Archive Page 15

February 3rd, 2018 by dave dorsey

The comedian and podcast host, Kevin Pollack, says that every good comedian has a bad case of hey-look-at-me-disease. Lesser strains of this malady are common throughout the arts, I think, for better or worse. One thing is certain, social media isn’t the cure.

It’s a truth universally acknowledged that great artists are often self-absorbed. Social media requires us to at least appear to be obsessed with ourselves. But at some point we end up serving this system rather than the other way around—posting everything we do as nourishment for our insatiable “feed.” Being aware of this, I tend to post my latest painting or exhibition with reluctance on Facebook and Instagram, because I think twenty years from now people will look back on this whole phenomenon and think: “How tiresome.” All of this is partly why it took so long for me to write my last post about the recognition I received from Manifest last year–doesn’t this get annoying for some readers?

In a way, the whole social media game is a sweetheart deal for those of us who don’t have mass followings on the Web. It becomes a game of I’ll-like-you-if-you-like-me. (Granted, it isn’t all a mutual schmooze. Most “likes” are sincere.) But social media’s basic OS is reciprocity. You click on other peoples’ like buttons as much as possible to prime the pump for likes in return. Yet isn’t that the definition of an echo chamber? I love coming across an artist now and then for whom I can find no Instagram account. And, ironically, it was refreshing when a now well-known art site that started up a few years ago wrote and asked me to link to their home page, as a way of increasing their rank on Google searches—it was honest and forthright. And I was genuinely impressed with what they were doing. But my attitude is a lot less calculating–I put my work and my thoughts about it out there so that people will discover them if they come looking or else just stumble across it. But hashtags and SEO optimizing search words? It’s never too late to start, I guess. But not today.

January 31st, 2018 by dave dorsey

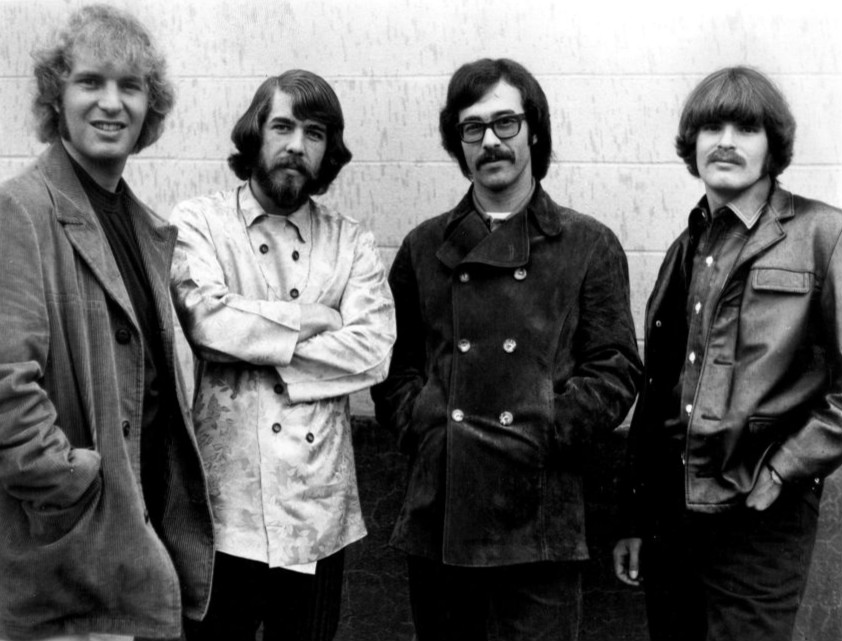

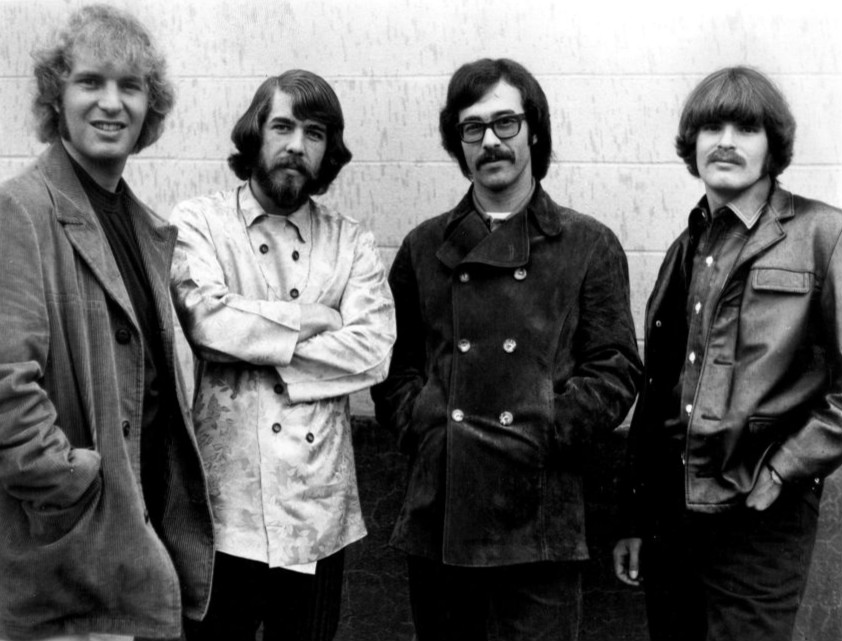

Wayne Williams, left, and Tom Insalaco at their new gallery space circa 1973

At 2 p.m., on Feb. 1, Tom Insalaco and Wayne Williams are going to talk about making art over the past half century in an anniversary event at Finger Lakes Community College. The discussion will be held in the campus gallery named after them. It should be interesting, because they’re both distinctive characters with an independent and occasionally refreshing, iconoclastic view of the art world today. It would be worth attending even if they talked about nothing but the ways in which things have changed for artists since these two began thinking seriously about art more than fifty years ago. The photograph above was taken at their gallery space at 34 S. Main St., in Canandaigua, NY. Barron Naegel will moderate the conversation as part of a larger celebration of the college’s 50th Anniversary. The school opened its first classes on Feb. 1, 1968 as Community College of the Finger Lakes.

Other celebrations of the school’s birthday will include a time capsule to be buried in May and dug up in 2068, and a 124-page commemorative book “This Bold Decision: The Story of Finger Lakes Community College.” The discussion at Williams-Insalaco Gallery 34 will inaugurate an exhibit of work by professors and their students: “Mentors and Mentees: Celebrating 50 Years.”

The show will include work by Insalaco, Williams—both of whom are now retired—as well as work by Rand Darrow, Jeff Feinen, Peter Gerbic, John Lord, Don McWilliams, Bill Santelli, Jean Stephens and Debra Stewart.

Call 585-785-1623 or visit give.flcc.edu for information.

January 26th, 2018 by dave dorsey

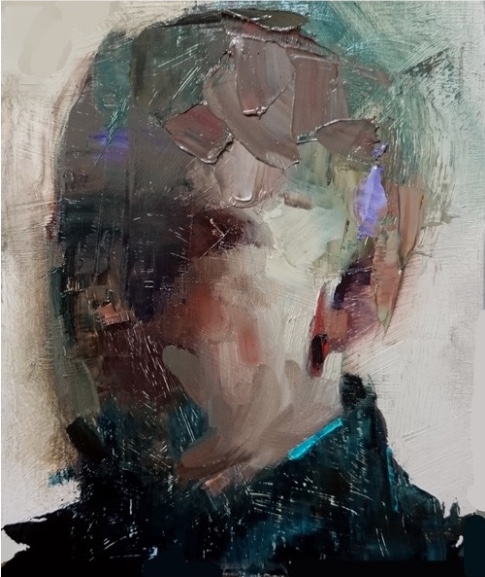

Anamorph, Jason Ferguson

I’m pleased to be able to point to a couple fine honors that Manifest Gallery bestowed on me late last year. I haven’t gotten to posting about this yet in detail because I’ve been immersed in the tunnel of labor required for the paintings I’m going to show in March at Oxford Gallery. Even with marathon painting sessions, the crop of new paintings looks very thin indeed for the sum total of new work since my show in 2015. (A couple non-painting projects stole probably a third of my time in that period, which hopefully is the last time I’ll need to pull myself away from painting to that degree.) But I think my efforts were rewarded well in at least some of these pieces. One of them in particular is the most successful painting I’ve ever done, in terms of exhibition history, awards and now a sale, prior to the show: Breakfast with Golden Raspberries. It’s the reason for one of the honors Manifest sent my way.

First of all, my work was included in Manifest Gallery’s 8th International Painting Annual. For fourteen years, this non-profit in Cincinnati has operated as a hub for artists around the world, enabling them to exhibit without regard for the vagaries of the art market and trends in critical theory about what’s worthy in art. Its jurors are volunteer experts in art and design from across the United States, including professors, working artists, curators, gallery directors, and others qualified and trusted to provide sound objective judgment of the works provided. They cull through a flood of entries for each show and publication the gallery sponsors, winnowing entries down to the fraction it will include—the process is tough, meaning for even very good artists the opportunities are narrow. There’s a wealth of masterful work being done, and too few ways to get it seen and purchased, at least until the Internet eventually lives up to his promise. In the meantime, Manifest serves an almost unique function, and is held in high regard by nearly everyone I know in the art community.

Its 8th annual received 1301 entries, from nearly 400 artists, working in eight countries. The book will include 101 works by 59 of those artists. I haven’t been alerted yet about which of my entries, or which one, was picked.

The second honor was more unusual and represents a new prize offered by the gallery: being selected as a finalist for The Annual Manifest Grand Jury Prize. Jason Ferguson’s Anamorph won the $2,500 prize, a self-portrait of sorts, a 3D printed plastic sculpture derived from CT scans of the artist’s own skull, originally featured in Manifest’s exhibition SCHEMA. My painting was among 40 works by 38 artists chosen as a finalist from a pool of 8,453 separate works submitted for consideration to be included in 20 group and 10 solo exhibitions during the gallery’s 13th season. For this prize, the Manifest organization created a competitive winnowing process to select the best single work out of everything exhibited at the gallery throughout the previous year. Here’s what Manifest announced:

Starting with our 13th season, Manifest has launched a new annual cash award of $2500. The Annual Manifest Grand Jury Prize is a seasonal capstone recognition awarded to one work from among all those exhibited on-site at the gallery across the season. The first Grand Jury Prize is currently considering works exhibited at Manifest from late September 2016 through mid-September 2017.

The jurying process was conducted ‘blind’ without reference to the artist’s personal info, location, or background. Each jury usually consists of at least 5 jurors, and sometimes more than 10. Jury groups are shuffled and changed from exhibit to exhibit, so a pattern does not result. (Learn more about the Manifest jury process here.)

The Manifest Grand Jury Prize will be re-juried by the same advisors who served across the season, excluding any who may have a conflict of interest. When concluded we anticipate that this will result in 20-30 individuals having scored the works shown below in an effort to determine the winner. Learn more about the Manifest Grand Jury Prize here.

At least one work per exhibition is included for consideration. Solo exhibitors are invited to select their preferred work from their exhibition for jury, or may defer to the Director’s choice.

All told, season 13 presented 469 works by 279 artists in 41 states and 10 countries. Details on the exhibitions, and all of season 13, can found at this link. The entire season, and all works shown, will be documented in the forthcoming Manifest Exhibition Annual publication by around spring of 2019.

Thumbnails here may be clicked to see the full image.

January 23rd, 2018 by dave dorsey

I’m listening to Jordan Peterson’s lecture series where he approaches the Old Testament as a psychologist and phenomenologist: he reads the work as Jung would have, as an explication of structures that underlie human nature and the psyche. He speaks for nearly three hours in the first of the series and never gets to the first line of Genesis—his brain is like Kafka’s, bursting with a world that just wants out of his head. Peterson is approaching the whole subject as a rationalist, a scientist trying to understand patterns, examining the text for whatever it conveys with his reason, accepting nothing on faith, without ruling out that there may be much of value in the book that reason can’t plumb.

I’m listening to Jordan Peterson’s lecture series where he approaches the Old Testament as a psychologist and phenomenologist: he reads the work as Jung would have, as an explication of structures that underlie human nature and the psyche. He speaks for nearly three hours in the first of the series and never gets to the first line of Genesis—his brain is like Kafka’s, bursting with a world that just wants out of his head. Peterson is approaching the whole subject as a rationalist, a scientist trying to understand patterns, examining the text for whatever it conveys with his reason, accepting nothing on faith, without ruling out that there may be much of value in the book that reason can’t plumb.

He takes one last question from his audience in the first video, and it has to do with painting. I think the questioner here is suggesting a reproduction of an original painting in some three dimensional form, not a photographic reproduction—some kind of 3D printed version of a work where the paint is duplicated in all its depth. It’s possible to imagine this as an effective way to copy a painting, up to a point. But the surface of even the most organized painting is full of serendipitous chaos, where the substances, the paint and oil, are mixed and applied in the most unpredictable ways, even following the strictest methods. At many levels an artist’s own “copy” of a previous painting wouldn’t be remotely identical to the original, even though the image is mostly the same. I’ve done this myself, painting two versions of a pie tin brimming with blueberries, and they are easily recognized as essentially the same image but are quite visibly different, in multiple ways.

Peterson also talks about historical context, but such an abstract concept seems to veer away from what his friend spoke about: how a painting is an artifact in which the time required to make it becomes evident in the physical features of the painting. Yet historical context for Peterson means the context of human history itself, and he points out how cognitive function follows physical adaptation to the world, grows out of it, not the other way around—in both evolution and in individual perception—and so maybe they are talking about the same thing, in a way. You can feel the time invested in the painting, by the artist—as Peterson says—in the layering of paint. Subconsciously, you sense ways in which the paint betrays to the viewer how much the artist kept going back, or not going back, to certain areas, with new applications of paint, and you feel both the effort and the mastery of the process in an instant, just by looking at the work. All of which makes the work radiate a quality that actually makes time itself visible—as songs so easily make time audible. Not time as in tempo, but the vast sense of past time, as well as the aura of possibility, the depth of the future—and with some concerts, an immersion in nothing but the immediate present.

In the same way, paintings embody the person of the artist in ways that can’t be controlled by the artist—every painting is an involuntary confession of character and personality and the artist’s entire world.

Question: You were in this one room in a museum in New York looking at this one work, a Renaissance masterpiece, and these are generally accepted as amazing artifacts. Does an original work of art, as opposed to a high fidelity reproduction, contain the spirit of the artist who created it and does this account for the disparity in how much you have to pay for it . . .

Peterson: It does in part. I know a good portrait artist. One of the things he pointed out about a great portrait is that it actually contains time. A photograph is one instant. But a portrait is you layered on you layered on you. It has a thickness. It’s a direct manifestation of that creative act of perception. There’s more to it than that. A painting doesn’t end with the frame. We tend to think of a painting as an object but most objects are densely (infused?) with historical context.

Question: If you have a reproduction of a painting that is exactly the same at the level of detail, why would you want the painting?

P: It’s exactly the same at the level of detail but not the level of context.

January 20th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Michael Dorman in Patriot

When I put the last mark on a painting, it’s almost never what I expected it to be during the first brushstroke. And I’m usually surprised several dozen times while getting from start to finish by what I’m required to do. So I can identify a bit with the protagonist in Amazon’s original series, Patriot. It’s a funny, poignant, and whimsically Kafkaesque series built around the personality of a sad-sack folk singer whose day job is working in Special Ops for the CIA. Actually, he has two day jobs. The other is his NOC, his non-official cover, as an industrial engineer working in a bleak Rust Belt factory in Milwaukee where he specializes in the “structural dynamics of flow.” In layman’s terms: piping. His company, McMillan, builds conduits for anything and everything, creating perfect circles in a world of epic imperfection, both planetary and human. These indispensable imperfections are what drive the story forward through one entertaining absurdity after another.

The theme of the show is “the structural dynamics of flow,” the principles of moving anything from Point A to Point B, that could apply to both McMillan piping and counter-intelligence. Likewise, Lakeman, with the help of his family and a co-worker, attempts to get $11 million Euros through airport security into Amsterdam and then on its way to Iran via a courier in Luxembourg. (His family cohort includes Cool Rick, Lakeman’s Beastie Boys-obsessed brother, and his father, who presides over most of the action as a seasoned but compassionate “control” who is professionally imperiled by his son’s mistakes.)

Nothing and no one in the show gets from Point A to Point B as planned. McMillan is going bankrupt. The covert payoff is making the rounds of Luxembourg as more MORE

January 7th, 2018 by dave dorsey

He who would do good to another must do it in Minute Particulars.

General Good is the plea of the scoundrel, hypocrite, and flatterer;

For Art and Science cannot exist but in minutely organized Particulars,

And not in generalizing Demonstrations of the Rational Power . . .

-William Blake

In the passage below, I think Jeff Blehar’s question was getting at something crucial when it comes to any art. It was from a podcast in which three political journalists took off their current affairs hats and spent some time talking about what they really love—music. In particular, Blehar was marveling at the sound of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Green River. He’s really speaking about all the tiny incremental “minute particulars” that go into any band’s unique mature sound. I was struck by his comment because I had a similar thought listening to “Bootleg,” the second song on another of the band’s albums, where, when the bass comes in, suddenly their sound surfaces—an illusion of looseness, the casual way the four instruments seem to lope along, in no great rush to get the job done, and come together as if by accident, two of them riding on the bus just jamming, waiting for the bus to stop and pick up the other two. The way its elements converge make any great work of art unique and individual in a way that’s impossible to duplicate or even describe clearly—and I don’t think it’s something that could be translated into a set of reliable algorithms. In other words you can’t learn how to do it repeatedly—you end up imitating pieces and parts, but not the whole. You can copy a Vermeer, but it won’t be a Vermeer. The jury will be out for a while on whether a computer could create a convincing Vermeer forgery, but I doubt that it ever will. Blehar says:

This is one of the things that gets lost but you hear it in everything they did. It’s that sound. Green River is the best embodiment of the band’s sound. That sound . . . every time they could just walk in and create a song that sounded good, like ear candy, something about the way Fogerty’s guitar, and his brother’s rhythm guitar and the bass and the drums came together on an elemental level is fundamentally satisfying. I guess I’ve never understood why nobody else can reproduce this. Why doesn’t every band try to sound like CCR on Green River? It shouldn’t be hard to do in theory. This is not Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It’s four guys in a room. There isn’t even much over dubbing. But nobody has ever sounded like that. It’s such a remarkable achievement. And it gets neglected because you don’t even notice it. They are so good at it, they draw you away from one of their primary virtues by making it seem so effortless.

What’s distinctive is how minimal CCR kept things, like the earlier Spoon, the simplicity in their production and instrumentation, but I don’t think any of that was a conscious choice. After ten years of work, the band had a perfectly realized style—in Susan Sontag’s sense of MORE

December 23rd, 2017 by dave dorsey

Phil Tippett

A quote posted on the door of the stop motion effects creator for the first Star Wars trilogy, Phil Tippett:

Passion has little to do with euphoria and everything to do with patience. It is not about feeling good. It is about endurance. Like patience, passion comes from the Latin root, pati. It does not mean to flow with exuberance. It means to suffer.

December 20th, 2017 by dave dorsey

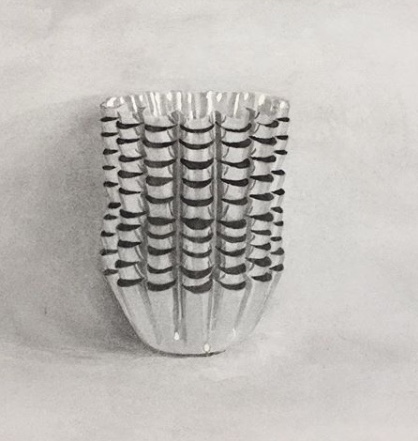

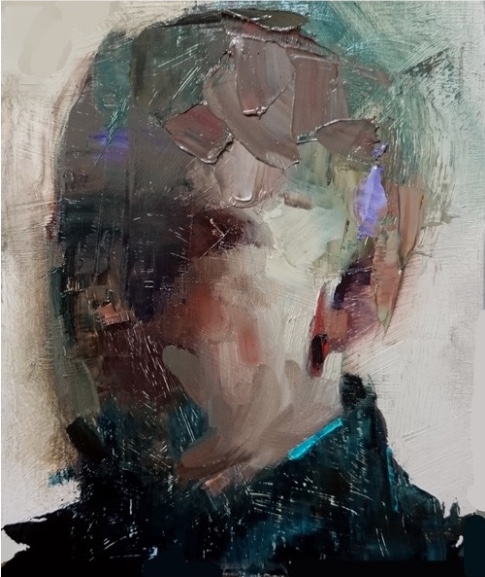

Oven, Benjamin Bjorklund

December 17th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Alma Deutscher

Some people have told me I compose in the musical language of the past and that this is not allowed in the 21st century. In the past it was possible to compose beautiful melodies and beautiful music but today they say I’m not allowed to compose like this because I need to discover the complexity of the modern world. And the point of music is to show the complexity of the world. Well let me tell you a huge secret. I already know the world is complex and can be very ugly, but I think these people have just got a little bit confused. If the world is so ugly, then what’s the point of making it even uglier with ugly music?

— Alma Deutscher, British composer, b. 2005

December 15th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Christopher Isherwood, detail from Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy

Most painters who try to do what a beloved, earlier painter did end up as imitators. Others, like David Hockney, begin where an earlier painter, or set of painters, left off and find a new, idiosyncratic path. Hockney’s a cheerful, sincere post-modernist, borrowing as a tribute to his passion for earlier painters and always using their influence to find himself. They include Matisse, above all, but also Picasso, the Impressionists and post Impressionists, Chardin, Vermeer, Freud, Balthus, and, a recent surprise for me, Piero della Francesca. It isn’t as if this was a secret, since he puts his admiration for the Renaissance painter in plain sight, but I hadn’t paid close enough attention to his work to notice it until now. An afternoon at The Metropolitan Museum of Art a week ago elevated my admiration for Hockney dramatically. Until last Saturday I had no idea how powerful his best early work is, and how wonderfully strange his paintings can seem even when he’s devoted to nothing more than honestly celebrating domesticity, bourgeois happiness and the simple pleasure of human relationships—in other words, the placid order of civilized life.

Having never seen his paintings other than in reproductions, I started paying serious attention to Hockney only around the turn of the century, when I first saw his Polaroids at Retrospektive Photoworks in L.A. during its run there. I immediately loved them, many assembled from dozens of Instagram-square Polaroids. Until then I’d been appreciating him in a sidelong way, fond of his color and the Southern Californian light that transfigured his work when he moved to the U.S. Hockney’s paintings are so intensely illuminated, it makes you realize that Venice Beach is nearly a thousand miles closer to the equator than Venice, Italy and the light of the Midi has nothing on the light that inspired Diebenkorn. To walk out of LAX for the first time into that brilliance must have been like stepping out onto another planet, compared to the Northern glow of Hockney’s native England.

The Metropolitan show highlights the radical simplicity of the earliest famous work that followed Hockney’s migration to the U.S. In each individual painting, MORE

December 7th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy, David Hockney

I got a chance to see the David Hockney retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this past weekend, and was knocked out by seeing, in person, so many paintings I’ve only seen in reproductions until now. A long response to the show will be forthcoming, if I can find the time to finish it. The double portraits–the one above offers a sense of their scale–make the show worth attending.

December 1st, 2017 by dave dorsey

Joshua Huyser, a Minneapolis artist who exhibits internationally, does the simplest possible water colors of single objects, or a small group of identical objects, on a nearly white ground. They’re a delight, and they do what all painting should do: make you look at something as if you’re seeing it for the first time.There’s a guileless quality to the execution that reminds me of Fairfield Porter in that it never lets you forget you’re looking at paint. They’re precise and detailed but not overly so, and color is used very sparingly. Seeing each new painting on Instagram is like hearing a hammer drive a nail just a little more securely into its seat.

November 27th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Cezanne’s studio, courtesy Paris Review/Joel Meyerowitz

Joel Meyerowitz makes some excellent observations about what he noticed when he saw color of the walls in Cezanne’s studio and how that color’s fluid properties, as the background for whatever Cezanne observed in his still life paintings, helped give birth to modernism. Delightful. It’s also wonderful to recognize the little sculpted Cupid still there, so familiar from Cezanne’s painting of it. Here’s an except from the fine little essay, which is actually itself an excerpt from Meyerowitz’s new book, Cezanne’s Objects:

Cézanne painted his studio walls a dark gray with a hint of green. Every object in the studio, illuminated by a vast north window, seemed to be absorbed into the gray of this background. There were no telltale reflections around the edges of the objects to separate them from the background itself, as there would have been had the wall been painted white. Therefore, I could see how Cézanne, making his small, patch-like brush marks, might have moved his gaze from object to background, and back again to the objects, without the familiar intervention of the illusion of space. Cézanne’s was the first voice of “flatness,” the first statement of the modern idea that a painting was simply paint on a flat canvas, nothing more, and the environment he made served this idea. The play of light on this particular tone of gray was a precisely keyed background hum that allowed a new exchange between, say, the red of an apple and the equal value of the gray background. It was a proposal of tonal nearness that welcomed the idea of flatness.

November 24th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Jordan Peterson

Below are excerpts from two recent conversations with Jordan Peterson, a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto. Intellectually, he is following a path laid out by Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell in an attempt to draw psychological truths from the wisdom traditions, otherwise known as major religions (before our culture turned the word “religion” into a political slur and before everything had to be interpreted politically). Peterson moves beyond that in the second conversation, which ought to be of particular interest to artists. I find his thoughts on this subject compelling because I think religious faith draws its vitality from non-conscious wellsprings, just as great art does—faith and creativity both attempt to tap into a larger mind, a larger awareness, than the ego-centric, rational consciousness with its attempt to grip the reins and remain in the saddle of daily experience. For most of my adult life, I would say I’ve been totally in agreement with what Peterson says here, and yet as I get older I worry about an unquestioning embrace of “meaning”. What he says about the fundamental need for meaning is absolutely true, though I think it’s missing an acknowledgement that it ought to be hedged with hesitancy and caution. (Maybe I can venture reluctantly into that in the next post. This subject is pushing me, again, to make sense of why I paint and to question whether or not it adds up, which makes me uncomfortably curious.)

The craving for meaning is fundamental, maybe more fundamental than the instinct to survive itself. It may, at least, be indispensable to that instinct, as Victor Frankl suggested in his account of his time as a prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp, where prisoners who had no framework of meaning died much more readily than those who had a way to make sense of their suffering. I think Donald Kuspit is pointing toward this in much of his published criticism by positing eros, desire, as fundamental in the production of art, and there is definitely an erotic element in nothing more than the energy of oil paint applied to canvas in a certain way. Eros is the affirmation of life over death; so by definition art is erotic. But he means more than that: he means MORE

November 20th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Sometime This Winter, Bill Judkin, 36 x 36, acrylic, dye, plaster compound

The Patricia O’Keefe Gallery at St. John Fisher College is exhibiting Bill Judkins paintings from Nov. 13-Jan. 5. This one’s a beauty.

November 17th, 2017 by dave dorsey

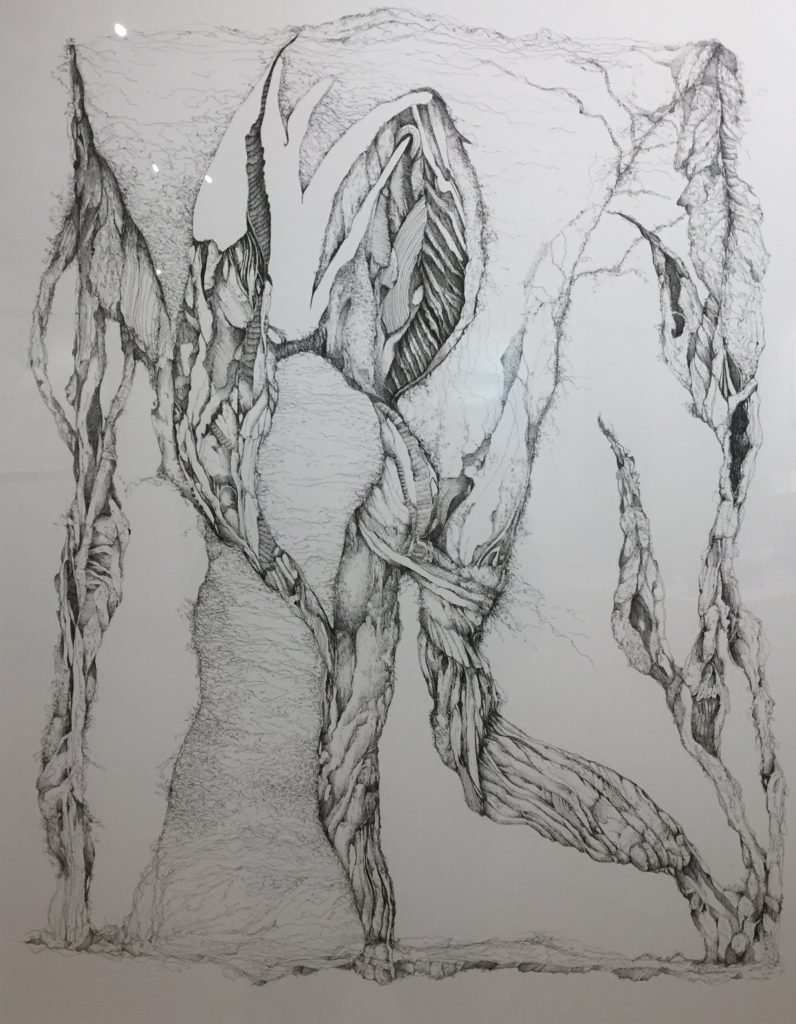

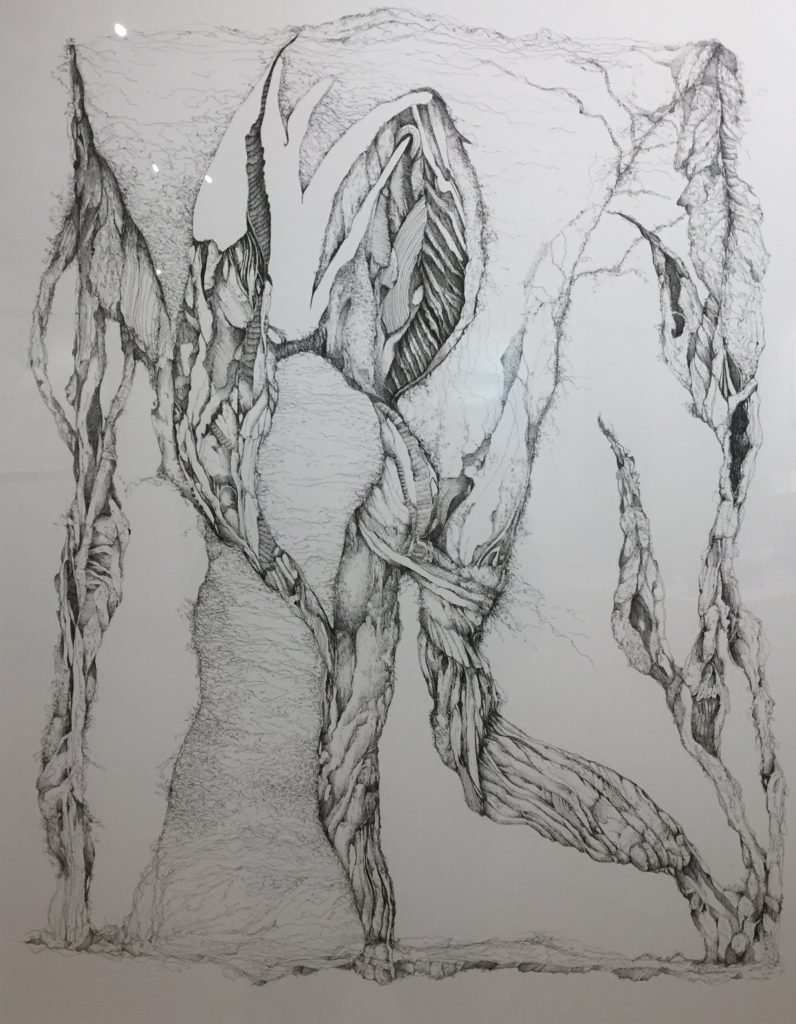

Three Seekers, Bill Stephens, 36 x 28, pen on paper

New drawings from Bill Stephens are on view at the Patricia O’Keefe Ross Gallery at St. John Fisher College. It’s another chance to see some of his work, maybe best described as subliminally generated. Some of his figures and forms seem to be animal, vegetable and mineral all at once. They never just sit there. His colored drawings are getting more and more interesting and one recent one in his Instagram feed is a knockout. Show runs from Nov. 17-Jan. 5.

November 12th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Matriarch

I met with Jean Stephens this week to talk with her about her new exhibition at Oxford Gallery, Continuum. I’d been impressed by her previous solo exhibition at St. John Fisher college, and I wanted to hear her thoughts on how her work has evolved since then. She paints landscapes and artifacts she brings back from her immersions in nature: a deer skull, eggs, nests, and rocks. She and her husband Bill are complementary souls, both spiritually-oriented without being attached to any particular creed or religious practice, though Bill regularly meditates. Both do work that is largely an attempt to tap into the subconscious, in Jean’s case with more emphasis on rendering the outward appearance of the world around her. What struck me in most in the new show—and in examples included in a concurrent exhibit at Main Street Arts—is a series of paintings of eroded rock towers she saw on a trip two years ago to the Southwest. She felt surprisingly at home in the rough-hewn landscape at Arches National Park and that encounter became a catalyst for a new kind of painting. We talked about her work in general and this new series of improvisational geological figures she’s been developing.

I began by asking about two of her paintings in this show that I’d seen in the earlier exhibit in which she takes rocks, sticks, bark and other objects she collects from nature and arranges them in the shape of human figures.

You had these in the St. John Fisher exhibition.

Yes.

You talked before about their spiritual significance to you.

They’re spirit guides. When I started gathering the items to set up the still lifes, the figures just appeared. I started putting things together. That wasn’t my intention. I just let it happen. I feel a spirit comes through me and helps me with the work.

Bill sees his work as well as a spiritual activity as well.

It’s not surprising that things overlap. We’ll start looking like each other eventually.

Where did you collect the objects for these paintings?

Walks in the wood. On the shore of Maine. How many people have boxes of rocks in their studios?

The birch bark is from the bed in our driveway circle.

You collect these things without any idea what you will do with them.

The backgrounds . . . the one with the corn husk and the egg is a piece of wood from an old gun cabinet that a student gave me. This other is part of the bridge support on Route 65. All this wonderful graffiti. Bill and I were taking a walk and I took a photograph of it. I printed it out on a large sheet of drawing paper.

<We moved over to another still life combining a shell with a page of writing superimposed across the surface of the painting, something she’s been doing in other work as well.>

This one is a page from my great grandmother’s autograph book. Her name was Henrietta. These were the sentiments that people wrote in these books. Tender, sweet, sometimes poetic. In those days people had these books. There are little stickers in there. Some of the comments allude to the man she was going to marry. She died young in childbirth. It’s a treasure to have this little part of history.

<We moved to an oil on panel painting of a Robin’s nest with long trailing tendrils, almost jellyfish-style.>

What kind of nest is this?

We had a robin build a nest from a grapevine wreath in our back yard. And when they were done, doves came in and added a couple twigs and used it themselves.

You usually work in oil.

Oil, colored pencils and graphite.

The landscapes are before or after the workshop you did?

After.

Tell me about the workshop.

Timothy Hawkesworth. Irish guy. In Pennsylvania on a farm. Three sisters run the farm. Christmas trees and maple syrup. There’s sheep, chickens. Eastern Pennsylvania. You could go for a two-week commitment, or one week. You get a room to stay in. They feed you three amazing organic meals a day. Tim does a talk every morning. He reads poetry. A lot of it is closing the gap between you and the work. How do you get into the painting? What is your energy approaching the work? Bill and I had just come back from the Southwest. I had two days to do laundry and repack. All those Southwest forms, all that color, all that heat, was still in there, ready to come out. We did the four corners. Moab, Arches, Canyonland, Dead Horse Valley, ended up in Santa Fe and flew out of Albequerque. I had packed a ton of supplies and had no idea what I was going to do (in the workshop). This was two summers ago. I started with drawing, just some gestural line work to get my feet wet. Tim did some demo stuff and came to me one morning and said, “Let me show you something.” I had oils and Liquin and paper and he took something I’d started and just went wild. Whoa. That was starting to crack the door open for me. I’m here, but let’s take some risks. The studio I started in I had a hard time because of all the hay. The sheep were right next to me and I was having trouble breathing. So when there was a change of people it opened up and they moved me to a better space. There was a morning I had a breakdown and a breakthrough. He started by asking the group, “Who was excited when you were born? Who was disappointed when you were born?” I was the third girl in our family and my father was just waiting for that son. So I mean I just spent twenty minutes in tears. He came by with his co-facilitator and asked, “How you doing?” I shared some of my journey. They were amazing. I felt as if I had this big support.

What was he doing by asking that?

It was part of his morning talk. He would talk about work; he mentioned Philip Guston a lot. He likes his work. And I’m not sure how he got to that question. It just hit me. It was what I needed to hear.

It sounds as if he was trying to get you connected to deeper motivations.

Who’s in here? How does that come out? His facilitator said, “We need to bring little Jean out to play. Jean needs to play.” Because I’m pretty tight and controlled.

We’re all dealing with that. I talked about that with Chris. We’re always trying to balance doing what we know how to do while taking chances.

Is that OK? Is that legitimate art?

That drawing that Rembrandt did, the little ink sketch of the mother with child, the baby trying to walk, like a calligrapher he created this figure that is full of energy and it blew Hockney away. I think it’s what you’re talking about.

It’s what we did as kids. What shut that spontaneity down? The what-will-people-think business. It’s OK, Jean.

How far were you into the workshop?

Halfway, at least. It wasn’t until I got into the second week that these started to appear (the towers from Arches park.) These were done there.

They stand out.

The writing was automatic writing.

That’s how it looks.

<She depicts these pillars of sandstone or other rock against lines that appear to be legible writing from a distance, but are simply script-like marks.>

I work with my non-dominant hand, they’re just gestures. It’s informed by the writing from my great grandmother’s book. Being out west, we saw a lot of petroglyphs. The native people out there, this was their form of writing. And we aren’t writing by hand anymore. No penmanship.

No penmanship for me, for sure.

Our sense of history as human beings, writing to each other, is eroding away. (Like the rock towers.)

The line for its own sake, the shape and energy of the line, freed from its need to mean something else. What do you call these?

They spoke to me as figurative, matriarchal. The one on the back wall I call grandmother. They are feminine, powerful. The spirit out there, the native spirit and the land spirit, is very strong.

There’s a tremendous energy in the desert and the mountains.

The earth is exposed in a way that it’s not exposed here. You’re looking at layers of millions of years. Out there, I’m face to face with it. It surprised me because I love the landscape around here.

The west is really different.

How I worked the piece, there’s that sense of erosion, history, the writing again is behind and then across the figure on the lower part. Appearing and disappearing as it wears away. That’s oil on Arches paper used for oil. I pinned a whole bunch of it up on a wall and just went at it with paint.

Just the feel of the paint is so nice. I love the color.

This is the matriarch. The lines are colored pencil. It’s got me a little freaked out because I love doing that, but I also love doing this. I’ve been playing with encaustic now too. It’s different. You work with the hot paint and it does different things. You get texture and surfaces that are unexpected which reminds me of printmaking.

These lines remind me of Gorky. You’re working from the same place as the surrealists and abstract expressionists: the subconscious.

I did the calligraphy first so that’s underneath informing the paint. Some of it gets obscured. Some remains.

That’s cool. There’s a counterpoint between the drawings and the paint. The lines don’t dictate what you’re going to do with the paint.

In the pyramid piece I covered it up.

That’s a more exacting image. The paint in these, though, has the same feel of your hand as the drawing.

I didn’t intend it to be a human figure. But she’s there. She’s in me and needing to come out in this way. I can’t fight it anymore. I’ve been afraid of her too long. I spent two weeks in Hawaii in September. I went with my best friend. The color and the fire; I did a couple watercolors to respond to them. But here probably should be some larger oils maybe on piper.

The encaustic seems like a medium more suited to it. You’re drawn to these elemental things.

I was always outside playing in the fields and the trees as a kid. That’s why I’ve been on this journey in organic form: nests and eggs and landscape.

What is your background in terms of your sense of spirituality?

I think I’m a naturist. The spirit comes through nature, the sky, the stars, the spirit of the land. I was raised Wesleyan Methodist, and it was brutal. I had an opportunity a number of years ago to participate in a vision quest for a fourteen-hour stretch. Spiritual, personal growth, at a retreat center south of Ithaca. One of the final events was this vision quest. We went out when the sun rose and came in when the sun set, no speaking, on your own. We were just asked to notice what was going on in the natural world. I saw a lot of things with wings that day. I saw a hawk just soaring, gliding, and just tipping a wing or its tail, letting go. It was a great metaphor for life.

He was just riding the wind.

That was my message.

November 7th, 2017 by dave dorsey

In conjunction with Oxford Gallery’s show of new work by Chris Baker and Jean Stephens, Continuum, I drove to Weedsport and met with Chris at his home studio for a conversation about his work. Here are some of his comments when he could get a word in edgewise, despite my motor mouth. Chris is super-fit and in September he finished eighth in the world for his classification in Rotterdam’s ITU World Triathlon Grand Final):

Tell me how you got started.

When I was in high school it was for fun. Always enjoyed it. But then when I went to Rochester Institute of Technology for undergraduate work and things started to meld. I wanted to do it, become a professional artist, but realistically . . . you have to have a plan B, or maybe painting is the Plan B. I was lucky enough that I just went for a BFA and when I got out in ‘68 the war was on, and someone said, “If you go into teaching you’re draft-free.” I went into teaching, but it didn’t work. I taught in Auburn for two years. After two years in the service, I got back out, went right to Auburn and got an MFA and again thought I want to paint not teach, but I had to go back into it. In Auburn, they said no openings but there’s an opening in Cato. They hired me when I walked in the door. The superintendent said you’ve got to get your certification. He said “Let me just check, you’ve had two years experience in Auburn” So I got my certification a month later in the mail. Thirty-six years there. That was a great job. Summers off, painted all summer. Over the years I taught kindergarten all the way up to a little bit of college in Auburn.

That’s the great thing about teaching. It really does afford almost enough time to make art.

When we lived in the village we had a carriage house I converted into a studio. I was able to work evenings, weekends, year round.

What sort of work were you doing then?

I started playing around with tempera paints in the classroom.

On the way to gouache.

I went to Commercial Art and said this Crayola tempera, as much as I enjoy it, not sure . . . they said try gouache and that was that.

You were doing representational art even back then?

MORE

November 2nd, 2017 by dave dorsey

Morning Commute, Abby Lammers, oil on canvas, 9 x 12

From abbyblammers, on Instagram. Abby Lammers works here in Rochester and also East Falmouth, MA.

October 29th, 2017 by dave dorsey

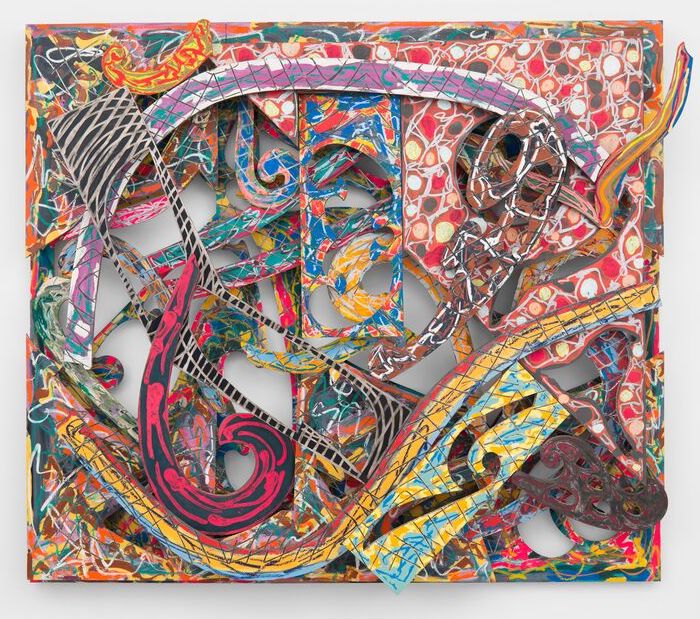

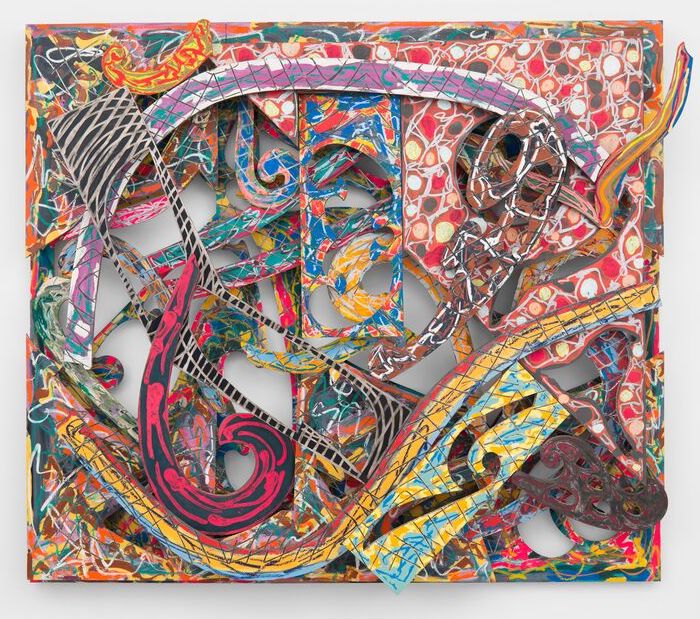

Frank Stella, Mosport 4.75x (1982), © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I couldn’t have put this any better, from the beginning of an essay by Robert Linsley a few years ago on the occasion of a Stella retrospective in Europe. My only quibble is that I’m not sure I see any intellectual side to Stella’s best work (one reason I love it), which Lindsay seems to suggest in a paradoxical way further on, when he talks about feeling the artist behind the work without any conceptual screen between viewer and artist. Art is immediate, even though it can take years coming back to it to actually see and feel a painting directly, and this passage bears that out even though it starts inauspiciously with critic-speak about “voiding of the subjective” while then offering the counterpoint of “feel the artist behind the decisions,” which is what he’s really describing:

I’ve enjoyed Frank Stella’s art since my own beginning as an artist, and the crucial thing has been the enjoyment. The intellectual or theoretical side was always evident—the literalness or factuality, the deliberate voiding of the subjective—and I never needed to take a course or read a tract to feel its necessity or reason, but overriding for me was the pleasure that accompanied the fact that I could also feel the artist behind the decisions. I had a particular affection for the Protractors, although it was many years before I saw one of the original Black Paintings in person, and felt how strongly emotional and romantic they are. I find myself thinking back to those early days in art because recently I’ve acquired a real love for Stella’s Moby Dick series. . . I’ve known about them since they were made, in the late eighties, and always thought they were an important group of works, but only very lately have I really seen them, with a return to feelings about art that perhaps one only has when young. Inspiration means an intake of breath—the breath of life, being whatever one needs and wants to find in art. For me, Picasso, Matisse, Cézanne, and intermittently many others, were truly inspiring—they filled me with a sense of the possibilities of life. Emulation was the necessary beginning, but eventually I had to meet the challenge that was presented, to breath out and keep on breathing. In those days I drank in their work and always had a thirst for more, or, to return to the metaphor of inspiration, the fresh air of art brought every cell to life. Looking at art books was a daily pleasure that gave a perspective on the ordinary dullness of life; visits to museums were transformative. Every contact with art sent me back to the studio. I never had a “disinterested” response to beauty, for me it was always about what could be done—what had been done and what I could do, and every historical achievement was another possible path forward. This practical, achievement oriented attitude is why I like Stella’s writing, which is exactly that way, but I never expected to have such strong feelings about his work. Today I just want to stand beside the Moby Dick reliefs and feel the energy. It’s the unexpectedness of this response that, for me, proves its truth.

I’m listening to

I’m listening to