Archive Page 9

March 10th, 2020 by dave dorsey

JERRY: I have to go meet Nina. Want to come up to her loft, check out her paintings?

GEORGE: I don’t get art.

JERRY: There’s nothing to get.

GEORGE: Well, it always has to be explained to me, and then I have to have

someone explain the explanation.

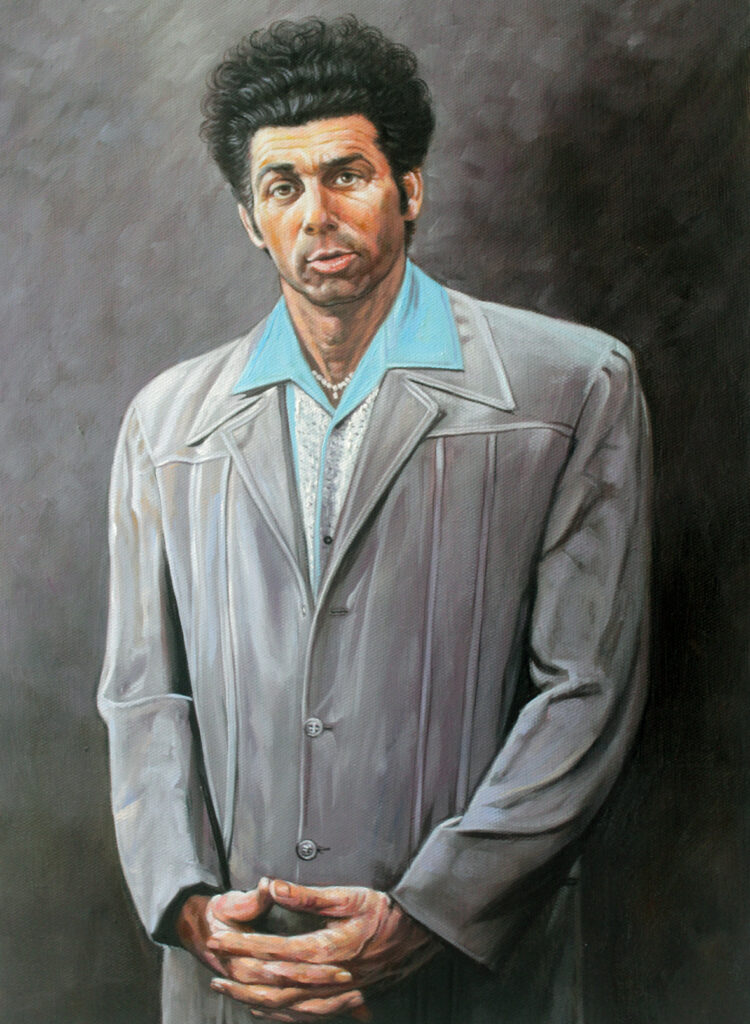

JERRY: She does a lot of abstract stuff. In fact she’s painting Kramer right now.

GEORGE: What for?

JERRY: She sees something in him.

GEORGE: So do I, but I wouldn’t hang it on a wall.

In

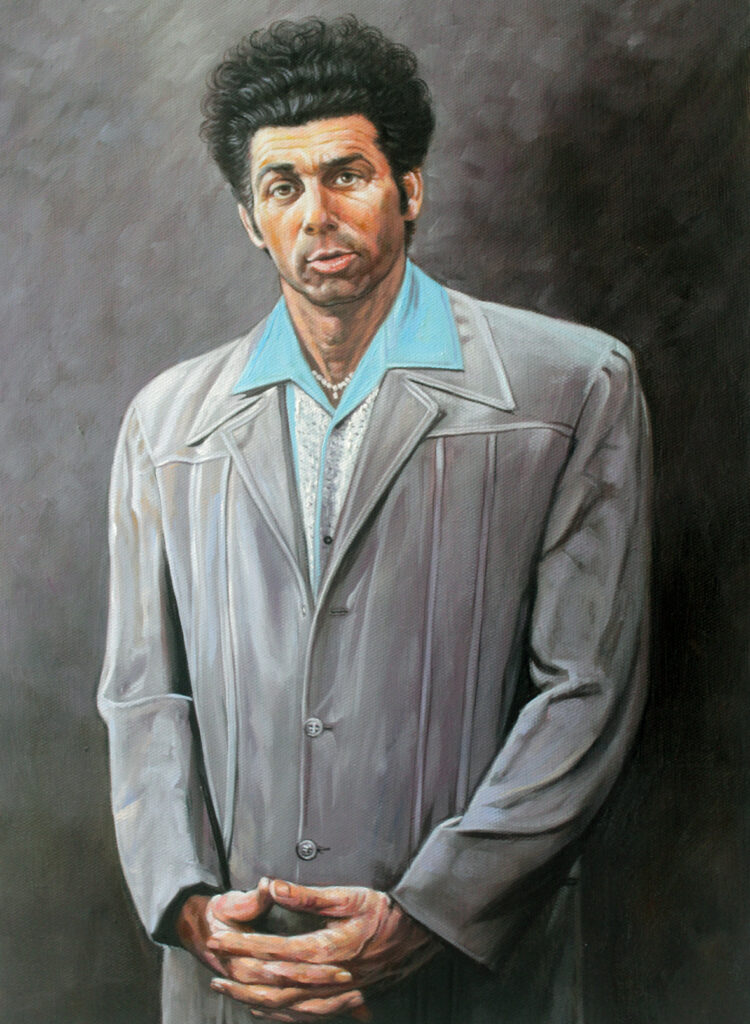

“The Letter,” the 37th episode of Seinfield, Jerry’s girlfriend, played by Catherine Keener, is painting a portrait of

Kramer, which inspires this conversation. Did anyone have to explain visual art before 1850 or so? Did explanations become more important than the creative work itself at some point mid-20th century? Jerry is right: there’s plenty happening in a great painting, but there’s nothing to get in the greatest of them, at least in the sense of an explanation.

March 7th, 2020 by dave dorsey

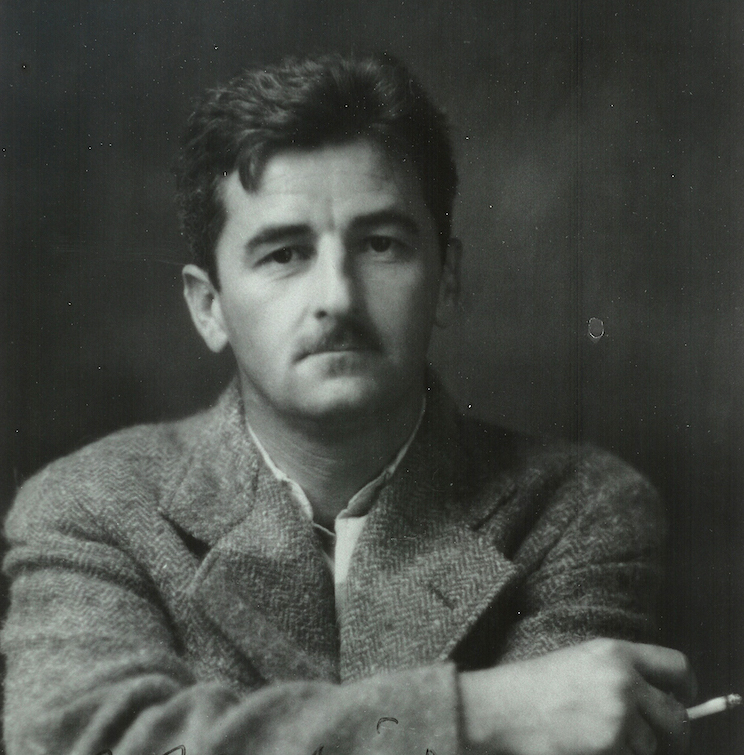

“I write only when inspiration strikes. Fortunately it strikes every day at 9 a.m. sharp.”

That quote has been attributed mostly to Faulkner but also to a number of other writers. It summarizes pretty much what it requires to be professional at anything: habitual hard work. I like the quote because that’s exactly the time I usually sit down at the easel, and it’s when I have the most energy and am also the most critical of what I’ve already done, partly because the sun rises and shines through a window behind me, often striking the canvas directly. There’s no escape from that intensity of sunlight: God’s flashlight, as Larry Miller put it in a slightly different context, though the feeling is the same. Despair and shame at everything so manifestly wrong that felt so right at the time. So 9:05 is when inspiration really strikes. It’s when you ignore everything going on inside you–the sudden urge to remodel the basement, the desire to shovel snow, the ease with which you can now contemplate the emotional safety of bank robbery compared with the struggle of painting–and you pick up the brush. Or the old shirt you use to wipe away a few square inches of still-tacky paint that represent five hours of sub-par effort–and you make merely acceptable whatever looked perfect yesterday and then, around 11 a.m, you actually start spreading paint on canvas in places you haven’t yet defiled. Around 3 p.m. you think, “Damn, I’m good.” Until inspiration strikes again at 9 a.m.

February 11th, 2020 by dave dorsey

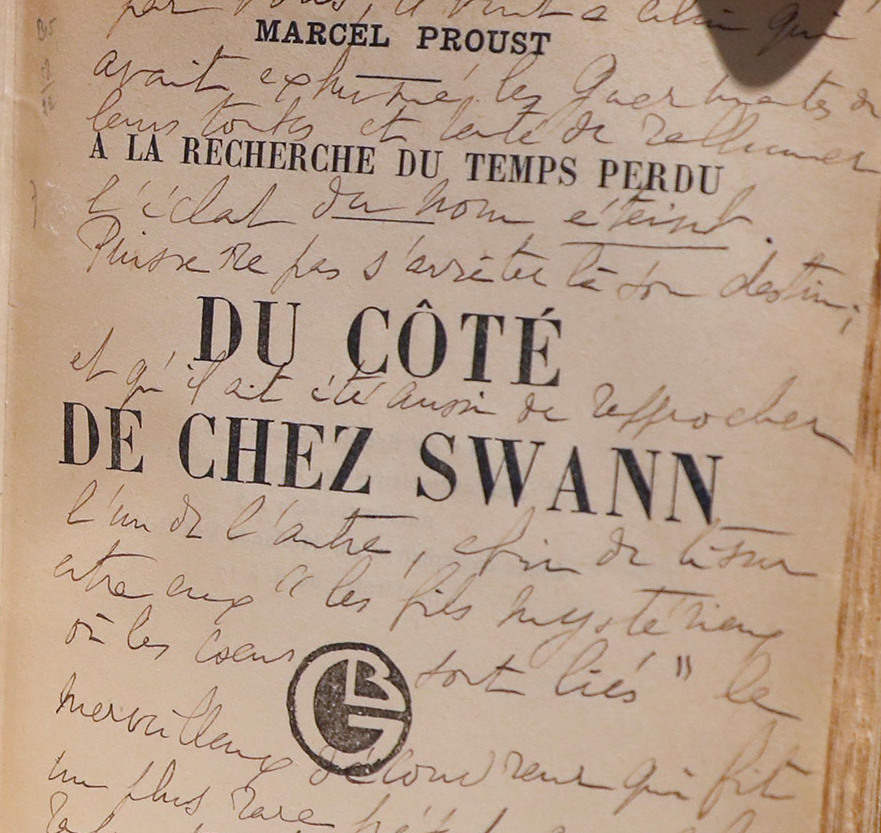

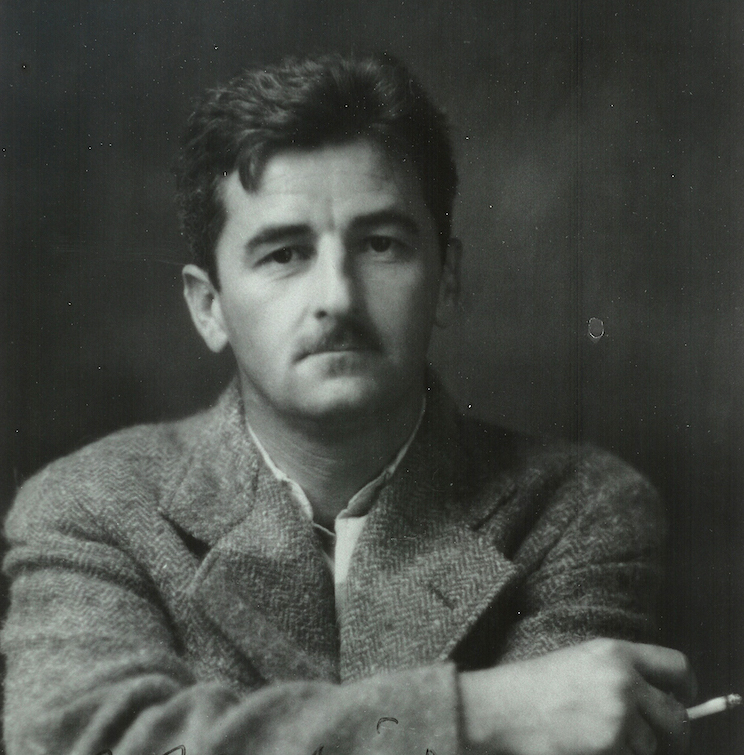

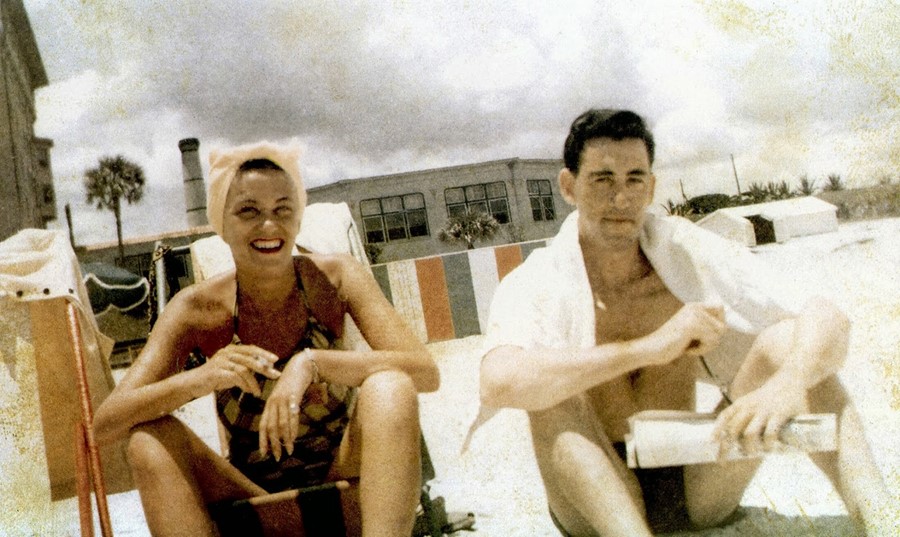

Sans bananafish, J.D. Salinger with his sister, Doris

Some flava in ya ear (if you read this aloud.) I mean, seriously, a lot of flava. J.D. Salinger’s recipe for popcorn (I hope the measure for the popcorn itself represents the amount of unpopped kernels). This was a small contribution to the exhibit of personal items from his archives at the New York Public Library. The salutary effect of the exhibit was to bring into relief how happy, if not blissful, Salinger’s life was in Cornish. He liked him some Hitchcock. He loved spending time with his grandkids. He read books about spies and kept the Associated Press Stylebook on a shelf in his bedroom. He could write letters like nobody’s business. And, OK, he was a little weird, but the weirdness was at the heart of how great he was, and, besides, aren’t we all, a little? It was cool to learn that had a Chevy Blazer, from way back close to when GM started to market them, to haul the firewood he cut.

For 1/2 cup of popcorn:

6 tsps sea salt

2 tsps paprika

1 tsp. dry mustard

1/2 tsp garlic powder

1/2 tsp celery powder

1/2 tsp thyme

1/2 tsp marjoram

1/2 tsp curry

1/2 tsp dill powder

February 8th, 2020 by dave dorsey

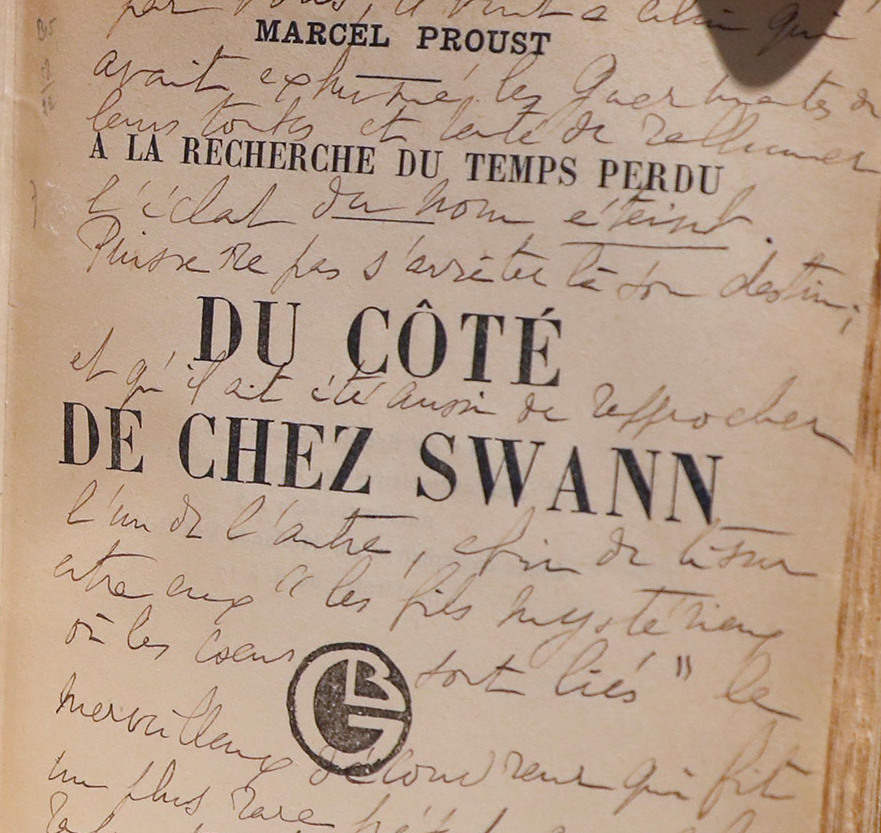

An orginal edition of Swann’s Way from Proust archives. Photo by Getty

Why art runs in parallel to science as a way of discovering what science can’t plumb, sort of the corrolary of chemical elements in the structure of human subjectivity, the human heart, from Swann’s Way:

When, after that first evening at the Verdurins’, he had had the little phrase played over to him again, and had sought to disentangle from his confused impressions how it was that, like a perfume or a caress, it swept over and enveloped him, he had observed that it was to the closeness of the intervals between the five notes which composed it and to the constant repetition of two of them that was due that impression of a frigid, a contracted sweetness; but in reality he knew that he was basing this conclusion not upon the phrase itself, but merely upon certain equivalents, substituted (for his mind’s convenience) for the mysterious entity of which he had become aware, before ever he knew the Verdurins, at that earlier party, when for the first time he had heard the sonata played. He knew that his memory of the piano falsified still further the perspective in which he saw the music, that the field open to the musician is not a miserable stave of seven notes, but an immeasurable keyboard (still, almost all of it, unknown), on which, here and there only, separated by the gross darkness of its unexplored tracts, some few among the millions of keys, keys of tenderness, of passion, of courage, of serenity, which compose it, each one differing from all the rest as one universe differs from another, have been discovered by certain great artists who do us the service, when they awaken in us the emotion corresponding to the theme which they have found, of shewing us what richness, what variety lies hidden, unknown to us, in that great black impenetrable night, discouraging exploration, of our soul, which we have been content to regard as valueless and waste and void. Vinteuil had been one of those musicians. In his little phrase, albeit it presented to the mind’s eye a clouded surface, there was contained, one felt, a matter so consistent, so explicit, to which the phrase gave so new, so original a force, that those who had once heard it preserved the memory of it in the treasure-chamber of their minds. Swann would repair to it as to a conception of love and happiness, of which at once he knew as well in what respects it was peculiar as he would know of the Princesse de Clèves, or of René, should either of those titles occur to him. Even when he was not thinking of the little phrase, it existed, latent, in his mind, in the same way as certain other conceptions without material equivalent, such as our notions of light, of sound, of perspective, of bodily desire, the rich possessions wherewith our inner temple is diversified and adorned. Perhaps we shall lose them, perhaps they will be obliterated, if we return to nothing in the dust. But so long as we are alive, we can no more bring ourselves to a state in which we shall not have known them than we can with regard to any material object, than we can, for example, doubt the luminosity of a lamp that has just been lighted, in view of the changed aspect of everything in the room, from which has vanished even the memory of the darkness. In that way Vinteuil’s phrase, like some theme, say, in Tristan, which represents to us also a certain accretion of sentiment, has espoused our mortal state, had endued a vesture of humanity that was affecting enough. Its destiny was linked, for the future, with that of the human soul, of which it was one of the special, the most distinctive ornaments. Perhaps it is not-being that is the true state, and all our dream of life is without existence; but, if so, we feel that it must be that these phrases of music, these conceptions which exist in relation to our dream, are nothing either. We shall perish, but we have for our hostages these divine captives who shall follow and share our fate. And death in their company is something less bitter, less inglorious, perhaps even less certain.

February 5th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Peggie Blizard. Pink Flowers in Water, Oil on Panel, 30 x 24

I’m partial to jars. I love the way a Ball jar’s particular utility lends character to its shape and surface, and how everything flows from its usefulness, its handle, the gemlike refractions of the embossed logo, and especially the glass threads for the lid around the lip. Along with its generally humble demeanor. When I walked into the little room where Peggie Blizard’s solo show was on view at George Billis (yet another discovery for me there), my immediate reaction was that I wished I had done the paintings myself. (It’s the way I usually react to work I love.) Her translucently blue and colorless, transparent Ball jars have a squat, almost muscular repose that give weight to the dense delicacy of her seemingly random bouquets, loading the center of the canvas with a gorgeous and rigorously rendered entanglement of color and line. Each painting is an improvisation within the same format: the rampant complexity of flowers thrust into the smooth and simple and uniform tones of the glass, echoed by the slight variations in sunlight on the uniform wall behind the jar, which serve to unify the multiplicity of shapes and tones, centering them, concentrating them into a static explosion. With ingenuity, she has stuffed blossoms down into the jar, mingling with the stems, to extend and push her cluster of lustrous color down to the bottom of the panel. The tones are conveyed with passionate accuracy, and the light brings to mind Janet Fish’s sunny still lifes at their brightest. Her show ends in a few days.

February 2nd, 2020 by dave dorsey

Christopher Burke’s work hanging in back at George Billis in Chelsea. Billis is at work on the computer, at the right.

Though three other artists at George Billis Gallery in Chelsea were having solo shows in the temporary space Billis had arranged to use next door to permanent location (undergoing renovation), he still managed to have maybe eight or nine paintings by Christopher Burke hanging in the office hallway. It was the first time I’ve been able to see the actual paintings, having followed him on Instagram with great interest. There’s a subset of artists I follow on Instagram who, like Burke, are working to find ways to make images representationally persuasive but also effectively abstract in one way or another, none of them much like any of the others: Burke, Joshua Huyser, Jessica Brilli, Harriett Porter, Mark Tennant, James Neil Hollinsworth, Harry Stooshinoff, Mitchell Johnson and many others. Each of them is representational and abstract in different ways.

Burke’s work holds up no matter how close you get to it. This is not something I can say about a number of otherwise amazing painters. (Walton Ford’s paintings are breathtaking , but up close, when you get near the actual work, the marks seem expedient and for some reason, disappointing, though it’s hard to say in what way. In a discussion with my friend Rick Harrington, now living and painting in Oregon, I learned that he’d had the same reaction. The images are stunning; the paint itself not so much, though neither of us could say why it mattered in terms of the quality of what he does. And Ford would hardly care about our disappointments.) All of which is an awkward, roundabout way to say Christopher Burke’s paint holds up from any distance, something I wanted to confirm by paying a visit to Billis on my short trip to Manhattan–having been unable to get to Burke’s show here late last year. His choice of subject is crucial to what he’s doing. The images, both his carefully composed portions of roof and sky as well as his drone-like perspectives of flood plains, offer him that perfect balance between abstraction and precise realism. What’s marvelous is how much feeling Burke can invest in images so minimal and geometric. Visually, Sheeler was up to something similar in Conversation–Sky and Earth, but Burke’s images are beautiful in a more vulnerable way, partly because of their almost Japanese aura of loneliness and emptiness. These humble corners of the sky keep company with an empty, silent billboard jutting up into view, an abandoned water tower gathering shadow, the dusk soon to make everything in these paintings invisible. No one’s around. The power lines sag. Birds congregate somewhere else. Everything is rendered with absolute care and rigor and even tenderness; everything is just as it needs to be. There’s nothing lacking in the painting nor in the world Burke just barely reveals to you.

January 30th, 2020 by dave dorsey

View of Norra Djurgardsstaden reurbanization project around Gasklockan 1 and 2, oil on linen, 33″ x 77″

On my brief visit to New York City, to spend a few hours at the New York Public Library’s J.D. Salinger exhibit a few days before its final weekend, I caught the new installation of work from three artists at George Billis Gallery. It was the only exhibit of new painting I was able to see, because I timed my visit on the worst possible day—between exhibitions at almost all the galleries in Chelsea. Billis had a leg up on all the others and was already prepared for the following night’s opening.

I was the only visitor at the time, with Billis himself clicking away on the computer in back, and Todd Gordon—the painter whose work had been hung in the main gallery space—standing at the window on a call with his wife who was arriving at the airport, having flown in from Sweden with the kids. I didn’t realize he was the exhibiting artist until I’d toured the entire gallery and wandered back to ask him, in my own charming way, where to find a rest room. I’m relieved to report that I never got to my question, because he introduced himself, and we launched into a discussion of the state of the art world at the moment—a delightful series of agreements about almost everything. He was intense, making his points without belaboring them, as I was more likely to do, but amiable and generous in his eagerness to endorse some other contemporary painters whose work would be on view at galleries he directed me to visit.

He’s tall, fit, with the bearing and aura of a guitarist who would prefer to be considered alternative, a good sense of humor, quick to pick up on the slightest irony and add his terse two cents. He had the quality of attention, the alert bearing, of someone who is out in the field, engaged in the hunt, a fellow soldier, not just someone making observations about the battle from a safe distance. I had the sense that, he was doing what we’re all doing: trying to puzzle out, not just from year to year, but from minute to minute, whether or not genuine art can rise up and float over the slippery, unreliable ocean of wealth that grants painters an income and makes a few rich, for better or worse. It’s an experiment with as many possible outcomes—and few, if any, are repeatable—as there are painters.

His painterly landscapes and cityscapes, many similar to urban scenes that he has been doing for quite a while, were compellingly intricate and fresh. In addition, he’d included some more traditionally rustic wooded settings, all of them just as unsentimental and exacting as the city scenes. He works from direct observation, and though he describes himself as a Brooklyn artist on his website, he resides in Sweden and paints both there and in Italy. Aside from his considerable skills at capturing tone and value and conveying the volume of what he’s depicting, what I liked most was the panoramic aspect ratio, as it were, of the work—extremely wide and shallow, like a sideways scroll. It gave me the sense of the proliferation of the world, the seemingly superfluous expanse of natural life and fabricated objects. It’s a meditation on the plenitude of every big and little thing out there—mundane, wonderfully ordinary, and suited to whatever it happens to be doing, or not doing, wherever it stands in the scene.

“This is great work,” I said.

“I’ve got more. I’ve got enough to fill the other two rooms,” he said, smiling ruefully, motioning toward the other smaller solo shows with a slight air of frustration.

It was a nice space, on an upper floor with plenty of natural light, and though I liked the way Billis was able to organize three solo shows simultaneously, I could sympathize with Gordon’s eagerness to get as much exposure as possible, if he had so much other new work not on view. We were actually occupying temporary quarters, next door to George Billis’s permanent gallery, which was undergoing a reconstruction. This space was on loan to him for the current shows.

I asked Gordon what it was like to live in Sweden.

MORE

January 27th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Jeremy Duncan, Ford Pickup, gouache on paper. Instagram

January 24th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Marie Therese Walter and Maya

The desires of the heart are as crooked as corkscrews.

—-W.H. Auden

1

When I was visiting the L.A. County Museum of Art a year ago, I came across the final print from Picasso’s Vollard Suite in Fantasies and Fairy Tales, a small, beautifully curated selection of graphic work by various artists from around the early 20th century. It immediately changed my emotional response to Picasso as a visual artist. It struck me as fine in a way so much of his work isn’t—there was a subservient care for the image itself that seems largely absent from so much of Picasso’s work. Usually, he forces his images to work, creating an image that feels kinetic and improvisational, without many pains taken for any other quality. I’d seen reproductions of the print, but never before actually noticed the self-effacing craftsmanship that went into the dreamy light that illuminates his figures in the Vollard print. By establishing that diffuse stage lighting, from below the players, with the light source hidden off to the left at ground level, he bathes the  last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order Picasso Prints: The Vollard Suite, and to keep returning to it through the rest of 2019, off and on studying what Picasso had done in it, leading me to conclude that these prints may have been his most original and personal (those two adjectives are mutually dependent) contribution to Western art. Much of the suite may not rank as his finest work on technical grounds, nor his most beautiful, nor his best on many different levels, but they are what I would save of everything he did, if I had to pick one achievement of his to take to a desert isle. I suspect no one else in the history of art has done what Picasso did here: it’s almost as if he is undercutting and cancelling everything he’s accomplishing as he achieves it, fusing the act of creation and destruction and creating images of great beauty in the process. All of this was in the service of the brief stirrings of a moral self-doubt he managed to suppress in himself once he’d painted Guernica, which served as a sort of footnote to this series of prints.

last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order Picasso Prints: The Vollard Suite, and to keep returning to it through the rest of 2019, off and on studying what Picasso had done in it, leading me to conclude that these prints may have been his most original and personal (those two adjectives are mutually dependent) contribution to Western art. Much of the suite may not rank as his finest work on technical grounds, nor his most beautiful, nor his best on many different levels, but they are what I would save of everything he did, if I had to pick one achievement of his to take to a desert isle. I suspect no one else in the history of art has done what Picasso did here: it’s almost as if he is undercutting and cancelling everything he’s accomplishing as he achieves it, fusing the act of creation and destruction and creating images of great beauty in the process. All of this was in the service of the brief stirrings of a moral self-doubt he managed to suppress in himself once he’d painted Guernica, which served as a sort of footnote to this series of prints.

2

The Vollard Suite isn’t what I like most from Picasso, which have to be his portraits of various lovers, wives and children, and the often beautifully lit paintings of massive, neoclassical women. Some of his abstracted figures are powerful, but most of his work as he was inventing Cubism with Braque seems monotonous in retrospect. What makes the Vollard Suite unique is also what makes it ahistorical, though the series is clearly of its time: modern in the sense of being thoroughly anchored in surrealism, with a glance or two back toward Cubism. It’s also postmodern in its many self-referential subversions of its own beauty. Yet it’s mostly neoclassical in spirit, tone and ambition—to an almost reactionary degree—though his masterful lines morph into something rich and strange before he’s finished. These prints hint at a yearning for innocence through the intensity of their plea for lucidity, for an impossible way out of the blind passions that invest them with life. They yearn for goodness and wisdom, and even offer the glimpse of an ambiguous spiritual harbor, which remains just out of reach. MORE

January 19th, 2020 by dave dorsey

A sample of Leo Ragno’s portraiture, from Instagram

January 16th, 2020 by dave dorsey

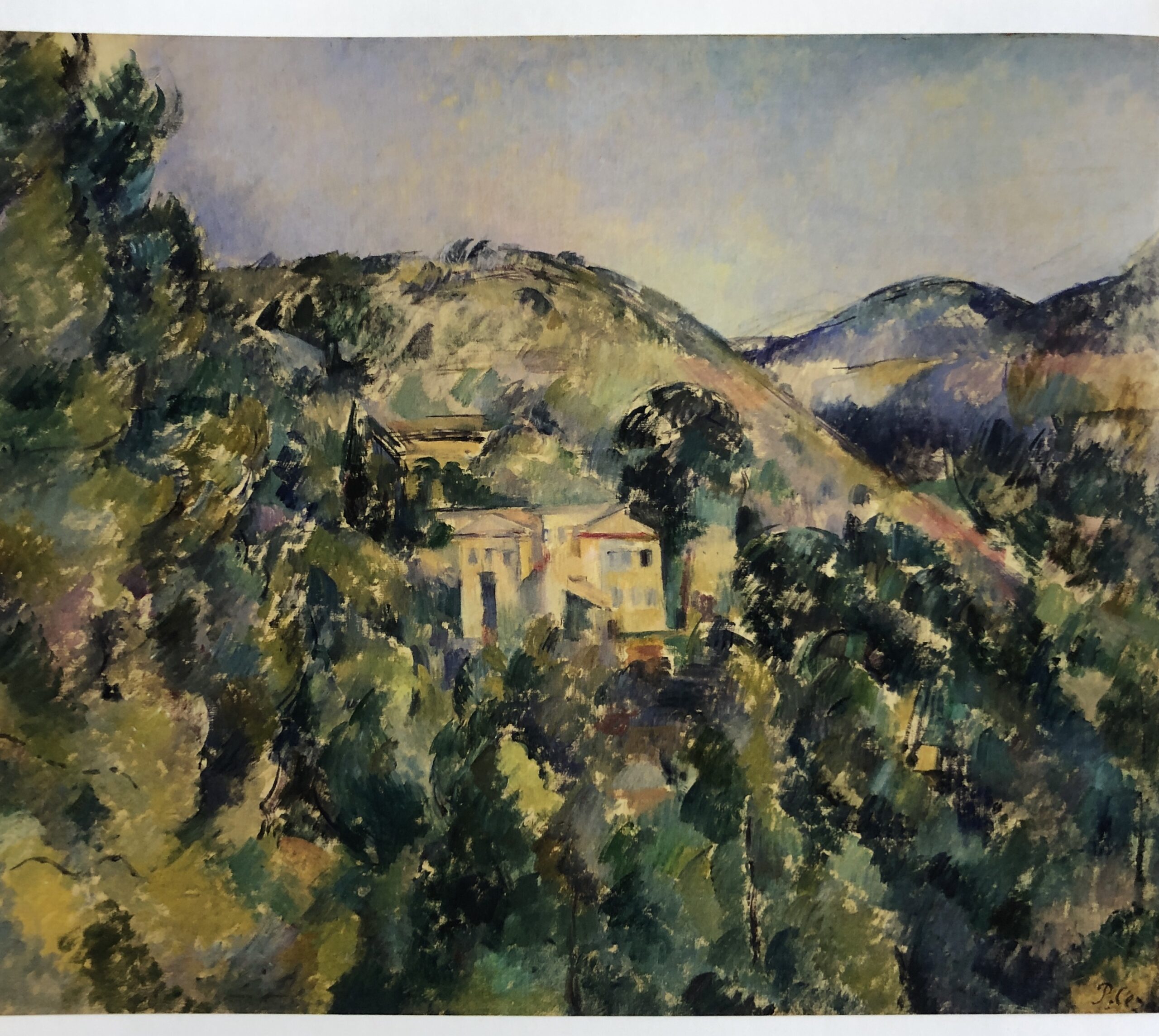

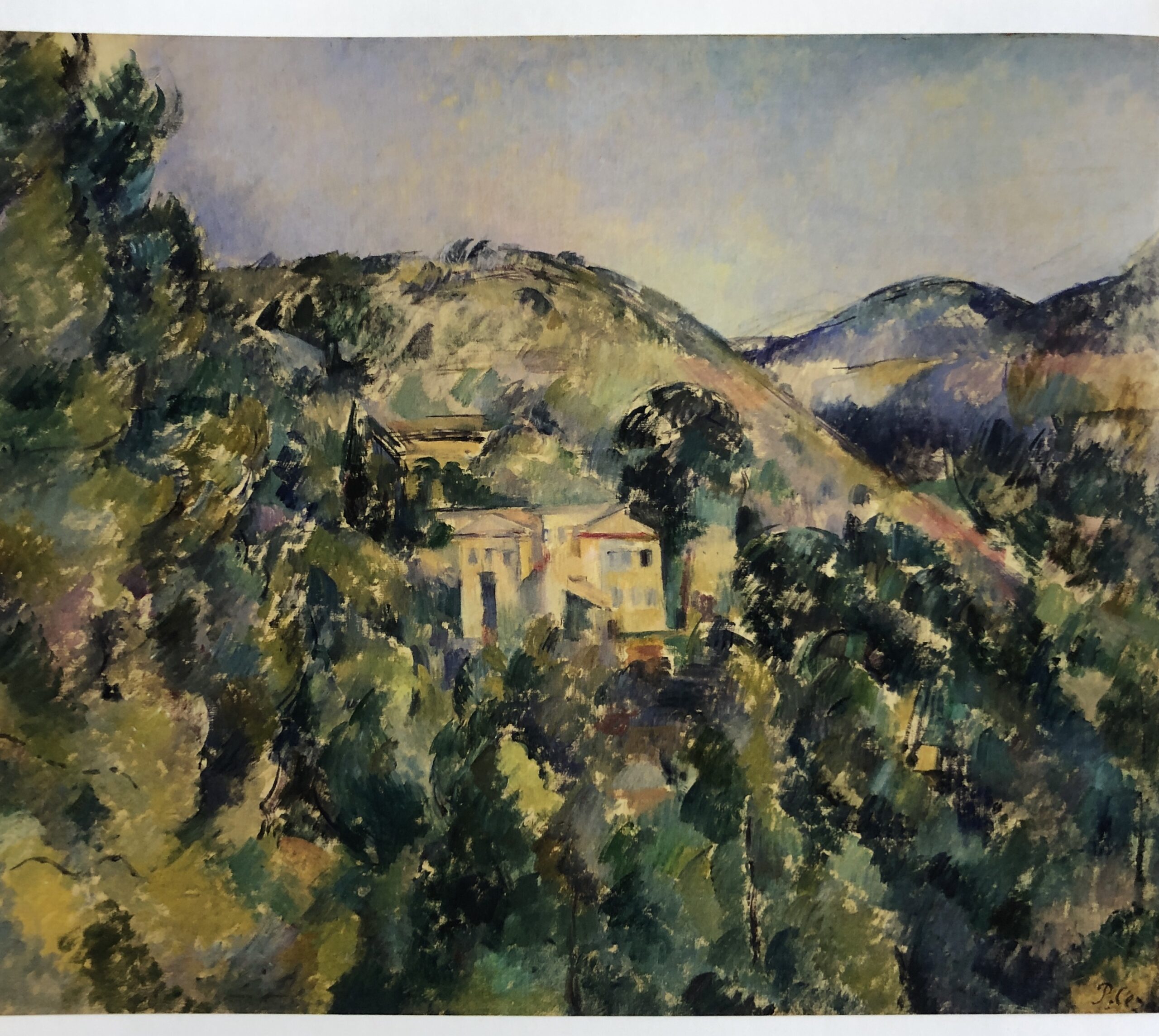

View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph, Metropolitan Museum of Art

I saw this painting almost exactly ten years ago at Cezanne and American Modernism at the Montclair Art Museum. After all these intervening years, I finally bought the catalog for the show. It’s a hardbound book once in the collection of the Art Institute of Pittsburgh Library, with the little envelope for the library loan card still glued just inside the cover. Purchased through a third party on Amazon, the book was finally a bargain. I bought it because seeing this show revealed so much about Cezanne’s influence on American painters and because this particular painting had such an impact on me when I was at the museum. I wanted to see the work in the show again after all this time.

The almost iridescent quality of the variations in color from the hillsides down into the forest, the way in which each mark hummed vibrantly in harmony with every other mark in that field of paint, left me more in awe of Cezanne’s color than ever before. I’m struck more and more by how Cezanne’s greatness has, for me, so little to do with his enormous historical influence. It’s ironic to react that way to a show designed to confirm his enormous affect on later American painters. But it seems that his influence had less do with with his theories–in other words his position in history–and seems so much more a result of the unique, lyrical feeling his paint inspires. His color, his handling of oil is almost always understated, and he seems to always find combinations of tone that make time itself visible–as Vermeer does in a different way. It derives from the intensity of his subdued passion for what he sees as he translates it into paint, which is hard to square, so to speak, with his famous dictum about interpreting nature geometrically, the advice that gave birth to Cubism. I wonder if his stress on seeing nature as sphere, cone and cylinder was merely an arbitrary way of imposing self-restraint to temper his passion for the colors of oil paint. He forced himself to think about form and volume rather than color and as a result his color became more subtle and unique. His actual achievement could have been almost as an incidental byproduct of the geometrical guidelines uppermost in his mind–even though color was what drove him to paint. Somehow, in the lower left hand corner, I see Gorky, of all people and I don’t mean the early paintings Gorky did which are hugely talented imitations of Cezanne. I mean his later paintings and his self portrait with his mother–the line and shapes and even a bit of the color. Cezanne is a marvel–and one can see why he could be classified as both an Impressionist and Post-Impressionist, though he was unlike everyone else in any category. He was perfectly himself.

January 13th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Les Indes Galantes, Johannes Muller Franken, at Louis K. Meisel Gallery

I saw this painting some years ago at an invitational group show at OK Harris, not long before the gallery closed, seemingly another little heartbreak in the cancer of real estate inflation in Manhattan driving out all sorts of businesses that operate on a human scale and replacing them with gentrified real estate and Google office space. I wonder how a simple corner bodega survives this slow, torturous cleansing by the tsunami of finance driving our metropolitan economies. That isn’t really why the gallery closed, but I’ve been wanting to rant about out-of-control inflation in big American cities. Many galleries have closed–or moved away like Arcadia, happily thriving in Pasadena now–because they can’t afford to stay open. In reality, its founder, Ivan Karp left instructions for how to wind down the operation when he died in 2012, and the managers of the gallery were simply following his dictates. He picked the name OK Harris because it sounded tough and American, like a riverboat gambler. Visiting on a whim five years ago, I saw one painting after another that startled me with its excellence, and this one left me gobsmacked at the raindrop-by-raindrop realism in mellow counterpoint with the scene’s romance and Maxfield Parrish color. Apparently, it’s still available at Meisel. How is that possible?

January 10th, 2020 by dave dorsey

The Cartographer, mixed media, 39” x 132′ x 104″, 2019

I loved the artist statement (I can’t remember if I have ever those words in the past) for this installation that won Manifest’s coveted $5,000 Manifest One award and single-work exhibition. Here is the email announcement with Indiana artist Damon Mohl’s statement below. I like the sense of exhaustion and lostness in his vision, which seems appropriate as a viewpoint on Western culture. But I loved , his statement about the genesis of his creative work–which apply to the most compelling creative work in general.

Manifest’s projects are carefully crafted exhibitions of engaging works from around the world, judged and chosen by a dynamic jury of working artists, creative professionals, scholars, and educators. Once each year, we honor an exemplary artwork and test the extremes of our selection process in ONE: The Manifest Prize.

The nonprofit Manifest Creative Research Gallery is proud to be celebrating a decade offering this momentous award supporting artists making exceptional art. Now in its 10th year, one artwork has been chosen from a pool of nearly 900 works by 192 artists from 41 states and 12 countries to stand out as the best in one of the largest artist responses this project has ever received. Seventeen jurors from across the U.S. participated in this multi-stage selection process.

It should be noted that the winner and finalists*, 11 works, represent the top scoring 1% of the jury pool. The winner represents the top one-tenth of 1% of the jury pool.

We are proud to award this year’s $5000 Manifest Prize and corresponding ONE exhibit to Damon Mohl for his work, “The Cartographer” which will continue on view in Manifest’s Central Gallery through January 10th.

Of his work the artist states:

“In 2018 I spent a month traveling the north and south islands of New Zealand. Leading up to the trip, I had completed numerous sketches for an experimental film. In truth, the many fragmented images never connected, and when I arrived I started filming without a clear sense of the project. Traveling in a camper van, I gradually woke up earlier each day and heard a cacophony of birds singing before dawn. One song, in particular, stood out because of its melodic, contemplative nature and haunting strangeness. I learned this was the song of the Bellbird, and for the rest of the trip, I set my alarm so I could make audio recordings of the Bellbird’s morning song. These recordings led me to a new idea, and I ended up creating an entirely different film.

I find it compelling the way an image or sound can lodge itself in the subconscious and open up an expansive idea. Creatively speaking, ideas that originate from a presumed understanding or with a specific goal are often prodded and forced into existence. Outcomes are narrow and predictable, even before they are developed. Everything is over before it even begins. The most exciting ideas arrive as mysteries. They create enigmas to be explored but never fully understood. Art is the language that embodies and evokes that which cannot be rationalized or explained with words and it is this revelatory journey that keeps me fascinated and dedicated to the process of creating. My work is firmly rooted in metaphorical narrative, but at the project’s origin, I relinquish as much control as possible. I often reach a place on sustained projects where I can no longer remember what propelled me forward in the first place. If the origin remains intact, it was strong enough to stand the test of time. If it fades, what came after was much more interesting to me.

The Cartographer was recently created for an exhibition of costumes, objects, and set pieces utilized in five different film projects over the past four years. Thematically, the film connected to this piece tells the story of a man whose mind is locked in an endless cycle, in which he repeatedly imagines himself on doomed 19th century expeditions. The voice-over narration provided on the nearby wall is also from the film.“

Artist Biography:

Damon Mohl (b.1974) is a filmmaker and interdisciplinary artist. His work bridges drawing, painting, collage, and sculpture with digital technology to create experimental as well as narrative-based films and works of art. He received his BFA in drawing and painting from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia and his MFA from the University of Colorado, Boulder. With a focus on filmmaking, his graduate thesis film was nominated for a Student Academy Award in the experimental category. He exhibits his work nationally, and internationally his films have screened in over thirty countries. He is currently serving as an assistant professor of art at Wabash College in Indiana.

January 7th, 2020 by dave dorsey

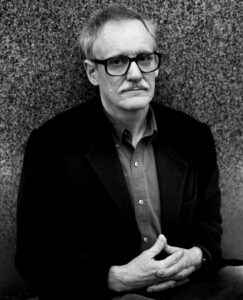

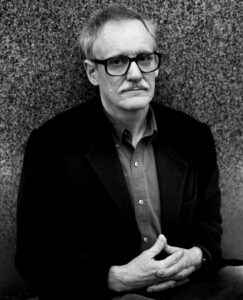

Peter Schjeldahl, courtesy The New Yorker

I was delighted when Jim Mott sent me some excerpts from Peter Schjeldahl’s sayonara at The New Yorker, inaugurating his retirement. I spend so little time reading magazines now; I missed it. May he move on to write a book, if he survives his battle with cancer long enough. The prospects don’t sound good. He’s always been my favorite art critic. I didn’t realize he had a faith, but it sounds as if it didn’t emerge until he quit drinking. Maybe I am reading too much into a couple sentences. In this cultural climate, it’s a brave move, albeit a bit quieter than Kanye’s, to offer a shout out to Christianity, which now seems to be equated unfairly with deplorable politics. It feels as if we are living in the cultural Dark Ages. (It helps if you quote Simone Weil; that “cherry on top” is a nice touch.) His judgments have almost always struck me as unimpeachable and delivered with wry self-awareness, meaning humility. The humility grows here to the proportions I consider de rigueur for an artist, and especially a critic. I agree with nearly any self-skepticism: I don’t know much, and maybe someday, if I’m good, I’ll know nothing, along with Socrates. Danto often has a similar tone of implied disclaimer: Well, this is how it looks to me, I could be wrong, but I don’t think so. But Schjeldahl’s doubt is less philosophical and more personal, hence more engaging and intimate. His first paragraph below says precisely what I recognized a few months ago after my father’s death, when I came across the Google street view photograph of the house my wife and I lived in during the first few years of our son and daughter’s childhood–the photograph did everything a work of art ought to do, and it was simply the tiny artifact of some camera mounted on top of a car moving past the house in the most impersonal way possible. It was essentially a surveillance shot. But it contained more than my world from those years; it gave me a window into the entire world, emotionally, imaginatively, and in some other way I don’t have language to pin down. I had been punished into receptivity at that point, granted, but there you go. That’s how it works. Danto would smile at the fact that the Google street view shot was art for me right then and there–though it would contradict his argument about the need for meaning–but it’s exactly what Schjeldahl is getting at.

From Schjeldahl’s farewell, courtesy Jim’s email:

To limber your sensibility, stalk the aesthetic everywhere: cracks in a sidewalk, people’s ways of walking. The aesthetic isn’t bounded by art, which merely concentrates it for efficient consumption. If you can’t put a mental frame around, and relish, the accidental aspect of a street or a person, or really of anything, you will respond to art only sluggishly.

I like to say that contemporary art consists of all art works, five thousand years or five minutes old, that physically exist in the present. We look at them with contemporary eyes, the only kinds of eyes that there ever are.

I retain, but suspend, my personal taste to deal with the panoply of the art I see. I have a trick for doing justice to an uncongenial work: “What would I like about this if I liked it?” I may come around; I may not. Failing that, I wonder, What must the people who like this be like? Anthropology.

Simone Weil said that the transcendent meaning of Christianity is complete with Jesus’ death, sans the cherry on top that is the Resurrection. I think so.

“I believe in God” is a false statement for me because it is voiced by my ego, which is compulsively skeptical. But the rest of me tends otherwise. Staying on an “as if” basis with “God,” for short, hugely improves my life. I regret my lack of the church and its gift of community. My ego is too fat to squeeze through the door.

Disbelieving is toilsome. It can be a pleasure for adolescent brains with energy to spare, but hanging on to it later saps and rigidifies. After a Lutheran upbringing, I became an atheist at the onset of puberty. That wore off gradually and then, with sobriety, speedily.

January 1st, 2020 by dave dorsey

Envy, from Giotto’s Arena Chapel frescoes

To paint pictures is to live in a state of paradox. What I intend usually just points me in the direction of what I achieve, and by not achieving quite what I want, I sometimes succeed in ways I wouldn’t have imagined and may not even realize. Occasionally I invest paint with something far better than what I could have intended or predicted. In every success, there’s a bit of surprise, if not discovery.

When you begin to realize how great paintings aren’t necessarily limited by whatever outcomes the painter desired, it dawns on you that this is how life itself works, almost invariably. All of your representations, all of your mental pictures of what matters in life fail to embody what it is you think those images represent. Try to picture anything—goodness for example—and whatever instance of goodness you imagine will fail to capture what it actually is. And, even if you lower your sights and accept the consolation prize of depicting what’s actually visible in life, even then, there’s shortfall. What you do picture to yourself as familiarly good will rarely resemble how living, new instances of goodness actually appear.

Early in Swann’s Way, Marcel Proust elaborates on a physical similarity between his cook’s pregnant kitchen-maid and one of Giotto’s figures of virtue and vice in his Paduan frescoes. It’s a little running joke between the novel’s protagonist and Swann, when he comes to visit and asks how things are going with Giotto’s Charity. As his focus shifts from the kitchen-maid to the painter, the way Proust elaborates on the Gothic painter, circling around his subject, reminds me of how Francis Bacon, in his essay on it, seems to turn the subject of Truth inside-out and then outside-in, until you are almost completely disoriented but left with a kind of Socratic doubt about your own callow assumption that you can actually know Truth. In the same way, you think you’ve understood Proust’s point and suddenly he seems to be saying just the opposite—this symbolizes X, but X is nowhere visible in the behavior depicted and yet the reality of X is embodied by it. Come again? It does make sense, but at first it feels like riding in circles on a Mobius strip. All the while he asks you to keep reconsidering what exactly is happening in Giotto’s paintings of virtue and vice—forcing you to go back and look at them. Which is both the first and last step in letting a painting do its work.

For years, I’ve considered Proust a purposely amoral novelist, someone so driven to see exactly what’s happening in human behavior and human consciousness, that he can’t stop to pass judgement on the behavior he depicts—not letting discriminations of good and evil constrain his phenomenology. Passing judgment on something gives you an excuse to ignore what you’re seeing. I’m beginning to think differently. In my third reading of this novel right now (first in college, second when the Kilmartin translation was published), I’ve delved only a hundred pages into the book, and it seems he was constantly thinking of goodness, interested in why his many of his characters found it so difficult to see and embody it. His ability to convey goodness was so fresh, so unsentimental, that it’s hard to realize what he’s doing as it happens on the page—in a way analogous to his consistent depiction of social and sexual relationships as detours that usually lead away from an authentic life. In a way similar to how I’m seeing this new dimension in Proust, this year I’ve become more and more interested in visual art that seems to be doing exactly the opposite of what I think painting and drawing should do when operating in its most innate way. Painting that has always struck me as the most fully realized has no meaning. Any effort to extract meaning from it is, in a way, to look away from what’s actually happening in the work, the awareness it can generate, and nullify it by translating it into thought. (In the same way, the best passages of Bergotte’s writing have an impact on Proust’s narrator unrelated to their significance. In one of his book’s quietly amusing moments, Bloch advises him to read only poetry that means nothing.) What’s most powerful in a work of visual art has nothing to do with meaning: deconstructing it will get you places, but it won’t replace the looking and often gets in the way. MORE

December 19th, 2019 by dave dorsey

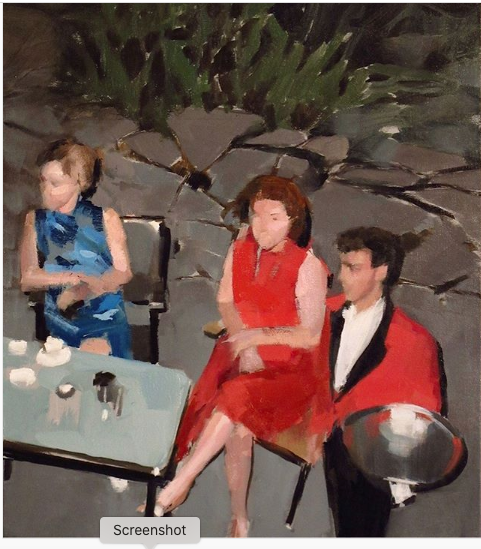

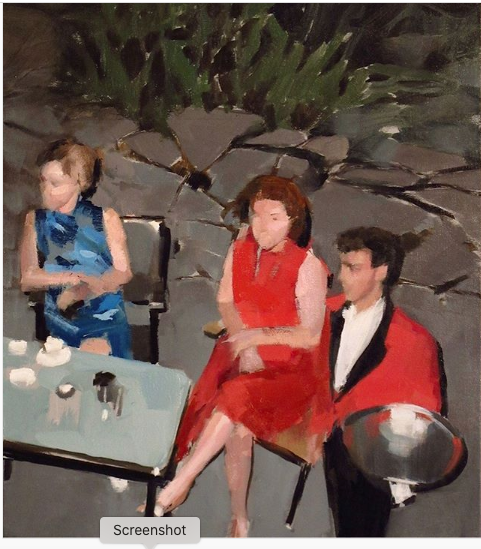

Mark Tennant, 20 x 16

Mark Tennant, 20 x 16. That’s all I know about this painting by an artist who has turned a bit of a corner in the past year or two–the simplicity of his execution has become extraordinary given how convincingly he puts one perfect tone alongside another. These chunks of color do exactly the job he asks them to do. In some cases he creates an almost expressionist surface that resolves, after a bit of viewing, into a bracingly convincing glimpse of women caught in a candid moment not intended for public consumption. No title, no medium nor indication of the support, though it’s almost certainly oil. He posts his work on Instagram and at his website, but it’s all untitled as far as I can tell. I did a post about an earlier painting of his not long ago, but couldn’t resist posting again, it’s so impressive. I found his scenes off-putting at first, murky and seemingly jaundiced visions of people lost in an eroticized world of youth and folly. Now I’m not bothered by lost-in-the-dark quality of his figures. The brushwork is so deft and accurate and minimal, as if he were the Fairfield Porter of cultural decline. At first, his work briefly brought to mind Eric Fischl and Richard Prince’s ironically prurient stuff, but this latest work feels more like early Richter. There’s a muted compassion in all of it, even though the scenes are illuminated unsparingly and the figures are mostly faceless. It all looks as if he has discovered troves of snapshots, Polaroids maybe and worked from them quickly–the way Martin Mull buys boxes of old, unwanted family shots at garage sales to use as sources. The bruised sexiness that runs throughout Tennant’s work is suppressed and seems almost accidental in many of the images–the young women are mostly unaware that there’s a guy with a camera eavesdropping on their misdemeanors, but in more than one of the paintings the women are hiding their faces. Many seem lit by flash photography, which adds to the tabloid feel that runs throughout, the awkwardness of bodies caught off balance or hunkered down in self-defense. He gets exactly how a single bright light source plays on objects in dim surroundings and his extremely abbreviated handling of paint captures the look and feel of an onlooker snapping a furtive high-contrast exposure of a compromised subject. The shot above could be from a cocktail party in the Hamptons or Connecticut, some partier with a Kodak Instamatic up on a balcony, gazing down at his bored fellow celebrants, the butler or caterer passing with his gleaming tray, with nothing to offer the idle women on the flagstone patio. The elegance and evening formality seem imported from America’s economic heyday, or else from last week in certain increasingly wealthy and isolated zip codes. Either way these privileged figures look as exposed and spiritually endangered as nearly everyone else Tennant captures unaware.

December 16th, 2019 by dave dorsey

Flowers in Starlight, enamel on canvas, 24×24, 2018

The artist’s individual struggle, individuation as Jung would have put it, as it worked itself out in her own career:

I wanted to paint what today looked like or felt like. But as I just grew older it didn’t seem as important to make paintings that were necessarily as contemporary as possible. I wanted to make paintings that I wanted to make. You don’t have a choice. You can try to make the work you think everybody likes, but that isn’t going to work. If I had never changed then possibly I would just be that person who made paintings that looked as if they were done in the 90s.

–Inka Essenhigh

I didn’t want to be light and girly and trivial and I suddenly was and I loved it and it was all okay. And I had an immediate sense of relief. I could tell stories and I knew that I was on the right track for making something that was important to me. I could pursue what you might call “the inner world.” I could sit down and look for certain images I wanted to paint and they would look a certain way, they would feel a certain way. They could have that feeling of child-like wonder and I could bring it forward.

–Inka Essenhigh

December 7th, 2019 by dave dorsey

I’m beginning to realize it’s entirely fair to classify some of my work as Pop, and I’m comfortable with the idea. It doesn’t clarify anything—categorizations and schools and movements just obscure what’s actually going on in a painting—but I’ve begun to warm up to what Pop was doing, historically. It made me uncomfortable in the past, because I didn’t arrive at what I do as a way of emulating Pop Art at all. I’m sympathetic with the non-intellectual aims of that movement, the notion that visual art can be accessible and enjoyable to anyone with eyes and that visual art can, maybe should be, entirely a perceptual matter. I’m happy that Arthur Danto considers Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes to have been a major philosophical meditation calling into question the nature of art and putting an end to the notion of progress in the history of painting—but I don’t think that sort of philosophical investigation was Warhol’s mission. Whether it was or wasn’t, Danto’s insight made me realize, in my thirties, that I could consider myself a contemporary visual artist, rather than just a latecomer. I don’t think Danto would agree with me that people now have permission to do exactly the sort of thing done in the past, without irony, and create work that is absolutely vital and compelling and fresh. But his insights make this conclusion inescapable.

I conclude from Danto’s thesis that for the past seventy years or so artists have been free to do anything at all, including exactly the sort of work that has been done in the past, and what they produce can be considered entirely relevant and contemporary. Everything is permissible because anything can be art. (This doesn’t mean anything is great or even good art: that’s as rare as it ever was.) Ending the tyranny of art history is the last, great liberation for individual painters—and it was Danto’s genius to recognize all of this. The challenge now is to become oneself, in whatever idiosyncratic way works, even if the outcome looks like a painting rooted in traditions from thousands of years ago. Picasso already understood this between the wars when he was borrowing stylistic inspiration from Ingres and the figures on attic vases for the Vollard Suite. Continue reading ‘Fine, Call Me Pop’

November 21st, 2019 by dave dorsey

The Light in The Room, detail, oil on linen.

My most recently finished still life makes me uneasy. If I look at it in a dim light, before going to bed, I’m gratified that I did almost exactly what I set out to do—capture a glowingly illuminated kitchen in the middle of a bright, summer day. But during the daylight hours, if the surface of this painting is well-lit, I want to crawl into a corner and close my eyes.

I had this same feeling a year ago last month when I went to see my prominently displayed paintings—I could see them through the front windows of the museum while parking my car on the street—at the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art exhibition in Wisconsin, jurored by Frank Bernarducci. Once I got up close, by virtue of the unsparing gallery lighting, the brushwork made my skin crawl. I felt exposed. The execution didn’t appear to have bothered anyone else, considering the placement of the two paintings. But ever since that opening, I’ve been concentrating on the thickness of the paint—endeavoring to get a Goldilocks feel, not too thick, not too thin—and the way I need to handle it, wet on wet. I’ve been conscious of the desire to user thicker paint for years, but this determination to paint wet into wet began when I returned from Wisconsin last year. (I make exceptions when this isn’t possible, when I see something in the already dried coat that makes my stomach tighten with disappointment, as it did yesterday with the taffy painting I’m doing now. But I make my amendments by putting down uniform areas of wet color and then going back to push detail into them immediately.)

I don’t want what I’m rendering to look hyper-realistic. The paint should look like paint, not the surface of a photograph. But it needs to flow gradually from one spot to the next. No rough edges where edges don’t form clear lines and borders in the source. So now, today, the formerly irksome part of the painting doesn’t make me want to hide when I look at it. It’s all about the nature of the brushwork, the energy and visibility of the mark (or just the way the paint flows from one tone into another) as catalyst for how the eye flows across the image and reads it. I don’t expect my brushwork to be what it is in Van Gogh, or Sargent, or Manet, or Hals, or Thiebaud, or Jenny Saville. But the brushwork now doesn’t get in the way of what pleasure I get from looking at what I’ve done. It isn’t at odds with the image. But when I see areas where the paint is applied skillfully in terms of value and hue, but it just looks awkwardly scumbled, dragged across already-dry paint, and the edges of each spot of color make it look scuffed and chaotic, then I want to slip the painting away into storage. I don’t, because it’s a decent enough painting. Yet his knowledge doesn’t help, which I take as a good thing. Excellence requires striving.

It’s all about whether or not the eye bumps into a spot of paint or glides over it, riding the energy of the paint itself, the life it imparts to the act of looking. I am probably right in reacting this way to the work I’ve done. But maybe not. When it comes to painting, it’s best not to be certain of anything except in those rare cases when I know the painting is really finished and as good as I can make it. (I’m certain about the prefection of most of Vermeer, and quite a bit of Piero, but that’s a pretty safe certainty and though I know I’m looking at a painting when they’re the ones making it, the marks they make aren’t all that visible.) The less refined execution might end up being what people value most in some of these paintings I want to avoid seeing—the way in which the surface is at odds with the image it induces you to see. In fact, I’m constantly trying to do smaller, more improvisational paintings that are all about the visibility of the paint and where the areas of paint look abstract and unrecognizable up close—in other words, simplified and much more painterly work. But this isn’t what I’m after in the sort of paintings I’ve been exhibiting over the past decade—with the exception of one small interior with figures, quickly executed with easy brushwork, I showed at a pop-up in London years ago.

The humorous element here is that with either kind of brushwork, my current painting looks roughly the same from a few feet away—and the magic of Chardin resides in how, up close, it is just a chaotic mess, while a little farther away, it’s amazing. But it’s a good chaotic mess up close. His paint was thicker, more sensuously applied, more like Thiebaud than Vermeer, so that the paint itself was a pleasure to see. As opposed to what I’m dealing with. But I’m working on it.

November 18th, 2019 by dave dorsey

The Window, Matisse, oil on canvas, 57″ x 46″

One of the treasures from my visit to the Detroit Institute for Arts Museum, and displayed near two equally excellent paintings. Historically speaking, it’s only a short walk from this painting (hanging with two equally beautiful pieces by Matisse) to the work of Richard Diebenkorn. Yet this was painted half a century before Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series. What’s baffling is how so much lyrical feeling can be invested in such a restrained and limited range of colors.

last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order

last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order