Archive Page 50

February 9th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Chris and John Pulleyn's human skull

I’m now in possession of a human skull. I don’t own it. Like the skull on my own shoulders, it’s been loaned to me for only a little while. As I expected, it’s a completely unique experience, lifting an actual skull from the cardboard box where it’s been stored for years: to hold what once housed a human being’s eyes and mouth and ears. It didn’t feel as questionable as I thought it might to hold what’s left of someone’s head in my hands—it didn’t seem I was violating some taboo by lifting it up into the light of a pendant lamp in our kitchen. I was delighted to find that it even has a jaw, and most amazing of all, a few teeth. As weathered and aged as it looks, it sort of kept me company. It’s grinning like a Halloween pumpkin, but its look of laughter is friendly, not ghoulish. Actually, it looks kind of happy to be in my house. It sounds odd, but I felt a little less alone with this death’s head sitting on our granite countertop a few feet from the refrigerator.

I wrote earlier about how much an actual human skull costs now—not a model, but the real thing—if you order one on-line, now that the supply from India and China has been choked off by laws in those countries. When I wrote it, I put a link to my post on Facebook and a few hours later got a message from an old friend, Chris Pulleyn: “I know where you can get a skull. And it isn’t buried in my back yard. Call me.” I used to work for Chris and her husband, John, at an ad agency here in Rochester. A few weeks later we met for lunch at Jines, on Park Avenue, spent an hour catching up on the diaspora of ex-employees from their disbanded company. I told them I began my search for a skull after another artist, one of my Brooklyn friends, suggested we collaborate on a series of paintings using skull imagery. The collaboration may not work out, but I’ve gotten interested in doing several paintings, variations on the vanitas tradition, of my own using the skull. So we abandoned our corner booth, left a tip, and then walked out to the parking lot where John fetched the box from the back seat of his car and handed it to me, like contraband. “We didn’t think we should bring it into the restaurant since it says actual human skull on the side,” he said, laughing.

“Does it have the jaw?”

“Oh yes. It’s a good one. You’ll love it,” Chris said. “My father found it on his desk as a joke years ago. When John went into nursing school he sent it to us. You’ll see the note inside the box.”

My initial response to the skull is a sense of pleasure about the color: it’s a rich leathery brown, not white, as if the bone had been steeped in tea. It’s incredibly detailed, and looks like something shaped by hand with loving attention to proportion and line, the size of the apertures for eyes and nose, the curve of the chin, the slope of the brow. The mouth has eroded, so that the sockets where teeth had rooted themselves are a sawtooth row of holes. The eight surviving More

February 6th, 2012 by dave dorsey

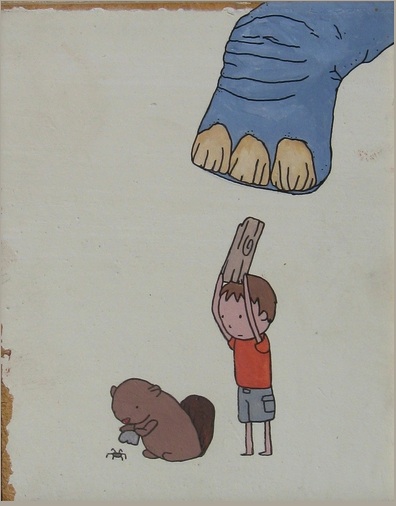

Art for the People: Animal Instinct

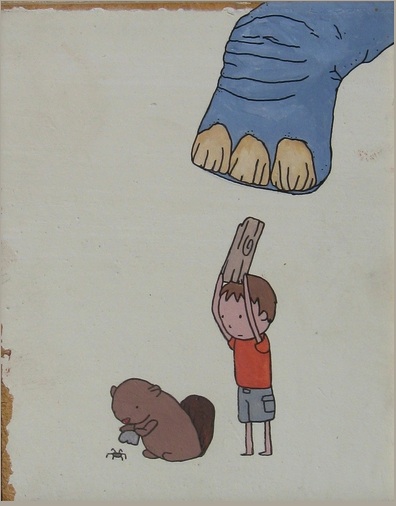

Lauren Purje, a fellow artist at Viridian Artists, just sent me a brief manifesto she’d glued together with scraps of paper a few years ago, announcing her project called Art for the People. It’s from back when she thought she could inspire a small movement where artists saw themselves as servants of their fans, painting things upon request, for almost nothing. To the sound of that, you may ask Lauren, what world do you live in? You will find Lauren roaming somewhere in the vicinity of the land where Lewis Hyde’s gift culture rules. That’s where. Her scanned document looks a bit like a ransom note, as if she were being held hostage by her own ideals—I, Lauren Purje’s superego, will release her into the wild only if you give her an idea for a painting and pay her $50 for whatever she creates, based on it. That’s how I imagine her conscience sounds–resorting to crime to save the world, calling itself her superego, but with its heart in the right place.

What I love about this is project of hers is how it attempts to cut through so much of what has isolated the art world from the vast majority of the population. It’s an attempt to connect with common people who simply want something meaningful to hang on a wall. Jim Ott has taken this even a step further in his itinerant artist project, which I wrote about recently, yet Lauren’s scheme feels to me like something many artists could try in some form or another. (It would be tougher for most of us, though. Not all of us can translate ideas into images the way she does, nor execute work as quickly.) Her one-woman movement goes back to the root of why people do art: to cherish what matters in their lives, as well as offering a way to step back and think about life’s quandaries with a sidelong perspective. That’s Lauren’s speciality, the quizzical irony, the sense of affectionate puzzlement about the most ordinary situations. I can’t go on; I must go on. That sort of thing. It’s what she keeps trying to visualize.

If you want her to paint something for you, keep your idea simple: a phrase, a situation, a moral dilemma, but don’t bother telling her how you want it to look. “In the beginning I said if you even say ‘I want it to be this color’ I will More

February 5th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Still Life with Chocolate Bunny

“You know people talk about films bypassing the intellect and bypassing the thinking part of your brain and behaving in the way that memory does. And the very very best films have that way of . . . they impinge themselves upon your consciousness in a way where you are not entirely sure how (they do it.)”

–Mark Kermode, from his review of The Descendants

When I’m in New York next week, I’m hoping to stop at First Street Gallery to get a look at Erin Raedeke’s paintings. She hasn’t been with the gallery long, and hasn’t been out of school long either, yet her style seems fully realized. She merges a primary interest in color harmonies with the demands of representation and she has a touch that offers just enough detail, and no more, to create a distinct sense of light and form. A representative assortment of her work can be seen at www.erinraedeke.com (it’s lucky to have an uncommon moniker when shopping for uncluttered domain names now). Her village scenes are wonderful, glimpses of quiet small-town streets in a hilly landscape somewhere in the northeast, maybe Pennsylvania, upstate New York, or the Berkshires. Yet this current solo show appears to focus on her still lifes, which offer views of horizontal surfaces covered with either wallpaper or wrapping paper, offering loosely repetitive patterns as a ground for unassuming objects from a child’s playroom or the detritus of a party. These paintings seem steeped in memory, without exactly evoking nostalgia–the soft light that bathes all her pastel colors seems to be aged and faded, shining into view from a previous decade, yet the objects themselves feel fresh and immediate: in one painting, she focuses on one last discarded bite from an Egg McMuffin, or one of its competitive clones. Her objects are quietly festive, or playful, and evocations of childhood seem to be the rule: ribbons, animal crackers, toys, crayon drawings, balloons, ornaments, tinsel, spiral notebooks, Easter candy, plastic Easter eggs, and jelly beans. (I think, given my obsession with them, I’m professionally required to admire anyone who paints jelly beans.)

What’s impressive though, is that she has borrowed and then advanced a technique from Janet Fish in her oversized still lifes, gazing down at objects on a surface, after arranging them in such a way that the pattern of color becomes the driving preoccupation of the work, rather than whatever “meaning” is associated with the objects being used as props. (A vague sense of narrative does keep working to draw together what’s there in the image, but it runs vaguely in the background and isn’t required to “make sense” of anything; her color has a formal coherence all its own.) By using this format from Fish, but cropping the image more severely than Fish did, she moves closer to abstraction. It’s representation which also has the feel of an “all-over” technique, where negative space has been eliminated and there’s really no relief from the field of color and shape she builds, no passages of white that offer a little room to breathe: it’s a brave way of betting on her ability to unify her typically diverse choice of colors. (The image at the top of the post offers more white than usual, which may be why I like it so much.) At times her images get a little busy, and some of her color veers toward tones that feel as if they were sampled from a Sherwin-Williams swatch, but then so did Stella’s, in his early work. Each painting remains an interesting and deeply felt exploration of how to arrange color in such a way that it seems to be applied for its own sake, yet in the end the image offers, as a bonus, a glimpse of the everyday world, as well.

February 1st, 2012 by dave dorsey

I finally got around to watching Objectified on Netflix. It’s a documentary about industrial design, by the makers of Helvetica. Both films are excellent. As I was watching it, I realized that many of us actually live inside an almost entirely pre-imagined world. This is true even if you dwell in the suburbs. A house and lawn are both products of human design. They involve completely natural components, like mice and chickadees and grass and rain, but the grass is cut, and chickadees nest near the bird feeder and mice are sniffing peanut butter in traps and rain gets sluiced off into downspouts. The overall feel of living in a suburban home, or really almost any home, is an experience produced by shaping, tending, adjusting, and adapting to an imagined vision of what daily life should feel like. But for city dwellers, or anyone who lives in some kind of urban environment, you can go through a day and encounter almost nothing that isn’t the product of the human imagination. Spend a day walking through Manhattan and you are living inside a completely imagined world: it was all thought-up by somebody at some point. The roads, the lights, the buildings, the billboards, the vehicles, the hot dog stands, the subway, the signs in the subway, the t-shirts on the people in the subway, the guitar somebody was playing which gets smashed over the musician’s head by somebody who doesn’t like the guy’s acoustic version of Free Bird—everything but the few scarce bits of vegetation poking up through the concrete and the little rectangle of sky overhead. Even the faces and poses of other pedestrians or subway riders are consciously shaped, designed to express indifference and aloofness, usually, if we’re talking about New York. The point is, the world you inhabit was, at some point, an act of imagination. The filmmakers don’t make this point explicitly but I think it was really behind the motivation to make the film: an insight into the fact that we invent a design for our world and then, subliminally and ubiquitously, that design begins to invent us, or at least our experience and behavior. Human design literally structures the world we inhabit. Painting also creates the sense of a world, though it’s one only your imagination can inhabit. Design is an imaginative act, but its ultimate goal is behavioral: it governs how our bodies and minds interact with the physical world all day long. One Japanese designer in the documentary, Naoto Fukasawa, says that he More

January 27th, 2012 by dave dorsey

I got a quick sentimental education this morning from The Very Short List—its headline an homage to Flaubert, in the spirit of the post. It took me to a French website offering a queue of still shots from The Simpsons, alongside the famous paintings that inspired them. It’s a good way to spend a few minutes for the five or six people out there who still might not recognize how much intelligence, wit and imagination goes into that venerable television series. It’s all in French, but the images tell the whole story. The Simpsons is one of popular entertainments most enjoyable ongoing acts of creative theft. It borrows, steals and sends up nearly as much content from other sources as The Wasteland or Girl Talk. The creators of that wonderful cartoon have always layered into the story lines a variety of cultural references that can pass by so quickly, they’re essentially throwaway jokes. The image of Marge sitting at her vanity tending her beehive might have slipped past unrecognized as a parody of Normal Rockwell’s Girl at the Mirror, but most are unmistakable: Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam in the Springfield post office, Homer’s portrait as a version of Van Gogh in his pale blue suit coat, and the Mondrian hanging on the wall of the Simpson living room. Mmmm, painting!

January 26th, 2012 by dave dorsey

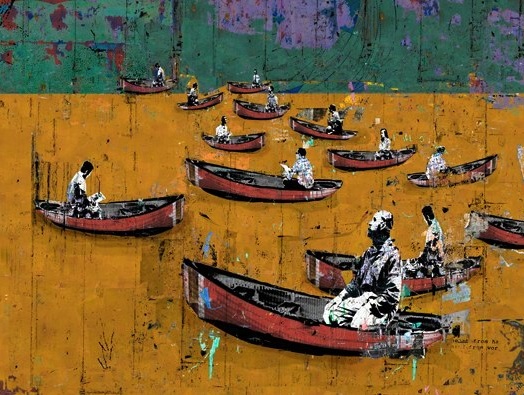

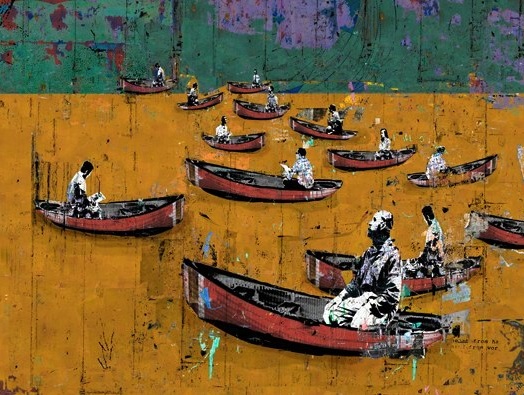

Man in a Boat

In September, the Jung Center in Houston will host a solo show by Daryl Thetford, an artist from Chattanooga, TN, who, over the past six years, has found ways of building original images by layering his own photography into visual mash-ups: the end result often looks a bit like a woodcut or serigraph on the verge of dissolving into a kind of visual white noise. As his starting point, he asks himself a question about contemporary culture and then tries to create a visual correlative of it: a sort of Rorschach blot that works subconsciously on the viewer. He wants the experience of looking at his work to feel a bit like reading tea leaves. He told Architects + Artisans, “It’s amazing what people bring to these. One person will see love and hope, while another says it’s full of pain.” What I love about this approach is that he tries to create an evocative image that has an impact, and conveys a response, that he can’t predict. He works toward formal qualities that have a resonance that isn’t explicitly tied to a particular conceptual meaning. He aims instinctively for the subconscious. He works with software to merge photographs he’s taken of signs, billboards, train cars, sheets of metal, painted walls, old maps, and “other American ephemera that I find on my travels.” From his website:

The colors in all of my photographs originate from my subjects. Numbers and rust often derive from train cars; letters and words come from signs and graffiti, torn paper and pieces of posters are from exterior poster walls. After developing the images from raw digital files, I alter a specific image to black-and- white, and then begins a process of cut and paste that I have developed, using multiple images of close-ups of paint, followed by photographs of signs. Numerous other photos are added and overlapped. Although I have used as few as 10 images to create simple images, often 50 or more photographs are used in this process.

Though his imagery sometimes seems to veer closer to graphic design than fine art, his work evokes rich color harmonies that emerge calmly toward the viewer though all the intentional discord of the surface.

January 23rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

Jane Talcott's Marigolds

I was in New York City for a couple days late last week and attended an opening of a two-person show at the Tai Group on W. 30th St, a consultancy that offers a tremendous, professionally lit space for exhibits. On view, was work by a husband and wife team—Jane Talcott and John Lloyd—whose work occasionally can be hard to tell apart. Lloyd’s city scenes focus on architecture. He paints en plein air and in the four or five days it requires to finish a painting he often learns the history of a building and gets to know the people in the neighborhood. His work is vivid, cheerful, and, as he says, in his artist statement, the act of painting is a way of connecting with the world deeper than simply the conscious activity of moving a brush across a surface:

“Through the relaxed rhythm of the brush strokes I make a connection to the stories happening around me, the slow movements of the clouds, the rhythm of the water, the gestures of the wind moving though the trees, the many varieties of the movements made by the animals and the people around me enjoying their walk..”

He and Talcott work almost entirely in Brooklyn. They met 18 years ago, started painting together 5 years ago, sharing influences and competing in a friendly way, and were married less than two years ago. Their work is heavily gestural, from life, and they both paint urban scenes. Though I liked most of what I saw in the show, Talcott’s still lifes, some of them fairly large, stood out: both daring in their execution and accomplished in their handling of color, which has gotten more intense and varied in the most recent work. One of my favorites was one of the older paintings, a large still life of a melon and a jar, loosely rendered in subtle tones with a limited and cool palette. Another shows a pot of marigolds sitting on a windowsill with what appears to be a cityscape in the distance, possibly one of the bridges connecting Brooklyn to Manhattan. I come away from many shows with an ability to clearly visualize only a few works, but many of Talcott’s compositions remain vivid memories for me, offering a creative tension between spontaneous handling of paint and masterful color choice and composition. Her best work is stylistically indebted to masterful colorists: Matisse, Matthiasdottir, and Freilicher. It’s a show off the usual gallery beat, in a space many small galleries would envy. It’ll go back to see again if I get back to the city before it closes.

January 10th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Work by Sarah F. Burns

So said Solomon, and Sarah F. Burns appears to agree. You can drop in and see a painting by her in progress on her blog. I believe it’s a part of a series of vanitas images she’s doing on commission, not the sort of job one gets hired to do every day. You can read about it on her blog: Sarah F. Burns. She’s also offering a great photograph of a young Francis Bacon holding up two carcasses: Bacon bringing home the bacon, maybe. I’ve gotten behind with these posts, being involved in a writing project this month, and not painting much at all, but I took the time to do a little email with Sarah on the subject of skulls. I’d considered a collaboration with someone on some work based on skull imagery, and it struck me that if I were to do a painting of a skull from life, it would be cheating to use a plastic model, though I couldn’t find any source of actual human skulls on the web. It turns out there are at least one or two, The Bone Room, for example, and the skulls come from China and India, but laws prohibiting their sale have been enacted there so if you’re going to buy one, you’re choosing from the limited and dwindling inventory. So, as it turned out, I found myself debating whether to own the skull of someone who once had a name and had walked around on the planet for a while. It seemed somehow wrong to just buy what remained of this poor fellow’s head, though I don’t know why. He certainly doesn’t need it. It’s costly, too. Looked to me as if $800 was the lowest I could pay. I visualized a box arriving in the mail and slowly opening it to lift the gray dome of bone and hold it in my hand. Why am I still tempted to do this and still feel I’m contemplating something almost immoral, or at least disrespectful. As Sarah put it, it’s “creepy but cool.” Like a vanitas image itself: the whole skull search brought to mind the transience of life, and how little time there really is to get done whatever it is I hope to do, both in this coming year and the following ones. Painting constantly forces you back in touch with your limits on so many fronts: money, skill, physical space in which to work, imagination, and most of all, time.

December 29th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Gorky self-portrait

In a painting, you can’t really hide who you are. Your identity is what someone encounters first, looking at your work, and it’s primarily what you’re offering someone who is beguiled by what you do. I’m not sure most criticism would know what to do with this notion: how do you deconstruct another human being’s mind and heart in its entirely? Does it make sense to ask “What does it mean to be Bill Murray?” Sure, if you are asking, what does it entail, in terms of the divorce, the drinking, the toll of all the brilliant acting, but not if you’re asking that question the way you ask “What does that painting mean?” But if the painting is just the man who made it, in microcosm, then how can it make sense to try to extract something out of the painting apart from what you see in it? You can’t break a person down into her constituent parts and explain her away. (Sure wish I could, sometimes.) A whole human being is really what’s secretly being delivered in any work of creative imagination: music, painting, poetry, or fiction. I tried to think about this here a while back but it came and went, inadequately, and I didn’t give it that much more thought because once you say it, what more is there to say? How do you build some critical theory out of, “Hey, I really like that X. I like spending time with that X.” (The way you “like” a person, which is a pretty unfathomable phenomenon.) But this morning, in replying to an email from a good friend, it leaped back up at me and insisted on getting some attention. I wrote this, though I’ve revised it slightly:

Some peoples’ company you enjoy for a little while and then you move on. Then there are some people who are a part of your life permanently from the moment you meet them. I think art is just like that. The work of some artists never loses its mystery and you keep going back for more for as long as you want and it never gets old. Others have an impact on you for a little while and then you grow out of it and wonder why you were so charmed. I think of art as a corollary to friendship and love between individuals, because that’s really what you’re getting in the art: the person himself or herself, along with their values and experiences and wisdom or lack of it, translated into more lasting terms, into sounds or colors and images or words. When I read Salinger, I’m living with Salinger himself, not just his characters. I have him in the room with me–maybe not the whole person but the best of him, the core of his soul–and he’s keeping me company. He’s there with me, my close friend. In a one-directional way, at least. I don’t need anybody else to introduce me to him or what he “means.” I get it. I love the guy. Quit messing with it. To be saying these things is so far outside the way criticism works now, isn’t it? It seems that way to me. Postmodernism is so intentionally sophisticated about explicating what art does and is—yet most of the time what I love just seems simple and direct in the way it reaches me. It’s all about one human being recognizing another human being in the fullest possible sense in the work, whatever the work is, and wanting to spend time listening to, or watching, that other human being, absorbing the way they apprehend and occupy their world. You want to have them close by, sharing your time with you, reminding you of who you are, if you’re lucky.

What that also means to me is that you are the world you inhabit. So when someone responds to you, they are responding to your world, the angle from which you absorb experience, so that they’re seeing the world you see, and that’s magnified or at least made more visible and explicit through art. It’s more common to say, in relation to a novelist, that something is right out of Kafka’s world or Jane Austen’s world, but it’s just as true of painters, that you are in Avery’s world, or Braque’s, or Turner’s, or Giotto’s. So that being in his or her world, you are spending time with that world’s originator, the one who is present everywhere in it, but nowhere visible.

December 27th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Gorney attending an opening

I spent the morning with AP Gorny last week at a small restaurant in Buffalo. He arrived in the pouring rain on his bicycle. He told me it puts a serious crimp in his ability to get places, but he’s committed to the environment and says he doesn’t want people walking around with oxygen tanks in two generations. Therefore he’s willing to get soaked pedaling around in December. He’s one of those people who looks at every aspect of his life and thinks about the actual outcome of what he does from day to day. We spent two hours together and the conversation wove itself through a variety of different subjects. We almost invariably disagreed and yet I started to find his suppositions thought-provoking and even enlightening.

On the Internet, you’ll have to search hard for any evidence that Gorny actually exists, though a search does yield a few hits, like this one:

Ap Gorny earned an MFA from Yale University. His work is in permanent collections at The Brooklyn Museum, The Victoria and Albert Museum, London; The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Museo de Arte Costarricense, San Jose, Costa Rica; The Philadelphia Museum of Art; The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts; The Franklin Institute; and the National Gallery, Washington, D.C. He is a recipient of major fellowships from The National Endowment for the Arts, Pennsylvania Council for the Arts, and the Pew Fellowships in the Arts.

Not bad for someone who has fled success his entire life. Which is what Gorny maintains he has been doing, both consciously and subconsciously, often by opening his mouth when he probably should have kept it closed. He believes this kind of behavior is instinctive, a path of spiritual survival of sorts. Or, he suggests, maybe what a psychologist would identify as misplaced anger. It’s no accident he isn’t much in evidence in cyberspace. He has tried covering his tracks and values his obscurity, because it’s an element of his entire view that success for an artist is more or less a Devil. That’s a little hyperbolic, intentionally, but not far from the mark.

He’s a reality check for anyone who thinks a painting ought to be an entirely visual form of communication—or that it can be simply a matter of visual sensation. He believes Art is “impurely visual”—more on that in the conversation below. I think of Dave Hickey as a vital critic who has tried to stand apart from 20th century art, to get a clear look at the beast, while calling the entire enterprise into question, yet when I mention his name Gorny dismisses some of Hickey’s views as naïve and wonders why anyone cares what he thinks. “Who cares in the least about a magazine writer? Not a scholar/thinker.” Gorny believes the art world and the “success” it can deliver, often deprives itself and artists of what’s really most essential – the “invisible mental working process of artists reified in their very practice.” So, in most ways, we have little in common in our approach to what art ought to be doing, but More

December 23rd, 2011 by dave dorsey

Roy sculpting his potatoes

This is the look of a man in the grip of an inner necessity. Roy builds a mountain of his potatoes and his children weep because he’s clearly nuts as he says: “This is important . . . ”

He just can’t figure out why. (Welcome to a way of life, Roy.) He doesn’t give up until he gets it right–and even then it takes a random, lucky break for him to simply realize that he’s finished sculpting and recognize what he’s been making. Anyone who has seen Close Encounters knows how his instinctive creative obsession leads to a world of experience he couldn’t have guessed would be waiting for him when he started corrugating the sides of his potatoes with a fork at dinner–and (well it’s a Spielberg movie) an invitation into a large, friendly, hovering vehicle glowing like a Christmas tree.

Happy holidays to anyone who still plays with mashed potatoes or other raw materials.

December 21st, 2011 by dave dorsey

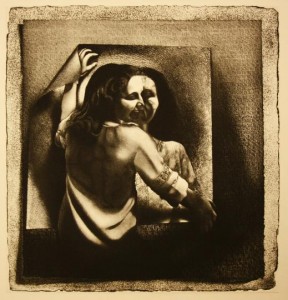

Untitled, AP Gorny

I had breakfast with AP Gorny this morning in Buffalo. His philosophy of art is almost perfectly antithetical to mine, and yet I love talking with someone who can maintain an amiable and perceptive disagreement with me. As William Blake said, “Opposition is true friendship.” He teaches printmaking at Buffalo State University, and he’s a bit of a spark plug when you get him going about the art establishment. I’ll do a post from our talk when I have time to digest it–the conversation ranges far and wide with AP and you realize what he’s giving you is a description of experiences from the perspective outlined in this statement he handed to me, which follows. He’s all about how to be an artist by breaking out of the paradigm of “success” that gets promulgated by nearly everyone in authority. The question of how one manages to keep eating, while righteously pursuing failure, remains a thorny one, I’d say, but I have to admit it’s hard to find fault with what he says here:

From Gorny’s Interdisciplinary Approach to Failure

At this point, in this world I inhabit,

my life is afoot with a program of dismantling

the logic of success/failure.

Artists put themselves

in circumstances purposefully failing,

losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing,

unbecoming, and not knowing.

In other words, offering creative, cooperative,

surprising, unexpected ways of being in the world.

These particular forms of failure

are more attractive to me than

conventional forms of success,

with ambiguous & wide-rainging consequences.

Providing me with a critique of standardized wisdom-production models

disseminated in university settings that just serve to re-inforce cultural

status quo, I daily propose in appropriate (or inappropriate!)

circumstances, that forgetting and losing knowledge (and all those coded

messages of affluence and success) can lead to developing ideas by way of

such a cultural amnesia.

My interdisciplinary approach to failure, obviously leads to problems,

not just in awful academia; it opens a morass negotiating daily life. But I

just say: Like a plumber’s work, it’s a dirty job, but somebody has to do it.

–AP Gorny 11.11.11

December 21st, 2011 by dave dorsey

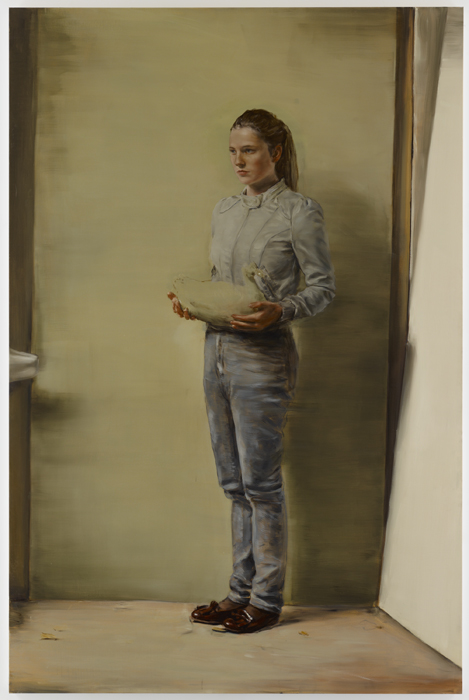

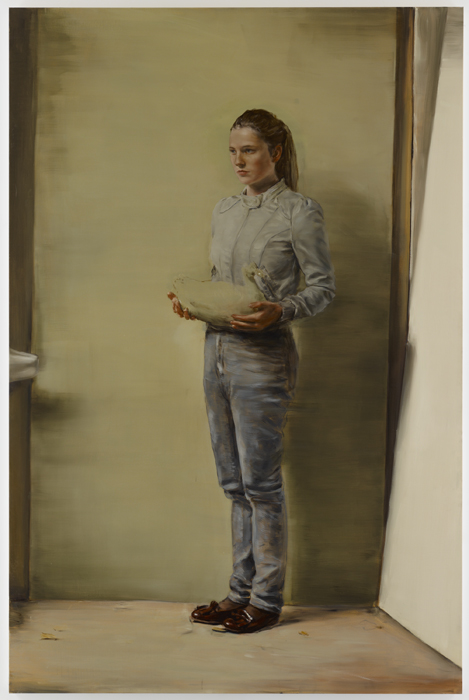

Girl with Duck, Michael Borremans

Last Thursday, two days before the Michael Borremans show closed, just under the wire, more or less, I finally slipped into Zwirner to see it. I was on a quick tour of Chelsea galleries with my young friend from Ohio, Rush Whitaker—who rooms in Brooklyn with Lauren, the subject of my last post, as well as with Krystal Floyd, another young Midwesterner struggling to make it as an artist in New York. When he isn’t painting or writing letters to Taylor Swift, Rush works as a security guard at the Metropolitan Museum. He’s both a writer and an artist and a genuinely warm, totally honest individual who has learned some sort of emotional ju jitsu that turns all the negative energy around him into a fuel for contentment and generosity. He’s also kind of gigantic, at around 240 pounds of genetically bestowed body mass, with some rounded edges from the beer—all of which is to say so he can afford to be indifferent to the slings and arrows of the average day. He has nothing to prove. Still, I’m baffled at how unflappable and cheerful he is, whenever I see him. He’s completely unlike the classic, moody, self-involved egotist an artist is supposed to be. He was astute when it came to the work we looked at—we wandered through more than a dozen galleries, and glanced into many others without going in. We’d just visited David Zwirner’s adjoining gallery where Neo Rausch’s work was on display, and where I was finding Rausch’s images more and more disorienting and nightmarish, the longer I looked at them. Gazing into those scenes, you think there’s something just fundamentally, metaphysically wrong with human experience. Row row row your boat, he says, it won’t matter; life is but a fever dream. Rush couldn’t get enough of those paintings, moving up close, standing back, picking apart the physics of Rausch’s imaginary world and totally getting into it. I just wanted out of there. I wish I’d paid less attention; I would have enjoyed that work more. (The work is fine. I just didn’t want to stay in his world for long. Make of that what you will.)

Walking into the Borremans show . . . man oh man. There’s mastery and then there’s Mastery. Borremans makes it look as if he almost has other things on his mind as he dashes off these figures set in ambiguous, spare rooms, and yet More

December 13th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Michael Winslow on the mic

I’m passing along this video of actor Michael Winslow impersonating the history of the typewriter, which I got recently, as a subscriber to The Very Short List, which sends me a marvelous daily email about imaginative little gems in the vast ocean of the Web. (Sadly, though I get interesting alerts to books, movies and music, the visual arts seem underrepresented there, as they so often are as a subject of interest to your average Web surfer.) Winslow had a role in Police Academy as Larvell “Motor Mouth” Jones. Here he seems somehow to have physically assimilated an entire sequence of typewriters into his body, so that when he creates the sound of someone typing tentatively on one of them, he looks like a man possessed and the effect is beyond uncanny. It’s a little chilling and, eventually, inspiring. At the beginning of the video, Winslow looks as if he’s gathering all his inner ch’i, eyes closed, solar plexus locked into a crunch, to actually imprint words on paper with nothing but the sound emerging from his lips. You find yourself forgetting everything else that ought to be commanding your attention and listening to the magic of keys hitting paper on platen, followed by the incredible scriiiick of the carriage return. It’s a different set of sounds with every single typewriter he imitates. It’s as if he’s been close friends with each one of these machines for half his life. I wonder if most people who click to this video have even heard a typewriter being used, much less an old manual one, except in the movies, but if you have, you’ll agree this little performance is a wonder of mimesis. There’s an element of reverent nostalgia in all this for me, because I miss typewriters, the terrible sense of commitment to each word they entailed with all that heavy impact that could leave a little image of each letter in a sort of braille on the reverse side of the paper. (I mean terrible because who wanted to pick up one of those little eraser wheels with the stiff black bristles on one end and put that to use? Oh, and then came salvation for those of us challenged in the work ethic department, the “correcting Selectric” with the sticky tape that would lift errant words right back off the paper.) Woody Allen has used the same ancient manual typewriter to commit everything he’s ever written to paper, and he gets around the problem of erasers by actually cutting and pasting rectangles of new paper, with new words, over the old ones–as he demonstrated in the recent PBS biography of him. Winslow conveys a lot of that slow, deliberate sense of one-hard-word-after-another in the pace of his imitation, and his imaginary words emerge into the air with the random cadence of corn just starting to pop.

I’m offering this little video because it brought to mind, for me, two things. One was the sensation I got when I first read Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, which I’ve mentioned before here–the way in which he could take the most ordinary details of a routine lunch break and render them fascinating by bringing a new level of microscopic focus and attention to them. It also reminded me of the sensation of looking at an incredibly detailed painting and how it can create a thirst to see more simply by presenting assiduously rendered details, which have no conceptual value or worth, but, because they’ve been brooded upon for hours or days or weeks by an artist, seem to shine with an original kind of interest and value. Recently, Derek Wilkinson’s self-portrait at Manifest, had this effect: it made me marvel at the complexity of color in human skin, seeming to capture the way light reflects off the surface, but also at deeper layers, where the colors deepen and change hue. Representational painting is, in varying degrees, an act of mimesis akin to what Winslow does here, and at its best, it makes you want to return to the world and just look or listen, and be more intensely aware of whatever is simply there. The downside for me in all of this is that now I want to help revive the economy by spending money I don’t have on this.

December 13th, 2011 by dave dorsey

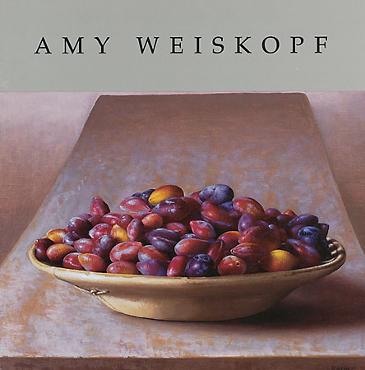

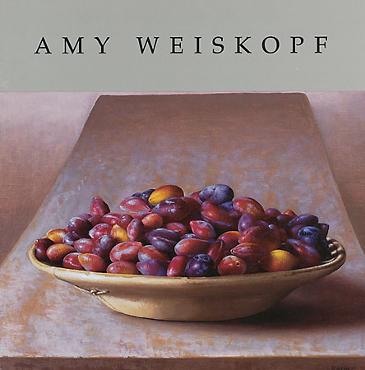

“Today’s art world is wildly eclectic and every artist must make stylistic choices that indicate philosophical positions. I finished school in the early 80’s. At that time art tended to be more conceptual than visual. Sociopolitical issues outweighed aesthetics. Beauty, admittedly difficult to define, was considered elitist, trite, shallow, and inextricably tied to white European men. Pleasure, an equally slippery concept, was not discussed much. My reaction was to move to Italy where I spent the next 9 years looking at what those white European men, and a few women, had done. Call it the aesthetic experience, the pleasure created by a visual image, a nonverbal image, is particular and intense. In a personal and fairly empirical fashion I went looking for that experience, noticed when it happened, and tried to analyze why. For myself, the pleasure in looking is the fundamental force behind the power of visual arts. I believe painting can provide a particularly complex, therefore, pleasurable experience. This complexity is the result of highly orchestrated visual contrasts: spacial, tonal, chromatic and textural. I am a strict formalist; the structure of the painting creates the visual pleasure. I found still life the most suitable genre for organizing these effects. The sheer joy of looking at the painting, that visual and visceral understanding, so difficult to define, should never be eclipsed by more tangible considerations.”

Any Weiskopf, from Painting Perceptions

December 11th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Jim Mott at High Falls gallery

If anyone represents the ideal of what it should mean to be an artist right now, it’s Jim Mott. It may, in fact, be an impossible ideal, but for the past twelve years, Mott has been living an itinerant life, driving around the country with almost no cash, and doing paintings for anyone who offers hospitality. It’s a model of the painting life that takes money almost completely out of the picture. American Artist has written about him, and his last journey, in 2007, from Seattle to Rochester, attracted attention from The Christian Science Monitor and The Today Show. On his trips, he uses cash to pay for nothing but gas. In fact, he convinced a judge in Missoula to take a painting as payment for a speeding ticket. Two prints got him a room in Yellowstone Park. Mostly, though, he arranges to stay at homes and spends enough time there—being fed and kept warm by his hosts—to do a set of small premier coup oil paintings, mostly of nondescript, but nonetheless beautiful, scenes in and around that home. They are done rapidly, intuitively, in the manner of the little sprigs of asparagus that Manet once painted as a gift for a collector who’d bought a larger painting.

Mott’s work reminds me of what Fairfield Porter’s body of work might look like, if he had relied on gray more than he did—in other words, if he’d settled here in the upstate corridor of Buffalo, Rochester and Syracuse, where gray skies are the default backdrop for life. He has the same generalized execution, the same feel for the most mundane moment of the day, the unspectacular and overlooked scene. Mott works small, mostly on little rectangles of conservation board, and he sometimes finishes two paintings a day, and when he succeeds, the image has the kind of life that Hockney celebrated in the book Hand, Eye and Heart, back when he was on his campaign against the use of cameras as a tool for painters. Mott’s work is about creating form through the juxtaposition of values and suggestion, not detail and definition, and it’s as much about the evidence of gesture, the energy embodied in the act of putting paint on a surface—“the scale of these paintings is perfect for the kind of marks I’m making”—as it is about the scene itself. He works in gray and then applies color sparingly—and often with wonderful subtlety—toward the end of the painting session.

“When things work out with a painting, I don’t know how,” he says, “and I never know if I’ll be able to do it again. I’m an anxious painter. I know what’s possible, and I’m never sure how to make it happen. I don’t really like to paint. I like it when the painting’s done. But it can feel worthwhile.”

I met Mott a couple of weeks ago, at lunch and then got together for a look at his current solo show at High Falls gallery, here in Rochester. More

December 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Janet Bohman, Vernita N'Cognita, May Deviney at Viridian

After helping her and a couple other fellow artists hang the new show at Viridian Artists this past weekend, I sat down with Vernita N’Cognita at a little gourmet pizza place around the corner, just off 10th Avenue. She’s been associated with the gallery for more than a decade and is now its director. I consider her the presiding spirit of compassion in that little gallery, someone who has a cool sense of humor and a warm heart. She changed her name from Vernita Nemec to Vernita N’Cognita as an homage to the “unknown artist,” which is consistent with her vocation as director of exhibit space for those who aren’t represented by more commercial galleries. As an artist, she’s built a long-standing reputation in branches of art I know much less about than painting: performance, installations, collage. She was a part of the SoHo scene in the early 70s when it was just emerging, and has been a recognized figure ever since—she’s still being invited to perform in spaces at various sites around the world, though she’s never achieved fame or earned much for her work. She comes from a Catholic family in Ohio, raised by what sounds like a pair of caring, attentive parents, her mother a housewife and her father a tradesman, and this upbringing has been the subject of some of her most interesting and lyrical performances—which are invariably about the way it feels to be a woman in contemporary America. She calls herself a feminist artist, yet when she describes her work, it sounds more subtle and literary than polemical. What I took away from our conversation was a sense, now more than ever, that an artist needs to define the nature of “success” and what it means in a personal way. In most cases, it can’t be about money, nor even about the scope of one’s audience: artistic integrity might ultimately depend on being able to make a living doing something else. And not ordering the tenderloin.

Vernita: When I started out, I lived on 11th. Then on Christopher. Now on Canal St., where I’ve lived for a thousand years. I was mostly painting and doing installations. My first gallery was SOHO20, one of the first feminist galleries. I’m still on their board of directors. Actually, I’m curating a 40-year retrospective for them. After I left SOHO 20, I showed in colleges and other alternative spaces. Then at Gallery 128 on the Lower East Side. Now, in addition to Viridian, I curate a restaurant in Queens. Restaurants make sense except for the fact that the work smells like food. (She laughs) I did a show there and I made my price list like a menu: appetizers, main course and dessert. I ran this arts organization called Artists Talk on Art, which was an historically important organization for ten years. You don’t get money for any of these things, but it broadened my reputation. People think I’m a helper for artists.

As Lauren Purje pointed out, there isn’t just one art world.

People forget that Mary Boone went to RISD and the guy who wears the bathrobe and makes films. . .

Schnabel.

Julian. She went to school with him. So of course he shows in her gallery.

You almost have to define what you mean by success.

Exactly.

Some artists don’t want a gallery to exert control over what they do. You have to figure out how to make money. How have you done it all these years? More

December 6th, 2011 by dave dorsey

It's all about the Woodrows. My iPhone shot of the High Line billboard on 10th

From Jerry Saltz today in New York magazine:

It looks like the art world has entered an ugly finger-pointing period. Call it the Shoot the Wounded Phase: Players at the top are starting to accuse each other of being craven, cronyistic bad actors. Everyone knows something bad is brewing, that some end or explosion is imminent amid the obscene prices, profligate spending, celebrity-artist worship, obnoxious behavior of the rich, and art as entertainment. People are showing up to say, “It wasn’t me. It was him! It was her! It was them!” A few days after Adam Lindemann’s (scathing) column (in the New York Observer) came out, the mega-mogul super-collector Charles Saatchi stepped into the arena, publishing an article in the Guardian. “Being an art buyer these days is comprehensively and indisputably vulgar … the sport of the Eurotrashy, Hedge-fundy, Hamptonites; of trendy oligarchs and oiligarchs; and of art dealers with masturbatory levels of self-regard.” Saatchi goes all out in his attack of the “stupendously rich,” saying they don’t actually “enjoy looking at art” and instead “enjoy having easily recognized, big-brand name pictures, bought ostentatiously in auction rooms at eye-catching prices, to decorate their several homes, floating and otherwise, in an instant demonstration of drop-dead coolth and wealth. Their pleasure is to be found in having their lovely friends measuring the weight of their baubles, and being awestruck.” A much better writer, collector, and thinker than Lindemann, and far more honest, Saatchi gets a lot right about ‘the success of the uber art dealers [being] based upon the mystical power that art now holds over the super-rich.” But he never turns his grand-inquisitor beam on himself, or explains how, somewhere along the line, he went off-track and lost his eye. He himself originated, and has long been the top player in, this terrible business. Good writing aside, it may be that this multimillionaire is a little upset that he’s being displaced by multibillionaires.

December 3rd, 2011 by dave dorsey

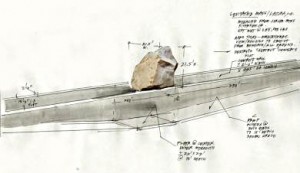

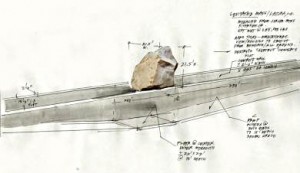

Michael Heizer's rock

Rick Harrington sent some of his fellow painters a column from Mother Jones, about a landscape installation in Los Angeles, suggesting we could hash out, at our next lunch, what the writer, Kevin Drum, is ranting about. The column is a classic reaction to a lot of modern and contemporary art: why is this art? A book could be written about why this question is maybe the only one that matters right now, both to those who think an unhewn rock, an object found in nature, could serve as art, and for those who think it’s a fraud. I think the more interesting question lies in this fellow’s common assumption that one needs an advanced education to appreciate art, which is part of what’s embedded in that query about the nature of art. I don’t think anyone would argue with the fact that you need a bit of study to appreciate art now. When it comes to a lot of what’s emerged over the past century, you need to know how art evolved in the West over the past two thousand years or you can’t fully understand what has happened to art in the 20th and 21st centuries. This isn’t the case with Greek sculpture, or Giotto, or the Sistine Chapel, or Bruegel, or Vermeer . . . you can pick when you think the shift happened, but it’s most likely in the 19th century. My sense, though, is that the more you need a specialized education to appreciate a work of art, the less natural its impact seems to be. It might be a brilliant act of imagination once you grasp the thinking behind it, but should that thinking be required? Does it matter, except in some other realm, such as politics. Is the need for this kind of study a good thing? That doesn’t get raised here, explicitly, but it’s implied. My sense is that, judging from the drawing of this particular rock, I’ll love the way it will look in front of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It’s simple: I like that boulder. But is it art? I don’t really care, except that if the answer is no, I resent that the artist is getting paid more than a landscaper would. And you can count on that: undoubtedly he’ll get a satisfactory percentage of the cost of transporting the rock to L.A. from its origin in Riverside County. The bill will be $10 million, and will be paid by private donors. Is it art? (I imagine Sir Lawrence Olivier asking Dustin Hoffman this question over and over, as a prelude to more dental work in Marathon Man. Slide show rotating with images from Jenny Holzer projected onto the wall of the cell. Is it art? Yes it’s art! Yes yes yes! Oh God, yes! If Duchamp’s urinal is art, so is the boulder! Any oil of cloves left?) The most common reaction to all this is that the project’s absurdity is Sisyphean, except that the rock won’t be rolling back to where it started. And this takes you back to the original question: what is art? It depends on how you define the word. The boulder strikes me, personally, as a Ripley’s Believe It or Not element of landscape design, more than a work of art—though the way I react to a Japanese rock garden would qualify it as a work of art. Is this a stalemate?

If you go back far enough, say around two centuries ago—and at any time prior to that—people didn’t ask themselves whether something was a work of art, but whether or not it was a good one. When I started this blog, and mostly while writing it, I’ve limited myself to talking about painting, though not entirely. I did this partly because I’m a painter and partly as a way of avoiding this question of what qualifies as art. Painting is much easier to define than art as a whole. No one argues that paintings are works of art. The only question is that venerable one: is it any good? The fallback, if you want to be a reactionary and dismiss a lot of what’s happened since the advent of Modernism, would be to say art needs to be, in some degree, visually representational. When what was represented by art began to favor concepts, rather than perceptions, a lot of the interest in looking got lost. (No ideas but in things!) You see a horizon line in Rothko. You can see a flower in Stella’s minimalism. You see a woman in De Kooning. You see a pedestal table in Braque. The leap is bigger in some cases than others. Yet the further you get from visual representation, it seems, the less you want to keep going back for a second or third helping: it just gets less and less interesting, when you lose that tension between what’s happening on the surface and what’s being represented. The bottom line, in all of this, is: how often will I want to look at that rock?

What really irked Drum, in Mother Jones, was the verbiage that served as justification for the rock: “Taken whole, Levitated Mass speaks to the expanse of art history from monolithic stone, to modern forms of abstract geometries and cutting-edge feats of engineering.” The vague all-encompassing hyperbole put him off, understandably, though as art PR goes, it sounds fairly comprehensible, the usual anodyne boilerplate meant to elevate the proceedings: the verbal equivalent of helium. Drum, though, really savages this forgettable little sentence by dissecting it and showing how little it actually conveys. His key point is this: “Installations like this are the kind of thing that’s divorced the art world from the vast majority of modern-day audiences.” There’s the rub. This is the legacy of Modernism: as a consequence of the way Western art has evolved over the past two centuries, art now inhabits a tony intellectual and economic ghetto which seems to get smaller and smaller, the gated community of the most privileged, both in wealth and education. Drum isn’t the only one who finds this intolerable.

December 1st, 2011 by dave dorsey

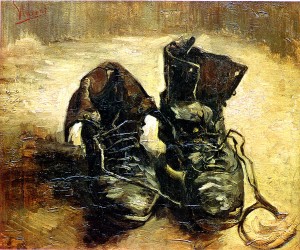

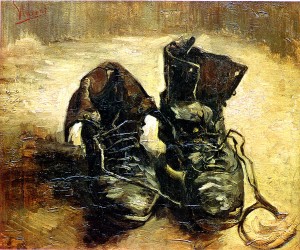

Van Gogh, Pair of Shoes, 1886

Below are several quotes about how art can embody an immediate intuition of the whole of life, and they deserve more attention than appearing in a list here, which is all I can manage at the moment. All three of these writers suggest that visual art can convey far more than it ostensibly is showing you, on its surface. Not metaphorically, but through a purely sensory impression. These three suggest that sensory experience can convey something more encompassing than conceptual knowledge, more subliminal, and more inclusive and unifed—the awareness of the world’s wholeness. Becket tries to explain how this works, in purely psychological terms, and in extremely recondite language, in his essay on Proust. All of these writers suggest something that seems to me alien to much of what’s been implicit in the tradition of Western painting, if not in the practice of it, certainly in the intellectual theorizing that usually runs parallel alongside it. It’s actually closer to traditions of Chinese and Japanese painting.

Harper’s did a funny commentary on the Heidegger quote and how it gave rise to even less comprehensible passages from postmodern theorists, who adopted the German thinker’s practice of inventing their own difficult language to convey their ideas. For example, I’m not sure why he needed “attain to unconcealedness” when “reveal” would seem to do just as well. It would have been so much clearer if he’d simply said: “Looking at the pair of shoes Van Gogh painted, you don’t simply see the objects, but you see the months and years of labor in the fields, the weather of different seasons, the passage of time . . . the entirety of the life built around the protection they offered to a worker’s feet.” In other words, the shoes in Van Gogh’s painting do what landscape paintings more often do: awaken the sense of an entire life, the passing seasons, the passage of time. Something along those lines might have won Heidegger more readers, but mostly he preferred to stick to his oracular pose. These quotes also tangentially remind me of T.S. Eliot’s famous remark about Henry James: “He had a mind so fine no idea could violate it.” It’s always struck me as a quote just as applicable to many of the greatest painters.

Truth happens in Van Gogh’s painting. . . This does not mean that something is correctly represented and rendered here, . . . (it) does not mean that something which is at hand is correctly portrayed, but rather that in the revelation. . . . of the shoes . . . world and earth in their counterplay attain to unconcealedness . . . this shining, joined in the work, is the beautiful. Beauty is one way in which truth essentially occurs in unconcealedness.

—Heidegger, The Origin of the Work of Art

And as soon as I had recognized the taste of the piece of madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-blossom which my aunt used to give me . . . in that moment all the flowers of our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and its surroundings, taking shape and solidarity, sprang into being, town and garden alike, from my cup of tea.

—Proust

The most successful evocative experiment can only project the echo of a past sensation, because, being an act of intellection, it is conditioned by the prejudices of the intelligence which abstracts from any given sensation, . . . whatever word or gesture, sound of perfume, cannot be fitted into the puzzle of a concept. But the essence of any new experience is contained precisely in this mysterious element that a vigilant will rejects as an anachronism . . . no amount of voluntary manipulation can reconstitute in its integrity an impression that the will has—so to speak—buckled into incoherence. But if, by accident, . . . . the central impression of a past sensation recurs as an immediate stimulus which can be instinctively identified by the subject . . .then the total past sensation, not its echo or copy, but the sensation itself, . . . . comes in a rush to engulf the subject in all of the beauty of its infallible proportion.

The most trivial experience . . . is encrusted with elements that logically are not related to it and have consequently been rejected by our intelligence . . . (therefore) Proust does not deal in concepts, he pursues . . . the concrete. He admires the frescoes of the Paduan Arena because their symbolism is handled as a reality, special, literal and concrete, and is not merely the pictorial transmission of a notion.

Lying in bed at dawn, the exact quality of the weather, temperature and visibility, is transmitted to him in terms of sound, in the chimes and the calls of the hawkers.

—Samuel Beckett