat Casual’s William Benton, the singer and guitarist from Shilpa Ray and Her Happy Hookers. Vernita, our director at Viridian Artists, has presented her performance art as Vernita N’Cognita, in honor of unknown and uncelebrated artists, in the United States, Hungary, Japan, Ireland, Germany, Mexico and France, including performances at the Pompidou Museum in Paris and Documenta 13 in Kassel.

Cat Casual, a Queens instrumentalist and singer from Oklahoma, now with Shilpa Ray, has worked with a long list of luminaries: Nick Cave, Bonnie “Prince” Billy, Makoto Kawabata (Acid Mothers Temple), Steve Shelley (Sonic Youth), Steve Wynn (Dream Syndicate), Ivan Julian (The Foundations, Richard Hell and the Voidoids), and many others as well as sharing the stage with many legendary performers of the past and present. He is grooming his solo band, Cat Casual, for live shows in the near future. Most recently, he contributed original music for a production of Marius Von Mayenberg play The Ugly One which was performed at The Bridge Theatre.

Some throw-away thoughts that arose randomly in response to the Hyperallergic’s excellent reflections (and photography) of Kara Walker’s new 35-foot-tall installation. It’s a striking feline berm of polystyrene coated with 80 tons of sugar, configured as a Sphinx. It’s called A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, and it’s sitting inside Brooklyn’s deteriorating Domino Sugar Factory, now scheduled for demolition.

First, I thought of some Irish poetry:

1. . . . a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi/ Troubles my sight: a waste of desert sand;/A shape with lion body and the head of a man,/ . . . what rough beast, its hour come round at last,/ Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born? –W.B. Yeats

2. Thus having been put in mind of sphinxes that herald the apocalypse, or at least the end of factories as we know them, it struck me that if Subtlety were to start dating, after her performance in Williamsburg is up, her perfect match would be the equally apocalyptic Stay Puft Marshmallow Man, from Ghostbusters. They’re perfect for each other. They’re both enormous (weight issues would be off the table), made of sugar, very very white and they both bring intimations—at least for those with Yeats on the brain—of uprisings and/or end times. My only caveat for Stay Puft would be that he may be a big old sailor on leave and probably has seen more than his share of bad-ass ports, but the sweetness on offer here is only skin deep. Underneath she’s got a hard core of polystyrene. And, in turn, Subtlety should keep in mind that her hook-up is highly flammable. Aside from that, a one-in-a-million match.

3. Tired of bein’ lonely, tired of bein’ blue,

I wished I had some good man, to tell my troubles to

Seem like the whole world’s wrong, since my man’s been gone

I need a little sugar in my bowl,

I need a little hot dog between my roll. —Bessie Smith

4. Any cat lover, or simply cat observer, will recognize her pose as “elevator butt.” This is a term I discovered on YouTube after recognizing it from experience and trying to find a name for it. While being stroked affectionately on the back, or when ready for sex, a cat will raise its tail this way and expose itself. So this is a cat that’s either happy or about to be very very happy. It’s taking control of other cats in the time-honored way that women have taken control of men through the ages. The way sugar babies control sugar daddies. So, as if it weren’t enough to be an apocalyptic sphinx, this cat rules as they all do.

5. The last shall be first. An image explicitly honoring slaves by depicting a racial stereotype in a figure that represented, in Egypt, the fusion of god and humanity, would seem to indicate that Walker wants to celebrate how those who were last and lowest, a century and a half ago, now have the opportunity to be first and at the top of their chosen food chain. A visage that belonged to Aunt Jemima now adorns a figure that seems to demand worship, or obeisance, or at least some down-home adoration. The tips of a sweat-absorbent kerchief become the ears of a cool cat. The election of Barack Obama and the sale of Dr. Dre’s brand for $3 billion to Apple would be just two examples of how at least some members of a once enslaved race now can pretty much achieve anything they like in a way very few people can. There is a long list of others who have proven this to be true. (Some of us would like to reserve the right to wish for the old days when Dre was simply one of the most unique and minimalist DJs in hiphop who knew his way around an actual beat like few others.)

6. This turning of the tables, how the lowly can rise up into a position of power, the former slave becoming a master, put me in mind of Kurt Vonnegut’s Player Piano, of all things. It was a novel about a dystopia in which most work had been mechanized and automated. The machine is the ultimate slave yet the labor it offers increasingly displaces more and more human workers. What once simply served us, now usurps the role we once had and leaves us, like the children with their baskets of token sweets in Walker’s installation, wandering aimlessly and unemployed in the terrain it controls and harvests. The rule of technology would indeed be a sphinx worthy of W.B.’s poem, The Second Coming, though I doubt that Walker had this kind of reversal in mind, leaving aside the question of whether her image can stand as an emblem of it regardless of her intent.

7. Does artistic intent matter? Should it determine what effect a work has on a viewer? I like ideas that arise out of some visceral struggle with basic formal challenges. You want to pair something monochrome and cold and shiny against something soft and colorful and bright and you end up representing objects that enable you to do this and, maybe all those shapes cohere in a visual way. Sometimes, on top of that, you end up with another kind of coherence. A painting of, say, open diaper pins becomes an emblem of moral choice, a way of behaving, an outlook on life, once you step back and start thinking about it. None of this needs to be in the mind at the start of the process; only a desire to achieve a particular visual quality. But maybe an idea arises as you feed that impulsive, instinctive appetite to see certain colors and shapes appear on a field of white. Personally, I want to make paintings that have nothing to say, but evoke a world, a unity, a whole. If they imply more than I had in mind, fine. Yet I like Walker’s installation, as intentionally conceptual as it appears to be. It does all I ask: it makes me want to keep looking at it. I mean, who am I to say no to something that big? It makes me wonder if she had an idea of a sphinx lurking in the back of her mind for a long time and finally found the place to make it come alive, without any ideas associated with it, or did she come up with it only after being offered the space? Even better, did the sphinx not occur to her until she had sketched a hilly mound of abstract sugar, with its eskers and kames, and then she thought: hey, that could be the haunch of a cat! Better yet, a sphinx! And she went on from there. I’d love it if that were the case, because that for me is how art ought to come about. It starts as a subconscious pull, like love, towards certain instinctive physical choices, certain formal qualities, and in the effort to make a whole out of many disparate parts, something else happens. It all comes together somehow, and you’re surprised by what your mind has led you to do, even if it didn’t bother to enlighten you, along the way, about where you were headed.

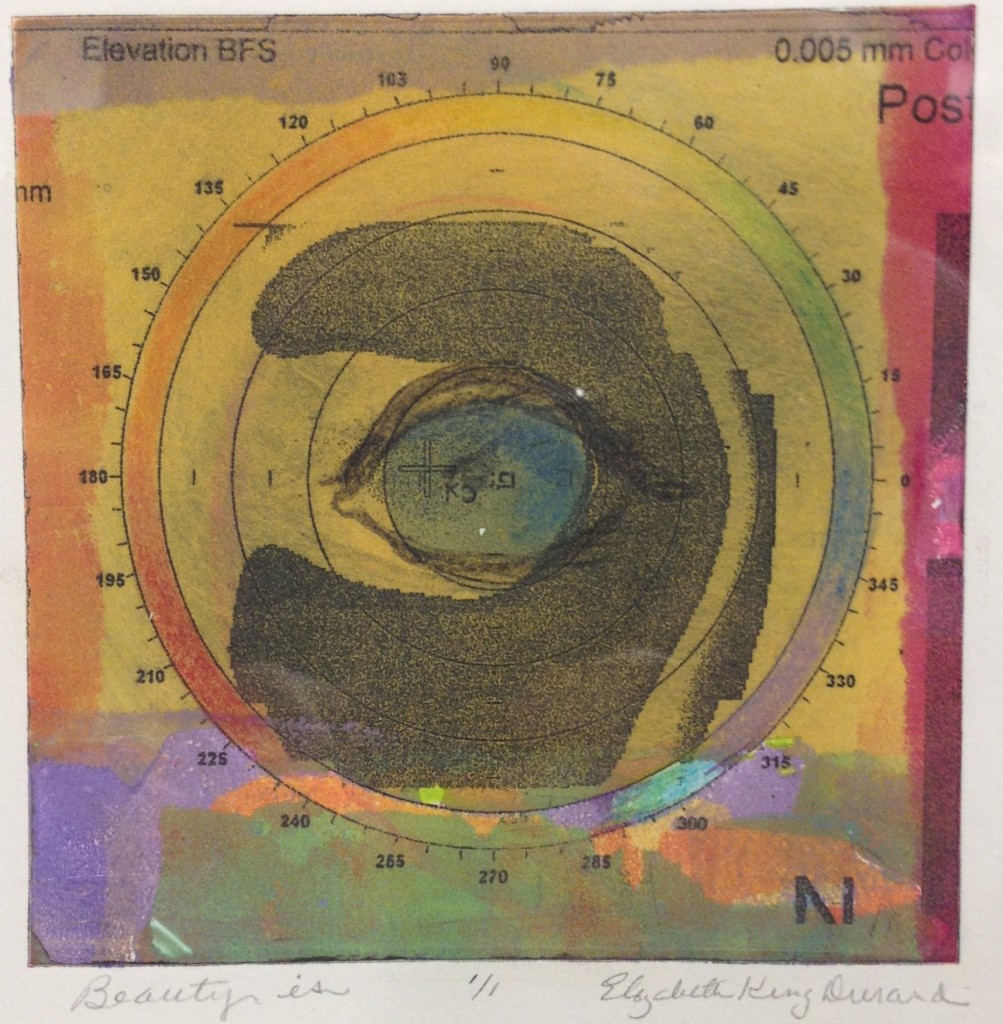

This wonderful print, Beauty is, by Elizabeth King Durand can be seen at a surprisingly colorful group show at Oxford Gallery, Proverbs and Commonplaces: all work based on sayings, a theme that presented itself to Jim Hall while he was reading a book about Bruegel. It’s a fascinating show and most of the work stands on its own, with the link to the saying offering an added layer of interest. King colored this monoprint by asking her technician for a copy of an X-ray taken for her cataract surgery. She was refused, but persisted with the surgeon who relented and printed it out for her. Her muted color sense is always full of elusive feeling.

This wonderful print, Beauty is, by Elizabeth King Durand can be seen at a surprisingly colorful group show at Oxford Gallery, Proverbs and Commonplaces: all work based on sayings, a theme that presented itself to Jim Hall while he was reading a book about Bruegel. It’s a fascinating show and most of the work stands on its own, with the link to the saying offering an added layer of interest. King colored this monoprint by asking her technician for a copy of an X-ray taken for her cataract surgery. She was refused, but persisted with the surgeon who relented and printed it out for her. Her muted color sense is always full of elusive feeling.

Great, funny piece from Huffington on how the Old Masters might have indulged in some obscurantist theorizing about their own work in order to be taken seriously, had they been contending with a postmodern academy. Sample from a contemporary Titian:

“Woman, goddess, subject, object and signifier: Venus activates both the Utopian and Dystopian spaces of the Venetian Palazzo. By inducing an affirmative valence of feminine/objective lucidity Venus poses a question: has our tendency to privatize desire further affirmed or disenfranchised her archetypal significance?”

The post concludes beautifully with:

“Life etches itself onto our faces as we grow older, showing our violence, excesses or kindnesses.”

– Rembrandt Van Rijn

That is what an actual artist’s statement sounds like…

And now, the studio equivalent of a Hint from Heloise. I was ready to toss out half a dozen brushes. I have always gone through them much faster than I should mostly because it seems the more I clean them, the gummier and more fly-away they get. (Is that a hair marketing metaphor? It’s synthetic sable, so . . .) I was at the utility sink washing them the usual way, linseed oil, turpentine, and then laundry soap, and because of a recent rug cleaning effort I thought of the granular Oxiclean in our laundry room cupboard. We have one of those tubs of it that reminds me of a gallon of Breyer’s ice cream, though I’ve found the nutritional content is a bit different. I dissolved some of the granules in a little jar and then stuck my brushes in it for a few hours. When I pulled them out, they were as close to new as I’ve ever seen a used brush get. It even dissolved the paint from the metal stem holding the hairs in place. My thought: all these years, and I’ve never tried this stuff before? I’m interested in seeing how the brushes work now when loaded with paint. The bottom two brushes in the photo above looked exactly like the top one before the Oxiclean. They’re soft now. This message was brought to you by me, not Oxiclean.

From Alain de Botton: “So he slowed things down and recommended we spend far longer looking at impressive things, even quite simple things. His own drawings showed the way.”

A new, very assured portrait from Sarah Burnes, in Oregon. Love how, as usual, she keeps the values bright, narrowing the range of light/dark, as well as restricting her palette to a very limited number of muted colors, with all that feeling concentrated in the slightly pinker tones around the mouth, one fingertip and an elbow. And her previous painting in the background feels completely integrated into the scene, as if the model is dreaming or remembering on earlier moment in that chair.

I’m eager to see Alan Gaynor’s solo show at Viridian Artists, starting this week: his shift toward the organic forms of these wilting flowers struck me as different from all of his previous work when I first saw them. All of his work is personal, but there’s a depth of feeling and vulnerability in the new work that’s arresting. His earlier shots of architecture reflected the passion he’s invested in four decades as a successful New York architect, yet the flowers are a shift toward something more intimate and unruly. He started taking this series while his wife was dying, and the gravity of his inspiration comes through in the beauty he finds in what are essentially leftover decorations, ready to be tossed out. His opening reception is tonight at Viridian. I talked to him a few days ago about his work:

Alan Gaynor: When I was in architecture school I took a photography course because I thought I didn’t know how to photograph, and I thought I should at least be able to take vacation pictures. I studied with a woman who gave us an assignment to take a roll of film, back in the day of wet developing. We’d shoot it and develop it on our own and come in with contact sheets. I did two rolls because I’m an overachiever. This was in 1969 maybe. I came back with my contact sheets and she looked at me in front of fifteen people in the class. She said Oh my God, do you know Eugene Atget’s work? I said, “I have no idea.” She said, “You should look it up. These are wonderful.” That was the beginning. I photographed all through college. I graduated from 35 mm to 4 x 5 and I shot 4 x 5 black-and-white film for years. I put it down since starting and growing this business was a double-time job. About twenty years ago I picked up the camera again and again started shooting black-and-white because I didn’t know how to process or print color. It was too difficult for me. I set up a dark room and started taking courses with people like John Sexton who was an apprentice to Ansel Adams for a long while. With some people who were very large names and from every one of those people I learned something. I started shooting buildings and cityscapes. Then I got interested. My son is seventeen and he was a subway freak since he was four years old. He had a real wanderlust as a child. I began to appreciate the subways in a way I hadn’t before. I stopped and started looking at them. I had to get a pass from the MTA and set my camera up, but I still got my chops broken by the police but that was OK. They’d let me finish the shot and that’s all I cared about. I had a pass but you don’t want to argue with them. I’d beg them to let me finish the shot. I shot some landscapes for a while. I switched to digital.

DD: That would make color possible.

AG: It made color easy but black-and-white difficult until I learned to convert to black-and-white. I love Indian architecture, Islamic architecture. I started doing these panoramas from mid-level up in buildings. Those were taken knowing exactly how they were printed. A city you experience as a layering of buildings not individual architecture. The layering of one thing on top of another on top of another on top of another. Those panoramas were designed to express that. Then during this period my wife got very, very ill.

DD: I think that’s a big factor in what’s going on now in your work.

AG: It’s a very big factor. The first flower shot I took were tulips I bought for her. They were her favorite flower. As they were dying, she was dying. After that I started photographing half-dead or three-quarter-dead flowers sort of as a tribute to her but also to work it out as a photographer.

DD: Those are fascinating. The first of your work I saw were the panoramas that seemed very controlled, not that these aren’t controlled, but they’re opposite in the quality of line, the color . . . it’s all controlled in the way you frame it. You’re setting it up no matter what you shoot.

AG: The thing about photography, it’s all about framing. I take very few photographs. It’s extremely deliberate. The camera is something I use to compose; it’s not random. It’s why I don’t do street photography. I don’t do people. I look at someone like Walker Evans who did both that and the sort of things I do. He did lots of different things. I’m only interested in the composed; not the accidental or photographing people doing wonderful things or funny things. Not that I don’t like people, it isn’t what I’m interested in photographically.

DD: Gary Winogrand, for example.

AG: He’s a very fine photographer. But it isn’t random. Everything informs what you do. My being an architect informs what I do even when I’m photographing flowers.

DD: With the flowers, the whole situation with your wife is there in those pictures and other people wouldn’t take them that way.

AG: They wouldn’t see the beauty in dying flowers. I don’t know who else shoots dying flowers; not that I was looking to do something nobody else was doing. Part of the democratization that the camera gives is that anybody can click a button but not everyone can see or compose; not everyone sees the shot in front of them. It isn’t a matter of putting the camera on automatic and walking down the street.

DD: Describe for me how you do the flowers.

AG: It’s very simple. I wait until the flowers get to a particular state and then use a relatively diffuse overhead light only. I shoot against a seamless gray background most of the time. I started out using a Canon 5D Mark II graduated to a Hasselblad with a macro lens. It’s a lovely piece of machinery. I have an Arca Swiss view camera with a digital back. My camera of choice is the Hasselblad. I have an older one that will take a 39 megapixel back with a proper mount. Hasselblad lenses are wonderful. It’s certainly not a consumer camera. When I shoot architecture with my Canon I go nuts trying to correct the distortions. The lens distortion. Canon lenses are wonderful but it’s not a Hasselblad lens or a Leica lens.

DD: You get curving lines?

AG: Yes. Barrel distortion. The Haselblad lens is much higher quality. The panoramas are done on a 6 x 9 view camera with Rodenstock or Schneider view camera lenses, with a sliding back that allows me to stitch together three or four shots. Those are wonderful lenses. If I set the view camera right I don’t get distortion. It’s a lot of the work, and it has taken me years to learn. There is a lot of work I couldn’t do. If you took me to a photo studio, I would not be able to shoot products.

DD: That has a lot to do with lighting.

AG: Yes, and I use very rudimentary lighting.

DD: Are you reflecting off a white surface?

AG: No, it’s direct light. It’s being filtered through a shade-like material. I shoot on my dining room table, frankly.

DD: Do you use a full spectrum bulb?

AG: No. In Photoshop the gray is gray, or some other color I want. A lot of it is post-production.

DD: You have to get depth of field right though.

AG: You can do focus stacking. With RAW files, it allows you—I haven’t done it yet—but it allows you to stack focus. You shoot ten RAW files, each one is focused at a different depth.

DD: Like HDR, for exposure.

AG: Yes. A lot of what I do is post-production.

DD: When you pick these flowers, are you picking them specifically for the photographs?

AG: I have a friend who works for a commercial florist and I pick up her dead flowers. After an event, I get the flowers.

DD: That goes with the whole feel of what you’re doing with the shots. They’re almost like found objects.

AG: Either I take them or they go into the trash, or the compost if we’re being ecologically responsible. I feel like I’m getting to the end of the flowers, but I don’t know. I’m so involved in the architectural business, with the move to the new location, I’m not sure.

DD: How long has your firm been around?

AG: This is our fortieth year. In ’75 I decided I needed to be in Manhattan. I was in Brooklyn at the time. For $85 a month I had a full floor of a brownstone.

DD: That’s amazing.

“Where any view of Money exists Art cannot be carried on . . .”

–William Blake’s annotations to the Laocoon

I grew up in a world in which what artists aspired to was to be able to go to their studio, make art, sell a work occasionally, so they can buy some Wheaties, and some records, and listen to records, and make art, and eat Wheaties. And that was their goal: stay away from the straight world, and stay away from the university, and live their lives.

When I was invited to apply for membership at Viridian Artists in 2011, I didn’t first take my samples around to regular commercial galleries in New York City to see if any would represent me for no charge other than, well, half the revenue of anything they sold. Fifty percent commissions didn’t bother me. That’s standard. A gallery has to eat too. At the time, I didn’t think I had the track record to have, say, a Hirschl & Adler take me on—wishful thinking even now, no doubt—yet I still deliberated a while before committing myself to $7,500 for two and a half years of participation and a solo show. (That $7,500 is only the beginning, as I’ll describe shortly.) Once I joined, my first task was to help the gallery move from its old space on W. 25th St. to its current spot on W. 28th because it was already in need of a less expensive venue for its members—as real estate continues to get pricier in New York City. By “help the gallery move” I mean I carried a lot of stuff down several floors and crammed it into the bed of Rush Whitacre’s pickup, at which point we drove it a few blocks north and unloaded it. Putting in the labor was part of the deal. Members agree to work at the gallery for many hours every year, which is a way of supporting it, but also, for those of us who live hundreds of miles away, another additional cost and benefit. The cost you measure in dollars: gas, lodging, parking, beer, Philly cheesesteaks, Thruway tolls, rides through the Lincoln Tunnel, subway fare, and admission to museums. (Some of that isn’t really a requirement of membership but an unavoidable consequence of coming down for a visit.) The benefits of hanging around Manhattan are less tangible, but just as real, and I will get to those down below.

Now, three years later, I face the choice of renewing my full membership MORE

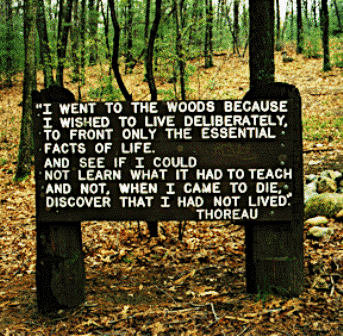

After a couple years in the working world, when I decided to return to college and enter graduate school to study literature in the 70s, I read Walden. It has always struck me as an essential book for anyone attempting to leave behind commonplace assumptions—the sort of wisdom that advises you to focus on earning money, gaining power, being well-known, contributing to society, and so on—and simply spend a couple years doing nothing but being aware of life. (Of course, if you get married and have children, all the commonplace wisdom kicks into gear, which is what happened to me.) Granted, Thoreau found a more direct way to “be aware of life” than by studying what people had written about life, yet Walden is full of quotes, so I imagine his two years spent doing what most people would consider nothing was occupied with a fair amount of reading. Hence, Walden is a reasonable book to read before driving to Illinois to study Melville, instead. (I was still thinking fondly of you, though, Henry.)

After a couple years in the working world, when I decided to return to college and enter graduate school to study literature in the 70s, I read Walden. It has always struck me as an essential book for anyone attempting to leave behind commonplace assumptions—the sort of wisdom that advises you to focus on earning money, gaining power, being well-known, contributing to society, and so on—and simply spend a couple years doing nothing but being aware of life. (Of course, if you get married and have children, all the commonplace wisdom kicks into gear, which is what happened to me.) Granted, Thoreau found a more direct way to “be aware of life” than by studying what people had written about life, yet Walden is full of quotes, so I imagine his two years spent doing what most people would consider nothing was occupied with a fair amount of reading. Hence, Walden is a reasonable book to read before driving to Illinois to study Melville, instead. (I was still thinking fondly of you, though, Henry.)

I’ve always been pleased by the fact that, early on, Thoreau shared his budget with his reader. It wasn’t really a budget, but closer to the equivalent of a receipt from Home Depot, detailing how much he spent on the little house (a room more than a house) he built for himself at the edge of the pond. I don’t know how much, in current terms, a dollar was worth in 1850, back before the Civil War began, but inflation aside, his investment sounds pretty reasonable:

Boards, ………………………… $8.03½, mostly shanty boards.

Refuse shingles for roof and sides, 4.00

Laths, ………………………….. 1.25

Two second-hand windows with glass, … 2.43

One thousand old bricks, …………… 4.00

Two casks of lime, ……………….. 2.40 That was high.

Hair, …………………………… 0.31 More than I needed.

Mantle-tree iron, ………………… 0.15

Nails, ………………………….. 3.90

Hinges and screws, ……………….. 0.14

Latch, ………………………….. 0.10

Chalk, ………………………….. 0.01

Transportation, ………………….. 1.40 I carried a good part on my back.

In all, …………………… $28.12½

These are all the materials, excepting the timber, stones, and sand, which I claimed by squatter’s right. I have also a small woodshed adjoining, made chiefly of the stuff which was left after building the house.

I intend to build me a house which will surpass any on the main street in Concord in grandeur and luxury, as soon as it pleases me as much and will cost me no more than my present one.

A house for $28. I think you might have gotten a foreclosed underwater house at auction in Detroit for that in 2009, but I don’t think I could build even a Lego version of Henry David’s home on that budget now. I’m not sure it would pay for a movie for two, if you require popcorn. MORE