Archive Page 14

April 14th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Spiral Bowl with Flat Screen, oil on linen, 16” x 24”

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 12th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Snowcapped, oil on linen, 10” x 16”

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 11th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Not bad, huh? I wouldn’t mind seeing a shot of the photographer as he snapped this one. Free of Instagram filters, too! Jason Kottke on Instagram: “This is an aerial photograph of Edinburgh taken by Alfred Buckham circa 1920. He stood in the open cockpit of a plane while working, one leg tied to the seat for safety.” Full story on kottke.org.

Not bad, huh? I wouldn’t mind seeing a shot of the photographer as he snapped this one. Free of Instagram filters, too! Jason Kottke on Instagram: “This is an aerial photograph of Edinburgh taken by Alfred Buckham circa 1920. He stood in the open cockpit of a plane while working, one leg tied to the seat for safety.” Full story on kottke.org.

April 10th, 2018 by dave dorsey

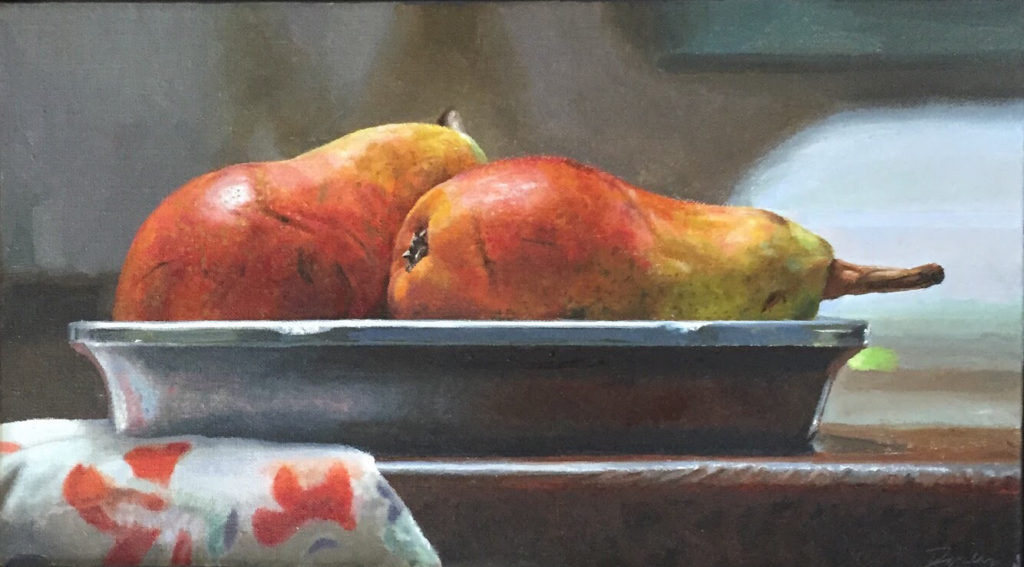

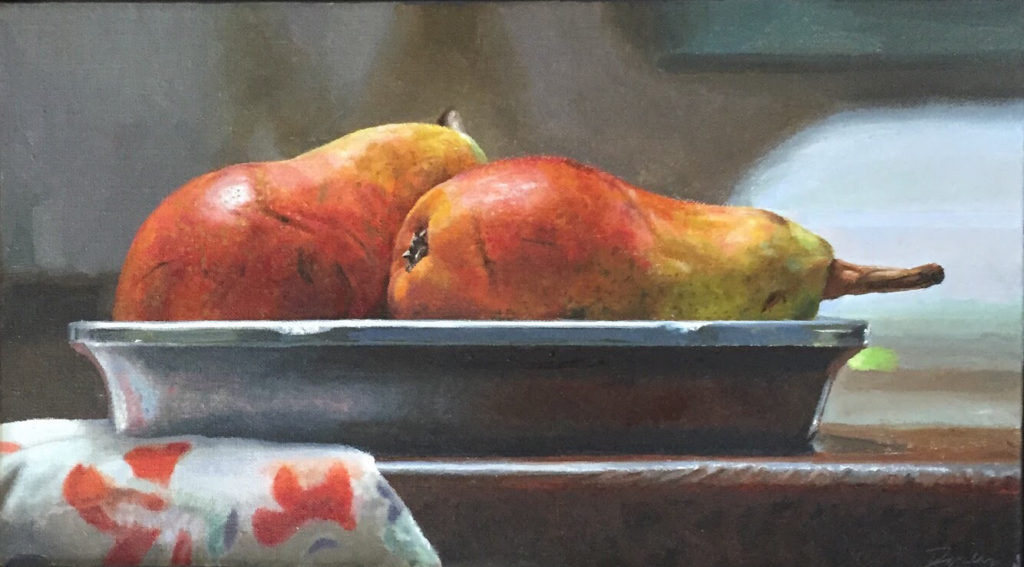

Red Bartletts, oil on linen, 10″ x 18″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 8th, 2018 by dave dorsey

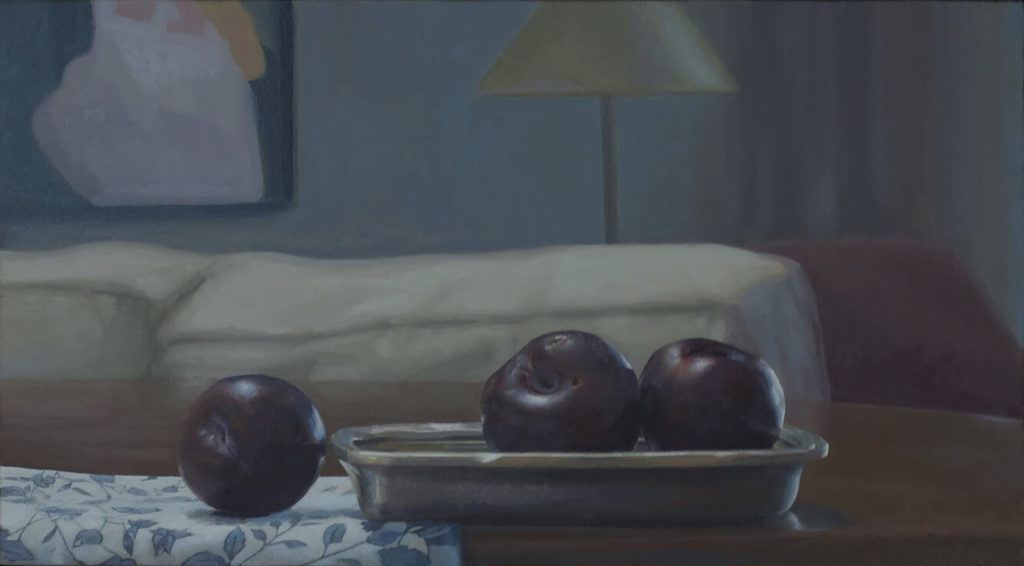

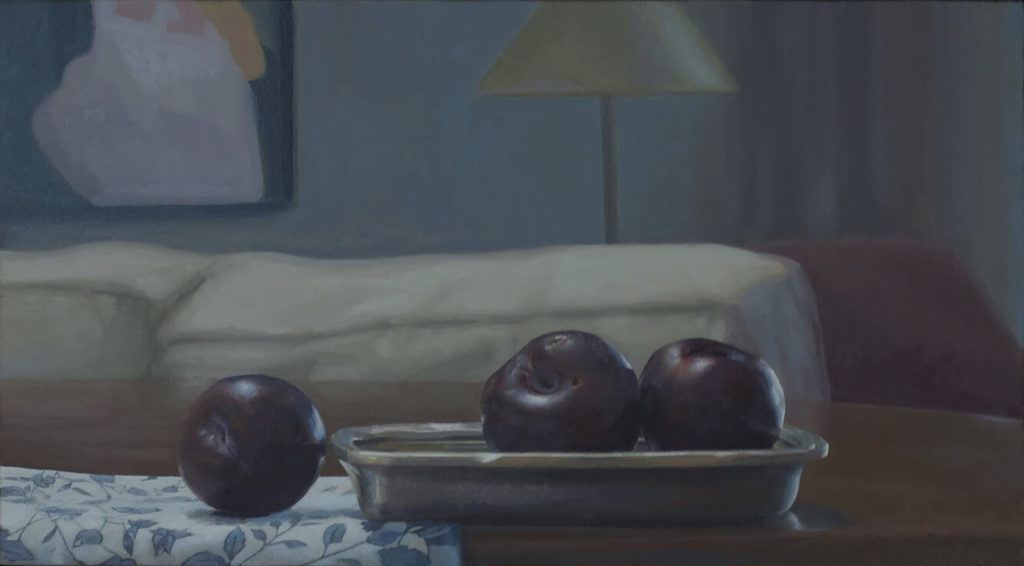

Plums with Milton Avery, oil on linen, 20” x 36”

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 6th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Patterns, oil on linen, 10″ x 16″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 4th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Light North and South, oil on linen, 12” x 20”

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

April 2nd, 2018 by dave dorsey

Kiwi in Bottle Stand, oil on linen, 20” x 36”

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

March 30th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Everything Is Illuminated, oil on linen, 18″ x 20″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

March 29th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Nightfall Study, Karl Heerdt, oil on linen panel

When I called Karl Heerdt last week he’d been out in his garage working on some sheet metal for the ’65 Mustang fastback he’s been restoring. I had no idea he did this, and to hear him talk about it filled me with instant envy. He loves simply getting under a hood and replacing pistons and rocker arms and carburetors. Yet he also doesn’t mind reselling what amounts to a completely new classic American car he’s put together with a little help from his friends. He did this recently with a Shelby Cobra replica, which is about to make its way back into his garage for a few more tweaks before his buyer takes delivery.

“Oh you bastard,” I said, but I’m not sure he heard me, because he was laughing at the fact that he was glad to come inside to answer the phone and get warm again. An upstate New York March can be as cruel as April, both here in Pittsford and down the turnpike in Tonawanda as well. “I’d love to have the tools to tear down an old 70s car and rebuild it. You’re living my dream.”

“It doesn’t take all that many special tools,” he said. “We got sheet metal replaced, hood and doors and things. It’s way more work than I expected. We completely tore it apart and did a complete rebuild on the engine and transmission and drive train. So everything is new. We updated the suspension, and we lowered it.”

You can get a glimpse of the car on his Instagram feed, still a dull matte gray from the primer coat. It’s one of the earliest Mustangs, a few years before the rumbling Highland Green menace Steve McQueen made famous in Bullitt. It takes us a while to get around to talking about his painting, because I go off on a tangent about how Dave Hickey wrote an essay in which he extolled car customization as a form of three-dimensional art. I couldn’t agree more, partly on philosophical grounds but also because it would give me an excuse to spend a year in my own garage learning how to take a small block V-8 apart and put it back together in a way that wouldn’t turn it into a massive paper weight.

Heerdt is my co-exhibitor at Oxford Gallery right now, in a show entitled Hushed Reverberations (Jim Hall borrowed it from a Santayana quote), MORE

March 26th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Eros, oil on linen, 12 x 16

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

March 25th, 2018 by dave dorsey

(Photo by: Ron Batzdorff/NBC)

Kristen Bell, recently deceased: So, who was right?

Ted Danson, afterlife engineer: Right?

About the afterlife?

Oh well, Hindus. They were about 5 percent right. Jews, Christians, Buddhists, all were about 5 percent right. Everybody was about 5 percent right, except for Doug Forcett.

Who’s Doug Forcett?

Doug was a stoner kid who lived in Calgary in the 1970s. One night he got really high on mushrooms and his best friend Randy said hey what do you think happens when you die and Doug launched into this long monologue where he got right 92 percent correct. We couldn’t believe what we were hearing. That’s him up there matter of fact. He’s pretty famous around here.

<He has his goofy portrait on the wall.>

Generally speaking there’s a good place and a bad place. You’re in the good place. You’re OK Eleanor.

Who’s in the bad place?

Every U.S. president ever except Lincoln. Mozart, Picasso, Elvis, basically every artist ever.

March 24th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Begonias and Dahlias, oil on linen, 26″ x 52″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

March 22nd, 2018 by dave dorsey

Breakfast with Golden Raspberries, oil on linen, 30″ x 46″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

March 20th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Bowl with Stovetop, oil on linen, 12″ x 18″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

March 18th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Blues, Browns, and Gray, oil on linen, 10″ x 16″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

March 16th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Begonias and Dahlias, 26” x 52”, oil on linen.

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

March 15th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Belle and Blue Bottle, oil on panel, 18″ x 18″

From Hushed Reverberations, my two-person exhibition with Karl Heerdt at Oxford Gallery, Rochester, NY, from March 17 through April 21. Reception from 5:30 to 7:30 on March 24.

February 28th, 2018 by dave dorsey

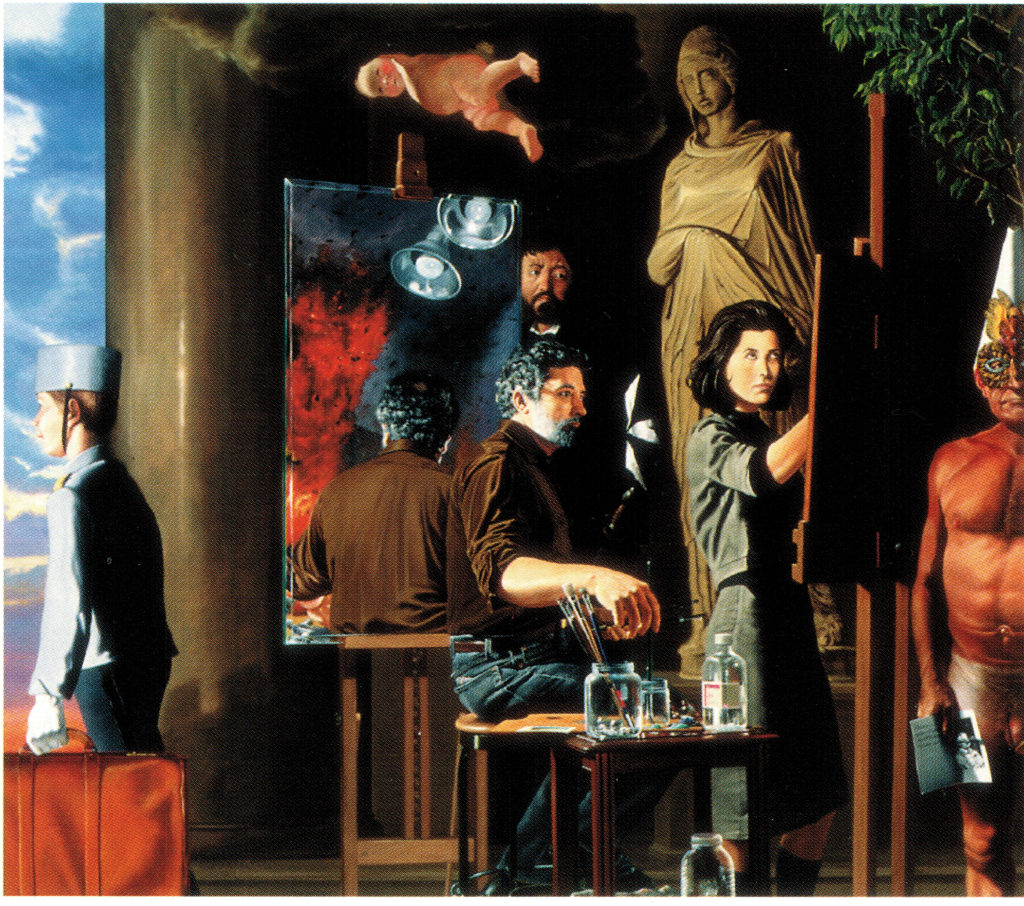

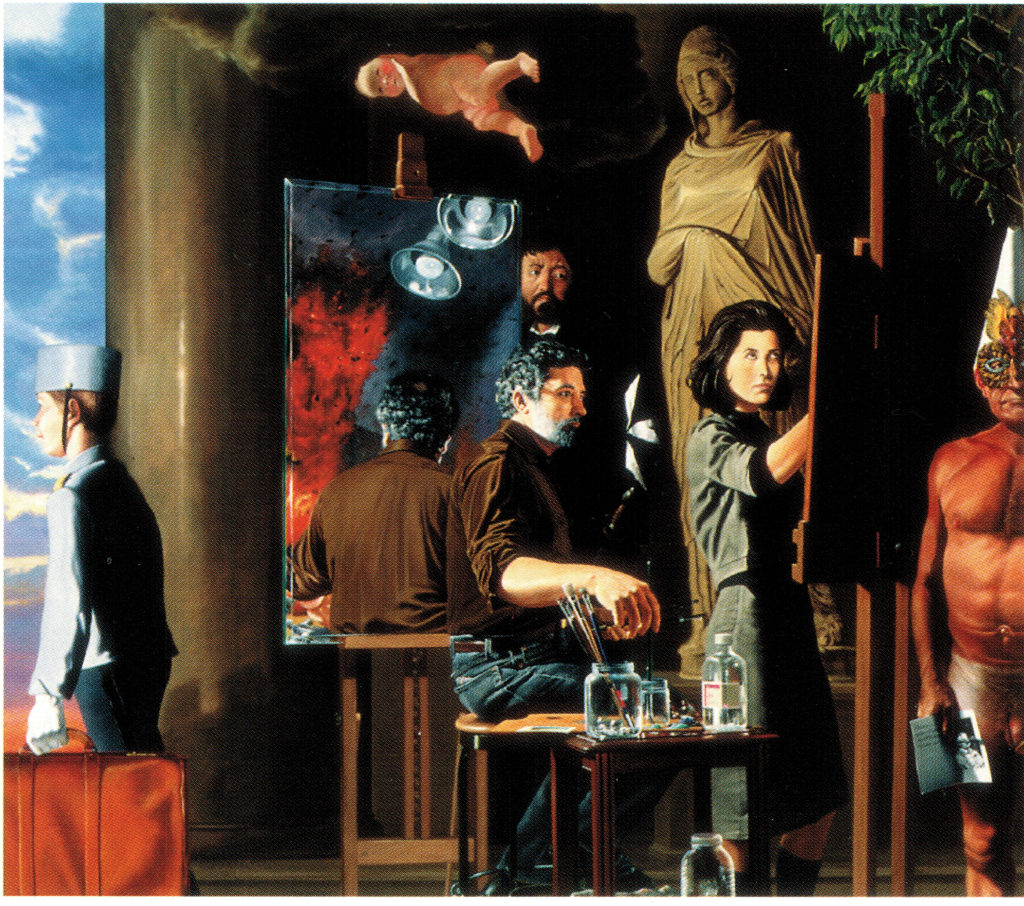

Tribute #2, Tom Insalaco

Tom Insalaco is a bit of a phantom. After six decades of making art, this award-winning painter continues to create new art every day, but he makes little additional effort to prove that he exists. In a world where social media has become the latest addictive drug and the new hothouse for growing a career, he shuns publicity and refuses to promote himself. A Google search turns up almost nothing about him, except for the samples of his work at Oxford Gallery’s website. He has no website of his own. He has a Gmail address, but insists that he doesn’t know how to use it. At midnight, sometimes, he steals onto the Internet but leaves everything as he found it. He watches art documentaries on YouTube or Netflix, or clicks around to discover another contemporary painter to admire or to see what’s happening at his favorite Manhattan galleries, but he signs off without leaving a public trail. Though he’s as prolific as ever, the Internet has yet to recognize his existence—which means almost no one has access to his five decades of work.[1]

At the age of 75, he rarely enters exhibitions though for decades he has been repeatedly invited into the Memorial Art Gallery’s biennial Rochester/Finger Lakes Exhibition, widely considered the most prestigious show for visual artists throughout New York State west of the Catskills. More often than not, he wins one of the exhibition’s awards. Not long ago, he contacted that museum and asked how many times he had been included in the Finger Lakes show. (He doesn’t keep count of his honors.) He was put on hold for a bit, and the woman returned with a note of surprise in her voice, telling him that he was the single most exhibited artist in the exhibition’s history. His first inclusion was back when he was in graduate school at Rochester Institute of Technology in 1969. Since that phone call, he hasn’t heard from anyone at MAG suggesting maybe it’s time to offer the public a long-overdue Insalaco retrospective. He remains mostly under the radar because he’s too busy making art to worry about whether or not anyone sees it.

His exhibitions have been few and far between, but they have been distinguished. He achieved modest regional fame throughout the state after he completed his monumental Tribute Triptych in the early 90s in reaction to the random murder of his brother. A show was initially organized around it by Finger Lakes Community College, Gallery 1100 in Buffalo and Alfred University. By entering each of these three large paintings serially into different Rochester Finger Lakes exhibitions, he won the top prize three shows in a row. In 1995, the same triptych was the centerpiece of his contribution to a three-artist show along with William Stanley Taft, Jr. and Jerome Witkin. The show featured Witkin’s suite of paintings about Buchenwald alongside Insalaco’s work. In 1996, the triptych made its way into the New York State Biennial at the New York State Museum—participating museums included Albright-Knox, Brooklyn Museum, Memorial Art Gallery, Munson-Williams-Proctor, Queens Museum of Art, and College Art Gallery at SUNY New Paltz. Insalaco’s paintings were shown with work by a small selection of artists from around the state, including Joy Taylor, Stephen Assael, George Wexler, Elizabeth Olbert, and Phil Lonergan. His paintings have also been shown at Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse and the Butler Institute of Art in Ohio, which owns his work. After he retired from a 30-year career of teaching at SUNY/Finger Lakes Community College, the school named its art gallery after him, along with his fellow professor and close friend, sculptor Wayne Williams, who founded the school’s art program along with Insalaco in 1969.

Yet these honors have been rare, partly because Insalaco shuns the art world. He views it with irascible skepticism, casting a gimlet eye on much of what passes for visual art in the 21st century. He paints like an Old Master, without any required postmodern irony to make his antiquated methods feel contemporary. Once upon a time, he worked with great skill as a photo-realist in the wake of that movement’s emergence in the 70s. It was directly after this, in his middle period, as it were, that he constructed vivid visions of his own inner life, painstakingly detailed and realistic, both surreal and Baroque, a visual truce between the 20th and the 17th century. His Tribute Triptych, 104” x 248,” marked this leap forward in his work. At the time, these paintings drew the interest of both curators and critics across the state. Insalaco was poised to become far more widely known. But since then, he withdrew and continued to work mostly out of view. He still paints daily, by artificial light—all windows shuttered or curtained—chasing the glow of Rembrandt, Rubens, and Caravaggio, for the most part, still trying to make mysteries visible, but in a less epic way than in the past.

2

Insalaco isn’t a reactionary. He loves and admires much modern and contemporary art. He regularly books a room in Manhattan and tours both the museums and the galleries, sometimes putting in a week to absorb what he needs to see. In his own idiosyncratic way, he cherry-picks MORE

February 10th, 2018 by dave dorsey

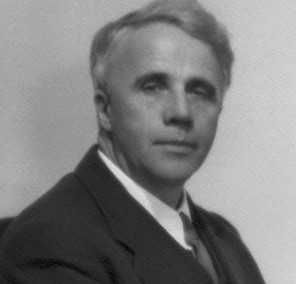

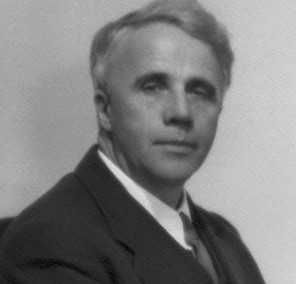

Robert Frost, 1874-1963

From the Robert Hughes documentary on Robert Frost, A Lover’s Quarrel with the World, filmed in the last year of Frost’s life, recently shown on PBS. He talks using the vocabulary of his poetry, the simplest and most elemental language, words as clear as a mountain creek in conversation, and they seem to be just as clear in the poems, though so often they withhold as much as they reveal. His lines are as inexhaustible as Emily Dickinson’s, plain-spoken but sometimes as tough to open up as a koan. The notion of withdrawal here is so resonant as well as the comparison of writing poetry to chopping down a tree or cutting grass–wresting order and form from the world. Hayden Cayruth, in a University of Rochester workshop I attended many years ago, spoke about how the act of writing generates an almost physical pleasure, and that wrestling with words for him actually seemed like a physical task. So much of painting is exactly that: an almost entirely physical, form-making engagement with the world that somehow generates meaning. Does anyone know how that happens? Frost always said he had no idea what a poem would say when he started, but as he worked on it, he followed the words where they led, like ice on a hot stove riding its own melting. The meaning arose from the act of making it, not the other way around.

From the documentary, a few of Frost’s thoughts on poetry, but they might as well be about painting:

Never do it to pay a bill. Because you probably won’t. It comes to market in the long run, but you can’t write it that way. The only self-conscious thought I ever have is “this seems to be going pretty good!” Another step, “still going!” It’s like skating on thin ice when you might go through. Once I’m going, I think it’s like starting a sled at the top of a hill and it goes hard to start but you get right over that gritty place and . . . she goes. We don’t escape. That’s a word I loathe. But retreat. You retreat for strength. You aren’t brought up in the right religion if you don’t know what retreat is. You withdraw . . . I’ve often said that every poem solves something for me in life. I go so far as to say that every poem is a momentary stay against the confusion of the world. But of course any psychiatrist will tell you making a basket or making a horseshoe or giving anything form gives you confidence in the universe, that it has form. When you talk about your troubles, you’re a fool. The best way to settle them is to make something that has form. All that makes you healthy and well is the feeling that there is some sort of poem to your business, your occupation. Two or three of my favorite things are a scythe, a hayfork and a fountain pen.