Archive Page 5

November 24th, 2022 by dave dorsey

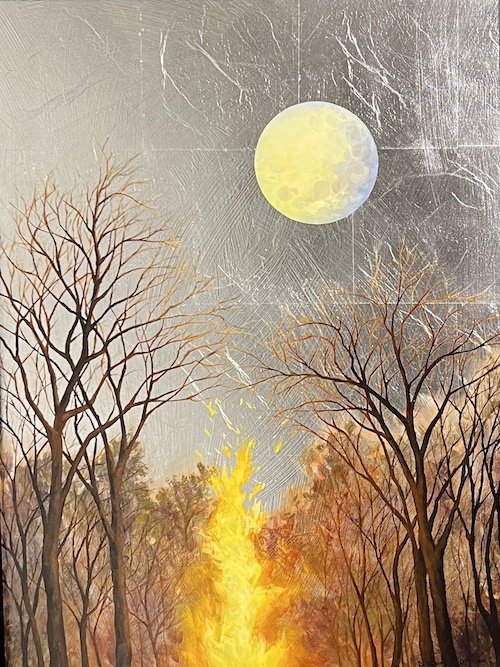

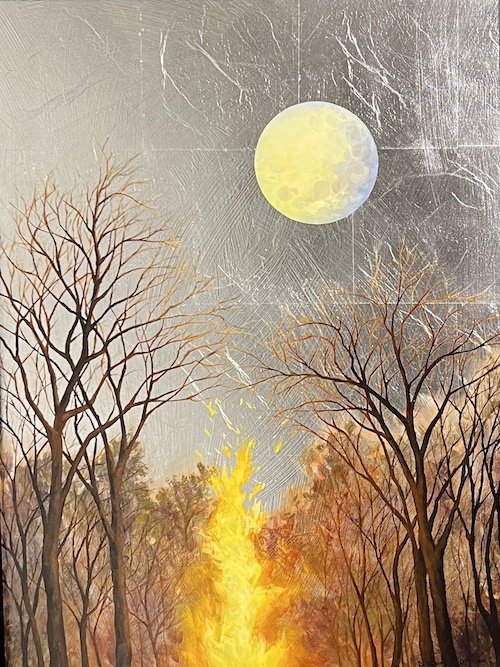

Bonfire Moon, Bridget Bossart van Otterloo, oil and silver leaf on board.

At Oxford Gallery many of the participating artists responded to the theme of the new group show—Spellbound, the Art of Mystery—with compelling work.

When I first walked through the gallery, I passed a welded steel raven from Wayne Williams with a cursory glance at the bird, but then on a second tour of the show, I paused and looked at it from various sides and began to absorb the dignity of the crusty, ruffled creature. It began to remind me just a bit of Donatello’s Lo Zuccone, a prophetic  interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible.

interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible.

Anthony Dungan’s large abstract acrylic on canvas, Saucerful of Secrets, almost side-by side with the raven, represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.

represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.

At first glance, William Keyser’s Inexplicable Lacuna appears to be a joyous pastel homage to a Matissse cut-out or one of Milton Avery’s women assembled with flat, simplified color. Yet it has a mysterious dark black line stamped MORE

November 21st, 2022 by dave dorsey

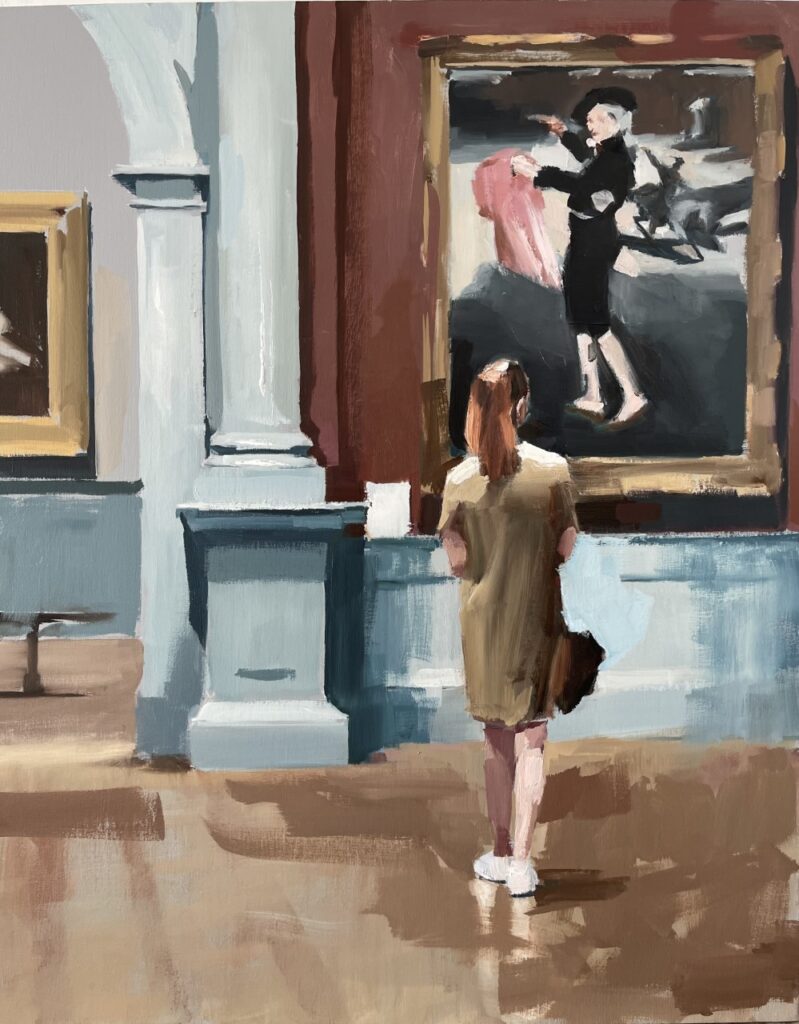

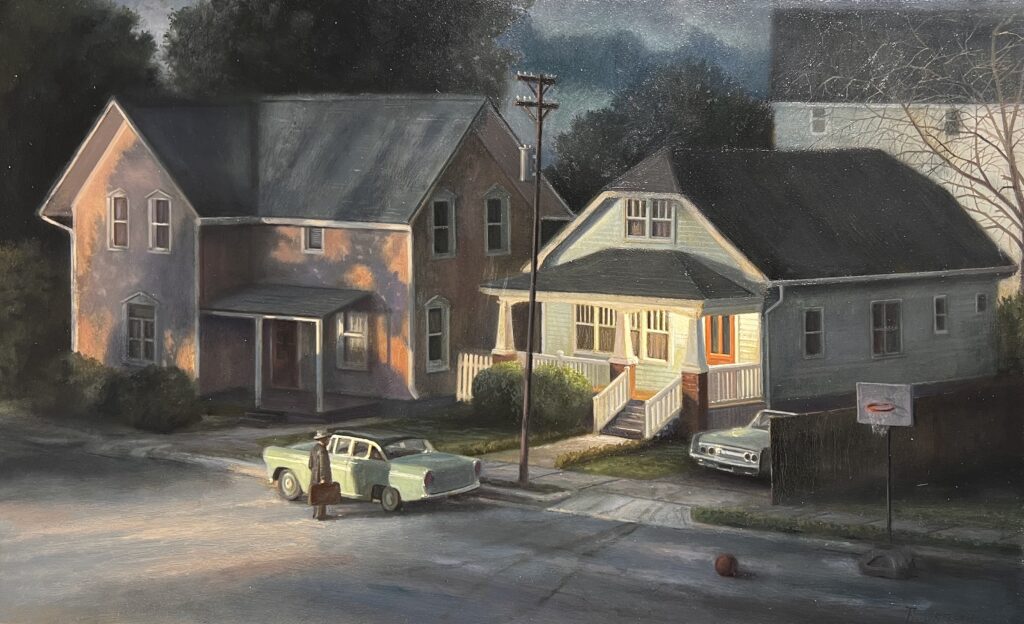

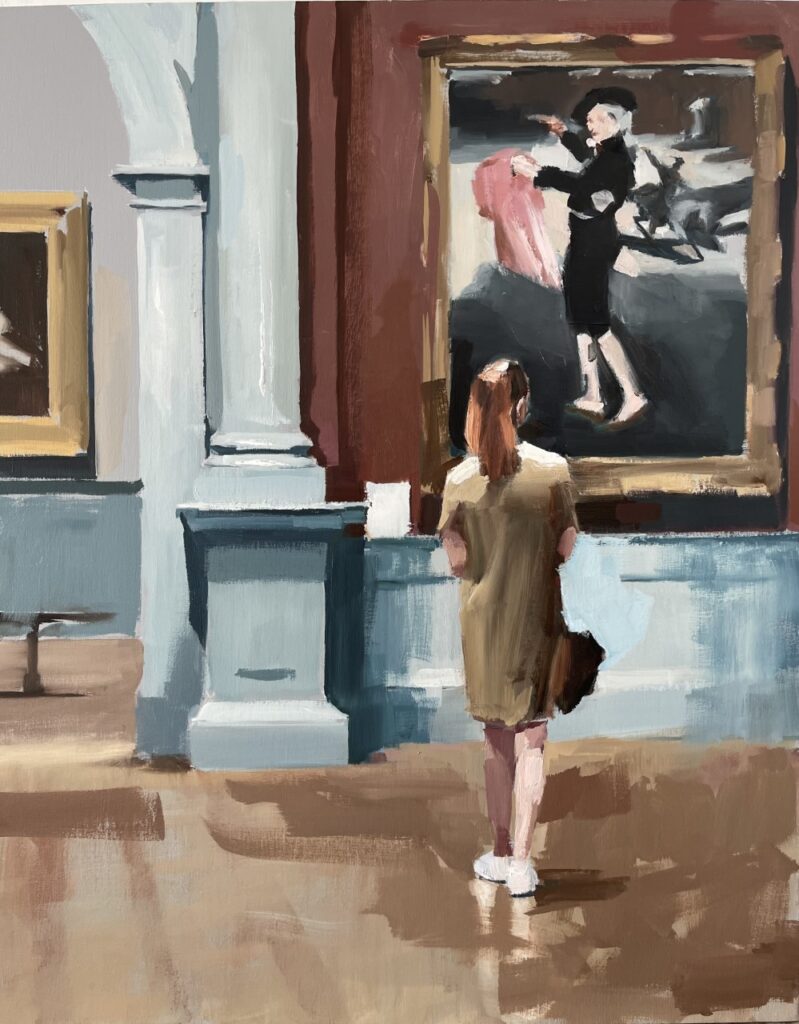

Mark Tennant

It’s a lovely candid moment, a young woman pausing to study a Manet at the Metropolitan. It’s one among a series of paintings Mark Tennant has done from what could be a field trip of female students milling through the museum. It seems to eschew his typically prurient or declasse subjects, a departure for Tennant whose metier is mostly a dour and slightly Calvinist glare that exposes the seamier precincts of human desire and behavior in depressingly raw terms. His subjects range from streetwalkers, cocktail parties that look like clueless celebrations in the eye of the social hurricane in the 1960s (or in Portland and Seattle, circa 2020), Zsa Zsa Gabor’s driver’s license pic, moments of drunkenness, public making out, many many exposed teenage legs going up and down stairs or posing in a variety of places that make them seem Spring Breakishly available for mischief, and a killer under arrest viewed in Gerhard Richter black-and-white. Most of these are photographically sourced from flash-lit freeze frames, offering him black outlines that push his figures forward. Much of it seems a dark celebration of the despised male gaze skulking at the edge of legality. What a relief to see a well-behaved girl tamed by the greatest of the Impressionists. But wait. Even here, if you try enough search engine queries, it turns out the Manet has a little transgender touch that pulls the knowledgeable viewer out of the comfort zone and into the present: Mademoiselle V in the Costume of an Espada. A young woman as matador, drag king in mid-19th century Paris. In his sly au courant way Tennant has stuck to his program: the notion of normality is a relic. It was on the wane already back then at the birth of modernity, when Manet’s nude enjoyed lunch on the grass with a couple fully dressed men. By contrast, the subject matter is what’s least interesting with Tennant, but it appears to bring him a huge following, a Pamplona stampede of fans if you check his Instagram. I suspect the seedier side of his imaginative home is a decoy. Like that pink cape, it draws you close enough for his brushwork to slay you. Those killer marks recommend him to anyone who paints.

November 18th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Drea Cofield, Mantis, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches, 2021

Drea Cofield’s more recent work has an idiosyncratic way of engaging visually with the natural world that brings to mind Burchfield and

Nick Blosser, though her work seems closer to the spirit of animation. Burchfield is one of the few non-Asian painters who have depicted cicadas, and not just the legs, wings, and thoraxes, but also their rattlesnake, high-frequency whine. Cofield does insects in an equally interesting way. There’s a charmingly Disneyesque but disquieting air to her praying mantises. Some of her natural scenes are simplified but exacting in the way they capture the light on the deformities of old trees in a drab unpicturesque acre of woods most painters wouldn’t give a second look. All of her current work departs dramatically from her earlier Day Glo caricatures of naked figures cavorting in strange ways in erotic fever dreams. In the image above, the vestigial naked figure is submerged, shimmering under sunlight filtered through the water’s rippled surface. You hardly realize you’re being mooned. Mostly, the new work looks outward at nature, from within the house of her style, to produce carefully observed images of what’s there in the world, not just in her mind, though her vision is a strong and simplifying filter. I’m sorry I missed her work in my visit to The Armory Show. Here’s her bio from Exeter Gallery, a Matt Klos joint in Baltimore celebrating its fifth year of operation (congratulations Matt) exhibiting mostly perceptual painters:

Drea Cofield has created a sensuous and saturated world in her new series of paintings for Soft Limbs. The series depicts the cycle of a day: sunrise, sunset, and night illuminated by cool lavender light. The show is on from Nov. 14th-December 31st. Come celebrate with the artist at a reception on Friday, November 18th from 5-7pm.

Drea Cofield is an artist currently working between Indianapolis, IN and Brooklyn, NY. In 2013, she received her M.F.A from Yale School of Art (New Haven, CT), and in 2008, her B.A from DePauw University (Greencastle, IN). She has exhibited in the U.S. and internationally including New York, Los Angeles, and Perugia, Italy. Most recently she exhibited in the Armory Show with 1969 Gallery in New York; solo exhibitions at the Tube Artspace in Indianapolis and DePauw University. Upcoming exhibitions include a solo exhibition at Exeter Gallery in Baltimore, MD. Her work has been featured in the Brooklyn Rail, Artnet News, Juxtapoz, Blouin Art Info, and in Suzanne Hudson’s latest issue of Contemporary Painting (World of Art). She is the recipient of an Elizabeth Greenshields Grant and the Yale University Gloucester Painting Prize. Residencies include the Guild of Adventure Painters SWAB Mobile Residency in 2019. She is the Founder and Director of Bomb Pop-Up, a pop-up Art & Music initiative that focuses on providing visibility in exciting contexts to emerging and established artists and musicians, working with over 200 artists from all over the world and collaborating with institutions such as the National Academy of Design. Cofield has been a visiting artist at Cooper Union, Pratt Institute, and a returning critic at the School of Visual Arts. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Art at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana.

November 15th, 2022 by dave dorsey

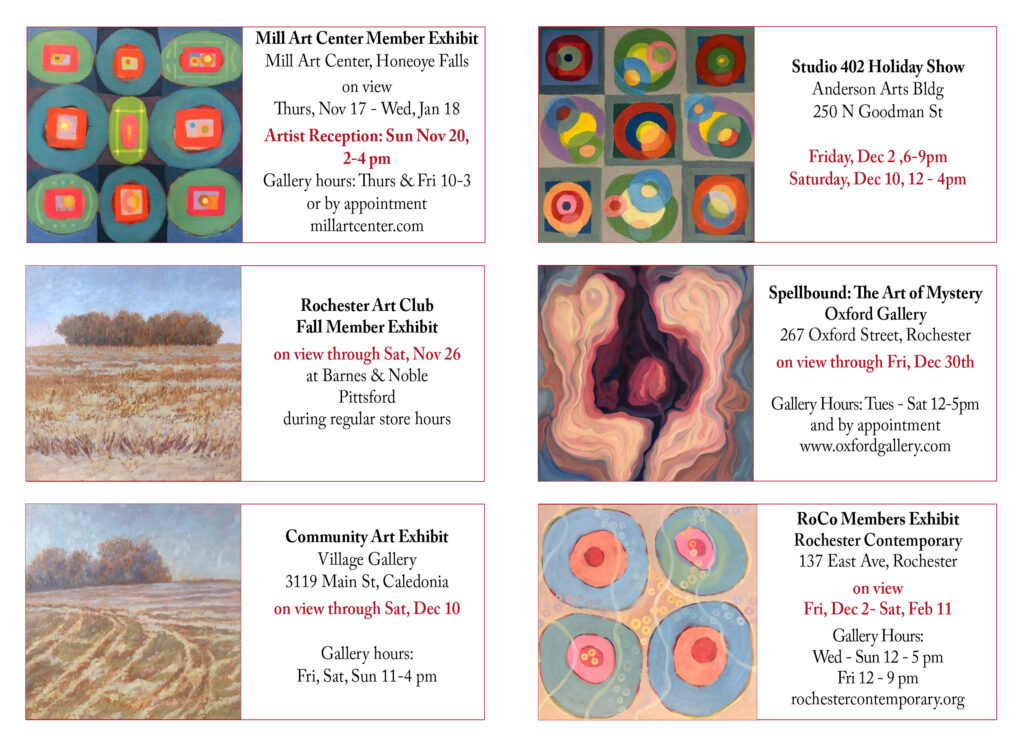

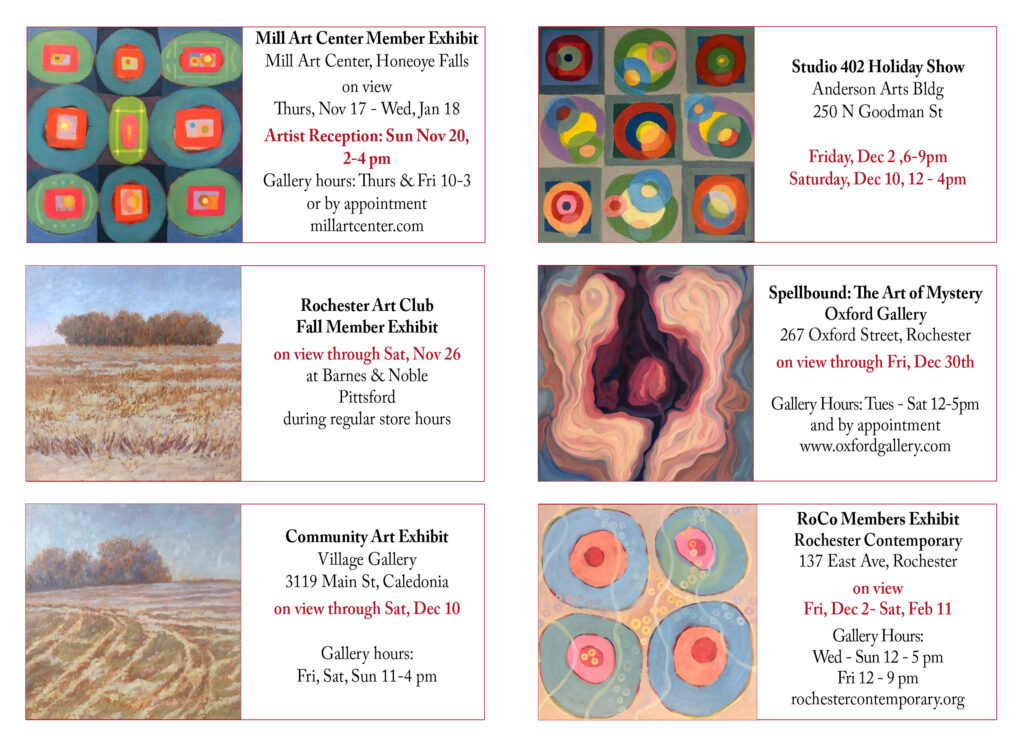

Above are multiple opportunities to see new work from Jean Stephens, including the current excellent group show at Oxford, Spellbound: The Art of Mystery. It’s well worth the effort to take a look.

November 13th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Here’s a pretty well-known quote in context. A part of the context is that it is from Selden Rodman’s book. The telling of it printed here is the most accurate that we’ve got, and perhaps this is relevant as I’m seeing it condensed or misquoted in memes often.

“You might as well get one thing straight,” he said, relaxing, “I’m not an abstractionist.”

“You’re an abstractionist to me,” I said. “You’re a master of color harmonies and relationships on a monumental scale. Do you deny that?”

“I do. I’m not interested in relationships of color or form or anything else. I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on — and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate those basic human emotions… The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point!” – Selden Rodman, Conversations with Artists.

November 8th, 2022 by dave dorsey

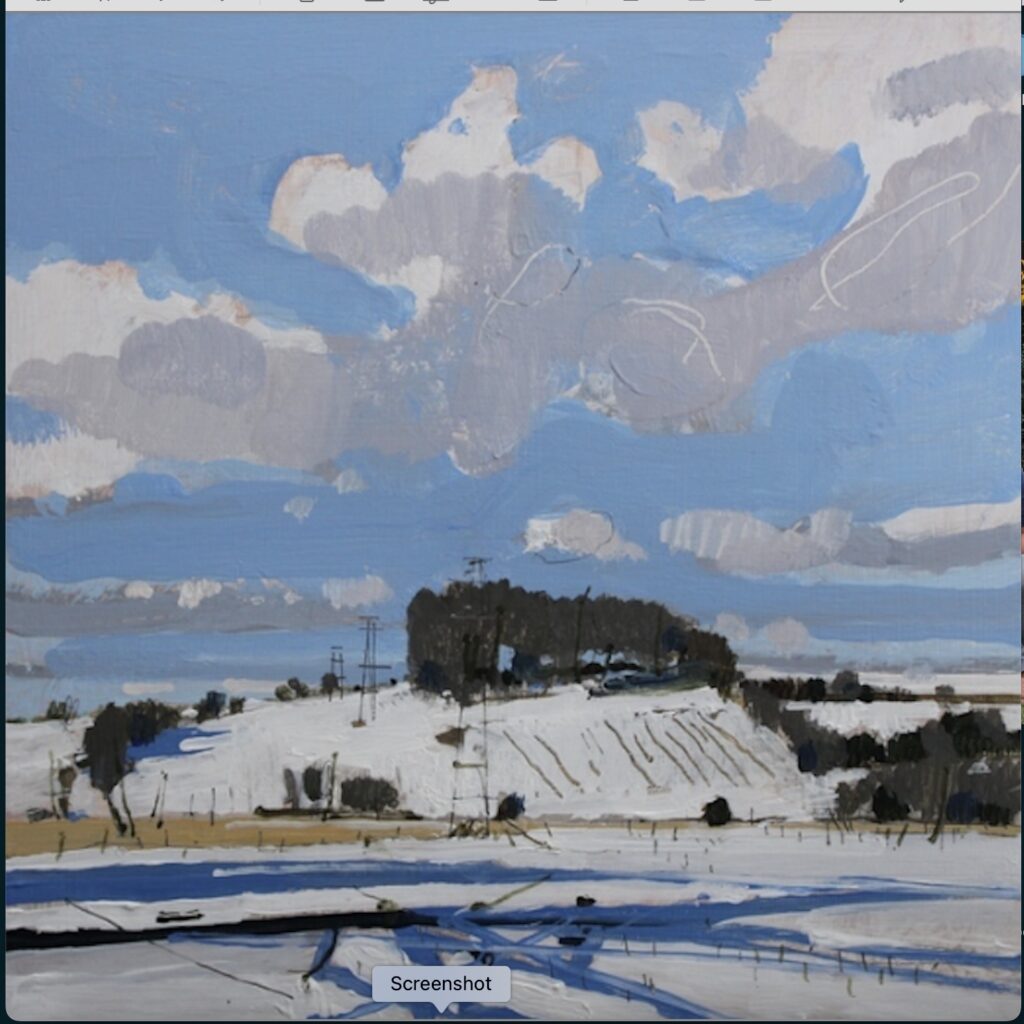

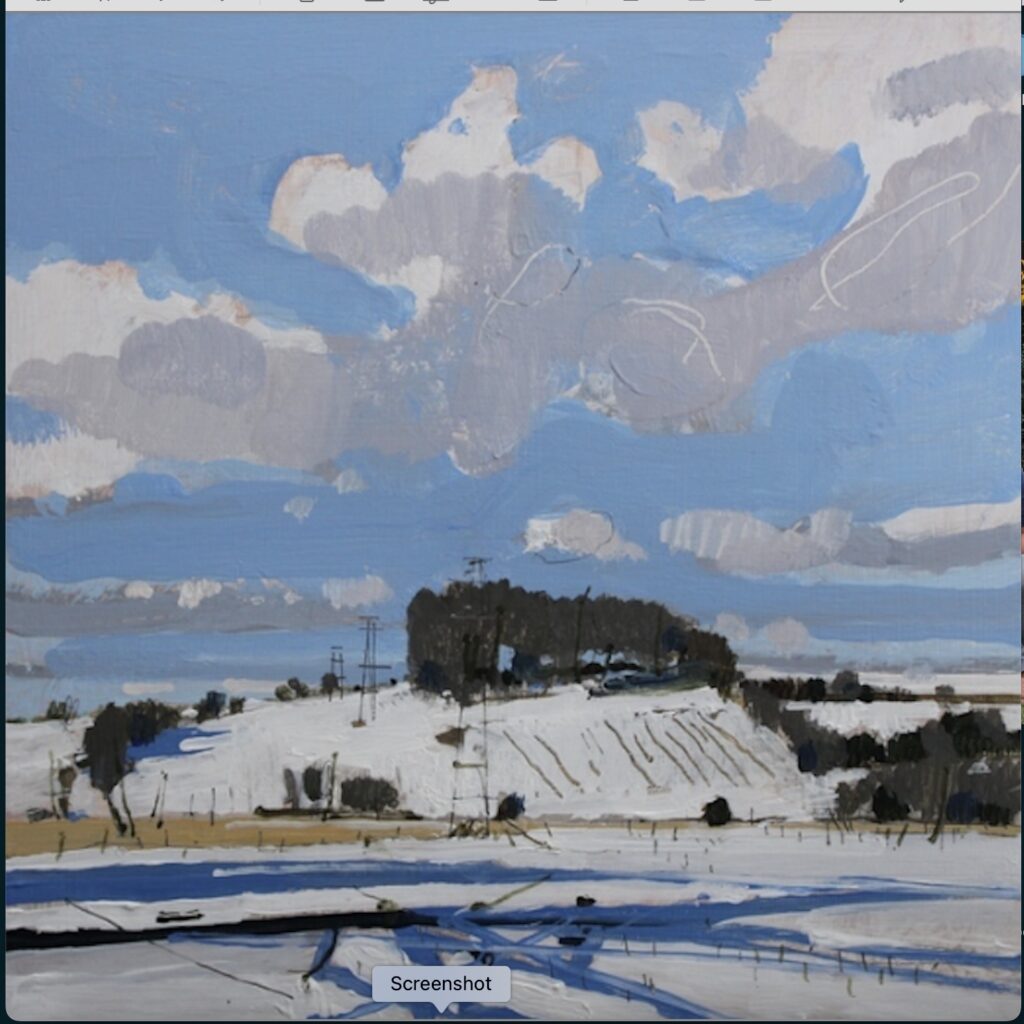

Harry Stooshinoff, 10 Saved Acres, February 20, Acrylic on birch panel

I hope Harry doesn’t mind if I repost most of his latest newsletter. Note his use of the word rubbish. So much of good art depends on chucking that particular quality out, especially prohibitions based on consideration of anything that diminishes the intensity of energy one applies to a painting. His letter is so full of wisdom and expresses so well what it’s like to try and maintain this creative energy in painting. My mom died in April and I’ve spent the past six months, in which I’ve had to pull away from painting quite a bit, thinking about what I want to do as a painter from here on, and I’ve been drawn toward several different paths, without actually getting back to daily work yet. Soon. But I’ve been wanting to work in several modes concurrently and this newsletter offers a lot of encouragement.

Harry talks about this kind of juncture directly. He advises that you do what energizes you, what you most want to see when you are done, not what you think you should be doing based on any other consideration–market, past work, reputation, what other people think, “branding”, whatever. What I admire in Stooshinoff’s painting is how it reflects two kinds of work I’ve deeply loved in the past: Asian art, especially Japanese sumiye painting and Fairfield Porter’s paintings in the 50s and 60s. I’m not sure he considers either of these major influences for his work, but it’s what I recognize through his work. In the background lurks Matisse of course, casting his enormous light-filled shadow, but you don’t get to him from Stooshinoff’s work except through Porter. Mitchell Johnson is another artist doing something very connected to this kind of painting, with Porter and Matisse as a backstory, but without the Asian element for me.

Harry works quickly, very quickly, premier coup, as Dickinson expressed it, and yet his use of value and color convey how light and form in landscape actually looks. That’s the marvel. He’s a loose painter, and you can often see pretty clearly how he makes his marks. There’s no attempt to refine the evidence of his hand. The application of acrylic flows off his brush in what appear to be spontaneous gestures, but if you drill down into the details you see some very straight lines, hatch marks almost as regular as Durer’s, and exacting precision everywhere, even if some of his hills are stylized, more like karst mounds in China. I don’t think you see this terrain in Canada, but maybe the humpy kames and eskers we have down here south of Lake Ontario are common directly to the north of us on the other side of the lake. That paradox, the marriage of generalized forms and gestural marks with visual exactitude where one area of value ends and another begins reminds me of the paintings Fairfield Porter did when he was clearly using photographs as sources. Stooshinoff works from sketches done immediately in response to a scene that strikes him as arresting. His work looks abstracted from the actual vision of a landscape, but it’s more a kind of involuntary shorthand without any pretensions: just a man working under the pressure of his passion to convey what he sees, with an urgency to move on to the next moment of looking. It isn’t some sort of transformation of what’s seen into something more interesting or valuable than an original glimpse of an actual hill with a clouded sky overhead. He just wants to be a conduit of what’s already out there, in his own quiet, quick way. Here’s his newsletter:

There really are 1000s of ways to make paintings. And I’m not just talking about the history of art and other people. There are 1000s of ways for YOU and ME to make paintings. Perhaps we think we paint the way we do because we evolved naturally onto this path, this style, and so this is our signature ‘style’ that is somehow essential to our artistic quality and integrity. That may or may not be true, and mostly I think it’s untrue. Artists have been fed lots of rubbish through the decades that, for the most part, they have internalized. Whatever artistic path we stay on is a choice, and it’s a choice we make every day. You can wake up tomorrow and make a different kind of picture. Keep in mind that for years artists feared that their dealers might say something to this effect, “….you look like you’re all over the place and jumping around too much…keep within this style that you’ve made popular and that you’re now known for”. Hmmm…branding, and all that. Again, there is some good sense in this sentiment. Sometimes it’s obvious when an artist is not committed enough and is simply flailing in multiple directions. But, the inverse is so evident as well. Artists should not harness themselves in too tightly, for market reasons, or any other reasons.….if the need is felt, there is always room to explore more, in style, method, direction, or subject.

MORE

November 1st, 2022 by dave dorsey

Reverie #5, Bill Santelli, arcylic on paper.

One of Bill Santelli’s recent pieces on paper: he’s doing what I’ve been hoping for years he would do, building a composition without his typical geometric partitioning. Small work, on paper no less, but it offers the sense of a cosmic view, though it also gives me the impression of looking skyward at night or gazing up through water toward the surface in a colorful reef. And, on top of that, the image seems to map inner states in a 60s way. Marvelous.

September 14th, 2022 by dave dorsey

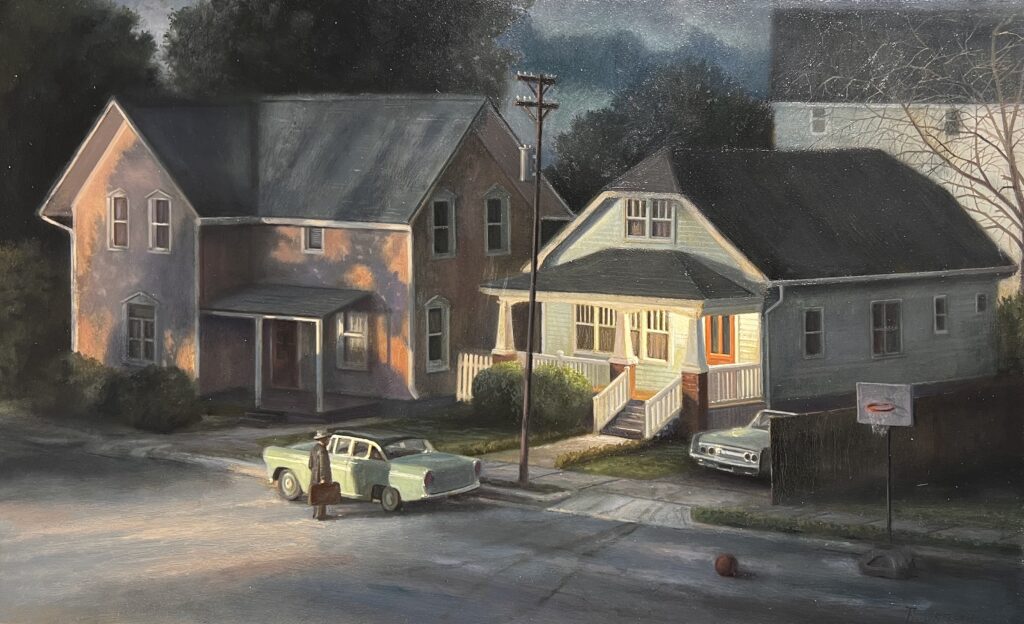

Landlord, oil on panel, 16″ x 26″

It’s hard to believe it’s been more than a decade since James Casebere’s photography was included in the Whitney Bienniel. I remember, back in 2010, being wowed by his reproductions of the suburban dioramas he painstakingly constructed and then lit and shot. His work seems to have gotten more austere and cerebral and political since then, but his landscapes of newly-built suburban dream homes still convey the ambivalent beauty of an increasingly unaffordable American Dream. Casebere centered the simplicity of his scenes at the median point between verisimilitude and minimalist geometry of newly constructed McMansions. His houses stand on an otherwise almost naked slope with newly-planted saplings a quarter century away from offering privacy and shade. Anyone who has lived in a new suburban tract knows the mix of feelings: the exhilaration of moving in, the weird sense of emptiness and exposure in a place without foliage, the smell of new construction and the sounds of new doors clicking into place, as well as the paradoxical solitude of tract housing jammed side by side into narrow lots. Casabere’s dioramas were about American life, as it is experienced by those lucky enough to buy a home—how much more poignant now in the current real estate market these scenes must be for young people hoping to put down roots. Yet his houses jutted up in various colors, evoking geometric abstraction, like the structures in an Icelandic landscape by Louisa Mattiasdottir. It was stunning work and it stirred many conflicted feelings—yearning, hope, and the inevitable disappointments of routine.

He was one of those art stars of the moment, using dioramas to make two-dimensional images, like Gregory Crewdson, on an even larger scale, whose constructed scenes—far more realistic and detailed—have a cinematic power and a darker, but even more alluring mood. Crewdson lives on the edge of popular culture. There’s a sense of epic effort in his illusions that seem imbued with an invisible presence. Built by hand and then captured with photographs, his work would be familiar to anyone who listens to Yo La Tengo (where I discovered it on one of their album covers) or watched Six Feet Under. His art was mentioned on the show, and he was recruited to do a promotional campaign for it.

It’s been years since I’ve looked into diorama art, so it took me a while to even come up with Casebere’s name, MORE

September 12th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Le bapteme, Marc Padeu, 78″ x 110″

On Saturday, I wandered lonely like a cloud through The Armory Show, at the edge of Hudson Yards. That domineering real estate venture is the child of our precarious finance-driven economy. It’s a forbidding, crystalline, Antarctic Fortress of Solitude rising up along the river, with Dubai-like heights so reflective its towers almost disappear against the sky. Across the street, a honeycomb of gallery booths spread out in uniform ranks inside the equally glassy, tourmaline facets of the Javits Center. (By contrast with the glass towers, the Center looks more like an enormous multi-story greenhouse.) Inside, at this annual pop-up art mall, rows of booths gave birth to another seemingly endless grid of tight little alcoves as I slowly made my way through the maze, swiveling my head in all directions, trying not to miss anything, as if riding through Pirates of the Caribbean.

The beautiful people were there in abundance, trying to look as chill as the champagne in ice buckets beside their plush chairs. So much money, but how much of it was being spent? I don’t know the break-even point for a gallery—how much needed to be sold to make a profit after the fee for a booth—but few of the people staffing these booths looked light-hearted. Most had a selection of work from their roster, while quite a few staked their investment on a solo show of only one artist. The solo shows were invariably the most interesting.

The free market is a necessarily brutal place, even at this lofty level. A corner bodega probably has an easier time turning a profit than many of the souls who must spend months preparing to ship this costly work overseas and put it up for sale at a fair. Represented were 250 galleries from around the world, but after an hour of walking, it felt like far more. It was often depressing, so much of it a cavalcade of disposable and over-hyped art. But that isn’t far from the experience of walking through Chelsea and ducking into one gallery after another. New York City is changing and has been for many years now. I miss being able to wander into Danese-Corey and never being disappointed. I miss OK Harris downtown. I also miss the Half King. And Hi Fi in the East Village. And the lines outside the Upright Citizens Brigade on 26th. All gone. Fine, so one is a restaurant, and another is a little bar/music studio, and another a school of improv, but they are similar disappearances of the past decade and were small bastions of quality or history or what will probably be considered Old New York in only a few years. Manhatttan needs another Maeve Brennan or Joseph Mitchell to document this metamorphosis, this infiltration. You feel as if you’re watching from the shore as art rides the froth of a giant wave of international money sweeping aside graceful little figures who managed to stay vertical on economic swells of smaller, more human dimensions. (There are notable survivors, like Arcadia Contemporary, whose scale is in all things extremely human. It didn’t need a booth at this show, because it is killing at its SoHo location, having sold out its entire new show at the opening on Thursday.) So it can still be done, old school, if the goal is to make enduring art rather than spectacular profits.

MORE

August 11th, 2022 by dave dorsey

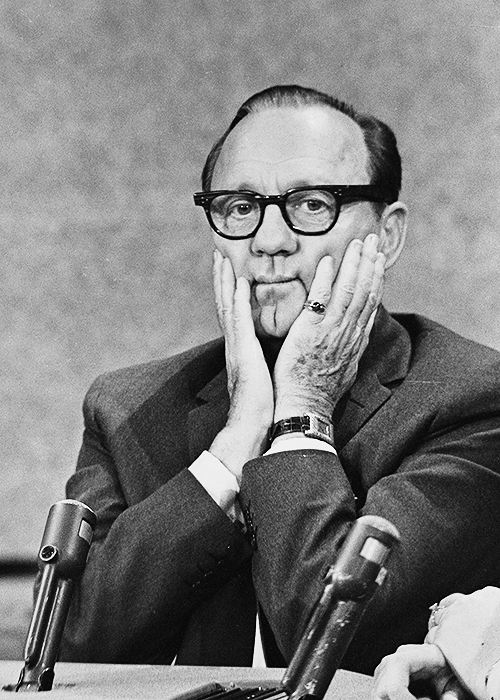

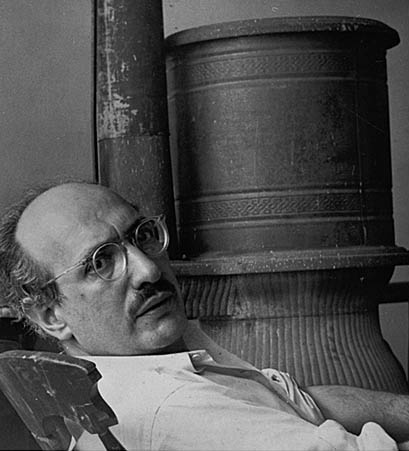

Dave Hickey, 1940-2021

In The Invisible Dragon, Dave Hickey argues for the unruly vitality of the human imagination against forces of control—economic, political, and academic. It’s a book that wants art to be made in a state of absolute individual freedom, where forms and ideas contend for survival in an imaginative free market governed by nothing but desire: the desire to make art and the desire to see or own it. It’s an energizing book. Though it’s a bit of an invitation to anarchy—creative anarchy—ironically, it’s an argument for deference and courtesy. He elevates beauty into a core principle, which hardly sounds scandalous, though it was greeted that way. For him the struggle to make something beautiful forces an artist to cede power to the viewer—the artist has to beguile, not lecture. That’s a shift in power that few people around him wanted to see. He asserts a painter needs to make the viewer want to look, rather than rely on institutions that compel people to look and think a certain way, based on certain forms of approved expression. Better to make a beautiful object without significance than to create an admirable bit of agitprop that repels or bores everyone who sees it, as it offers a dose of permissible opinions about life.

Yet rereading this book again, one can see how Hickey never thought to follow his impulsive invocation of beauty (in response to a question at a professional conference) with a journey to its Platonic extreme and see beauty as the mysterious goal itself. He doesn’t pause to attempt the impossible that every real philosopher has: what is beauty, in and of itself? The question is unanswerable, but craving an answer to it is an essential way to be awake to life. It’s a question a bit like Heidegger’s question of Being: “why is there something rather than nothing.” The first time I read his book, this avoidance on Hickey’s part didn’t really occur to me, this shunning of questions about the nature of beauty. It’s easy to miss how he degrades beauty, in a sense, as something almost equivalent to advertising. His point here was to fight back against external controls over creativity, and he succeeds, with supple, showboating eloquence.

He’s a relativist, a pragmatist, a postmodern theorist himself pushing back against how postmodern theory has been debased with political agendas. He argues that beauty is the most effective Trojan horse for smuggling ideas into the heads of others. If you’re a progressive who wants to see social change, then you need a David to paint something as visually thrilling as the Oath of the Horatii and secondarily deliver some politics, on the side, while he has you transfixed. Beauty is the gift wrap for provisional, historically useful ideas—yet the real gift for Hickey turns out to be the wrapping—and this is where he has to cede that beauty matters more than any significance you can consciously invest in it—because most ideas have an expiration date, while great beauty endures. MORE

August 4th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Sam King, Untitled, 10″ x 8″, oil on linen and canvas

That’s a sample of the work from Sam King on view at Manifest in Cincinnati right now, a fantastic little painting, with tremendously restrained color harmonies and a rich feel for the texture of his medium. It grabbed me in the email announcement Jason Franz and crew sent out inviting people to click into a conversation (see below) among the current exhibitors at Manifest. King’s work tends to follow the structure of this one, serried ranks of marks, though sometimes with a far more aggressive palette, visual jazz improvisations. He has worked mainly with unevenly mapped, loose grids of geometric shapes densely packed, honeycombed almost, into often tight formats: 15″ by 15″ canvases aren’t uncommon. Then, as you scroll through his site, he springs a very large image on you: 72″ in one dimension. Check out the paintings he did over the past couple years, breaking out of the grids though they are still implied so that the variations and the violations from those regular ranks of marks spring out at you like a Matisse cutout. Note the ones where he limits his color scheme and mutes it, or pares the colors down to a few with blocks of uniform color that look like redactions. The one above gives off a strong whiff of Klee and holds up well in the comparison. In this one the colors are exactly right, as if he’s translating a melody perfectly into paint for the first time, everything just where it should be on the surface.

The Zoom conference Manifest will be worth a listen. I’ve participated in one of these with Manifest and another, quite recently with fellow exhibitors at Main Street Arts. In both cases, it was a rich learning experience and rewarding to listen to fellow painters and those working in other media talk about how they work and how they came to be artists. Here are the details for joining the Zoom from Manifest:

Thursday, August 4th, 6-8pm

Common Ground #18 — A Virtual Exhibiting Artists Panel Talk

A Zoom-based loosely-formatted panel talk featuring many of the artists showing in Manifest’s newest set of exhibits.

Panel conversation prompts will include:

1. How is the notion of “transformation” evidenced in your work?

2. Considering materials specifically – At what point are they transformed into something you’d classify as art? Does the artist transform the materials or is it the other way around? Who else is allowed to participate in that conversion?

3. Do the products of your studio lead to more personal, inter-personal (artist to viewer, or vice versa), or community metamorphoses?

This pandemic-inspired format for artist talks at Manifest provides the public a chance to meet more exhibitors from the very wide radius that Manifest’s shows draw from. It also offers the artists from afar a chance to meet each other, our staff, and others in engaged conversation. It is also a particularly good opportunity for students of art at any level to have a chance to join in open discussion with working artists, and get a sense for how such a professional practice may be maintained and incorporated into one’s life.

This talk will feature the artists with work included in the newest set of exhibits of Manifest Gallery’s 18th season. It has been thanks to the heroic commitment of exhibiting artists that we’ve been able to continue our work as the neighborhood gallery for the world through the pandemic. However, what has been lost to some degree is the vital energy of people gathering at our opening receptions, and artists traveling to Cincinnati from near and far to make connections and meet each other in their shared exhibits at Manifest. We are offering this ongoing series of online panel talks to provide a chance for the artists and the public to share this common ground once again.

Tickets are FREE!

In order to help Manifest’s staff manage the online event we ask that anyone planning to attend register for a ticket. Zoom connection details and access portal will be provided as part of the ticket. Get a ticket at: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/378319663297

July 8th, 2022 by dave dorsey

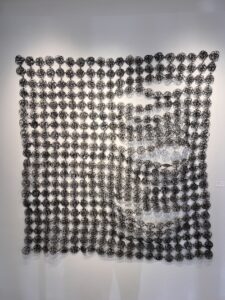

Tangible Things, invitational group show at Main Street Arts, Clifton Springs

Main Street Arts invited me to show some of my taffy paintings in its current exhibit, Tangible Objects, along with the work of six other artists who are experimenting with form and materials, and whose work in many cases evokes commonplace, overlooked objects. In other words, Bradley and Sarah Butler recognized that someone who tries to bring forth the sense of a world in a couple pieces of salt-water taffy would be right at home with these others: all of us are exploring the formal opportunities afforded by the most humble, vulnerable objects most would consider insignificant. In other words, the spirit of still life painting hovers throughout the show: the beauty and resonance of the everyday, domestic, and mundane. I was also delighted to see my sense of being haunted by color field painting (in my candy paintings) is echoed a bit in the work of one of the other artists, Myung Urso, whose materials are fabric and paper. It’s a great show, and the work is original, surprising and often quietly poetic and stirring.

Becca Barolli, weaves stiff, annealed steel wire into shapes that suggest fabric—an old, falling-apart afghan, a long muffler—bending the wire and braiding it into these nearly immovable effigies of something far more warm and cuddly. She works long hours, rubbing CBD oil into her fingers at the end of a work day, trying to weave with steel—it’s almost a vocation the Greeks would have imagined as karmic justice for some offense against tunics. The objects suggest petrified remains of what once nurtured  comfort and life, but they aren’t morbid, nor depressing. Instead, the immense, repetitive effort, the meditative devotion required to transform the body of supple, humble things into art gives them a mysterious totemic after-life. The contrast between the delicate, original object, and the work based on it, impervious as chain mail, accentuates the gap between the medium and what it represents as well as the delight triggered by that gap in all representational art, fusing both sameness and difference into one perception. Barolli is a recent MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and has had a residency at Mass MoCA and has shown at galleries in L.A., New York City and San Francisco. Her practice favorably brings to mind Susie MacMurray’s, and it would be interesting to see them paired in a show some day.

comfort and life, but they aren’t morbid, nor depressing. Instead, the immense, repetitive effort, the meditative devotion required to transform the body of supple, humble things into art gives them a mysterious totemic after-life. The contrast between the delicate, original object, and the work based on it, impervious as chain mail, accentuates the gap between the medium and what it represents as well as the delight triggered by that gap in all representational art, fusing both sameness and difference into one perception. Barolli is a recent MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and has had a residency at Mass MoCA and has shown at galleries in L.A., New York City and San Francisco. Her practice favorably brings to mind Susie MacMurray’s, and it would be interesting to see them paired in a show some day.

At first, Sue Blumendale’s dresses look as if they could be worn to a party, but they’re made of archival copy paper that serves as a support for digital images of people from her ancestry: mother, father, aunts and a grandmother she never met. The dress becomes a sort of sculpted image of an absent human form, missing from inside the dress but commemorated with two dimensional images printed on the paper. The pictures of her family come from a family album. It’s intensely personal and felt, and the humble quality of the dresses has an almost Japanese quality of self-effacement, the everyday object surviving, transcending its wearer, coming into its own, and likewise, the artist herself withdrawing to let the dress shine, just as the subject, the missing person is absent inside the dress but present in the memorial pattern. It’s the transformation at the basis of all art: the individual human being sublimated into the creation. These are wonderfully realized three-dimensional images, where stylistic choices come together perfectly in a unique way. It’s lovely, intensely personal work. One wonders if someone could make a living doing cloth versions of these dresses to be worn, on commission, for people who wanted to clothe themselves with a memory. A new form of portraiture and a new line of clothing that exhibits the work anywhere, at any time.

MORE

June 10th, 2022 by dave dorsey

I have never finished reading Frank Stella’s Working Space, a long and impressively written essay on the evolution of “pictorial space” in Western painting. It’s done as a coffee table art book, with lavish illustrations, so reading is optional. For a while, I loved listening to him talk about art, but early on I decided to get off the train at the nearest stop because I gathered what appeared to be its destination: positioning his work in the ongoing history of art. It’s a fascinating argument, because Stella can be a spell-binding rhetorician. His prose draws you in with its magisterial command of art history and his unique position as a pioneer in painting back when it was still possible to be such a thing. I suspect he has never gotten over that—who could? —and this book struck me as his attempt to characterize his entire body of work as pioneering. The book is bold, brilliant, and sometimes baffling, but I didn’t mind that last part, because his slippery prose has rewards of its own. That’s how rhetoric works: it draws you in with its momentum. He seems to be arguing for his later three-dimensional work, on shaped canvases, as a new way of painting “pictorial space” comparable in its paradigm shift, historically, to the intimate, cinematic depth of field Caravaggio brought to painting in his own time.

I don’t know. Aren’t Stella’s constructions more of an idiosyncratic fusion of painting with sculpture? I love his ebullient, affirmative energy, no matter what he’s doing. So does he need to cling to his pioneer status, especially when “progress” in visual art exhausted itself in the 60s?

Along the way in Working Space, though, Stella says things, in quasi-poetic idioms, where he finds brief, profound ways to veer out of his swim lane. It’s hard to tell if he knows he’s no longer talking about space or the depiction of space, but about epistemological quandaries fundamental to human life, not simply in the art of painting. Without warning, he slides into a passage about the limits of human knowing, the limits of knowledge itself, not just whatever is the case with things shown or signified. It’s evocative language that seems better delivered in stanzas than paragraphs. The italics are mine:

This ephemeral quality of painting reminds us that what is not there, what we cannot quite find, is what great paintings always promise. It does not surprise us, then, that at every moment when an artist has his eyes open, he worries that there is something present that he cannot quite see, something that is eluding him, something within his always limited field of vision, something in the dark spot that makes up his view of the back of his head. He keeps looking for this elusive something, out of habit as much as out of frustration. He searches even though he is quite certain that what he is looking for shadows him every moment he looks around. He hopes it is what he cannot know, what he will never see, but the conviction remains that the shadow that follows but cannot be seen is simply the dull presence of his own mortality, the impending erasure of memory. Painters instinctively look to the mirror for reassurance, hoping to shake death, hoping to avoid the stare of persistent time, but the results are always disappointing. Still they keep checking. We can see Caravaggio looking at himself from The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, Velásquez surveying his surroundings in Las Meninas, and Manet testing the girl at the bar to see if there is anything different about those who have to work rather than see for a living.

Stella bears down on something fundamental to human experience at the start of this passage: the way in which knowledge MORE

May 30th, 2022 by dave dorsey

I’ve been delinquent for quite a while now on this blog and Instagram, painting and not posting, much of the time, though for the past four months, I was also caring for my mother who died in April. I’ve also been awaiting the completion of a new studio, I was away from painting since early February. In the past four years I’ve chosen to spent nearly a near away from painting to be more with family members who were ill or at the end of life, so my work on the salt water taffy series has been slower than I’d hoped. That personal era seems to be over, and the new studio is almost entirely set up, so work resumes this week. I hope to return to this blog on a regular basis as well. It isn’t that I haven’t had things to say. As I like to remember Jack Benny’s punch line: “I’m thinking! I’m thinking.” It isn’t quite the way he phrases it in the bit, but you get the idea.

I’ve been delinquent for quite a while now on this blog and Instagram, painting and not posting, much of the time, though for the past four months, I was also caring for my mother who died in April. I’ve also been awaiting the completion of a new studio, I was away from painting since early February. In the past four years I’ve chosen to spent nearly a near away from painting to be more with family members who were ill or at the end of life, so my work on the salt water taffy series has been slower than I’d hoped. That personal era seems to be over, and the new studio is almost entirely set up, so work resumes this week. I hope to return to this blog on a regular basis as well. It isn’t that I haven’t had things to say. As I like to remember Jack Benny’s punch line: “I’m thinking! I’m thinking.” It isn’t quite the way he phrases it in the bit, but you get the idea.

May 30th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Dark Waters, Renato Muccillo, 6″ x 8″

Remarkable new paintings by Renato Muccillo at Arcadia Gallery. Very small, intensely realistic, yet painterly.

May 6th, 2022 by dave dorsey

eclipse, oil on linen, 12″ x 18″

One of the first shows I visited when I was in New York City last week was a meaning made of trees, a collection of new work form Ron Milewicz. It’s outstanding. Milewicz continues to explore the pictorial possibilities of his new location in the Hudson Valley. I had an illuminating conversation with him about the work.

1. The little catalog available at the show, first of all, how was it done? I’ve tried that for solo shows in the past and have not been happy with the results, but your images were accurate and well printed. Who did these for you? Second, the catalog was from your previous show? If so, there’s a real consistency in quality and approach between those paintings and the ones on view now. You have found a groove and are working it, and you have clearly defined personal “rules” you follow in these Arcadian views. Did this style come to you all at once, full blown, or in stages?

The catalogue is from my Axis Mundi show in 2020. It was printed by an online company called Uprinting. I had the paintings photographed professionally. I designed the catalog myself on my Mac using Pages, and then a graphic designer familiar with Uprinting design programs made the layout that was sent to the printer.

That was two shows ago—I had another show since at Pamela Salisbury Gallery in Hudson, New York, in 2021.

I do not have “rules” but I do have a consistent approach to the landscapes that has developed over the past several years. For a period of about two years, I was only making on site graphite drawings. These tonal works are very much a direct response to the experience of the landscape I am working from—its atmosphere, light, spaces, and forms as well as its stillness and calm. The drawings were a very intuitive reaction to the environment, and they came relatively quickly. I then started to make oil paintings in the studio from the drawings. It took a longer time to understand how the drawings might be reinterpreted as paintings, in terms of materials, touch, color and scale.

2. Your career is interesting: you’ve gone from excellent urban landscapes to these visionary woodland scenes, both periods just as well done, but with a completely different sense of purpose, at least for the viewer. The urban landscapes fit within a much broader practice for contemporary artists; many more people are working in that vein these days. What you are doing with the trees reminds me of Burchfield and Nick Blosser, a Tennessee artist who has almost disappeared from view on the Web. Do you see these as two distinct phases or is there a continuity between the city and the country work for you?

They are two phases as they are derived from distinct locales and from the very different circumstances of my life outside of the studio, which inevitably changed my priorities in the studio. There is continuity in the sense that I am painting the world around me in both instances, although the conditions of those worlds are very different from each other. There’s also consistency in my concern for light, stillness and formal rigor.

3. I think of Burchfield in particular: the disjunction between his dark, almost monochrome American Scene pictures and the nearly psychedelic visions of his last period where he seemed to be attempting to convey the totality of nature in each painting. The divide between those two periods was radical, more radical than the shift in your work, but there’s no way for me to see how you get from the urban landscapes to the woodland visions, step by step. The move to Hudson Valley obviously triggered something, but the question is: what internally changed in how you see and paint as a result of this move? Did you grow up immersed in nature and then left it behind for years working in New York? MORE

March 31st, 2022 by dave dorsey

It’s There in The Humming Air, Bill Santelli, acrylic on canvas

On a quick visit to Bill Santelli’s studio last week, I saw a recent painting that knocked me out. In my Instagram post about it, I touched on some of the things that really work and give it a sense of natural depth, as if I’m seeing an actual scene in nature, with a slightly altered mind, as it were. There’s a shape that reminds me of a sunflower and the tendrils of paint reminding me of sprouts—I called them fractal rivulets in the post. The presence of white space, and the shape it assumes throughout the image, has a very kinetic unity and tension. I love the relief of white space in any abstract—and the shape the total white space assumes, sort of rearing up in the center of the painting—the way it sets off highly saturated color and offers a respite, a bit of emptiness that plays off the intensity of what’s going on around it. It really works here. The diagonal lines, in sets of three, on a bias, rather than a balanced grid, also contribute to the sense of energy and movement and surprise.

Bill: It’s called It’s There In the Humming Air. I think I did talk to you about this. I was going to do this other painting, and it’s the first time I’ve painted over something. Underneath it was a painting of the bones of a church I took a picture of in Washington DC. It was like a Jehovah’s Witness or something, not a cathedral, a glow coming out of the windows as we drove by. It was a blurred shot I took as we drove by. The painting never got going. Then you and Bill and I were at Bill’s house and we were talking about painting over stuff and I said I had this painting and I was going to paint over it. There was an outline of the church, so that’s why there’s the slant.

That has a lot to do with it: the asymmetry of the three lines and three here, so that it brings your eye up to the upper right corner. And it has a lot of white in it. This has a lot of white compared to what you usually do.

B: That’s a good remark, that’s what I was feeling. I got over here and there wasn’t much of the underpainting of that church and there’s still an outline here of a window and I was thinking this needs something different and didn’t want to keep going with the red and the yellow, so I went with white.

It looks so much like enamel, not acrylic. Like the Alkyd paintings of the color field painters.

B: Some of these acrylics are glossier when they dry. We’ve had this conversation ongoing, the whole idea of hard-edged painting, getting rid of the personal connotation in the title. I was saying last time we talked I’ve been thinking of this other series of hard-edged painting with no subject, just color.

Just improvisation. And that’s what I do with the taffy. I’m not trying to say anything. I’m just getting it to work formally and by the time I’m done, this is a field with the sun over it or it has some other resonance. I don’t start out trying to express anything definite.

B: It’s so interesting, I’ve been watching videos of Bryce Marden, one is an interview at the Tate Gallery and another is a lecture he gave in conjunction with the show. He’s articulate. He was talking about numbers and the importance of the numbers, and rules, and how he approaches painting. I’ve been marveling at the surface of his work. He said it’s a process of mixing turpineol, the oil paint and beeswax. The paintings never really dry. He goes back over the surfaces to level them off with palette knives or whatever.

February 18th, 2022 by dave dorsey

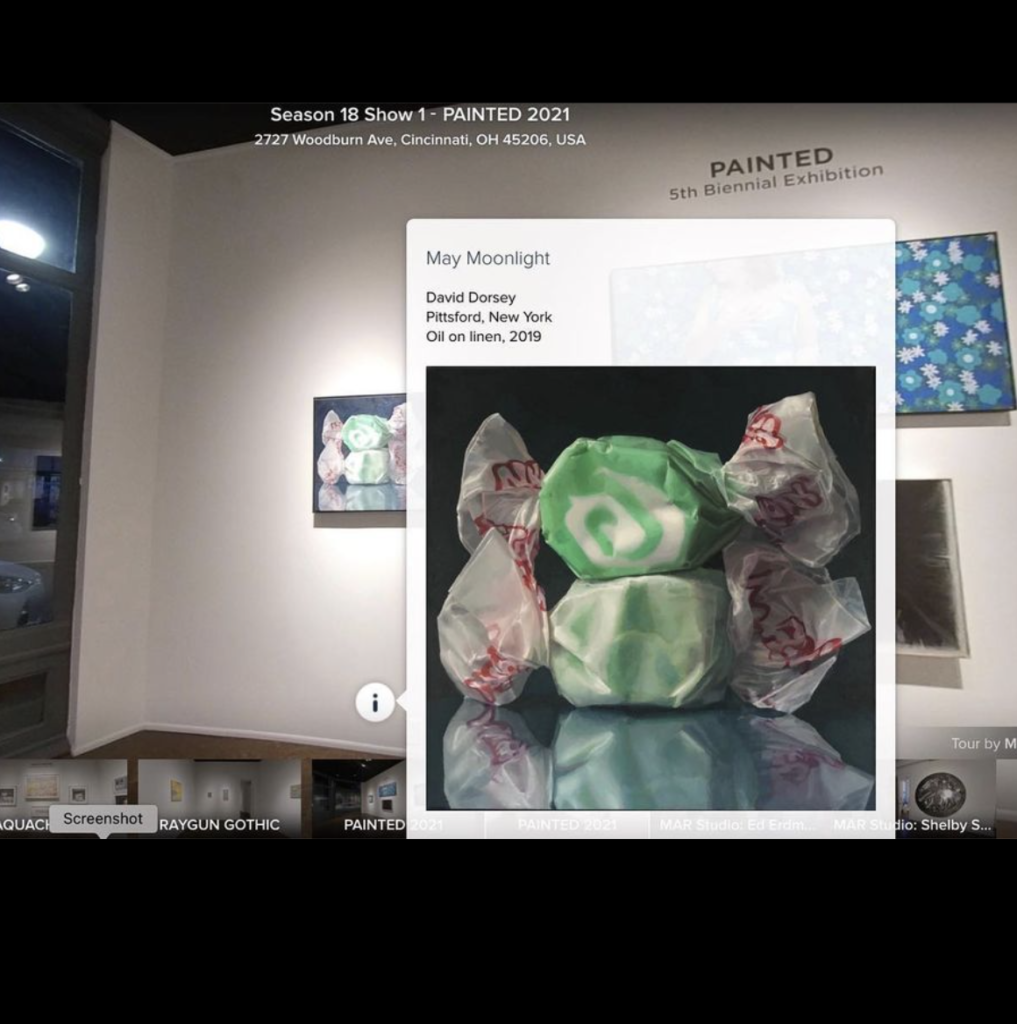

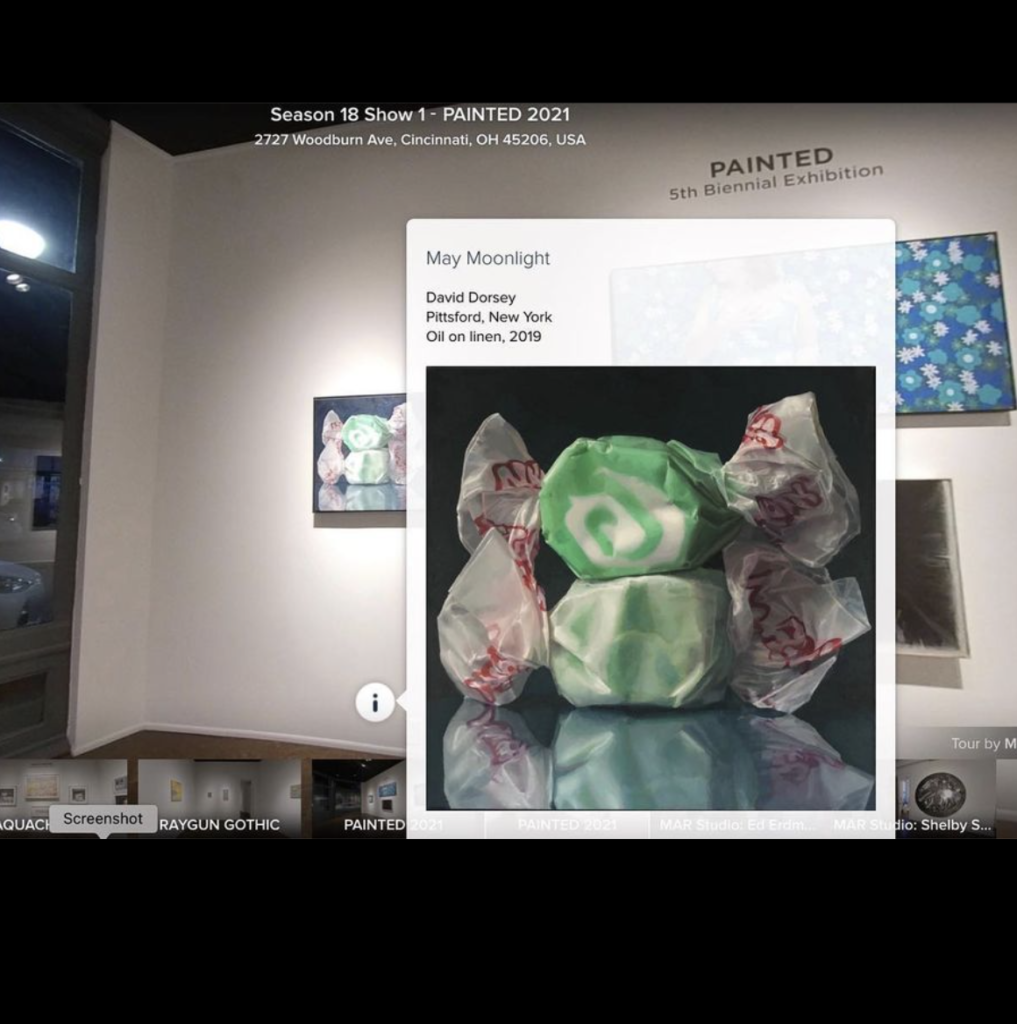

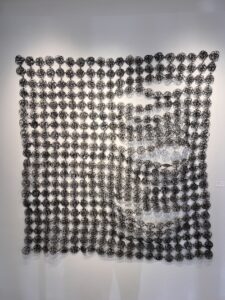

A screenshot from the online tour of Manifest’s Painted exhibition.

While the Painted exhibition was still running at Manifest Gallery, in Cincinnati, late last year, I participated in a Zoom conference with around a dozen artists whose work was chosen for Painted and the gallery’s other concurrent exhibitions. It was fun and humbling, because some of the other artists were conversationally eloquent about their work and art in general, while I felt bashful and halting by comparison. After more than a decade of writing about visual art, you would think I’d have been an open spigot of confident opinions, but that isn’t how it felt. Adam Mysock, Education and Studio Program Manager at Manifest, moderated the conversation. Of course, some of it was inevitably about what the artists were trying to achieve in their work. What they intended for their work to do for a viewer. How the work was the outcome of purposeful intent and had designs on a viewer’s perceptions, ideas, emotions, and so on. Later in the online conference, Mysock asked a question that got crickets from the participants: “So is it possible to imagine an entirely passive way of painting?” I thought at the time it was a question worthy of the sort of strenuous meditation a Zen adept brings to a koan and was especially pertinent to anyone who works with photo-realistic methods as I usually do. I couldn’t think quickly enough on my feet, partly because it’s subtle and complicated and a little paradoxical. The question has continued to haunt me and only recently have I realized I should have at least said that whole issue is central to what I’ve always sought to do in representational work.

Most people, including painters, think of style—the signature of the painter’s heart in every detail of the finished work—as the essence of the work’s originality and value. So the way in which an artist distorts, shapes, censors, simplifies, or translates what he or she sees into a unified image establishes the value of that particular painter’s work. This would appear to be an entirely active process: the outcome of complex, continuous choices as the picture is being painted. At some point, Fairfield Porter said something that probably wouldn’t be repeated by most painters now, but it’s a simple way to imagine what even photographically accurate painting actually does: to depict the world, just as it is, while making it a little more beautiful. It sounds like a recipe for the equivalent of sentimentality: trying to make the world more beautiful than nature did. But that isn’t what he meant. I think he was talking about how the process of transforming natural vision into a painted image mysteriously reveals the beauty that’s there but unrecognized in what a person looks at but doesn’t really see every day. How that transformation occurs is the essential mystery of the whole pursuit. Porter simplified what he saw, reducing a wealth of detail to one or two strokes of paint in some cases, made countless choices to eliminate aspects of what he saw and alter a color here or there, or everywhere, for that matter, to harmonize it with others on the canvas. He made active choices that had some conscious or subconscious end in mind, his goal or purpose, even if that purpose was merely to complete the work in a way that enabled every little part to be indispensable to the work’s visual unity. It would seem to be an intensely active, not passive, process.

But he was hoping that his work would do nothing more than capture “the light in the room” just as it was, the moment in time and place, even if much of what the light revealed to his observant eye gets lost in its resolution into paint. His painting of tennis players has that quality of being exactly how the court looked just as one of the players served the ball, the bright mid-day light intensifying the whites and flesh tones, deepening the darks of the shadows behind them, even though most detail was erased in the way he applied his paint. There’s no purpose here other than to convey the entire experience of that moment, and he succeeds in such a way that you can smell the air and feel the warmth of the sun on the backs of the players. In that sense, what he’s doing is utterly passive, honoring a simple, trivial moment in all its vitality and beauty and order. His paintings are an homage to this sort of mindfulness and humble appreciation of the mostly unregarded glory of ordinary life, from hour to hour—as were the paintings of Vermeer and Chardin and most of the Impressionists and the perceptual painters now. And most landscape painting in general. In other words, he worked as part of a long tradition very much still alive now.

For the record, over the past year, I’ve become interested in art that does just the opposite. MORE

January 30th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Giuseppe Celi, Still Life and Things, 2005

oil on plywood, 32×32 cm

January 27th, 2022 by dave dorsey

Head with Fabric, David Baird, Birmingham, Alabama Oil on canvas, 2020

David Baird had three paintings in Manifest’s Painted exhibit to kick off their 18th season in Cincinatti. This one, Head with Fabric, has many of the fine qualities of his painting, Red Nude, that just took First Prize at the Salmagundi Club’s New York Figurative Show. His handling of paint in the way he renders a figure reminds me a bit of Degas, which is high praise: the soft glow and gradual transitions among tones without being obsessive about detail while conveying the living quality of flesh–his figures breath. You feel you can take their temperature. But what makes his paintings so astonishing is the variation in level of verisimilitude, moving from persuasive illusions to flat patterns and roughly unfinished portions of canvas without destroying the overall feel of space and depth. Diarmuid Kelley has been doing this, to a lesser degree, for a while now, but without creating as much interesting tension between the finished/unfinished, illusionistic/flat areas of his canvases. It’s something Baird has in common with other painters who have connections with the Jerusalem Studio School. Some of Baird’s still life objects work both as fuzzy abstract areas of tone and as soft but utterly convincing visions of objects in three-dimensional space. The color is usually a range of rich, gorgeous earth tones worthy of Braque. It’s hard to figure out precisely how he does it. That usually wins my highest respect, when the technique seems utterly impossible to reverse-engineer.

interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible.

interloper, in from the cold, out of place in polite society, but also just where he ought to be. Titled Nevermore Evermore, it’s ostensibly an homage to Edgar Allen Poe but it’s even more an admiration of the huge bird itself, with its sentient eye, poised and observant, sizing up the entire gallery from his corner. What struck me most deeply was how little Williams consciously imposes himself on the steel he brings alive—his ideas, his opportunity to call attention to his stylistic prowess. He gives you the raven as it is, an intelligent, even playful genetic sibling to the crow, its aggressive shifty cousin. Anyone who knows birds has mixed feelings about the larger corvids. Yet I once worked at a desk beside a woman who kept a pet raven and called herself a “raven maniac” largely because her bird was always playing games with her, enjoying control of air space in her home, pilfering small objects from various rooms and hiding them in the cushions of her couch. Wayne Williams’s raven could easily be a portrait of her bird, a haughty touch of mischief in the eye, with a lack of urgency in the pose suggesting wisdom or at least wise-guy confidence. When I asked why the feathers seem to rise up in relief at the tips, like old roofing shingles, Williams told me this is how a raven’s feathers behave, unlike a crow’s. Williams takes the world as he finds it and gives it back to you in a way that makes you see it afresh and just as it is. This isn’t a Leonard Baskin bird, nor a bird used to campaign against the world as Ted Hughes employed his crow, but an actual bird as mysterious and complete as the world itself, with a title that offers a choice between utter despair and the possibility of hope. It’s a work of deep appreciation and representation, the artist disappearing into what he has created: everywhere present but nowhere visible. represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.

represents a new benchmark in his painting. His best work in the past has been built around abstracted but evocative human figures where the sensuous curves are incorporated in such a way that they take you by surprise when you recognize the silhouette: working as both abstraction and representation. Here representation has been almost abandoned, though the three spheres suggest celestial or planetary visions. Mostly they work to create tension between their exact circumferences and the ruptured, richly colored grid. The riot of brushwork seen through black louvers looks like a distillation and concentration of an upstate autumn but also suggests a psychological or emotional cauldron. You see all that energy trying to burst through, but safely locked behind black bars, both hidden and disclosed.

comfort and life, but they aren’t morbid, nor depressing. Instead, the immense, repetitive effort, the meditative devotion required to transform the body of supple, humble things into art gives them a mysterious totemic after-life. The contrast between the delicate, original object, and the work based on it, impervious as chain mail, accentuates the gap between the medium and what it represents as well as the delight triggered by that gap in all representational art, fusing both sameness and difference into one perception. Barolli is a recent MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and has had a residency at Mass MoCA and has shown at galleries in L.A., New York City and San Francisco. Her practice favorably brings to mind Susie MacMurray’s, and it would be interesting to see them paired in a show some day.

comfort and life, but they aren’t morbid, nor depressing. Instead, the immense, repetitive effort, the meditative devotion required to transform the body of supple, humble things into art gives them a mysterious totemic after-life. The contrast between the delicate, original object, and the work based on it, impervious as chain mail, accentuates the gap between the medium and what it represents as well as the delight triggered by that gap in all representational art, fusing both sameness and difference into one perception. Barolli is a recent MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and has had a residency at Mass MoCA and has shown at galleries in L.A., New York City and San Francisco. Her practice favorably brings to mind Susie MacMurray’s, and it would be interesting to see them paired in a show some day.

I’ve been delinquent for quite a while now on this blog and Instagram, painting and not posting, much of the time, though for the past four months, I was also caring for my mother who died in April. I’ve also been awaiting the completion of a new studio, I was away from painting since early February. In the past four years I’ve chosen to spent nearly a near away from painting to be more with family members who were ill or at the end of life, so my work on the salt water taffy series has been slower than I’d hoped. That personal era seems to be over, and the new studio is almost entirely set up, so work resumes this week. I hope to return to this blog on a regular basis as well. It isn’t that I haven’t had things to say. As I like to remember Jack Benny’s punch line: “I’m thinking! I’m thinking.” It isn’t quite the way he phrases it in the

I’ve been delinquent for quite a while now on this blog and Instagram, painting and not posting, much of the time, though for the past four months, I was also caring for my mother who died in April. I’ve also been awaiting the completion of a new studio, I was away from painting since early February. In the past four years I’ve chosen to spent nearly a near away from painting to be more with family members who were ill or at the end of life, so my work on the salt water taffy series has been slower than I’d hoped. That personal era seems to be over, and the new studio is almost entirely set up, so work resumes this week. I hope to return to this blog on a regular basis as well. It isn’t that I haven’t had things to say. As I like to remember Jack Benny’s punch line: “I’m thinking! I’m thinking.” It isn’t quite the way he phrases it in the