Erin Wozniak

One of the first place winning paintings from Erin Wozniak, in the Manifest INPA4 competition/publication. The painting is astonishing enough, but even moreso when you see how small it is.

the painting life

One of the first place winning paintings from Erin Wozniak, in the Manifest INPA4 competition/publication. The painting is astonishing enough, but even moreso when you see how small it is.

This guy was young and going places–to Russia at one point to meet with Trotsky, believe it or not, though he was disappointed by what he saw there. By the end of his life, in his Yale lecture, he sounds disenchanted with government as a whole.

“Where any view of Money exists, Art cannot be carried on . . .” –William Blake

I’ve read several stories recently, in Forbes, the Guardian, and at other sites, that question whether or not art is a good investment right now. The implied question is: are we or are we not in a “bubble.” The discussions are built around the highly-publicized prices of the most expensive work sold at the art fairs and in auctions. From my remote perch here in Western New York, where I pay little attention to how creative work gets monetized—except when I try to figure modest prices for what I do—it’s an issue that seems to have little impact on me and most of the artists I consider friends. We all price our work in a range that’s reasonable enough to be safe for anyone who buys the work. It’s a safe expenditure for a couple reasons. First, there isn’t that much room for the price to drop if the market for art somehow were to collapse (as real estate did in 2008). When the bottom fell out of housing prices in 2008, homes in Rochester hardly dropped in value. They hadn’t skyrocketed up in price during the real estate bubble, therefore they were actually valued close to their worth to most families who actually wanted to live in them, not invest in real estate for a quick profit. Second, and more importantly, the people who buy my work, and the work of others I know personally, don’t buy it as an investment, but simply because they want to own it. They know how much labor and talent goes into the work and they see the price as an accurate reflection of both, not as a fleeting marker of an investment’s worth during a continuous boom in value across the art world.

That second point was why I found it so encouraging to have sold seven paintings at my recent Oxford Gallery show. Some were very small, and some were among the largest in the exhibit, so prices had little to do with whether or not people bought the work. The collectors who bought the work—and one in particular who wanted to buy a painting but didn’t—based their purchases on the desire to look at the paintings. (The one who wanted to buy but refrained simply had no more wall space for new work and she had her eye on one of the larger paintings.) You would think these factors would invariably be the case in sales of art, but I suspect that much of the work that sells for millions of dollars now could just as easily go into a vault somewhere as onto someone’s wall. And that money could have been spent just as readily on shares of Apple. I’ve communicated with several of my collectors, and they have said repeatedly how much they love the work they now own, how much what they get from looking at it is worth what they spent on it. For these people, the vagaries of an inflated art market have no relevance at all. I’m sure they don’t want the value of the work to drop—who would? But it isn’t a concern, because they have no plan to ever sell it. What could be better—for me and for them? It’s how the making, selling and ownership of art ought to work, every time.

Bill Santelli called my attention to this great Times story about Leo Bates, an artist whose career, once he went into seclusion, followed a trajectory somewhat like Vivian Maier’s, into obscurity and then out of it, after death. He dropped out of view after a big show at the Albright-Knox, which was itself a remarkable achievement, so he’d been on a path toward more conventional success, and yet gave up on it in favor of success in making the work itself. His devotion to the work, despite everything, is inspiring:

As SoHo boomed, Mr. Bates became more alienated. His working-class roots were at odds with the culture enveloping the scene he once knew.

“The glitz, glitter and boutiques. It became about fashion, money,” said his wife, a librarian who had lived with Mr. Bates in his Grand Street loft throughout the ’70s. “That wasn’t something that Leo…” her voice broke off. “He was a painter,” she said.

And in practical terms, he could not afford to stay. When he lost the lease on the loft, Mr. Bates decided to withdraw. In November 1978, he sold a batch of paintings. Using the proceeds, he made a down payment on 367 Seventh Avenue in Park Slope, moved into the apartment above the storefront and all but vanished.

“That’s the last time he sold anything,” Mrs. Bates said.

He was 34.

In the following years, with the help of his wife’s family, he bought two more walk-ups on the same block in Park Slope, and he became, at least in the eyes of the world, a landlord.

In Manhattan, he soon faded from people’s minds. He didn’t show up at Fanelli’s anymore, Ms. Fish said, and “if you didn’t see the person there, you just lost touch.”

In 1982, Mr. Bates went to a closing party for a show of Mr. Rappaport’s work on Downing Street in the West Village. As Mr. Rappaport recalled, Mr. Bates was upset with him, because Mr. Rappaport had used a small gift from his father to take out an advertising spread in Artforum magazine to promote the show.

“Fairly early in the evening, Leo got up after having a few drinks and he said: ‘Richard is a fool. He just demonstrated how closed the art world is and what a fool I am to even try,’ ” Mr. Rappaport remembered. “And he picked up a serving plate and hurled it at one of my paintings on the wall.” The two never spoke again.

Mr. Bates had a few paintings in group shows in the early ’80s, but from the time he moved to Brooklyn, virtually all that people saw in his hand were the signs he hung outside his buildings: apartment available, inquire inside.

“We didn’t talk to anyone about the art,” Mrs. Bates said.

Mrs. Bates worked in a private library at Bank of America, and they lived on her salary and their income from rentals, which Mr. Bates invested in stocks. But if Mr. Bates had stopped hanging out with painters, he had not stopped painting. In Brooklyn, he painted and drew obsessively. Asked why her husband had stopped selling his work, Mrs. Bates said: “He wanted to keep his body of work together. He wanted to show the progression.”

. . . . Looking at Mr. Bates’s work, it is clear that something happened when he left Manhattan and moved to Brooklyn. When he plunged into deep solitude, he found something new.

There were the muted tones of the Bowery years, the simple triangles, and then suddenly, an explosion of color, mesmerizing patterns.

After the initial burst, the paintings grew more austere. There was more negative space and the colors grew a bit fainter with the years, but the palette remained the same. As did his passion for geometry: Mr. Bates’s last paintings were huge X’s and chevrons that when examined closely revealed tiny grids of dabbed paint.

Mrs. Bates said she did not believe that her husband regretted his decision to work in obscurity. His goal had been not to pander to passing tastes, or to scatter his work to the four winds. He had just painted.

More about this excellent book by Matthew Crawford later, a great follow-up to his first, but couldn’t resist putting this out there, while I’m reading it:

More about this excellent book by Matthew Crawford later, a great follow-up to his first, but couldn’t resist putting this out there, while I’m reading it:

“But consider that when you go deep into some particular skill or art, it trains your powers of concentration and perception. You become more discerning about the objects you are dealing with and, if all goes well, begin to care viscerally about quality, because you have been initiated into an ethic of caring about what you are doing. Usually this happens by the example of some particular person, a mentor, who exemplifies that spirit of craftsmanship. You hear disgust in his voice, or see pleasure on his face, in response to some detail that would be literally invisible to someone not initiated. In this way, judgment develops alongside emotional involvement, unified in what Polanyi calls personal knowledge. Technical training in such a setting, though narrow in its immediate application, may be understood as part of education in the broadest sense: intellectual and moral formation.”

–Matthew Crawford, The World Beyond Your Head

I think he means ethical formation in the sense of ethos, but I own’t argue.

Saville is one of my favorite painters, even though I don’t much enjoy looking at her work. I don’t think I could say this about any other painter. I’m always amazed at how she handles paint, though her subject matter and scale strike me as calculated and contrived. Her choice of grotesque imagery reminds me of Freud and Bacon, dutiful in its lurid depictions of human flesh, with an emphasis on paint for paint’s sake. With all of them, the point seems to be: we’re all just meat. OK, got it. Now what?

In this detail of a nude that appears to be a self-portrait, she’s squatting and exposing her crotch to a camera, having enclosed herself in mirrors that reflect various parts of her body. The way she translates the tones in her face is so masterful and abbreviated and soothingly pleasant–she summarizes areas of color so effectively and, it seems, effortlessly, and in this picture she’s breathing, just waiting to go do something less awkward. She’s thinking, How long do I have to subject myself to this? Those who know Adobe software will recognize qualities in the image that inspire admiration rather than dismissal of the technology, assuming it was involved. If not, all the more impressive. The colors are subtle and beautiful, in and of themselves, and they convey the beauty of her face, even while the full image is as arresting and flagrant as porn, which allows her to situate a lovely face in a painting outre enough to maintain critical respect. It’s a head fake. See what I’ve got? Made you flinch by shoving myself at you. Don’t worry, I won’t use it on you. Whew. It would be great to see her apply this same facility to commonplace things and people, rather than rely on the spectacle of unappealing bodies and body parts to get people to stop and not look away. So, I love this painting, despite itself. You can see it here.

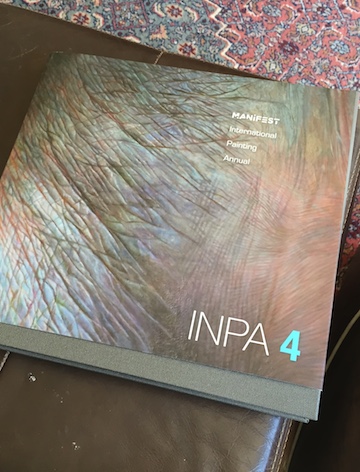

My copies of the Manifest INPA 4 arrived today, and when I saw the three boxes containing them I realized I went overboard while ordering and now own three hardbound and four softbound copies of the International Painting Annual. I’m lucky and honored to have had two paintings picked for inclusion in the book, which may be the finest collection of work I’ve seen in any Manifest publication. There’s a special emphasis on the human figure in this one, and it’s quietly rousing to see bodies and faces, as well  as the human skull I contributed, rendered in so many different ways, filtered through so many different perspectives and sensibilities. It’s a humbling, but consistently thrilling, experience to leaf through the book slowly and take in so much amazing work. The competition picks three winners–an astonishingly talented Erin Wozniak first and foremost with her comparatively tiny, simple and yet utterly alive figurative painting. The rest of us are presented as finalists–a nice way of singling out the three most remarkable artists and yet still offering ample recognition for the 92 others picked for the book, selected from 1560 entries by 563 artists from 32 different countries. This year, I’ve failed to get into the first four shows I’ve entered, which is how it goes some years, so the book arrived as a nice reminder that recognition is a cyclical phenomenon, coming and going on its own schedule, to its own rhythms. I’m going to post quite a few of my favorite paintings from the book over the next few weeks, with some brief comments. It’s great to read, up front, how Manifest is still gathering momentum, expanding its exhibition space and its programs, offering more and more opportunities for solo and group shows, simultaneously. If you want to see what people are doing with paint right now around the world, order a copy from Manifest. It’s well worth the price.

as the human skull I contributed, rendered in so many different ways, filtered through so many different perspectives and sensibilities. It’s a humbling, but consistently thrilling, experience to leaf through the book slowly and take in so much amazing work. The competition picks three winners–an astonishingly talented Erin Wozniak first and foremost with her comparatively tiny, simple and yet utterly alive figurative painting. The rest of us are presented as finalists–a nice way of singling out the three most remarkable artists and yet still offering ample recognition for the 92 others picked for the book, selected from 1560 entries by 563 artists from 32 different countries. This year, I’ve failed to get into the first four shows I’ve entered, which is how it goes some years, so the book arrived as a nice reminder that recognition is a cyclical phenomenon, coming and going on its own schedule, to its own rhythms. I’m going to post quite a few of my favorite paintings from the book over the next few weeks, with some brief comments. It’s great to read, up front, how Manifest is still gathering momentum, expanding its exhibition space and its programs, offering more and more opportunities for solo and group shows, simultaneously. If you want to see what people are doing with paint right now around the world, order a copy from Manifest. It’s well worth the price.

At our recent lunch, Rick Harrington reminded me of David Oleski’s work, and I returned to it, at his website, with pleasure. It’s gotten more subtle and complex in execution, and yet in a way even simpler in its effect, than when I looked a few years ago. It’s a remarkable way to start with Impressionism, especially Monet and Seurat, and somehow also evoke work from a century, as well, finding a home that somehow seems to link Mark Tobey with Morandi. I dread most greens, but he appears to have devoted countless hours to finding new ways to see that color. I like how his areas of color seem to sit quietly and stay where they are, without any sense that one area of paint is moving toward another, no hint of gesture, as if a realistic image of a pear has settled into simpler patterns, all the details disappearing like sediment into a map of peach, green, yellow, and ochre. It’s a mystery how he breaks up what he sees into the cross-hatches he’s trying now. His statement, below, suggests that he contends with something I’ve encountered–that many potential collectors see his work as decorative, since it’s beautiful and devoid of metaphoric content. It’s all perceptual, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t an attempt to give vision a resonance that evokes something like wisdom and joy. It would look great in a room, but that doesn’t mean it’s decor. I like, in his statement, he talks so much about craft and materials.

I came to the realization that many people don’t really understand what MORE

Can’t wait to see this just an hour’s drive away. From ArtVoice:

A few weeks prior to his exhibit entitled The Likeness of Being: Portraits by Philip Burke, which opens on Friday (4/10) at the Burchfield Penney Art Center, Burke met with Artvoice at the office of L.B. Madison Fine Art near his home in Niagara Falls, NY, where much of the work for the upcoming show was being gathered in preparation for display at the gallery.

Moving quickly around a small, sunny room crowded with canvases stacked several deep against the walls, it’s clear that Burke is enthusiastic about his upcoming exhibit—the largest of his career. He points out some early works of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, commissioned for Vanity Fair magazine when it resumed publishing in 1983. The works are smaller—maybe 2 feet by 3 feet—done on cardboard canvasses. “You can see I was poor,” he laughs, “Not that I’m rich now.”

From Manifest, check out the impressive prize this year for what has to be the most exacting art competition anywhere. Time to get to work:

From Manifest, check out the impressive prize this year for what has to be the most exacting art competition anywhere. Time to get to work:

The 6th Annual MANIFEST PRIZE

$5000 award + solo feature exhibit of the winning work

Open to works of any media, any genre/style, any size…

We are very excited to announce that the annual Manifest Prize (ONE) award is increasing to $5,000. This underscores our non-profit organization’s strong desire to reward, showcase, celebrate, and document the most exceptional artwork being made today, and to do this in a non-commercial public context. Further, it is to incentivize the creation of excellent art. Manifest’s mission is centered on championing the importance of quality in visual art. This project is one aspect of the realization of that mission.

The entry process for the 6th annual Manifest Prize award (ONE 6) is now open.

There are no restrictions on submissions to The Manifest Prize. Artists who have been included in previous Manifest projects are always welcome to submit to any future project, including the Manifest Prize.

MEDIA: Open to any and all traditional and non-traditional visual arts media.

Submission deadline: October 1, 2015

For complete info visit: http://www.manifestgallery.org/one

A show of Rick Harrington’s paintings opened a few days ago at the Vilona Gallery in Boulder, Colorado. Rick, and his son Todd, met me at the Gatehouse for lunch last week, followed by an hour-long tour of the Memorial Art Gallery. As a road warrior, Rick is my hero. He has logged many thousands and thousands of miles, tens of thousands probably, driving his work to juried fairs around the country. He works hard and then plays hard, too, fly fishing or whitewater kayaking somewhere within a drive of his shows out West and elsewhere. His painting and his immersion in these recreational ventures into the wild are two sides of one activity for him. Someone clever might be able to make the case that they may simply be one activity viewed from two different points in time. He says the process of exploring and interacting with nature, as a prelude to the painting, immerses him in the world, while en plein air painting makes him more of a static observer. His most ambitious work so far has been a series of large, quasi-abstract landscape paintings attached to windowed boxes full of natural artifacts he has collected from the particular place depicted in the painting. (It reminds me of Burchfield’s quirky, obsessive attempt to depict sounds and other non-visual sensations in his paintings, all in the hope of triggering a deeper identification with nature in the viewer). For the past sixteen years, Rick has relied exclusively on his painting for income. His wife, Darby, is a college administrator and a writer, and her steadier income has balanced the ups and downs of Rick’s. Since 2008, the battle has been tougher, but he’s still making it work.

We talked about the shows I’d seen in New York City, and Todd agreed that Donatello was not only one of the greatest sculptors in history, but also one of our favorite Ninja Turtles. Rick can be hard to hear MORE

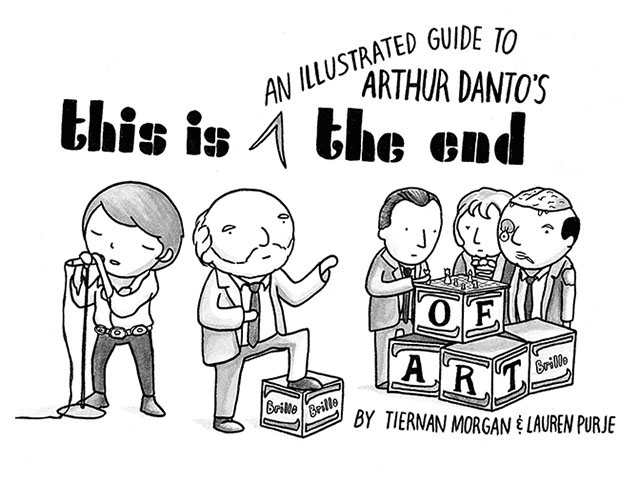

This piece from Hyperallergic is a great, accurate overview of Arthur Danto’s singular contribution to art philosophy. Reading After The End of Art was a liberating and crucial experience for me, though his conclusions at the end of the book were dispiriting. Essentially he asserted that, in the Sixties, art arrived at the end of the long history of its struggle toward greater and greater creative freedom. In that decade, and ever since, it was established that anything could be designated as a work of art, and therefore an artist could literally do anything as a means of expression. Everything was, and is, permitted, to echo Dostoevsky’s phrase, in a different context.

This piece from Hyperallergic is a great, accurate overview of Arthur Danto’s singular contribution to art philosophy. Reading After The End of Art was a liberating and crucial experience for me, though his conclusions at the end of the book were dispiriting. Essentially he asserted that, in the Sixties, art arrived at the end of the long history of its struggle toward greater and greater creative freedom. In that decade, and ever since, it was established that anything could be designated as a work of art, and therefore an artist could literally do anything as a means of expression. Everything was, and is, permitted, to echo Dostoevsky’s phrase, in a different context.

The question then becomes, why create art at all? If the need to push art “forward” toward something historically new is no longer possible, then why make art? Danto’s answer was that each individual has to answer that question, one person at a time, and that the answer to the question is baked into the artwork just as a philosophy of life is embedded in a person’s daily actions. Each individual has to explore and understand why he is creating something, in utter freedom–there is no obligation to do anything in any particular way. The work must justify itself, without relying on an historical context: no more schools of art to advocate one way of doing things over many others. (Danto’s point was that whatever virtues one way of doing things has over another, it isn’t because it’s fresher or more “contemporary” or new in the traditional sense or somehow an historical advance over what has come before.) His key insight was that Pop Art was the art movement to end all art movements, liberating all individual artists to do whatever they wished, and think for themselves, as individuals.

Whether Pop Art holds up now as something that’s still interesting, MORE

On my last, too-short visit to New York City, I was lucky enough to see the astonishing Sculpture in the Age of Donatello at a museum I didn’t know existed until a couple days before my trip: the Museum of Biblical Art, near Columbus Circle. Two works in the show were so powerful that for me they fused together two qualities Edmund Burke tried hard to keep apart: the beautiful and the sublime. For him, beauty was evoked by an art of balance and order, subtlety and color. He called sublime whatever inspired awe or dread or even terror. In his own time, he would have considered Turner an artist of the sublime, with Constable working the field of beauty. Now a couple weeks after finding myself gazing speechless while looking at Donatello’s rendering of Abraham and Isaac, and his almost modernist Prophet, it struck me that the quattrocento sculptor found a way to make beauty indistinguishable from anguish, dread and spiritual abandonment. These two sculptures are humbling visions of two individuals struggling with a sense of complete alienation and loss: not simply loss in the sense of being bereft of everything others enjoy, but a spiritual losing of one’s way. These are two figures who have cut themselves adrift from every mooring, trusting only an inner imperative, even if it leads toward what nearly anyone else would consider madness.

One can think of how this works in the world’s wisdom traditions, MORE

I spent Monday last week mostly wandering around the Metropolitan, re-visiting paintings I’d seen before and seeing a few things I hadn’t, including the murals of Thomas Hart Benton and an exhibit about Native American art, yet the work that made the deepest impression on me was this portrait. I’d seen it on visits before but I really spent some time with it. The quality of his paint is incomparable, and every time I see one of his paintings I understand why he had such a powerful influence over painters as diverse as Manet, Bacon and Fairfield Porter. Yet in this one, it isn’t just beautifully painted; the quality of life is uncanny. From the Metropolitan website:

An Appreciation of the Portrait THEODORE ROUSSEAU Vice-Director, Curator in Chief

The Metropolitan Museum paid an enormous sum to acquire the portrait of Juan de Pareja by Velazquez. The decision to buy the picture was made because it is one of the finest works of art to come on the market in our time. It is among the most beautiful, most living portraits ever painted. Velazquez, whose works are extremely rare, ranks with the greatest painters. This is precisely the kind of object which the Museum has a historic duty to acquire. An unusual thing about this picture is that we know what people thought about it when it was painted. The information comes to us from a Flemish artist, Andreas Schmidt, who was in Rome in 1650 when Velazquez painted it. Schmidt later went to Madrid, where he told the story to Antonio Palomino y Velasco, the historian of Spanish art, who published it some sixty five years later. Palomino tells us that when Velazquez was in Rome, where he had been sent to buy pictures for his master, the king of Spain, he painted the portrait of the pope, Innocent X. In order to practice before beginning his sittings with this supremely important personage, he did a portrait from life of his assistant, the young mulatto painter Juan de Pareja. This was so startling a likeness that when he sent Pareja to show it to some of his friends, it had a sensational effect upon them. They were literally astounded by it, and reacted with a mixture of “admiration and amazement” (the Spanish word asombro implies fright, mixed with surprise and admiration) “not knowing as they looked at the portrait and its model whom to address or where the answer would come from.” The portrait was then shown in an exhibition of outstanding pictures both old and new in the Pantheon, “where it was generally applauded by all the painters from different countries who said about this portrait everything else looked like painting, this alone like reality”.

How many roads you’ve traveled/How many dreams you’ve chased/Across sand and sky and gravel/Looking for one safe place. —Marc Cohn

I spent a couple hours with Matthew Cornell shortly after his opening at Arcadia, talking with him about his work, and it was nearly as rewarding as the hour it allowed me to spend just looking at his exceptionally personal and accomplished paintings. I got there early and had already spent a quarter hour moving from painting to painting, amazed at the way he can evoke unsentimental feeling from images of ordinary, nondescript middle class streets. His work is photo-realistic, but he softens it almost imperceptibly to a dreamlike quality that, for me, hovers between day and night, waking and sleep, memory and immediate sensation. In one painting after another, you feel slightly like a child racing through the dusk from far away, late for dinner, finally catching sight of home. You look at his images and think, “This is America, and this is where I want to be, if I could only get back inside this house.” I’d seen examples of his smaller paintings before at Arcadia, and most of them are modestly scaled, but Pilgrimage, a series of scenes depicting the houses where he and his family lived over the past half century, gathers individual paintings into a larger context that offers a respectful, loving celebration of middle America, haunted by loss but full of quiet, patient vitality. It’s as if he’s nostalgic for a quality of life that has only gone into hiding, biding its time, waiting to re-emerge. Most of the work was already sold, two days after the opening, and that fact—paired with the impeccable quality of the paintings—buoyed me with a sense of hope that simple, direct, and genuine painting, full of love for its subject, without relying on cleverness or pretension, can find a market even in New York City, at prices that reflect the actual value of the work.

Matthew met me at the gallery, only hours before he was to fly back to Florida. He turned out to be tall, good-looking, with a youthful manner for someone who recently turned 50. He was layered up against historic cold temperatures here in the Northeast that must have felt especially bitter after flying to Manhattan with his wife, Rachel, from Orlando, where they live. He told me he undertook this project, in earnest, after both of his parents died a little more than a year ago. We wasted no time and started getting to know one another immediately by talking shop. We began at home plate, as it were: with an oil of the house where he lives with Rachel now, a modest Cape Cod, with a studio in a separate structure at the back of the driveway, and a chain-link fence around the front yard. As with almost all the other paintings, Cornell  captured this home at dusk, late dusk, and the twilight both deepened the color and enabled him to stint effectively on much of the detail that might have been unavoidable in full daylight. Yet the chain link fence looked perfect, as if he had woven it from spider web. The lack of light intensified the beauty of the scene—at noon, it would have faded into a dreary, hard-edged matter-of-factness so typical of photo-realism.

captured this home at dusk, late dusk, and the twilight both deepened the color and enabled him to stint effectively on much of the detail that might have been unavoidable in full daylight. Yet the chain link fence looked perfect, as if he had woven it from spider web. The lack of light intensified the beauty of the scene—at noon, it would have faded into a dreary, hard-edged matter-of-factness so typical of photo-realism.

“That’s our house. We live there. My studio is lit up slightly in the back,” he said.

“The fence is incredible.”

My apologies to McSweeneys for quoting at such length, but I was too busy smiling, and ok, laughing, to rely on my better judgment:

THE RUSSIAN NOVELIST AT HIS DAUGHTER’S 2ND GRADE CLASSROOM’S CAREER DAY

Upon being called on to account for his life, Mr. Leskov, a thin man of about forty-five, rose from the classroom’s dinosaur-themed carpet and, in rising, acknowledged the absurdity of his condition—for all of us, in our own tragic ways, are trapped on a dinosaur carpet of despair, begging to achieve recognition. He silently stood, a pipe at his lips. The children who looked at him were waiting for an answer to a question they would never be able to articulate; the children who didn’t rested their gaze on their classmate, Lucy, who held the lizard her veterinarian father had just shown the class during his presentation.

“What if you told us about a typical day for you?” the teacher asked from a chair in the back. She was a young woman, perhaps thirty, with blonde hair so light it was alabaster and a smile that was plastered over her face, as if to hide the deep pain she felt every second of the day.

“On a typical morning, I wake up, wondering how and why,” he answered. “Light streams in through the gaps in the shades, and I dress in the preposterous costume our society deems appropriate, before entering the kitchen, where my daughter Savannah sits, eating an Eggo waffle from a yellow box . . . . She complains about the type of syrup her mother bought and the amount of butter she used, and in that instant I know that she is the kind of person Father Zossima warned me about on his deathbed, the kind of person who will suck the vitality out of you and cast a gray pallor over all the pleasures of life. Then I curse God for these wicked thoughts and pray to the Almighty Father for forgiveness. This child of mine I must protect, and I must help her understand that it is we who determine our happiness, and we who must decide whether the ridiculous show we designate life is under our control, or whether our attitudes will be controlled by others’ ludicrous values and insane commitments—all of which are ordained by political rulers whose primary technique for gaining approval is bloodlust, and economic rulers who, in the confusion brought on by the insularity that wealth affords, view greed as a spiritual vocation.”

“I… see. Isn’t that interesting, class?” the young woman said. “Everybody pay attention because after the presentations, we’re going to open our coloring notebooks and draw what we heard. Anyone have a question for Mr. Leskov? Yes, Pete?”

The teacher pointed toward Pete, a small, impish boy who would one day no doubt do terrible, unspeakable things to the people he loves.

“How many helicopters have you been in?” Pete asked. MORE

Great thoughts from Fairfield Porter and Langdon Quin on how art offers a path toward particularity of experience, in many ways opposed to what technology is bringing about, from The Painting Center‘s website for an upcoming show that looks exceptional:

A long time resident of both Italy and upstate New York, Langdon Quin presents landscapes in Recent Paintings an exhibition at The Painting Center from March 31–April 25, 2015. The paintings were all created between 2010 and 2015. Each represents a synthesis of visual information derived from plein air oil studies, drawings, photographs, memory and invention. These various sources combine skillfully in the seven Italian landscapes on view here. They reveal Quin’s vision of an exhilarating pictorial world of taut and physically felt spatial tensions mediated by the luminous subtleties of color and light that are particular to each motif.

A decisive moment in Quin’s training as a graduate student at Yale in 1975 occurred on the occasion of a lengthy studio visit by the great painter and art writer Fairfield Porter. This studio visit followed Porter’s seminal public lecture at Yale based on his essay “Technology and Artistic Perception” published in the American Scholar in 1973. In that talk, Porter articulated what he believed to be the “province of painting” in the late 20th century. Quin recalls vividly that Porter likened painting to poetry in urging the consideration of “particularization of experience” as the essential expressive mission of both forms. Porter argued that this particularization stands in opposition to the generalization of experience that technology pushes upon modern culture. Quin’s internalization of Porter’s prescient directive has informed his feelings about picture making ever since. The palpable rapture he feels in front of observable phenomena in nature and the process of its transformation into painting are foremost among the forces that have always guided his artistic efforts.

In addition to Italian Quattrocento influences and French pre-Impressionist models such as Corot and Courbet, Quin has long admired a range of modernist masters as diverse as Bonnard and Balthus, Matisse and Morandi, or the Americans, Louis Eilshemius and Albert York.

Frank Underwood’s favorite game in the new season of House of Cards, with the optical illusions and physically impossible geometry of an Escher. I played it on an LG Pad. Like Portal, the only flaw is that it doesn’t last long enough.

This review of Culture Crash, The Killing of the Creative Class, from the New York Times certainly nails the problem right now for most creative types. One continues to hope, though. The Internet, one way or another, ought to be the solution at some point, connecting creator with audience, as the last paragraph of this book review hints (you’ll have to click on the link to read it.):

From the Times review:

“The most depressing of all is a decimation of cultural institutions that’s been apparent roughly since the turn of the 21st century, but has accelerated in the half-dozen years since the start of the Great Recession. It’s an underreported crisis, he asserts, that has affected not only the higher realms of culture, like classical music and painting, but also indie music and indie film and graphic design. And it’s affected not only the artists and practitioners themselves “but also the many people who supported and spread their work” — music critics and publicists and ushers and record store employees. The injury is bad enough; the notion reflected in the typo-ridden reader comments, that the marketplace rules and that anyone who can’t make it there should quit whining and find a real job, piles on another layer of insult.

Timberg — himself a culture journalist who was a victim of one of The Los Angeles Times’s seemingly endless series of layoffs — makes a good case that, as Bob Dylan once put it, “something there’s been lost.” He starts off with a chapter describing cities and times when everything fell into place: the Boston poetry scene in the ’50s, the Los Angeles art scene of the ’60s, the Austin outlaw-country subculture and the New York punk movement of the ’70s. They all had, he says, a critical mass of creators, which attracted successive infusions of like-minded souls, along with institutions as varied as art galleries, specialized magazines, universities and nightclubs like CBGB or Threadgill’s that spread the vibe, hooked artists up with audiences and, in many cases, provided them with day jobs as they developed their gifts.

That was then, this is now. Numbers tell some of the story. After the financial crisis of 2008, jobs in graphic design fell by 19.8 percent over four years, in photography by 25.6 percent over seven years, and in architecture by 29.8 percent over three years. In 1999, recordings generated $14.6 billion in revenue to the music business; by 2012, the figure was down to $5.35 billion. Of course, owing to the change in the dominant distribution model from physical CDs to (first) downloading MP3 files and (now) streaming on services like Pandora and Spotify, performing artists get a thinner slice of the smaller pie. Timberg puts a human face on the statistics with portraits, scattered throughout the book, of poets, artists, moviemakers and reporters who had been doing good work and making not great but decent livings, when all of a sudden the rug was pulled out from under them.”