Archive Page 38

October 8th, 2013 by dave dorsey

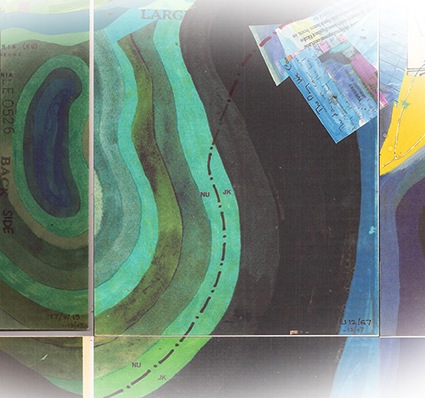

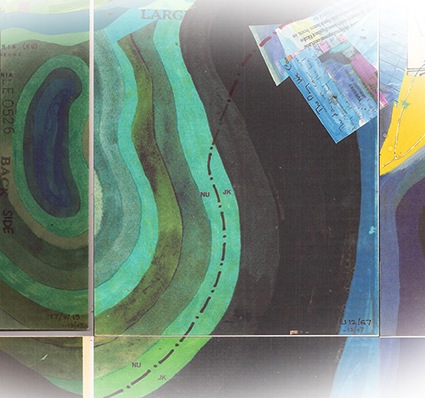

How many works of visual imagination have ever required fifty years of labor? That’s how long Jerry Gretzinger has been working on his ever-changing SimCity-like map. Hey, you have to get it right if you want the citizens of virtual Ukrania to find their way around. Google maps won’t help, yo.

How many works of visual imagination have ever required fifty years of labor? That’s how long Jerry Gretzinger has been working on his ever-changing SimCity-like map. Hey, you have to get it right if you want the citizens of virtual Ukrania to find their way around. Google maps won’t help, yo.

October 7th, 2013 by dave dorsey

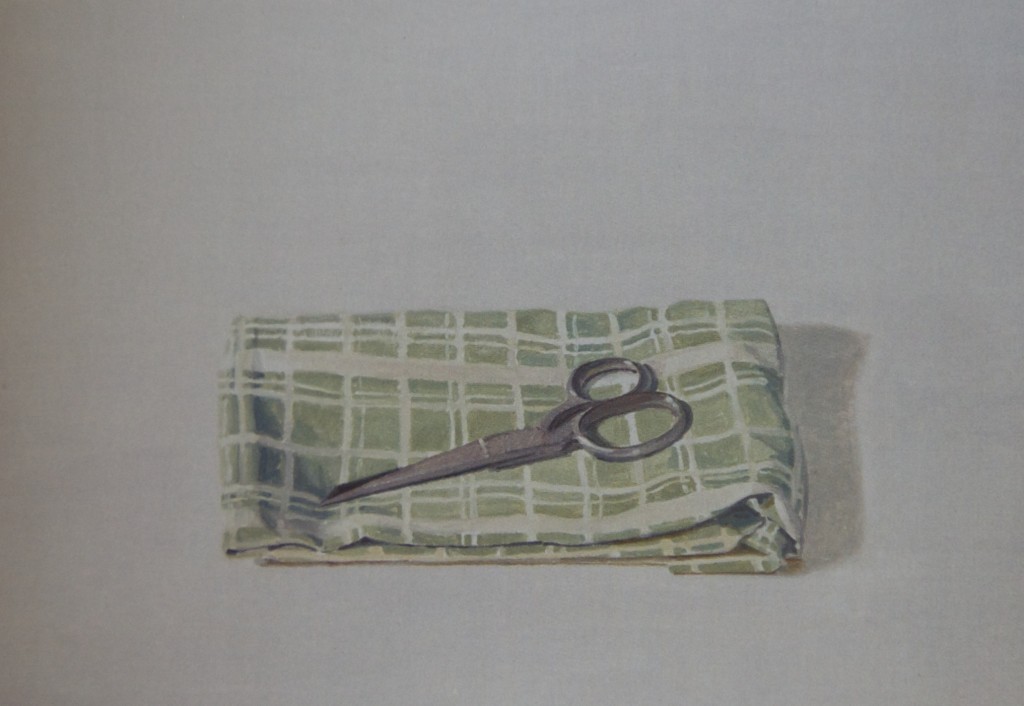

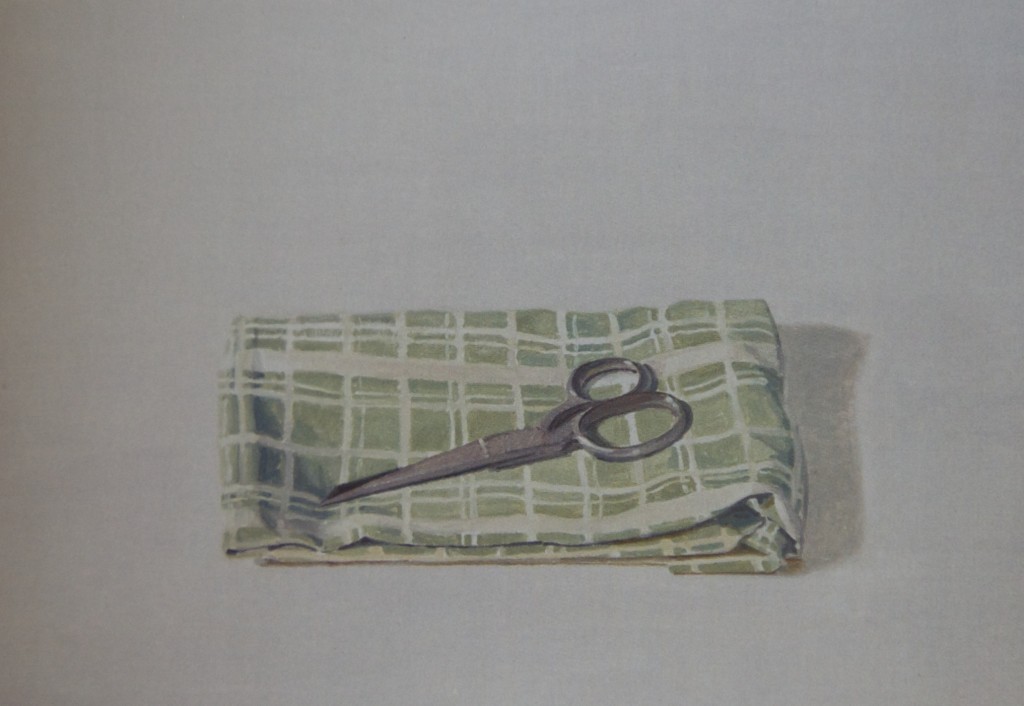

Scissors, Ron Milewicz, oil on linen

Spools, Ron Milewicz, oil on linen

I’ve never posted two paintings from a show I’ve written about, so that alone ought to indicate how much I liked this one. One of the deepest pleasures of my visit to Chelsea two weeks ago was seeing the quietly commanding still life paintings of Ron Milewicz at Elizabeth Harris. Having been given a free copy of the exhibition catalog, and reading the background on the show, entitled the soul exceeds its circumstances, I was conflicted, in a good way, about why the show worked so well. To say it “worked” is to diminish the subtle effect it has on you, at a purely instinctive and visual level. Even without knowing what inspired the show, you can feel these paintings are the outcome of restrained passion and love simply in the way he paints. You see image after image of modest household items, painted in an almost casual and un-assertive way, each object isolated in a field of white or Rembrandt-murk. The artist carefully depicts what he sees without fussing over hyper-realistic detail. These images immediately win you over with their humility, offered through an easy and relaxed execution. In painting after painting, you sense that Milewicz was working entirely within himself, as they say in sports, not striving to do anything more with the paint than he needed. Not trying to impress or dazzle with his skill; simply getting each object to the point where it’s all his own eye required to feel the life of the object. A brick, a shovel, a braid of challah bread, spools of thread, a hydrangea blossom, or a pair of scissors resting on a neatly folded cloth: they look as if they could smile back at you. Walking through the show, you feel as if you’re seeing tiny glimpses of the good life, in the highest sense, governed by an orderly middle-class serenity earned through hard work.

You might pause and wonder, as I did, why challah? Oh right, the artist is Jewish. Then, out of curiosity, you ask for a catalog and read the guest essay and the artist’s brief statement about his inspiration for the show. You realize this isn’t simply a refined way to make the simplest possible set of still lifes, but—looked at as a whole—this show is a fragmented narrative. These are glimpses of the happy life the artist’s grandfather led when he came to live in Brooklyn and work as a sample maker in Manhattan’s garment district. He and his wife apparently were gardeners as well. Yet you discover the deeper history behind each object when you read that Eli Milewicz weighed 60 pounds on the day Germany lost WWII and his “death march” to the Baltic Sea ended. His wife, Anna Kaplan, was also a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps. So you go back and look at each image and see the resonance of the horrific past in each painting: suddenly bricks mean a different sort of oven. A shovel is for digging both gardens and graves. Spools of thread struggle to breathe in their sealed plastic bags. And so on. If you are going to make a statement about anything, let alone something as evil as genocide, then it’s hard to imagine a more understated way to sum up an entire individual life in a set of images that have double, or triple, meanings. The show as a whole is a book of innocence and a book of experience, with both states of the soul fused together into half the images Blake required. And every one of these paintings is beautiful.

If art depends on commentary and knowledge extraneous to the image itself—and I generally hate it when that happens—then this is how it should be done. The paintings work well, entirely on their own, without background information, and yet they gain in gravity and, frankly, are even more interesting, when you hear why Milewicz was moved to paint such fraught images in such a sotto voce way. As Tom Sleigh puts it in the catalog essay: “The power of Milewicz’s images inheres in how he refuses to go in for the big teary-eyed gestures, and how ordinary objects like shovels, overcoats, and spools of thread are invested with deeper meanings. . . .but without insisting on them.” Those last five words are the key. The ‘deeper’ meaning is there if you wish to uncover it. Instruction isn’t included in the work itself, nor is it required. These are first and foremost paintings, not propositions. And very good ones at that.

October 6th, 2013 by dave dorsey

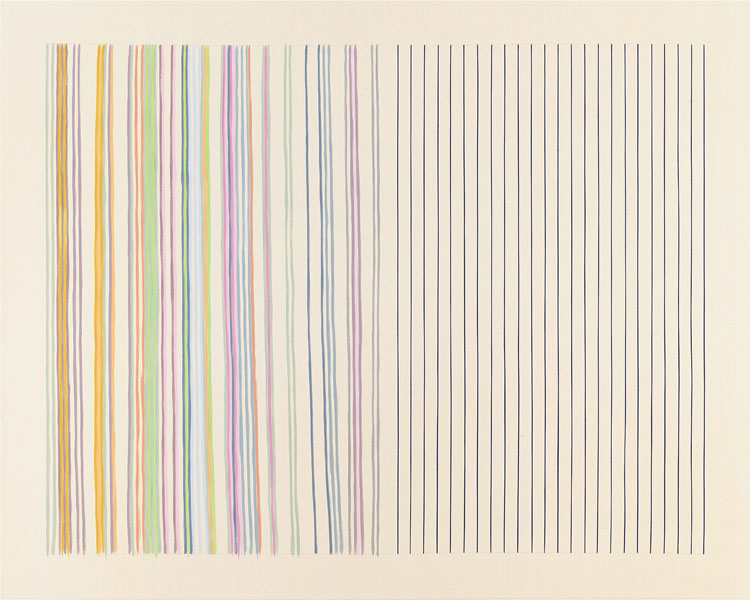

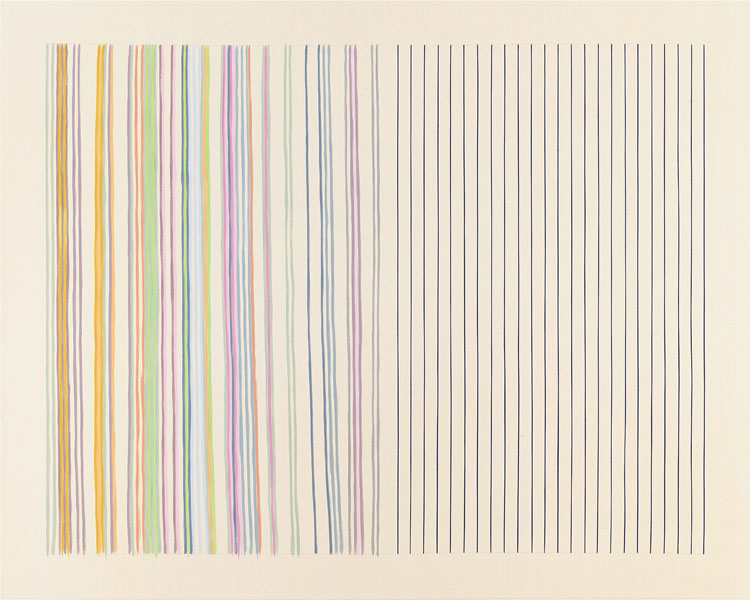

Mirror, Gene Davis, acrylic on canvas

After you’ve seen the more stident work of Ian Davenport at Kasmin–he drips orderly vertical stripes down aluminum and steel panels and then gets the paint to go all Dionysian on us near the bottom–walk a few blocks down to Ameringer McEnergy Yoho for something that looks at first quite similar but feels entirely different. Get up close to one of the Gene Davis canvases, and if you look intently enough you’ll see a perfectly straight pencil line just visible through some of the stripes. He used a straight-edge to establish where he wanted the stripes to go, but then painted them without any assistance other than his eye. The line was more of a suggestion than a rule, though most of the paintings don’t show how unsteadily his brush moved down the canvas until you really stand a few inches away. Math and human muscle are at odds in so many ways, but here it’s a good thing: minimalism seems friendly and humble and understated. I walked past these paintings on my way into the back room without paying much attention, but on the way out I stopped and tried to examine how he applied his paint, and it changed my attitude. A line of graphite, and then freehand. No masking tape for this guy. Suddenly, I started liking what I saw. It also helped, for some reason, to read this in the handout, though I really don’t quite understand it:

Look at a painting in terms of individual colors. In other words, instead of simply glancing at the work, select a specific color such as yellow or a lime green, and take the time to see how it operates across the painting. Approached this way, something happens, I can’t explain it. One must enter the painting through a single color.

–Gene Davis

October 5th, 2013 by dave dorsey

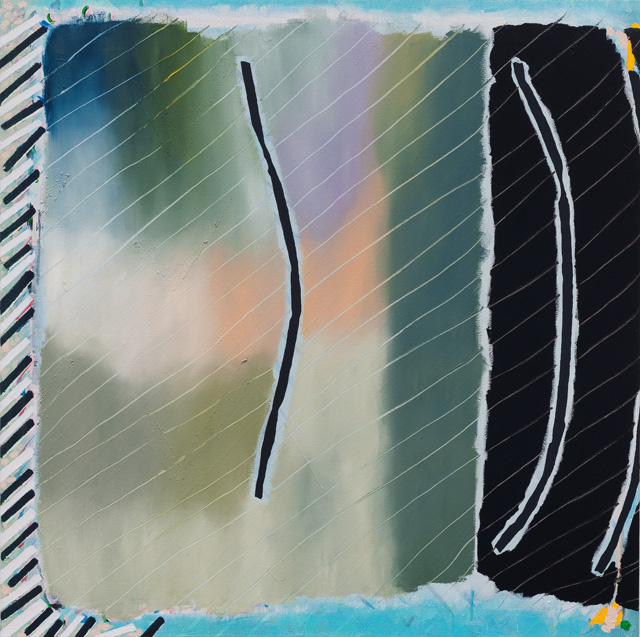

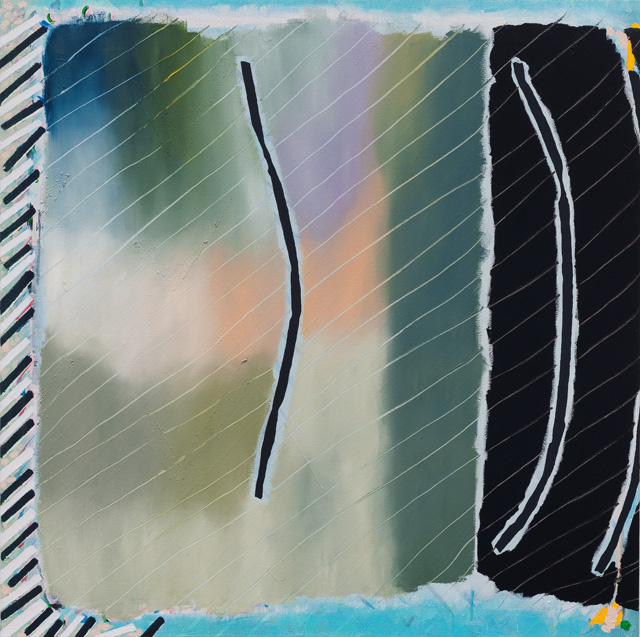

Allison Miller, “Wave” (2013), oil and acrylic/canvas, 36 x 36

I see a narrow depth of field, and therefore a background completely out of focus, glimpsed through rain, as my windshield wipers hit their apex, and I miss mine while steering through the turn. But I could be dreaming all that up. Definitely going to see this show when I’m back in the city this weekend.

From Hyperallergic:

The recent show further convinced me that Miller — who refuses to make work that is stylish, seductive, charming, nostalgic, retro, ironic or hip — is up to something. It is not that we wouldn’t recognize a Miller painting as such, it’s that she refuses to give her work a look. And in order to do this, and to keep everything in play while working on a painting, she seems to understand the necessity of exploring a territory that hasn’t been colonized by discourse, that hasn’t been snatched up and packaged by critics and theorists as the latest example of postmodern capital. I am further impressed by the fact that she refuses to affix a spiel to her work. I become distrustful when the artist resorts to a verbal component to deliver the enlightenment. –John Yau

So refreshing to read all of those sentences. I may post that somewhere as a manifesto, even though I fear I may give the appearance of violating much of it myself in the coming months. Doh. I actually have an idea for my solo show in May–until now I had hoped, as a painter, I possessed a mind so fine no idea could violate it. Apparently not. I pray I will recover from this after a spot of rest, once I’ve gotten it out of my system.

October 4th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Tryin’ real hard to be the shepherd in Chelsea

As I headed down 10th Ave. a couple weeks ago, I saw, for the first time, the at-first-glance bucolic installation of sculptured sheep by Fancois-Xavier Lalanne, where once I would have seen lines of cabs stretched into the avenue, waiting for gas. Paul Kasmin and real estate developer Michael Shvo have turned what was a Lukoil gas station into Getty Station, an outdoor gallery, complete with white fence, fake rolling pasture, and a soothing herd of sheep. It isn’t the first time the station has been used to exhibit art, but in the past, the gas kept flowing. The name is a nice turn: suggesting both the petroleum and the art associated with the Getty brand. Also nice: gas prices on the vertical sign have been replaced with the show’s opening and closing dates. A dignified gallery minion guarded the art and handed out leaflets about the show. The gas station’s metamorphosis has gotten a lot of publicity—it’s friendly, funny, a natural target for cell phone photographers. It’s nicer to walk past this site now than it was a month ago when overheated cabs clogged the sidewalk and street. They exhaled a bomb of exhaust that cloaked the entire corner. But they were there because we needed them, and they needed that gas station. It was a handy stop for people in the neighborhood who wanted a lift and income-sustaining for the drivers. (Kasmin told the Wall Street Journal that many have asked him, “Where can I catch a cab now?” Gosh, I don’t know. By walking a couple blocks and looking for the glowing number on the roof, maybe . . . )

My reaction to the change was mixed. Two weeks ago, as I walked through once-familiar areas of West Chelsea, I saw one example after another of a real estate boom. Across from the building that houses Viridian Artists and many other galleries, and which serves as home base for me, a large complex of “affordable housing” has been going up for months. Now, on the corner of 10th and 28th, where we used to buy sandwiches, Diet Cokes and an occasional beer, our friendly bodega was gone, and the site was locked down with steel shutters. I was told residences are going to be built there as well, and developers have pushed the little shop a block north to 29th. All of this would be encouraging, if I hadn’t lived through 2008 and witnessed the fallout of the real estate debacle ever since. When I stood at the edge of the pretend picket fence at Getty Station, all I could think about was the Wal-Mart syndrome—big money coming into an area and snuffing little enterprises on Main Street. Only in this case it’s big art money shutting down what appeared to be a small, thriving franchise serving a vital need for cab drivers hustling to make a living. The sheep are pleasant, but no one needs them. That gas station was alive, and small businesses exhibiting that station’s healthy vital signs are all that will turn the current economy around. Walking through so many galleries in Chelsea, as I do whenever I come to town, it already feels like walking through a string of high-end car dealerships, where the price tags are so out of reach for nearly anyone but the ultra-rich, you feel as if you’re peering through someone’s window into a lavish dinner party. Every time I walked past the old gas station, it was nice to see a little hint of how most people scrape together enough to pay the bills and keep a car running. It was a quick little sniff of reality on my way between the clean, filtered air of one white cube and the next. Those industrious cab drivers getting their tanks filled at the old Lukoil station were the sort of mudders who keep the American horse race alive. This installation of artificial sheep was cute, family-friendly, amusing and cheerful, but it depressed the hell out of me. I looked at the gallery attendant and shook my head, with a half-smile, and said, “Chelsea.” He nodded and smiled right back in exactly the same way, and said “Yup”, and then handed someone else one of his leaflets. I could have just said, “America.”

October 3rd, 2013 by dave dorsey

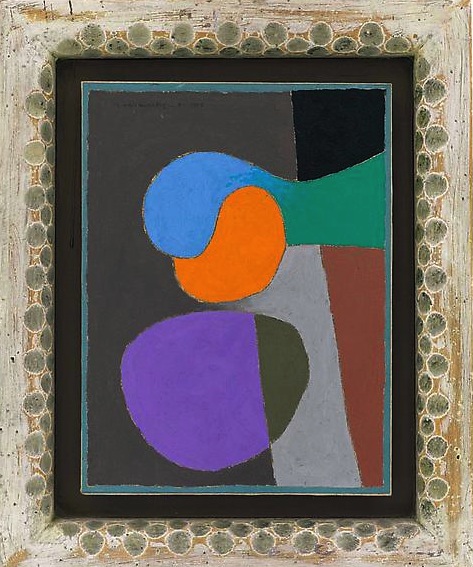

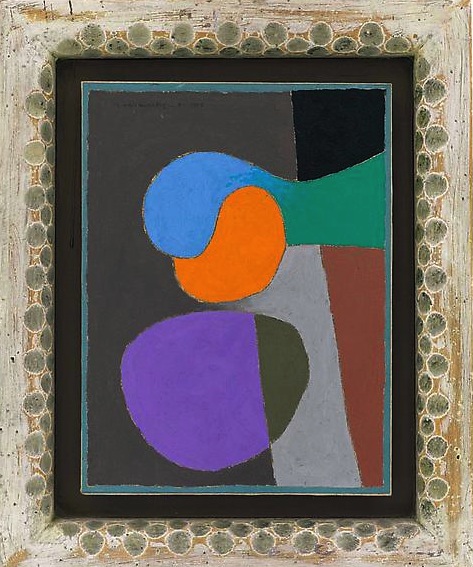

Frederick Hammersley, Got Is Love, 17.5″ x 14.5″

Until a couple weeks ago, I’d never been in the back room at Ameringer McEnery and Yohe. For another week or so, that semi-hidden room in back is full of Frederick Hammersley. (I had no idea the gallery had this third exhibit space, more or less concealed behind the desk. Evidence of slippage in my powers of observation. Doh.) It’s another taste of perfection, two years after their last Hammersley show (was it that long ago? you see my point about slippage . . . ), and though it isn’t quite as dazzling as the previous selection, it’s a pleasure. All the qualities that won me over before are in evidence again: the color harmonies, the tension between the organic abstracts and the geometric ones, the playful puns in the title. Got Is Love, for example, above. As a noun, it’s German for God, but it’s a verb for something else entirely, serving as a nice little commentary on American consumerism and plain old avarice. You love what you own. Is that a sales pitch, disguised as a title? Artists have to eat, contrary to common lore. Hey, cigarettes and Pernod are expensive too, for that matter. So if he’s saying love me, buy me: maybe that title isn’t so acerbic, after all. As with Hodgkins, the frame is integral to the painting and gives it even more presence as a three-dimensional object you look at rather than see through. In these paintings, as well as the minimal stripes from Gene Davis that dominate the gallery as the main event, you see the evidence of the unreliable human hand everywhere, unable to hew perfectly to any line, curved or straight, if only you get close enough to see how things meander a bit. In both cases, the wavering edges open up a world of feeling where you might first just see a cool and calculated exercise. The edge always striving to get back to where it belongs, as we all do in life, for better or worse.

October 2nd, 2013 by dave dorsey

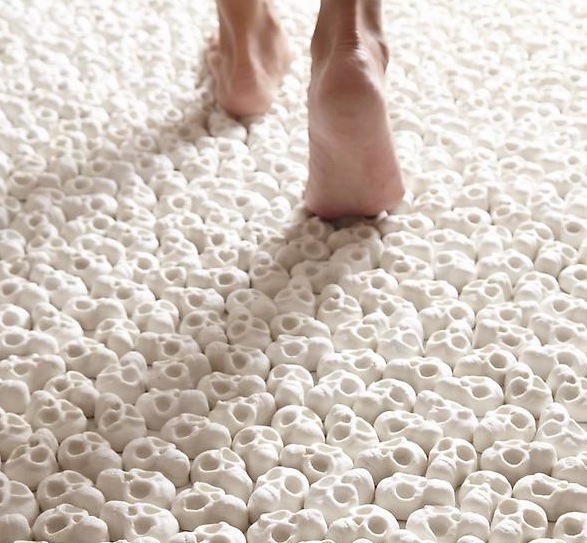

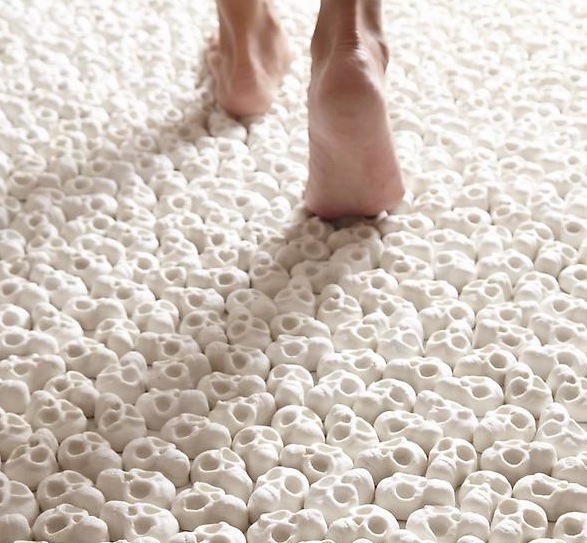

Skull installation in Singapore

I was hiking a few days ago through Mendon Ponds Park with my brother, and the subject of my skull paintings came up. Like many people, I think he assumed I’d developed a slight, morbid side-interest in death. I tried to explain that skulls go back centuries as a primary subject in vanitas still lifes. A skull painting isn’t a nice Goth fashion statement, or declaration of allegiance to the occult, or a logo for an Ivy League secret society, or an initiation into the Sons of Anarchy Painting Guild. Skull paintings were, and are, a reminder of what matters most in life: you may die at any time, so live accordingly. Every moment counts. Awareness of life’s brevity helps reveal how meaningless most pleasures are. Of course, as time runs out, you might also go on one sort of binge or another, but that’s simply testimony to how a vanitas paintings test of the viewer’s character. What are you going to do with whatever time remains? Vanitas painters themselves don’t always pass the test. They like to sneak into their paintings delightful but suitably evanescent sources of “meaningless” pleasure, thus giving themselves and their patrons an excuse to revel in those pleasures while feeling righteous about how brief they are. Barkeep, I’ve just contemplated death for fifteen seconds, make it a double. I’ve earned it. The vanitas tradition is certainly alive in Singapore where Nino Sarabutra has covered a gallery’s floor with 10,000 tiny skulls. I’m not sure if visitors are required to go barefoot, as it would appear in the photograph, but they ought to be. On one wall hangs a painting with the words: What Will You Leave Behind? Nothing morbid about this at all: it’s a question at the heart of any serious philosophical or spiritual attitude toward life. Nota bene: skulls can actually be beautiful in their own way, like old bleached objects washed up on a beach, as complex and full of curving, pitted forms as difficult to paint as a fading white flower. Our bones are like driftwood.

Now that’s the spirit . . .

October 1st, 2013 by dave dorsey

There is no love of truth without an unconditional acceptance of death. Everything which is threatened by time secretes falsehood in order not to die–and in direct proportion to the danger of death.

—Gravity and Grace, Simone Weil

September 30th, 2013 by dave dorsey

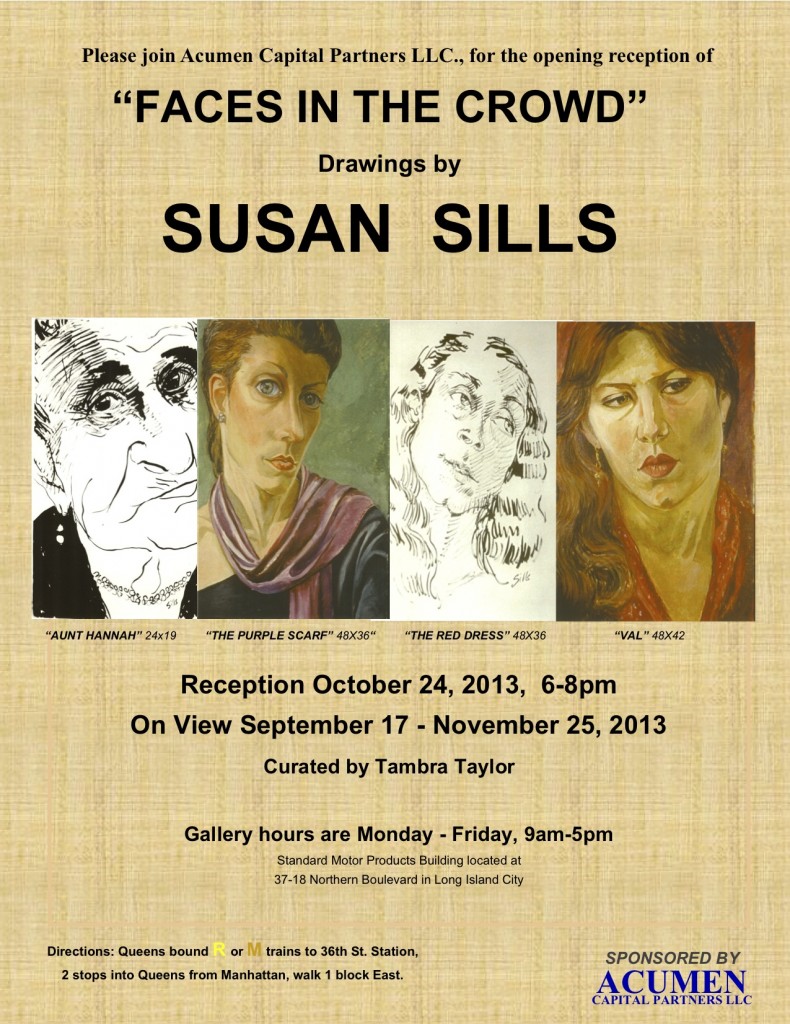

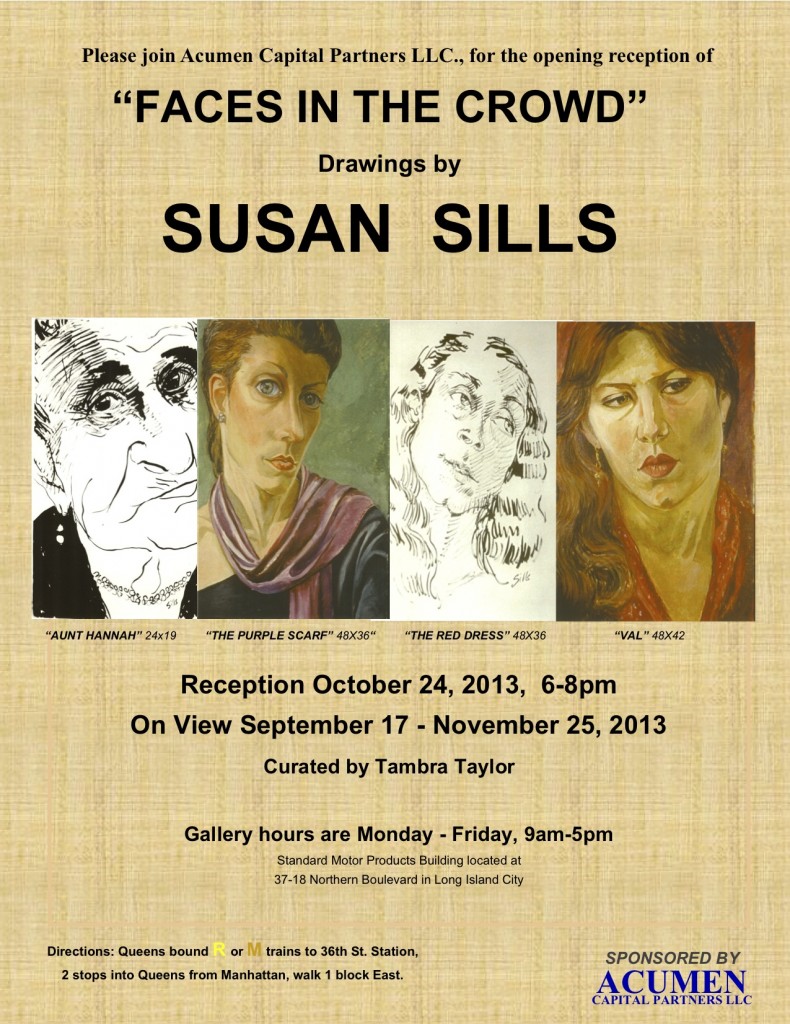

Faces in the Crowd, a show of drawings by my fellow Viridian artist, Susan Sills, opened recently in the lobby gallery at the Standard Motor Products Building in Long Island City. It’s a range of work she’s done over several decades, mostly ink drawings, but including one large painting as well. It’s a departure from the work she shows at Viridian, her three-dimensional wooden cut-out pastiches of works from art history. This is a show that reflects how she reacts to what she sees every day, and what she notices most are faces. In earlier years, while riding the subway, she would always have a small sketchbook and capture faces sitting across from her.

“A pen was a part of my hand back then,” she told me. “Today I just look.”

She prefers working from life, though she has included portraits of family members from the past hundred years, using scrapbook photos. “I do the eyes first. I know that isn’t the way you’re supposed to do a portrait, but I have to do it that way. When you start, your sitter is really looking at you intensely. Then they start to drift. You have to get the eyes when they’re paying attention.”

If forced to choose between painting and drawing, she would prefer to draw. In his campaign against photography-based painting, David Hockney said much the same thing: that painting should essentially be more like drawing, an immediate transfer of energy from the eye, through the heart, to the hand. At the time, he switched to watercolors, which are often considered drawings, rather than paintings. Hockney built his campaign, in part, on his celebration of a single brilliant drawing by Rembrandt, A Child Being Taught to Walk, where with only a few spontaneous and irrevocable strokes of a reed pen he evoked an entire family scene helping a toddler take her first steps. It’s closer to calligraphy or Japanese sumi e than most Western art. When I mentioned how drawing often feels more alive than painting, and mentioned how Van Gogh and Brueghel’s drawings seem to breathe more than their finished paintings, she immediately said, Rembrandt. “He was a genius as a painter, but his drawings are genius-plus.”

The show runs through Nov. 25.

September 29th, 2013 by dave dorsey

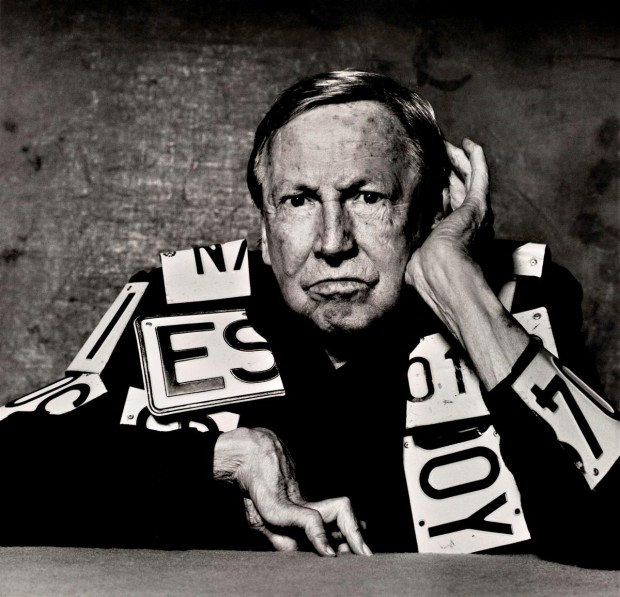

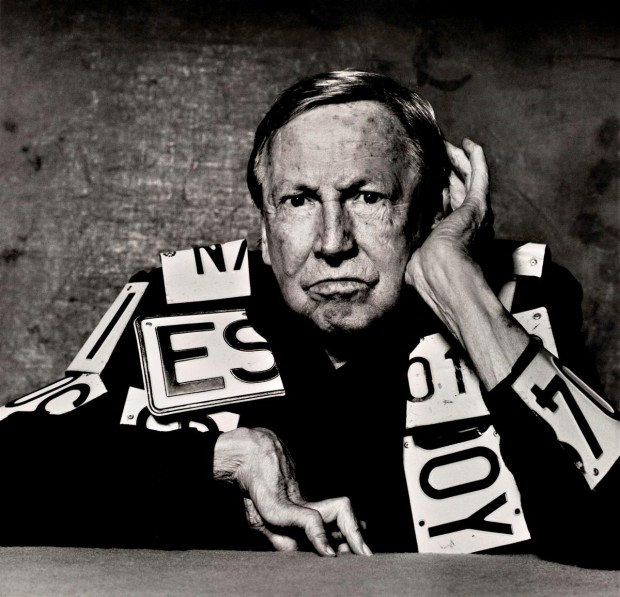

“While at bootcamp in Farragut, Idaho, Rauschenberg got hold of a set of oil paints and began a portrait of one of his fellow recruits. Working on the piece proved a bit of a challenge “…because the john was the only place with lights on after taps,” he says, “I sat in there to finish it. When I ran out of red, I pricked my finger and rubbed it into the skin tone.” After bootcamp, Rauschenberg was assigned to the hospital corps at Camp Pendleton, near San Diego. Before he reported for duty, he visited the Huntington Gardens, where three paintings changed his life: Pinkie by Thomas Lawrence, The Blue Boy by Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds’sSarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse. Up until this point, Rauschenberg had never seen original oil paintings and had no idea there was such a thing as being an artist. What struck him, he told Time magazine’s Robert Hughes was “…behind each of them was a man whose profession it was to make them. That just never occurred to me before.”

“. . . Rauschenberg thought of (Albers) as his most important teacher. “He was a beautiful teacher and an impossible person,” he said in an interview, nearly 20 years after Black Mountain. “I’m still learning what he taught me. What he taught had to do with the whole visual world, and it applies to whatever you’re doing, gardening or painting or whatever.”

September 28th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Red Rain, detail, Darryl Moody

The title of this show of objets trouvés could be the standard subtitle for any exhibit in a gallery setting, but it’s especially pertinent here, where the artist has captured photographic images from walls in cities around the world. Generally these walls are covered with an interesting and disintegrating surface of paper, paint, rust, dirt, and other layers of artificial skin, so to speak. While doing a critical assessment of work by artists in a residency at Cooper Union, Peter Schjeldahl once told Darryl Moody that his photographic prints reminded the critic of Aaron Siskin‘s work. This was after a long sequence of brutal dismissals aimed at other participating artists. Darryl asked The New Yorker critic if he could repeat that remark, and he got a nod. Few and far between are the artists who can carry around a blessing of any sort from Peter Schjeldahl. I had a brief chance to get a look at the photography on my hectic visit to the city on Thursday, and seeing it in person is the only way to absorb the subtle color of the prints. Not to dismiss the other strengths of his work, but his handling of color gives many of these images an especially poignant quality, a sense that weather and time are investing a rough beauty into something torn and punished that pushes back against what are otherwise lonely glimpses of loss and entropy. I’ve been looking at a smaller reproduction of the peeling image of Castro for the past two years at the gallery, but in the larger exhibited print, the steak of color he captured that runs through a rupture in Castro’s face is remarkably complex and almost melodic. Moody wanders around the world looking for images on walls to shoot, and half the success is simply finding a haunting image by spotting and cropping a particular area of what he sees. What you see is pretty much what he got when he clicked the shutter: I didn’t have the impression that there’s a lot of post-production going on as the image travels from camera to print, through a computer, but I may be wrong about that. There’s a reception tonight at the gallery: 458 W. 28th St. 6th floor. It’s Moody’s first solo with VA. Should be fun.

September 28th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Untitled 2, Alexander Solomon

What looks like a tremendous show opened Friday at Manifest, including this great landscape from Alexander Solomon. I’m pretty sure we’re looking at a meticulously constructed diorama which the artist has then carefully lit and photographed. Hard to tell much more about it, and there’s very little information about the artist on the Web, but it looks superb on the invitational postcard I got from Manifest. Dioramas have become a fascinating branch of art, especially from people like James Casebere, Matthew Albanese, Amy Bennett and now, apparently, Alexander Solomon. (We had a photograph by Claudia Fainguersch, similar to some of Solomon’s, in a juried show at Viridian Artists not long ago.)

I must have done something wrong in a previous life, which brings with it a recurrent payback in this one every time I want to be in Cincinnati. It’s a city just barely too far away for me to get there more than once a year, if that. For me, it’s essentially as inaccessible as L.A., given the hours/cost required either on the road or in the air. Otherwise, I’d show up for every opening at Manifest, a little oasis of sanity and quality for artists around the world. Fallback position: I’m going to do some browser hunting of the artists in this landscape show to get a better look at their contributions to Vista.

On Mr. Solomon I could find only terse and/or cryptic comments he’s made about his own work. He appears to be a recent art school grad. What little I did find was interesting, especially his second observation below:

For any landscape, my goal is to make something sublime and unsentimental. To my mind, that combination tends to consist of pairing opposites.

I’m curious why I feel a compunction to coldly approach this kind of work and the fear of sentimentality that I’ve experienced throughout the contemporary art world.

For the viewer, I hope my work is like the cave in The Empire Strikes Back, “What’s in there?” “Only what you take with you.”

May the force be with you Alexander. Keep making scenes like Untitled 2.

There are impressive shots here, if you want a detail of this work (the scene is so amazingly rendered that I keep questioning whether or not I’m looking at something he constructed rather than an actual scene, but I’m sticking to my story. The silvery car helps.) Plus another similar scene, just as impressive, of a hill shorn of trees but ready for more depradation.

September 27th, 2013 by dave dorsey

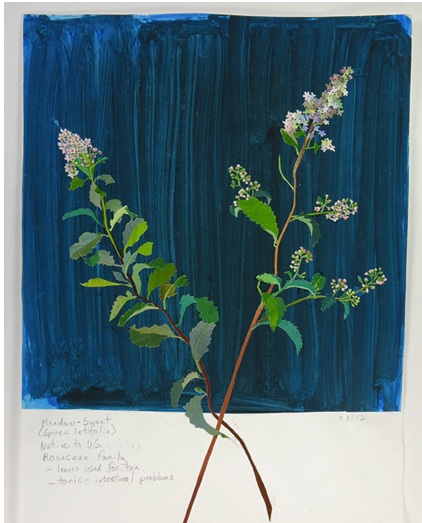

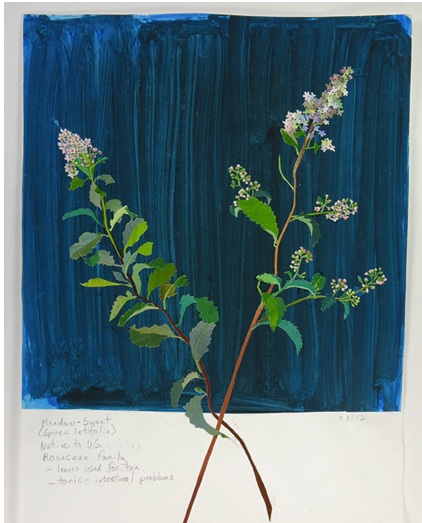

Meadow Sweet, Elizabeth Bisbing, gouache, paper, graphite.

Any artist who learns to work in a garden quickly recognizes parallels in the way a plant and a painting grow. It takes time and repetition: fluids (oh, don’t I know), light, and an interaction with random elements all play a role in both forms of creation. As I work with plants I’m constantly reminded of how I work with images: I get something started, I add more of this or less of that, and I prune away at whatever isn’t helping. And what I’m working on tends to grow more slowly than I’d like, requiring a lot of waiting otherwise known as patience. What you’re really doing is guiding, not creating. Looking at a nasturtium bloom or a ripe tomato, after sometimes months of husbanding the plant, can feel exactly as if I’m standing back and gazing happily at a completed painting. (I start dahlia tubers in January, inside the house, and step-by-step transfer them to potting soil and then sometimes larger pots before putting them outside in May or early June. Some even start blooming in the house in May. There are really only a few months I’m not tending dahlias one way or another–from October through January I keep them dormant in the garage.) So, more and more, painting an image of a head of lettuce or a dahlia strikes me as almost the final step in gardening itself. I’m actually just looking, studying, consuming with my eyes, the outcome of continuous labor and care over the course of more than half a year, in the case of the dahlias. And the act of painting one of these plants recapitulates the process of growing it. What I see is beauty, but it’s more than that. There’s always a hint of strangeness in natural forms, which is part of the fascination. Often I see something like what Michelangelo conveyed in his unfinished Captives, a wrestling with the constraints and obstacles of physical life–every flower and vegetable is, in some respect, at act of overcoming. The flowers that emerge twisted and deformed–qualities echoed in the complex form of a healthy dahlia, which has as many curving planes as a skull–can become just as fascinating as what seems initially more symmetrical and “perfect” in the healthiest flower. What comes through, in nature, again and again, is unity within complexity, how something with so many diverse parts can look utterly simple and coherent. It’s amazing to me that a dahlia can emerge from a shrunken tuber locked into the ground, as even enormous plants emerge from the tiniest seeds. I look past the beauty of a flower, amazed at how something like this, something this infinitely detailed, can emerge from the skin of that little brown lump underground, swell itself into fat stalks that sometimes rise seven feet into the air, get as large as a cluster of corn stalks, produce dozens of ten-inch flowers and then turn black in the frost and disappear. Paintings are like that flower at the peak of its cycle. You stand there, looking at it, thinking where did that come from? Seriously? How did that get made?

Many of these reflections and experiences influenced the way I appreciated Elizabeth Bisbing‘s exhibition of flower mosaics at Soho 20, late in the show’s run last week. (It closes in a day or two–I was late to a number of shows on this MORE

September 26th, 2013 by dave dorsey

The Secret Messages, detail. Gulgun Aliriza, oil on board

At Blue Mountain, Gulgun Alizira, a young painter from Turkey, has her first show with a delightful range of work, from quite large to extremely small. As in 4″ x 4″. Clusters of these tiny oils greet you as you walk into the gallery, and they held my attention the longest. At first they look like details from or studies for larger paintings, but they push Aliriza’s all-over technique into full abstract expressionism. In the larger paintings, there’s a tug-of-war between representation and paint itself, which reminds me most of Cecily Brown‘s more recent, less porn-y images where it’s even more of a “Where’s Waldo” hunt for the nude figure in the nest of brushstrokes. Here, the thicket of paint gets just as dense. In a studio scene, stretchers and props mix it up with furniture, and the room looks like what’s left after a tropical storm has blown out all the windows. It’s an interesting creative mess, both as a place to work and as an image of actual space. It’s all about making the paint a little more important than the rendering of a scene, and this comes through most dramatically in the tiny squares that seem to abandon representation altogether and where her areas of color become more coherent and powerful. I liked all of it, but the smallest work had the most charm. The paint gets really thick too in these tiny ones: folds and ripples of it rise up like peanut butter on a cracker. I told the sitter at the desk, “I’d love to see her duplicate one of those tiny ones, but on the same scale as her big paintings.”

September 25th, 2013 by dave dorsey

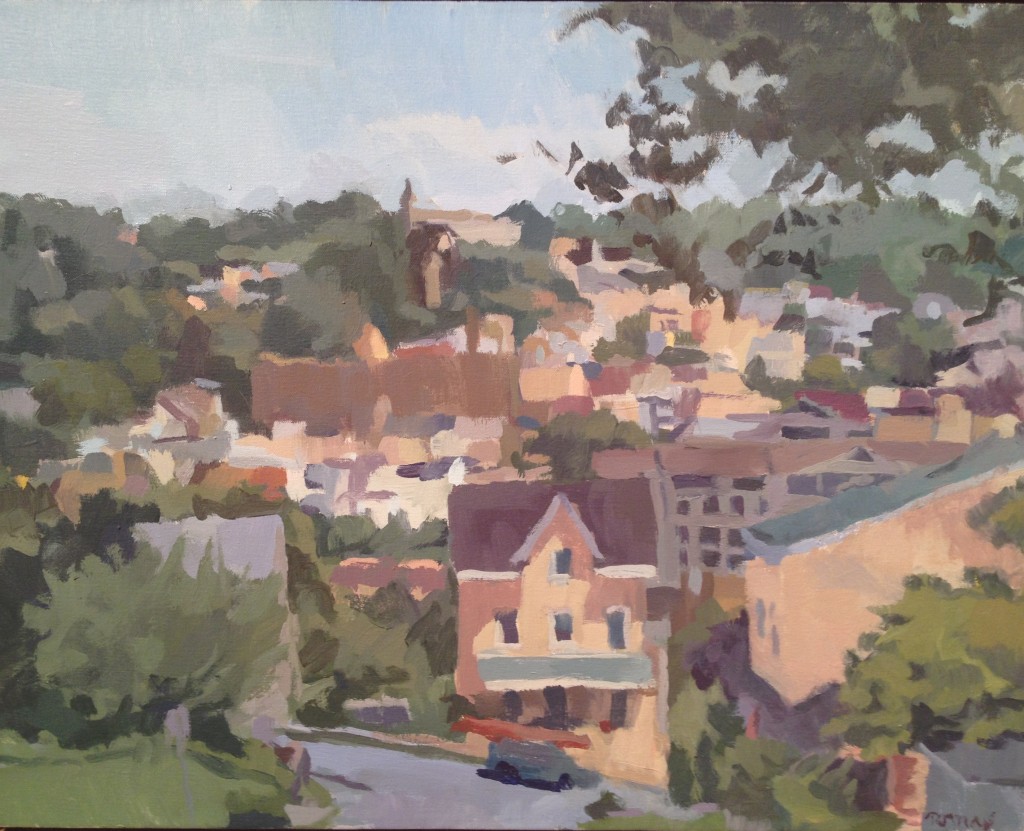

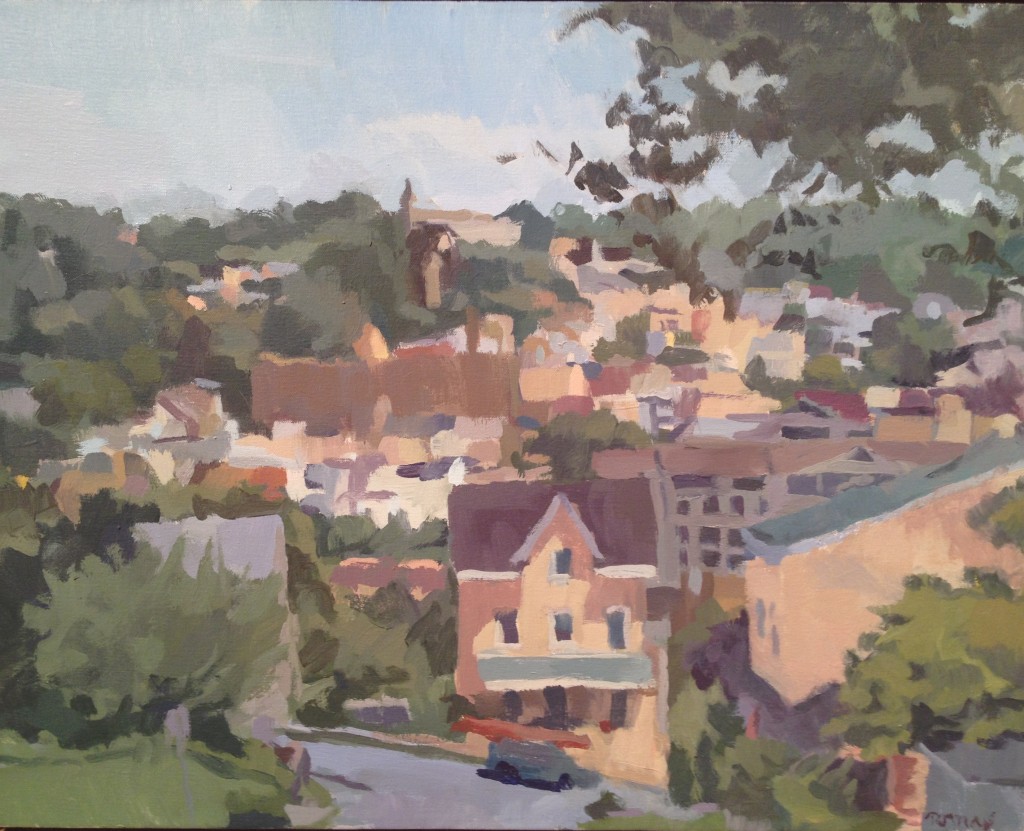

Belmont Hills, Ian Tornay

When I walked into the Bowery Gallery last week, I could have sworn the ghost of Fairfield Porter had been summoned to choose the current show. Ian Torney’s oils have internalized and absorbed a great part of what Porter achieved, and he has taken Porter’s intuitions and refined them into his own perfectly executed landscapes, still lifes, and the one self-portrait on view here. He works in the same mid-range of values, avoiding the brightest and darkest ranges of light and dark, muting his colors into effortless harmonies, evoking detail rather than rendering it—painting the light between objects rather than the objects themselves, as Porter phrased it. He does it all with seemingly unconscious ease: what others struggle for years to achieve and never attain. If art buyers were looking for genuine greatness, rather than simply a good investment, this show would have sold out. I think I saw only one or two red dots, even though these paintings were vastly underpriced. Buying art now must be a lot like choosing a college for your high school grad: just go to an art fair and look for the one that’ll pick the most money from your pocket. Anything that high-priced has to be the best, right? If you want to know what’s great about painting and what’s depressingly bad about the art market, take a look at Tornay’s work while it’s still up for the final days of the show.

September 24th, 2013 by dave dorsey

A Mixture of Frailties, Susie MacMurray

If you want to marvel at how rubber gloves and fishhooks can be turned into fascinating works of art, check out Susie MacMurray’s current show at Danese Corey. The gallery opened in a new location only a few weeks ago. I stumbled onto it last Thursday while walking past its large street-level windows on West 22nd. I was on my guard against the cool, impersonal feel of the show, which at first had the familiar white-cube redolence of chilly and cerebral, high-end formalities, but it won me over. It’s a beautiful show in a wonderful and much larger space than Danese used to occupy, and the place is perfectly suited to MacMurray’s spare, less-is-more constructions. The artist’s ability to create a sense of poised expectancy out of the most ordinary and humble materials is remarkable. She works in a repetitive range of shapes, using craft shop and household supplies: dollops and teardrops of wax, thin-gauge wire, hooks, hairnets, rubber kitchen gloves, air compressor hoses, and—my favorite—knitting pins. She returns again and again to a tight range of materials: fishhooks, wax teardrops and the knitting pins. In a few cases, her work reflects her previous career as a musician, such as the assembly of those pins  bearing what look like conical spinning tops made of wax. Arranged in dozens across one wall, they suggest, collectively, the lines and clefs of musical notation. These slight, long pins have small eyes, like skewer handles, which she pierces with her fishhooks bearing much larger dollops of wax. Rows of those identical dollops dangle in mid-air like topsy-turvy raindrops—or pendant earrings. Those pins, though, are alive. They bristle from a wall like acupuncture needles, arching as they seem to pull back against gravity.

bearing what look like conical spinning tops made of wax. Arranged in dozens across one wall, they suggest, collectively, the lines and clefs of musical notation. These slight, long pins have small eyes, like skewer handles, which she pierces with her fishhooks bearing much larger dollops of wax. Rows of those identical dollops dangle in mid-air like topsy-turvy raindrops—or pendant earrings. Those pins, though, are alive. They bristle from a wall like acupuncture needles, arching as they seem to pull back against gravity.

As in so much of her work, there’s an energy in the paucity of means. MORE

September 22nd, 2013 by dave dorsey

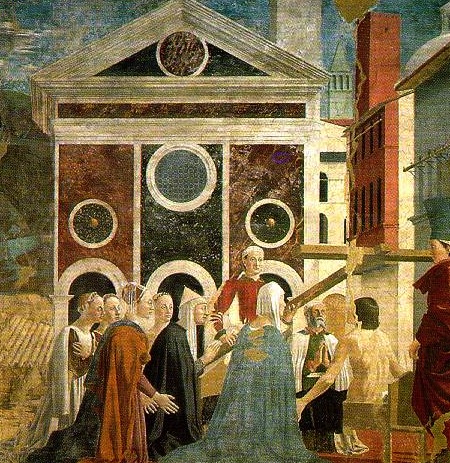

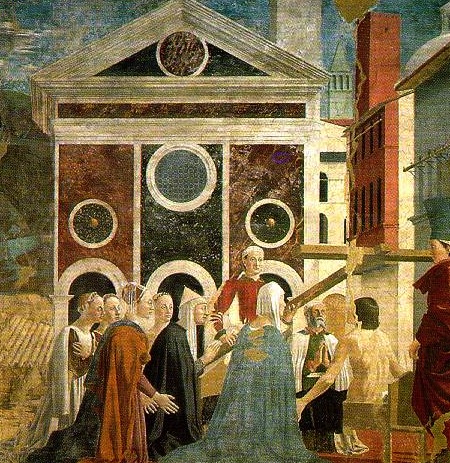

Finding and Recognition of the True Cross, Piero della Francesca

At Hyperallergic, a great essay on Piero della Francesca, who has become my favorite Renaissance painter. Much of Thomas Micchelli’s precision and eloquence in reflecting on this painting would have applied as well to Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels, where angels and architecture seemed to be echoes of one another and arrayed on a single plane, as well as figures standing within the illusion of a three-dimensional scene. Seeing it at The Frick was the opportunity of a lifetime, and I was so grateful to be there for the time I spent with it. Oh to be able to see The Dream of Constantine some day. Not likely. (You can get as good a view of it as possible here, without seeing the actual painting itself. That angel’s arm. Those stars above his wing . . .)

Also, I love the notion that “all art is contemporary” now, because, well, it is.

September 21st, 2013 by dave dorsey

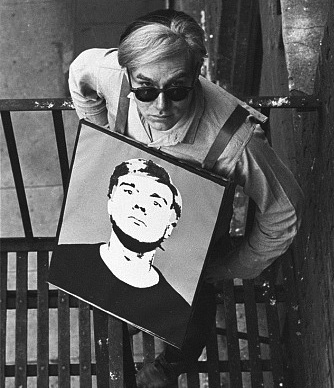

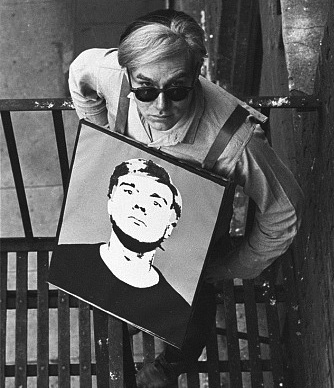

A Warhol sandwich

What could be more Warhol than a photograph of Warhol wearing a photograph of Warhol? Photographs by William Love Kennedy at Steven Kasher.

September 20th, 2013 by dave dorsey

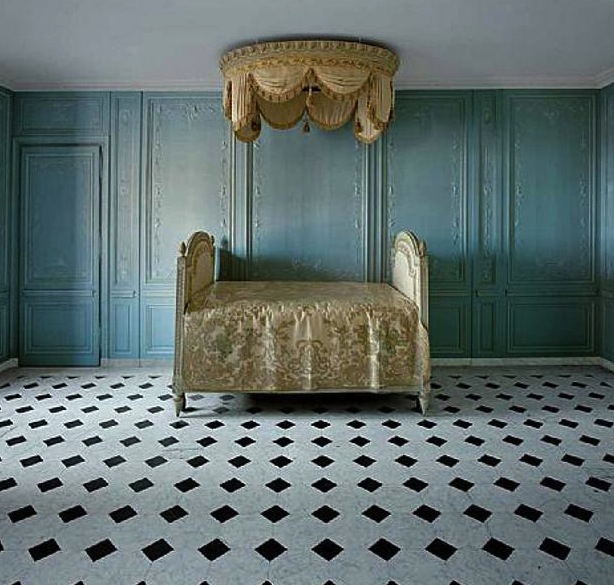

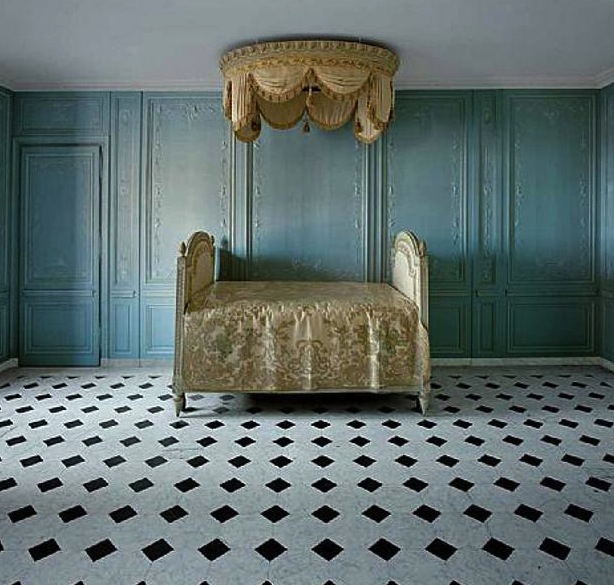

Marie Antoinette’s bathroom

Don’t say cupcakes. Cheap shot. All I want to know is, where’s the granite-topped St. James Vanity from Restoration Hardware? At Mary Boone, Robert Polidori’s photographs of Versailles. . . could there be a timelier show, all things historically considered?

September 19th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Cancun’s underwater sculpture museum

In Cancun, you have to go underwater to tour the Museo Subacuatico de Arte, or MUSA. It’s a museum that doubles as a new kind of coral reef: a haven for fish and people both. Nature and art become one.

“It’s the story of the three dedicated – nay, heroic – people who made the place happen. There was Jaime Gonzalez, a biologist and hard-nosed bureaucrat sickened by the damaged reefs in his country; Roberto Diaz, the entrepreneurial tour operator and closet artist who knows everybody in town; and Jason Taylor, the outsider with a new idea and the talent to pull it off. In all, it was a herculean effort. But eventually permissions and a little money came through and so Taylor started working in 2006. He makes the molds using plaster on the naked body and then adds the clothing later. Walking through a new dry-land exhibit of his work, he says he can name each of his models – from the young girl to the pregnant woman to the worker he flagged down in the street who was initially confused about what exactly this odd foreigner wanted to do. Even Diaz, who’s also an amateur sculptor, got into the game and created a statue designed from a lost picture of his grandmother. Today, with 470 statues, the museum is a huge success and one of the major tourist draws to Cancun.”

The goal: 10,000 sculptures over the next ten years.

How many works of visual imagination have ever required fifty years of labor? That’s how long Jerry Gretzinger has been working on his ever-changing SimCity-like map. Hey, you have to get it right if you want the citizens of virtual Ukrania to find their way around. Google maps won’t help, yo.

How many works of visual imagination have ever required fifty years of labor? That’s how long Jerry Gretzinger has been working on his ever-changing SimCity-like map. Hey, you have to get it right if you want the citizens of virtual Ukrania to find their way around. Google maps won’t help, yo.